A Is for ASHTON to Paraphrase a Well-Known Saying

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring and Comparing Knowledge

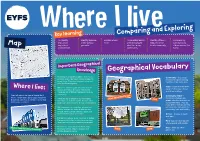

EYFS Where I live Key learning Comparing and Exploring To Identify Identify features Explain where Understand about Identify different Compare my features in in the school I live. different people features in the community to my school grounds. who live in our local community. others around the Map environment. community. world. Important Geographical Knowledge Geographical Vocabulary People in communities might go to the same Community - Is a group schools, shop in the same stores and do the of people living or working same things. They also help each other and together in the same area. solve problems together. Town - A place where there We live in different types of homes such as are a lot of houses, stores, Where I live: houses and flats in the same community. There are lots of different people living in our and other buildings. community. I can talk about the type of home that I Community helper - live in. I know that I go to Oasis Academy There are lots of people in our community Semi detached house Community helpers are Broadoak, which is in Ashton. I know that that helps us, such as nurses, doctors, vets, Flat people who live and work in Ashton is in England. policeman, shop keepers, fireman and teachers. our communities. They do many different things to help We have maps on computers, phones and us every day. They keep the tablets, and use the maps to find our way community safe and healthy. around. When you get used to a place, you remember the map in your head. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Strategic Commissioning Board, 16

Public Document Pack STRATEGIC COMMISSIONING BOARD Day: Wednesday Date: 16 December 2020 Time: 1.00 pm Place: Zoom Meeting Item AGENDA Page No. No 1 WELCOME AND APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST To receive any declarations of interest from Members of the Board. 3 MINUTES 3a MINUTES OF THE PREVIOUS MEETING 1 - 6 The Minutes of the meeting of the Strategic Commissioning Board held on 25 November 2020 to be signed by the Chair as a correct record. 3b MINUTES OF EXECUTIVE BOARD 7 - 32 To receive the Minutes of the Executive Board held on: 11 November 2020, 2 December 2020. 3c MINUTES OF THE LIVING WITH COVID BOARD 33 - 40 To receive the Minutes of the Living with Covid Board held on 4 November and 18 November 2020. 4 REVENUE MONITORING STATEMENT AT 31 OCTOBER 2020 41 - 54 To consider the attached report of the Executive Member, Finance and Economic Growth / CCG Chair / Director of Finance. 5 GM REPROCUREMENT OF AGE RELATED HEARING LOSS, HEAD AND 55 - 62 NECK MRI AND NON OBSTETRIC ULTRASOUND To consider the attached report of the Executive Member, Adult Social Care and Health / CCG Chair / Director of Commissioning. 6 MACMILLAN GP IN CANCER AND PALLIATIVE CARE WITH REVISED 63 - 78 JOB DESCRIPTION To consider the attached report of the Executive Member, Adult Social Care and Health / CCG Chair / Director of Commissioning. 7 ADULT SERVICES HOUSING AND ACCOMMODATION WITH SUPPORT 79 - 94 STRATEGY 2021-2026 From: Democratic Services Unit – any further information may be obtained from the reporting officer or from Carolyn Eaton, Principal Democratic Services Officer, to whom any apologies for absence should be notified. -

The Harridge Round Walk

Introducing Walk 12 Manchester’s Countryside The Harridge Round Walk Higher Swineshaw Reservoir 9 Views over to Buckton Castle hill, with its ancient ring fort on top, the working quarry next to it and Carrbrook Heritage Village open out below. In the distance, Hartshead Pike and other local landmarks also appear. 10 Spectacular views across Manchester and Cheshire open out as the track rounds the hillside and rejoins the Pennine Bridleway and rough track. Turn right to Duck Island follow it back down towards Carrbrook and the car park. For further visitor information on Tameside For more information on Countryside telephone: 0161 330 9613 Manchester's Countryside, including downloads of the walks, visit This walk forms part of a series of walks and www.manchesterscountryside.com trails developed by Manchester's Countryside. Telephone: 01942 825677; email: [email protected] Carrbrook – Walkerwood – Brushes – Swineshaw – Carrbrook 3 As you gain height along 5 The path circles the contours of the The Harridge 1 the Bridleway good views open hillside, with excellent views over Round Walk out over much of Stalybridge, Walkerwood Reservoir and the lower Distance: Mossley, Ashton and Greater Brushes Valley, before dropping down to Manchester. It’s worthwhile on join the tarmac reservoir service road. 5 miles/8km. 2 a clear day to explore the views Starting point: 6 Go left through the gate up the and try to identify distant Castle Clough Car Park, at the top of reservoir service road. As you continue up landmarks such as Beetham Buckton Vale Road, Carrbrook, Stalybridge. the road, mature oak wood, fields and Tower, Manchester and Grid ref. -

Bulletin Vol 43 No2 Summer 2013 Col.Pub

Saddleworth Historical Society Bulletin Volume 43 Number 2 Summer 2013 Bulletin of the Saddleworth Historical Society Volume 43 Number 2 Summer 2013 The Mallalieus of Windybank, Ashton-Under-Lyne, Lancashire 27 Anne Clark More About Dacres Hall In Greenfield 37 Jill Read Early Days of Co-operation in Denshaw 49 Mike Buckley Cover Illustration: Engraving of Dacres prepared as an advertisement. [Saddleworth Historical Society Archives H/How/99] ©2013 Saddleworth Historical Society and individual contributors i ii SHS Bulletin Vol. 43 No. 2 Summer 2013 THE MALLALIEUS OF WINDYBANK, ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE, LANCASHIRE. Anne Clark1 Francis Mayall Mallalieu [Family collection] A faded framed photograph (above) of a stately looking gentleman with white hair always hung on the wall of my late father’s bedroom. This was ‘Great Uncle Frank’; who was my paternal grandmother’s great uncle and his surname was Mallalieu. The stories passed down through the family were that he had been a Superintendent in the Metropolitan Police Force in London, that he had set up the Police Force in Barbados and that he had married an illegitimate daughter of George IV. ‘Great Uncle Frank’ was in fact Francis Mayall Mallalieu and it has been discovered that there were six of that name over four generations. 1 I would like to thank the people who have helped with this research over many years, in particular Mike Buckley, Linda Cooper and Steve Powell. 27 SHS Bulletin Vol. 43 No. 2 Summer 2013 Francis Mayall Mallalieu 1 The first Francis Mayall Mallalieu (FMM1) was baptised on 31st August 1766 at St. -

Agenda Template

STRATEGIC PLANNING AND CAPITAL MONITORING PANEL 21 September 2020 Commenced: 2.00 pm Terminated: 2.56 pm Present: Councillors Warrington (Chair), Cooney, Fairfoull, McNally, Newton, Reid, Ryan and Dickinson In Attendance: Sandra Stewart Director of Governance and Pensions Kathy Roe Director of Finance Ian Saxon Director - Operations and Neighbourhoods Jayne Traverse Director of Growth Tom Wilkinson Assistant Director of Finance Emma Varnam Assistant Director - Stronger Communities Tim Bowman Assistant Director for Education Sandra Whitehead Assistant Director Adults Debbie Watson Assistant Director of Population Health Mark Steed Capital Projects Consultant Apologies for Absence: Councillor Feeley 11 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest. 12 MINUTES The minutes of the meeting of the Strategic Planning and Capital Monitoring Panel on the 6 July 2020 were approved as a correct record with the amendment that Councillor Dickinson removed as present and be recorded as submitting apologies. 13 ADULTS CAPITAL MONITORING Consideration was given to a report of the Executive Member (Adult Social Care and Health)/Director of Adult Services which provided an update on the Adults Capital Programme which now included three schemes that were being funded from the Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) as well as the two schemes previously reported on. Progress on these schemes was reported alongside the main DFG within the Growth Directorate Capital update report. The five projects contained within the report were: 1. The review of the day time offer 2. Christ Church Community Developments (CCCD) - 4C Community Centre in Ashton 3. Moving with Dignity (Single Handed Care) 4. Disability Assessment Centre 5. Brain in Hand The Oxford Park business case report and the Christ Church Community Developments (CCCD) 4C Community Centre in Ashton reports had previously been agreed by Members. -

APH News Spring 2013

April 2013 PIONEER NEWS Spring 2013 People making the news in the St. Peter’s area of Ashton-u-Lyne WIN £25 Internet drop-in sessions COMPLETE ENCLOSED QUESTIONNAIRE ON OUR REPAIR SERVICE at the tenants base SEE PAGE 13 FOR MORE DETAILS APH and REACH have worked together and installed internet access in the Tenants Base! Residents can call in on Tuesday afternoons between 1pm and 3pm for free access to the computers. Residents can use the internet to search for a job, help with benefits and housing benefit claims. We have also introduced “One To One” sessions where residents can spend time learning basic I.T skills. Residents will get help setting up email accounts and Facebook pages supported by local volunteers and staff from Ashton Pioneer Homes.We are also going to host a session on Social Media for Beginners. You may be aware that Ashton Pioneer Homes and Pioneer People have two Facebook pages, and residents are encouraged to “like” these pages. We use these pages to share information about Welfare Reform and other relevant topics. We also give regular updates on the Community Groups and what the Resident Involvement Team has been up to. If you would like to find out more or book a session please contact Nicola on 0161 343 8128 or call in to the office. UNIVERSAL CREDIT IS COMING TO TAMESIDE THIS MONTH Did you know? Universal Credit is a new type of financial support for people of working age who are looking for Universal Credit will be a work or on a low income. -

Report To: Strategic Planning and Capital Monitoring Panel Date: 14 September 2020 Executive Member: Councillor Oliver Ryan

Report to: Strategic Planning and Capital Monitoring Panel Date: 14 September 2020 Executive Member: Councillor Oliver Ryan - Executive Member (Finance and Economic Growth). Reporting Officer: Jayne Traverse, Director of Growth Subject: GROWTH UPDATE REPORT Report Summary: This report provides an update, on the 2020/21 Growth Capital Programme and sets out details of the major approved capital schemes in this Directorate. Recommendations: That Members note the report and recommend to Executive Cabinet that the following be added to the approved Council Capital Programme Statutory Compliance expenditure of £143,353 which was urgent and unavoidable and scheduled at Appendix 2 including £7,000 additional required spend on Hartshead Pike as set out in the report. Corporate Plan: The schemes set out in this report supports the objectives of the Corporate Plan. Policy Implications: In line with procurement and financial policy framework. Draft Financial Implications: Corporate Landlord – Capital Expenditure (Authorised by the statutory The Capital Programme includes an earmarked resource of Section 151 Officer & Chief £0.728m for Property Assets Statutory Compliance works. Works Finance Officer) to date in previous years have been reported to the Strategic Capital Panel retrospectively as completed. This report is requesting a further £143,353, as scheduled in Appendix 2, which includes £7,000 additional required spend on Hartshead Pike, from the above earmarked budget. If approved the remaining earmarked budget for Property Assets Statutory Compliance works would be £0.585m. Continued work being undertaken by the Council, in regard to emergency repairs to Hartshead Pike has identified the requirement to undertake further work in regard to structural repair investigations. -

Take a Walk in One of Our Parks

#ProudTameside ISSUE 83 I SPRING 2020 DISTRIBUTED FREE TO OVER 100,000 HOMES AND BUSINESSES IN TAMESIDE Vision Tameside Free Food Vouchers for What’s On IN THIS ISSUE: P4/5 families on low income P19 P22 Take a walk in one of our parks FOLLOW US ON AND SPRING 2020 I THE TAMESIDE CITIZEN I PAGE 2 TAMESIDE COMMUNITY RESPONSE SERVICE Need help? Just press! You press the button. 1 Response 4 2 Our operator arranged answers your appropriate call and speaks to your needs. CRS to you through the unit. 3 Emergency home responder sent to your home. Emergency Response 24 hours a day 365 days a year Supporting you to live independently 0161 342 5100 tameside.gov.uk/CRS SPRING 2020 I THE TAMESIDE CITIZEN I PAGE 3 Welcome to the spring edition of the Tameside Citizen Spring is a season of new beginnings and optimism and there’s certainly a huge amount of positive change that’s taking place in Tameside. This issue is packed with details of developments that are now coming to fruition and will benefit all of us. Tameside Wellness Centre – Denton is now open with residents able to use a host of leisure, wellbeing and community facilities; Contents Ashton Interchange will open soon and Vision Tameside is continuing to bring improvements to Ashton Town Centre. But it’s not all about the new Vision Tameside........................4&5 – there’s also much work to protect Tameside’s heritage, from restoring Ashton Town Hall to repairing Mossley’s Hartshead Pike. Cycling & Walking.....................6&7 With warmer weather on the way there are also lots of events and activities Budget Conversation....................8 to inspire people to get outdoors and enjoy Tameside’s picturesque scenery and wonderful town centres. -

Excavations at Buckton Castle, Tameside, Greater Manchester. a Report on the Archaeological Excavations Undertaken by the University of Manchester in 2008

Excavations at Buckton Castle, Tameside, Greater Manchester. A Report on the Archaeological Excavations Undertaken by the University of Manchester in 2008 A Report by Brian Grimsditch and Dr Michael Nevell CfAA Report No: 1/2009 Centre for Applied Archaeology School of the Built Environment CUBE University of Salford 113-115 Portland Street Manchester M1 6DW Tel: 0161 295 3818 Email: [email protected] Web: www.cfaa.co.uk © CfAA. Hill Farm Barn, Staffordshire, Historic Building Survey, May 2011 1 Contents Summary 3 1. Introduction 6 2. Archaeological and Historical Background 8 3. Methodology 23 4. Results 27 5. Discussion 35 6. Specialist Report: The Artefactual Evidence by Ruth Garratt 39 7. Conclusion 55 8. Sources 59 10. Acknowledgements 64 Appendix 1: Photographic catalogue 65 Appendix 2: Summary List of Contexts 79 Appendix 3: Excavation Archive 84 Appendix 4: Assemblage Archive 85 Plates (Illustrations) 92 Plates (Photos) 104 ©Centre for Applied Archaeology, University of Salford. Buckton Castle Excavation Report for 2008 2 Summary This report summarises the results of fieldwork at Buckton Castle, a Scheduled Ancient Monument in Tameside, Greater Manchester (SD 9892 0162; NMR 27598; GMSMR 56), carried out during March and April 2008 by the University of Manchester Archaeological Unit. The work was funded by the Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council and Scheduled Ancient Monument Consent to excavate was obtained from English Heritage. The project brief/remit of archaeological works was designed, in consultation with the County Archaeologist Norman Redhead at the Greater Manchester Archaeology Unit, with the aim of gaining a better understanding of the monument; attempting to assess its date of construction, and to place it in context within the region and with other similar monuments. -

Upper Mossley Trail

Mossley Civic Society Local Interest Trail No. 1 Upper Mossley Mossley Civic Society 1981, revised 2018. START at the George Lawton Hall, Stamford Street. The name of the Fleece Inn on the right is a reminder of the woollen trade carried on in the town before The life-sized sculpture of a woman, dressed as a cotton spinning became the major industry. Other traditional mill girl with baskets of bobbins, stands similar local inn names were The Pack Horse and outside George Lawton Hall, the site of the original The Shears Inn. Albion Mill. Mill girls formed the backbone of the industry and represent the towns textile heritage. Continue the walk by going up the road towards Ashton, keeping to the footpath on the left hand side. Walk up Stamford Street, past the bus shelters and market ground. The fire station on the left was the site of the Bull‘s Head, which was a stopping place for the stagecoach The market ground at the beginning of the 20th which ran from Huddersfield to Manchester. century was a centre of entertainment. Travelling Unfortunately, the Bull’s Head got into a poor state of theatres used to play in tents set up on the market repair and had to be demolished a few years ago. ground, presenting everything from “Maria Martin” and “Nobody’s Child” to “Hamlet” and “Lady Audley’s Across Stamford Street was the pawn shop. lt was will see what appears to be a tall, narrow stone wall. Secret”. the centre of great activity on Saturday afternoon This is a memorial to a soldier, John Whitworth, when the Sunday suit would be redeemed, to be On market day - Friday afternoons - lit by paraffin who was born in Mossley in 1782 and died in 1848. -

University and Professional Courses

Tameside College University and Professional Courses 2021/22 James Raisbeck: HNC in Electrical Engineering “Being able to learn in an environment with good facilities and having learning aids readily available really helped me in my studies.” Natalie Jayne Hobin: Level 5 Certificate in Human Resource Management (CIPD) “The sense of achievement I got every time I handed in my assignment and got that pass mark was all worth it after not studying for over 22 years. I am glad I have done it!” Brad Gee: HND in Computing and Systems Development “I loved studying at Tameside College. I expanded my knowledge of IT, and loved how calm the learning environment was. My teachers were really approachable.” David Smith: Certificate of Education “The highlight for me is that Tameside College has so much to offer in regards to providing further education to meet everyone’s needs for the areas they wish to develop and explore.” 2 www.tameside.ac.uk How to apply UCAS / Direct Applications / Loan Information You can apply to Tameside College by visiting www.ucas.com and searching for Tameside College in the search engine. The UCAS deadline for Most of the university Undergraduate courses courses are payable via is Tuesday 15th January either Advanced Learner 2021. The reference must Loans (Access to HE / be completed before the Professional Courses) or application can be sent to Higher Education loans – us. For courses starting in more information can be 2021, the application fee is found at https://www.gov. £20 for a single choice. uk/student-finance If applying via UCAS, please check regularly for updates on your application; alternatively we also accept direct applications via our website: www.tameside.ac.uk Apply online: www.tameside.ac.uk/on 3 National Student Survey The latest published NSS survey (2018) shows an 87% overall satisfaction rate, compared to a national benchmark of 83%. -

June 2020 - Local Business & Community News - Shopping & What’S on Guide

: abouttameside : @abouttameside : [email protected] TAMESIDE Scan to visit our website: June 2020 - Local Business & Community News - Shopping & What’s On guide MEET DROYLSDEN’S STAR FAN STEFAN - SEE PAGE 8 : THE GRAFTON CENTRE - WILLOW WOOD - MARKET NEWS INSIDE About Tameside 1 Read online at: www.tamesidemag.com or pick up your FREE copy from Ladysmith Shopping Centre Ashton, Tameside Markets, Cineworld Ashton, Vaughan & Lester Denton, Clarendon Square Shopping Centre Hyde, Ian McConnell Vets Mossley, Stalybridge Train station. Tameside Libraries and many more locations. Welcome... Highlights this issue... Pick up a copy from: Aldi supermarkets, Ashton ROTARY DONATION ………………………… 4 Market Hall, Stalybridge Train Station, Droylsden DROYLSDEN’S STAR FAN …………………… 8 Post Office, Ladysmith Shopping Centre and more! STUDENT SUPPORT …………………………10 TAMESIDE TAXIS NHS FUND ………………15 AFTER THE VE DAY SPECIAL …………………………16 - 18 ABOUT HYDE …………………………………20 THE GRAFTON CENTRE ……………………21 LOCKDOWN HERITAGE ………………………………………25 EASES, SUPPORT QUIZ SPECIAL ………………………… 26 & 27 Deadline for our July issue is June 21st. YOUR LOCAL Email: [email protected] Read us online: www.tamesidemag.com BUSINESSES and join us on Facebook! Email: Telephone: Contributors this issue [email protected] 0774 3174244 Howard Murphy - Jill Morris - Tameside Markets - Jan Lord - Tameside College - Local Studies Library - Andy Production Design Richardson - TMBC - Ladysmith Shopping Centre - Inflict Design - [email protected] Bromleys Solicitors - Peter Harrington - Active Tameside - Val Unwin - Deborah Turner - Stefan Dean - Luke Mirfin Ask about our cost effective advertising - Emmaus - Willow Wood Hospice - The Grafton Centre - opportunities and special features in the magazine. Email [email protected] Councillor Philip Fitzpatrick - Councillor Jacqueline Owen - Laura Kelly - Wendy Brookes - Sam Shaw Advertising terms and conditions available on request.