Witness Tree: What a Single, 100-Year-Old Oak Tells Us About Climate Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

2014 THREDBO BLUES FESTIVAL ARTIST LINE up Wendy Matthews an Australian Adult Alternative Pop Singer Originally from Canada

2014 THREDBO BLUES FESTIVAL ARTIST LINE UP Wendy Matthews an Australian adult alternative pop singer originally from Canada who has been a member of Models and Absent Friends and is a solo artist. She released Top 20 hit singles in the 1990s including "Token Angels", "Let's Kiss (Like Angels Do)", "The Day You Went Away" and "Friday's Child" with Top 20 albums, You've Always Got the Blues (duet album with Kate Ceberano), Émigre, Lily, The Witness Tree and her compilation, Stepping Stones. She has won six Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) Awards. According to rock music historian, Ian McFarlane she provides "extraordinary, crystal-clear vocals Jeff Lang Australian songwriter, singer and slide guitarist. A leading performer in the Australian roots music scene and purveyer of his self-described "disturbed folk" style, which incorporates primarily folk, blues and rock. Rick Price Rick Price is an Australian singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist and Music Producer Price began writing his own material in the late 80s, and released his debut single "Not A Day Goes By" in February 1992. The song received saturation radio and video play, climbing to number 5 on the national charts where it spent 20 weeks in the Australian Top 100.[citation needed] It was the beginning of a lifelong ambition for Price, and in the space of less than 12 months, he went from relative obscurity to become one of the biggest names in Australian music. Kevin Borich Kevin has played and recorded with artists such as Renee' Geyer `Blues License' - Dutch Tilders `The Blues Had a Baby '- Richard Clapton `Prushan Blue', Joe Walsh and The Party Boys, of which Kevin was a founding member. -

The Terra Verde Conservation Project

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1954 An Experiment in Teaching Convervation: The Terra Verde Conservation Project Russell James Bay The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Bay, Russell James, "An Experiment in Teaching Convervation: The Terra Verde Conservation Project" (1954). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9279. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9279 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN EXPERIMENT IN TEACHING- CONSERVATION: THE TERRA VERDE CONSERVATION PROJECT by RUSSELL BAY B. E. Montana State Normal College, 1938 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1954 Approved by: 1 Dean, duat(e School (3 ( f>rV ;— — r- UMI Number: EP72587 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP72587 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Catch Great Music

That’s what the Blues is about Australian Blues musician. After more than 10 Jungal — Jungal are three powerful young women who create their own indie years Ray is still very young for his considerable talent was noticed in the early root-rock music. Their energetic live performance and powerful 60s-like rock feel part of this century performing a 3 month residency with the house band in comes to life through three harmonious voices creating the unique and powerful B.B King’s Club in Memphis and Buddy Guy’s Blues Club in Chicago as well as ‘Jungal sound’, setting these girls apart from other female acts of their kind. several Southern Blues Festivals in the US of A. While in the states Ray recorded with Mark Sallings and has also had the privilege of performing with American A winner of six Australian Recording Industry Association Wendy Matthews — greats such as Andy Just, Dave Bowen and Chris Cain. Ali Penney & The Money Makers — Rawness and emotion are what strike you (ARIA) Awards Wendy is an acclaimed Australian adult alternative singer with when you hear what Ali Penney and The Money Makers play for you. Penney’s “extraordinary, crystal-clear vocals. Originally from Canada she has been a Mighty Reapers — The Mighty Reapers were formed by Robert Susz in 1988 husky, soulful voice is matched perfectly by the smooth sounds of the Money member of Models and Absent Friends and is a solo artist. She released a after the split of the Dynamic Hepnotics, one of the most successful soul/blues/ Makers’ blues. -

Wildland Fire in the Appalachians: Discussions Among Managers and Scientists

United States Department of Agriculture PROCEEDINGS Wildland Fire in the Appalachians: Discussions Among Managers and Scientists Forest Service Research & Development, Southern Research Station General Technical Report SRS-199, September 2014 Cover: Fire researchers monitor fire behavior and weather during a stand replacement fire for Table Mountain pine, Chattahoochee National Forest, Chattooga Ranger District. Disclaimers: Reference herein to any specific commercial products, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, and shall not be used for any endorsement purposes. Papers published in these proceedings were submitted by authors in electronic media. Editing was done to ensure consistent format. Authors are responsible for content and accuracy of their individual papers. Sepember 2014 Southern Research Station 200 W.T. Weaver Blvd. Asheville, NC 28804 www.srs.fs.usda.gov PROCEEDINGS Wildland Fire in the Appalachians: Discussions Among Managers and Scientists Edited by Thomas A. Waldrop Roanoke, Virginia October 8-10, 2013 Hosted by Consortium of Appalachian Fire Managers and Scientists Association for Fire Ecology Sponsored by Association for Fire Ecology Consortium of Appalachian Fire Managers and Scientists Joint Fire Science Program The Nature Conservancy Natural -

Northeast Temperate Network Long-Term Forest Monitoring Protocol 2016 Revision

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Northeast Temperate Network Long-term Forest Monitoring Protocol 2016 Revision Natural Resource Report NPS/NETN/NRR—2016/1184 ON THE COVER Camilla Seirup and Mary Short sampling a forest plot in Acadia National Park Photograph by: Kate Miller, NPS Northeast Temperate Network Long-term Forest Monitoring Protocol 2016 Revision Natural Resource Report NPS/NETN/NRR—2016/1184 Geri Tierney1, Brian Mitchell2, Kate Miller3, James Comiskey4, Adam Kozlowski2, Don Faber- Langendoen5 1Department of Environmental & Forest Biology SUNY College of Environmental Science & Forestry Syracuse, NY 13210 2Northeast Temperate Network 54 Elm Street Woodstock, VT 05091 3Northeast Temperate Network Acadia National Park Bar Harbor, ME 04609 4Mid-Atlantic Network 120 Chatham Lane Fredericksburg, VA 22405 5NatureServe Conservation Science Division Arlington, VA 22209 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. -

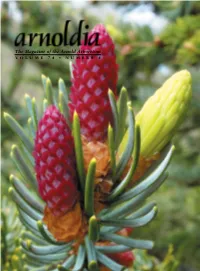

Open As a Single Document

The Magazine of the Arnold Arboretum VOLUME 74 • NUMBER 4 The Magazine of the Arnold Arboretum VOLUME 74 • NUMBER 4 • 2017 CONTENTS Arnoldia (ISSN 0004–2633; USPS 866–100) 2 The Wardian Case: How a Simple Box is published quarterly by the Arnold Arboretum Moved the Plant Kingdom of Harvard University. Periodicals postage paid Luke Keogh at Boston, Massachusetts. Subscriptions are $20.00 per calendar year 14 2016 Weather Summary domestic, $25.00 foreign, payable in advance. Sue A. Pfeiffer Remittances may be made in U.S. dollars, by check drawn on a U.S. bank; by international 23 Witness Tree: What a Single, 100-Year-Old money order; or by Visa, Mastercard, or American Oak Tells Us About Climate Change Express. Send orders, remittances, requests to purchase back issues, change-of-address notices, Lynda V. Mapes and all other subscription-related communica- tions to Circulation Manager, Arnoldia, Arnold 32 Through the Seasons with Sassafras Arboretum, 125 Arborway, Boston, MA 02130- Nancy Rose 3500. Telephone 617.524.1718; fax 617.524.1418; e-mail [email protected] Front cover: A specimen of Yeddo spruce (Picea Arnold Arboretum members receive a subscrip- jezoensis, accession 502-77-A) displayed new seed tion to Arnoldia as a membership benefit. To cones and shoots on May 6, 2016. Photo by William become a member or receive more information, (Ned) Friedman. please call Wendy Krauss at 617.384.5766 or email [email protected] Inside front cover: A showy pink-flowered cultivar Postmaster: Send address changes to of flowering dogwood (Cornus florida‘Royal Red’, accession 13-61-A) was in full bloom on May 9, 2016. -

Special Olympics Bowling Win at State

Thursday, April 4, 2019 $1.00 For more, log on to: www.mycameronnews.com Cameron, Missouri Special Olympics Results of General Basketball Team Brings Municipal Elections By Tara Wallace Editor Home Gold [email protected] There were three questions put before Cameron voters on Tuesday, April 2. The results are as follows: • Julie Ausmas is the newest member on Cameron City Council. She received 606 votes (62 percent) to her opponents 357 votes (38 percent); • Larry Harper is on the Road District; • 911 ACCD Question passed with 3707 votes in favor (66.40 percent) and 1,876 votes opposed (33.60 percent) across the four counties that make up the district. Only 13 percent of registered voters Newest Member of Cameron City participated in Clinton County and 15 Council Julie Ausmus percent in DeKalb County. Special Olympics Photo by Mattea Johnson Dakota Hensley, Kourtney Calloway, Garrett Klawuhn, Johnnie Eggman, John Barber, Billy Beardsley. Not pictured: Jeremy Kingsley, Jacob Grayson, and Head Coach Matthew Johnson Bowling Win at State By Jenni Clemons In order to make it to the State Games Contributed the team had to play and win four games between Districts, Regionals, and then The Special Olympic State Basketball State. The Regional games were not held due Games were held in St. Joseph on Saturday, to bad weather. The Punishers players are May 30, at Benton High School. The State from St Joseph, Union Star, Maysville, and Games were attended by fans from all across Cameron. Head Coach Matthew Johnson is Missouri. The Punishers team played both an employee of Missouri Quality Care in Oak Hill and Kansas City Metro on Saturday. -

The Dutchman Vol. 6, No. 5 Earl F

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College The Dutchman / The eP nnsylvania Dutchman Pennsylvania Folklife Society Collection Magazine Summer 1955 The Dutchman Vol. 6, No. 5 Earl F. Robacker Olive G. Zehner Cornelius Weygandt Henry J. Kauffman Albert I. Drachman See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/dutchmanmag Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, American Material Culture Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Cultural History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Folklore Commons, Genealogy Commons, German Language and Literature Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, History of Religion Commons, Linguistics Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Robacker, Earl F.; Zehner, Olive G.; Weygandt, Cornelius; Kauffman, Henry J.; Drachman, Albert I.; Graeff, Arthur D.; and Heller, Edna Eby, "The Dutchman Vol. 6, No. 5" (1955). The Dutchman / The Pennsylvania Dutchman Magazine. 5. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/dutchmanmag/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Folklife Society Collection at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Dutchman / The eP nnsylvania Dutchman Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Earl F. Robacker, Olive G. Zehner, Cornelius Weygandt, Henry J. Kauffman, Albert I. Drachman, Arthur D. Graeff, and Edna Eby Heller This book is available at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/dutchmanmag/5 75 Cents Summer, 1955 Vol. -

1999 Consolidated HPC Reports, Memos, & Attachments

McHenry County Historic Preservation Commission 1999 ANNUAL REPORTS McHENRY COUNTY HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION FY 1998-1999 ANNUAL REPORT OVERVIEW Development in McHenry County continues. Rural subdivisions and land expansion by municipalities hold the potential for continued loss of historic structures and scenic rural vistas. In light of development trends, the McHenry County Historic Preservation Commission is committed to creating a balanced perspective for the County, to help preserve that which is best and to support a county-wide coordinated effort to identify and protect valuable sites and structures before development encroaches upon them. I. Cases Reviewed In fiscal year 1998-1999 the Commission had no cause to review any Certificates of Appropriateness. No Certificates of Economic Hardship were issued. II. Designations (See Appendix A.) In fiscal year 1997-98 the Commission held two (2) public hearings for local land mark designations: • #HP 99-01: Woodstock Street, Huntley, Illinois, was formally designated 1 McHenry County's fourteenth local landmark on the 16 h of February 1999 by a unanimous vote of the County Board. Located entirely within the corporate limits of the Village of Huntley in Grafton Township, Woodstock Street is one of the last remaining brick streets in McHenry County. The street's 1260 foot surface is lined with brick pavers popularized in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The street is home to many of the village's historic homes. It also served as the major north south transportation link in Huntley until Route 47 was completed in the 1930s. A complete history is included in Appendix A. -

SUMMER 2015 Edited by David Martin

Volume 24 : Issue 2 Edited by David Martin SUMMER 2015 Edited by David Martin Volume 24 Issue 2 Summer 2015 1 Copyright © 2015, Fine Lines, Inc PO Box 241713 Omaha, NE 68124 www.finelines.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Fine Lines, Inc. Cover Photo Credits Front Cover: Tina Fey © Amanda Caillau Back Cover: Kaleidescope 10 © Kristy Stark Knapp Times 10 pt. is used throughout this publication. First Edition 2 David Martin Senior Editors: Managing Editor Stu Burns Omaha, NE Board of Directors Marcia Forecki Council Bluffs, IA Steve Gehring Chairman of the Board Attorney Special Editors: Omaha, NE Lee Bachand Omaha, NE David Martin Kris Bamesberger Omaha, NE President Carolyn Bergeron Omaha, NE English Teacher Janet Bonet Omaha, NE Omaha, NE Kayla Engelhaupt Omaha, NE Marcia Forecki Council Bluffs, IA David Mainelli Musician/Businessman Rose Gleisberg Bellevue, NE Omaha, NE Kathie Haskins Omaha, NE Kaitlyn Hayes Omaha, NE Dorothy Miller Abigail Hills Omaha, NE English Teacher, retired Jim Holthus Omaha, NE Kearney, NE David Hufford Omaha, NE Anne James Bellevue, NE Tom Pappas Harrison Johnson Omaha, NE English Teacher, retired Tim Kaldahl Omaha, NE Lincoln, NE Ashley Kresl Omaha, NE Anne Lloyd Omaha, NE Advisers Margie Lukas Omaha, NE Wendy Lundeen Omaha, NE Dr. Stan Maliszewski Yolie Martin Omaha, NE Educational -

Press Release

Press Release 3BO and Sutton Grange Winery are thrilled to present Rock In the Vines! Featuring a line up of 10 Aussie Rock legends, this is the Australia Day weekend concert not to be missed! Performing your favourite superstar acts from the 70s, 80s, and 90s for one day only at Sutton Grange Winery on Friday 27th January, 2017. Tickets go on sale 27th October 2016 via Ticketmaster.com.au. We can now unveil the following acts…(drum roll please): Ross Wilson Now Listen! Mr Eagle Rock, ROSS WILSON, 2 time ARIA Hall of Fame Inductee, founder of Daddy Cool and Mondo Rock continues to have a Hell Of A Time while Living In The Land Of Oz. Always believing Ego Is Not A Dirty Word, the Skyhooks and Jo Jo Zep producer hasn't stagnated by Living In the 70's, but continued moving like The Fugitive Kind through the Summer of 81 into the 21st Century following his credo All I Wanna Do Is Rock. When the Chemistry is right to Come Back Again, he'll get up off his Bed Of Nails, bring A Touch of Paradise to your Cool World and examine your State of the Heart. With No Time to lose practicing Primitive Love Rites in Primal Park, Things Are Hotting Up with Wilson's song I Come In Peace being covered and becoming Joe Cocker’s last hit single. Come Said The Boy, to a Ross Wilson show in a venue near you, because we all know You've All Got To Go! Richard Clapton When he was 16 he inveigled his way into a Sydney hotel to hang out with the Rolling Stones.