PE = Mgh What Is G Here?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Difference Between BTU and Watts Key Difference - BTU Vs Watts

Difference Between BTU and Watts www.differencebetween.com Key Difference - BTU vs Watts It is first important to identify the concepts of energy and power in order to understand the difference between BTU and Watts. If an object is doing a work, the object is given an amount of energy to perform the task. If there is a heat transfer from or to an object, an amount of energy is removed from or given to the said object. The rate of work done or the rate of the heat transfer is defined as power. BTU and Watt are two different types of measurement units to measure the energy transfer and power, respectively. Thus, the key difference between BTU and Watts is that BTU measures energy, which is a stand-alone physical property whereas Watts measures the rate of transfer of energy that is always associated with a time factor. What is BTU? BTU is the abbreviated form for British Thermal Unit. The term thermal is often used for measuring thermal energy or the energy in the form of heat. BTU is not a part of the International System of Units or SI units. But it is often used as a measurement in heating and air-conditioning industry even at present. One BTU is defined as the amount of heat that should be transferred to one pound (lb) of water to raise its temperature by one degree of Fahrenheit (F). Since lb and F are both conventional units, the BTU can be identified by its SI units’ counterpart, Joule (J). That is, one joule is the heat required to transfer to one gram of water to raise the temperature by one degree Celsius (C). -

Natural Gas, 22.6

Syllabus Section I Power Market Restructuring: Current Context and Historical Events ** Important Acknowledgement: These notes are an edited abridged version of a set of on-line lecture notes prepared by Professor Tom Overbye, ECpE, University of Illinois, 2008 Last Revised: 9/13/2011 Setting Course Topics in Context EE/Econ 458 focuses on the restructuring of wholesale power markets, using the U.S. as the primary source of illustrations. Particular attention will be focused on U.S. restructuring efforts in the Midwest (MISO), New England (ISO-NE), New York (NYISO), mid- Atlantic States (PJM), California (CAISO), Texas (ERCOT), and the Southwest Power Pool (SPP). First, however, it is important to consider this restructuring movement within the larger context of the energy delivery system as a whole. Electric Systems in Energy Context Electricity is used primarily as a means for energy transportation. – Other sources of energy are used to create it, and once created it is usually converted into other forms of energy before actual use. About 40% of US energy is transported in electric form. Concerns about CO2 emissions and the depletion of fossil fuels are becoming main drivers for change in the world energy infrastructure. Measurement of Power Power: Instantaneous consumption of energy Power Units Watts (W) = voltage times current for DC systems kW – 1 x 103 Watts MW – 1 x 106 Watts GW – 1 x 109 Watts Installed U.S. generation capacity is about 900 GW ( about 3 kW per person) Measurement of Energy Energy: Integration of power over time; energy is what people really want from a power system Energy Units: Joule = 1 Watt-second (J) kWh – Kilowatt-hour (3.6 x 106 J) Btu – 1054.85 J (British Thermal Unit) Note on Unit Conversion: 3413 Btu ≈ 1 kWh Annual U.S. -

AST242 LECTURE NOTES PART 3 Contents 1. Viscous Flows 2 1.1. the Velocity Gradient Tensor 2 1.2. Viscous Stress Tensor 3 1.3. Na

AST242 LECTURE NOTES PART 3 Contents 1. Viscous flows 2 1.1. The velocity gradient tensor 2 1.2. Viscous stress tensor 3 1.3. Navier Stokes equation { diffusion 5 1.4. Viscosity to order of magnitude 6 1.5. Example using the viscous stress tensor: The force on a moving plate 6 1.6. Example using the Navier Stokes equation { Poiseuille flow or Flow in a capillary 7 1.7. Viscous Energy Dissipation 8 2. The Accretion disk 10 2.1. Accretion to order of magnitude 14 2.2. Hydrostatic equilibrium for an accretion disk 15 2.3. Shakura and Sunyaev's α-disk 17 2.4. Reynolds Number 17 2.5. Circumstellar disk heated by stellar radiation 18 2.6. Viscous Energy Dissipation 20 2.7. Accretion Luminosity 21 3. Vorticity and Rotation 24 3.1. Helmholtz Equation 25 3.2. Rate of Change of a vector element that is moving with the fluid 26 3.3. Kelvin Circulation Theorem 28 3.4. Vortex lines and vortex tubes 30 3.5. Vortex stretching and angular momentum 32 3.6. Bernoulli's constant in a wake 33 3.7. Diffusion of vorticity 34 3.8. Potential Flow and d'Alembert's paradox 34 3.9. Burger's vortex 36 4. Rotating Flows 38 4.1. Coriolis Force 38 4.2. Rossby and Ekman numbers 39 4.3. Geostrophic flows and the Taylor Proudman theorem 39 4.4. Two dimensional flows on the surface of a planet 41 1 2 AST242 LECTURE NOTES PART 3 4.5. Thermal winds? 42 5. -

Energy Literacy Essential Principles and Fundamental Concepts for Energy Education

Energy Literacy Essential Principles and Fundamental Concepts for Energy Education A Framework for Energy Education for Learners of All Ages About This Guide Energy Literacy: Essential Principles and Intended use of this document as a guide includes, Fundamental Concepts for Energy Education but is not limited to, formal and informal energy presents energy concepts that, if understood and education, standards development, curriculum applied, will help individuals and communities design, assessment development, make informed energy decisions. and educator trainings. Energy is an inherently interdisciplinary topic. Development of this guide began at a workshop Concepts fundamental to understanding energy sponsored by the Department of Energy (DOE) arise in nearly all, if not all, academic disciplines. and the American Association for the Advancement This guide is intended to be used across of Science (AAAS) in the fall of 2010. Multiple disciplines. Both an integrated and systems-based federal agencies, non-governmental organizations, approach to understanding energy are strongly and numerous individuals contributed to the encouraged. development through an extensive review and comment process. Discussion and information Energy Literacy: Essential Principles and gathered at AAAS, WestEd, and DOE-sponsored Fundamental Concepts for Energy Education Energy Literacy workshops in the spring of 2011 identifies seven Essential Principles and a set of contributed substantially to the refinement of Fundamental Concepts to support each principle. the guide. This guide does not seek to identify all areas of energy understanding, but rather to focus on those To download this guide and related documents, that are essential for all citizens. The Fundamental visit www.globalchange.gov. Concepts have been drawn, in part, from existing education standards and benchmarks. -

Toolkit 1: Energy Units and Fundamentals of Quantitative Analysis

Energy & Society Energy Units and Fundamentals Toolkit 1: Energy Units and Fundamentals of Quantitative Analysis 1 Energy & Society Energy Units and Fundamentals Table of Contents 1. Key Concepts: Force, Work, Energy & Power 3 2. Orders of Magnitude & Scientific Notation 6 2.1. Orders of Magnitude 6 2.2. Scientific Notation 7 2.3. Rules for Calculations 7 2.3.1. Multiplication 8 2.3.2. Division 8 2.3.3. Exponentiation 8 2.3.4. Square Root 8 2.3.5. Addition & Subtraction 9 3. Linear versus Exponential Growth 10 3.1. Linear Growth 10 3.2. Exponential Growth 11 4. Uncertainty & Significant Figures 14 4.1. Uncertainty 14 4.2. Significant Figures 15 4.3. Exact Numbers 15 4.4. Identifying Significant Figures 16 4.5. Rules for Calculations 17 4.5.1. Addition & Subtraction 17 4.5.2. Multiplication, Division & Exponentiation 18 5. Unit Analysis 19 5.1. Commonly Used Energy & Non-energy Units 20 5.2. Form & Function 21 6. Sample Problems 22 6.1. Scientific Notation 22 6.2. Linear & Exponential Growth 22 6.3. Significant Figures 23 6.4. Unit Conversions 23 7. Answers to Sample Problems 24 7.1. Scientific Notation 24 7.2. Linear & Exponential Growth 24 7.3. Significant Figures 24 7.4. Unit Conversions 26 8. References 27 2 Energy & Society Energy Units and Fundamentals 1. KEY CONCEPTS: FORCE, WORK, ENERGY & POWER Among the most important fundamentals to be mastered when studying energy pertain to the differences and inter-relationships among four concepts: force, work, energy, and power. Each of these terms has a technical meaning in addition to popular or colloquial meanings. -

Energetics of a Turbulent Ocean

Energetics of a Turbulent Ocean Raffaele Ferrari January 12, 2009 1 Energetics of a Turbulent Ocean One of the earliest theoretical investigations of ocean circulation was by Count Rumford. He proposed that the meridional overturning circulation was driven by temperature gradients. The ocean cools at the poles and is heated in the tropics, so Rumford speculated that large scale convection was responsible for the ocean currents. This idea was the precursor of the thermohaline circulation, which postulates that the evaporation of water and the subsequent increase in salinity also helps drive the circulation. These theories compare the oceans to a heat engine whose energy is derived from solar radiation through some convective process. In the 1800s James Croll noted that the currents in the Atlantic ocean had a tendency to be in the same direction as the prevailing winds. For example the trade winds blow westward across the mid-Atlantic and drive the Gulf Stream. Croll believed that the surface winds were responsible for mechanically driving the ocean currents, in contrast to convection. Although both Croll and Rumford used simple theories of fluid dynamics to develop their ideas, important qualitative features of their work are present in modern theories of ocean circulation. Modern physical oceanography has developed a far more sophisticated picture of the physics of ocean circulation, and modern theories include the effects of phenomena on a wide range of length scales. Scientists are interested in understanding the forces governing the ocean circulation, and one way to do this is to derive energy constraints on the differ- ent processes in the ocean. -

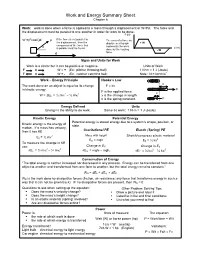

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

Innovation Insights Brief | 2020

FIVE STEPS TO ENERGY STORAGE Innovation Insights Brief | 2020 In collaboration with the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) ABOUT THE WORLD ENERGY COUNCIL ABOUT THIS INSIGHTS BRIEF The World Energy Council is the principal impartial This Innovation Insights brief on energy storage is part network of energy leaders and practitioners promoting of a series of publications by the World Energy Council an affordable, stable and environmentally sensitive focused on Innovation. In a fast-paced era of disruptive energy system for the greatest benefit of all. changes, this brief aims at facilitating strategic sharing of knowledge between the Council’s members and the Formed in 1923, the Council is the premiere global other energy stakeholders and policy shapers. energy body, representing the entire energy spectrum, with over 3,000 member organisations in over 90 countries, drawn from governments, private and state corporations, academia, NGOs and energy stakeholders. We inform global, regional and national energy strategies by hosting high-level events including the World Energy Congress and publishing authoritative studies, and work through our extensive member network to facilitate the world’s energy policy dialogue. Further details at www.worldenergy.org and @WECouncil Published by the World Energy Council 2020 Copyright © 2020 World Energy Council. All rights reserved. All or part of this publication may be used or reproduced as long as the following citation is included on each copy or transmission: ‘Used by permission of the World -

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions 3.1 The Important Stuff 3.1.1 Position In three dimensions, the location of a particle is specified by its location vector, r: r = xi + yj + zk (3.1) If during a time interval ∆t the position vector of the particle changes from r1 to r2, the displacement ∆r for that time interval is ∆r = r1 − r2 (3.2) = (x2 − x1)i +(y2 − y1)j +(z2 − z1)k (3.3) 3.1.2 Velocity If a particle moves through a displacement ∆r in a time interval ∆t then its average velocity for that interval is ∆r ∆x ∆y ∆z v = = i + j + k (3.4) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t As before, a more interesting quantity is the instantaneous velocity v, which is the limit of the average velocity when we shrink the time interval ∆t to zero. It is the time derivative of the position vector r: dr v = (3.5) dt d = (xi + yj + zk) (3.6) dt dx dy dz = i + j + k (3.7) dt dt dt can be written: v = vxi + vyj + vzk (3.8) 51 52 CHAPTER 3. MOTION IN TWO AND THREE DIMENSIONS where dx dy dz v = v = v = (3.9) x dt y dt z dt The instantaneous velocity v of a particle is always tangent to the path of the particle. 3.1.3 Acceleration If a particle’s velocity changes by ∆v in a time period ∆t, the average acceleration a for that period is ∆v ∆v ∆v ∆v a = = x i + y j + z k (3.10) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t but a much more interesting quantity is the result of shrinking the period ∆t to zero, which gives us the instantaneous acceleration, a. -

Hydroelectric Power -- What Is It? It=S a Form of Energy … a Renewable Resource

INTRODUCTION Hydroelectric Power -- what is it? It=s a form of energy … a renewable resource. Hydropower provides about 96 percent of the renewable energy in the United States. Other renewable resources include geothermal, wave power, tidal power, wind power, and solar power. Hydroelectric powerplants do not use up resources to create electricity nor do they pollute the air, land, or water, as other powerplants may. Hydroelectric power has played an important part in the development of this Nation's electric power industry. Both small and large hydroelectric power developments were instrumental in the early expansion of the electric power industry. Hydroelectric power comes from flowing water … winter and spring runoff from mountain streams and clear lakes. Water, when it is falling by the force of gravity, can be used to turn turbines and generators that produce electricity. Hydroelectric power is important to our Nation. Growing populations and modern technologies require vast amounts of electricity for creating, building, and expanding. In the 1920's, hydroelectric plants supplied as much as 40 percent of the electric energy produced. Although the amount of energy produced by this means has steadily increased, the amount produced by other types of powerplants has increased at a faster rate and hydroelectric power presently supplies about 10 percent of the electrical generating capacity of the United States. Hydropower is an essential contributor in the national power grid because of its ability to respond quickly to rapidly varying loads or system disturbances, which base load plants with steam systems powered by combustion or nuclear processes cannot accommodate. Reclamation=s 58 powerplants throughout the Western United States produce an average of 42 billion kWh (kilowatt-hours) per year, enough to meet the residential needs of more than 14 million people. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

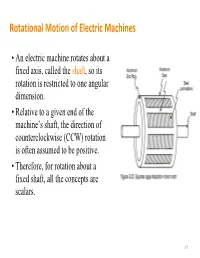

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines • An electric machine rotates about a fixed axis, called the shaft, so its rotation is restricted to one angular dimension. • Relative to a given end of the machine’s shaft, the direction of counterclockwise (CCW) rotation is often assumed to be positive. • Therefore, for rotation about a fixed shaft, all the concepts are scalars. 17 Angular Position, Velocity and Acceleration • Angular position – The angle at which an object is oriented, measured from some arbitrary reference point – Unit: rad or deg – Analogy of the linear concept • Angular acceleration =d/dt of distance along a line. – The rate of change in angular • Angular velocity =d/dt velocity with respect to time – The rate of change in angular – Unit: rad/s2 position with respect to time • and >0 if the rotation is CCW – Unit: rad/s or r/min (revolutions • >0 if the absolute angular per minute or rpm for short) velocity is increasing in the CCW – Analogy of the concept of direction or decreasing in the velocity on a straight line. CW direction 18 Moment of Inertia (or Inertia) • Inertia depends on the mass and shape of the object (unit: kgm2) • A complex shape can be broken up into 2 or more of simple shapes Definition Two useful formulas mL2 m J J() RRRR22 12 3 1212 m 22 JRR()12 2 19 Torque and Change in Speed • Torque is equal to the product of the force and the perpendicular distance between the axis of rotation and the point of application of the force. T=Fr (Nm) T=0 T T=Fr • Newton’s Law of Rotation: Describes the relationship between the total torque applied to an object and its resulting angular acceleration.