REINVENTING SAVINGS BONDS: Policy Changes to Increase Private Savings 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saving the Information Commons a New Public Intere S T Agenda in Digital Media

Saving the Information Commons A New Public Intere s t Agenda in Digital Media By David Bollier and Tim Watts NEW AMERICA FOUNDA T I O N PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE Saving the Information Commons A Public Intere s t Agenda in Digital Media By David Bollier and Tim Watts Washington, DC Ack n owl e d g m e n t s This report required the support and collaboration of many people. It is our pleasure to acknowledge their generous advice, encouragement, financial support and friendship. Recognizing the value of the “information commons” as a new paradigm in public policy, the Ford Foundation generously supported New America Foundation’s Public Assets Program, which was the incubator for this report. We are grateful to Gigi Sohn for helping us develop this new line of analysis and advocacy. We also wish to thank The Open Society Institute for its important support of this work at the New America Foundation, and the Center for the Public Domain for its valuable role in helping Public Knowledge in this area. Within the New America Foundation, Michael Calabrese was an attentive, helpful colleague, pointing us to useful literature and knowledgeable experts. A special thanks to him for improv- ing the rigor of this report. We are also grateful to Steve Clemons and Ted Halstead of the New America Foundation for their role in launching the Information Commons Project. Our research and writing of this report owes a great deal to a network of friends and allies in diverse realms. For their expert advice, we would like to thank Yochai Benkler, Jeff Chester, Rob Courtney, Henry Geller, Lawrence Grossman, Reed Hundt, Benn Kobb, David Lange, Jessica Litman, Eben Moglen, John Morris, Laurie Racine and Carrie Russell. -

THE FUTURE of IDEAS This Work Is Licensed Under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (US/V3.0)

less_0375505784_4p_fm_r1.qxd 9/21/01 13:49 Page i THE FUTURE OF IDEAS This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (US/v3.0). Noncommercial uses are thus permitted without any further permission from the copyright owner. Permissions beyond the scope of this license are administered by Random House. Information on how to request permission may be found at: http://www.randomhouse.com/about/ permissions.html The book maybe downloaded in electronic form (freely) at: http://the-future-of-ideas.com For more permission about Creative Commons licenses, go to: http://creativecommons.org less_0375505784_4p_fm_r1.qxd 9/21/01 13:49 Page iii the future of ideas THE FATE OF THE COMMONS IN A CONNECTED WORLD /// Lawrence Lessig f RANDOM HOUSE New York less_0375505784_4p_fm_r1.qxd 9/21/01 13:49 Page iv Copyright © 2001 Lawrence Lessig All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Random House and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Lessig, Lawrence. The future of ideas : the fate of the commons in a connected world / Lawrence Lessig. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-375-50578-4 1. Intellectual property. 2. Copyright and electronic data processing. 3. Internet—Law and legislation. 4. Information society. I. Title. K1401 .L47 2001 346.04'8'0285—dc21 2001031968 Random House website address: www.atrandom.com Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 24689753 First Edition Book design by Jo Anne Metsch less_0375505784_4p_fm_r1.qxd 9/21/01 13:49 Page v To Bettina, my teacher of the most important lesson. -

Phonograph and Audio Collection

McLean County Museum of History Phonograph and Audio Collection Processed by Aingeal Stone Winter/Spring 2014 Jim Hall Winter 2018 Collection Information VOLUME OF COLLECTION: 10 Boxes COLLECTION DATES: 1935-2007; mostly 1946-58. RESTRICTIONS: None REPRODUCTION RIGHTS: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from the McLean County Museum of History ALTERNATIVE FORMATS: None OTHER FINDING AIDS: None LOCATION: Archives NOTES: Brief History The history of McLean County has been recorded and captured on vinyl covering a variety of subjects in a variety of ways. From the speeches of native born politicians to the music of area residents, these examples of the past are here collected and preserved for the future. Scope This collection includes audio recordings of speeches, meetings, music on cassette and 78, 45, 33 1/3 rpm discs. Box 1 contains phonographs exclusively pertaining to Adlai E. Stevenson II, a Bloomington-born politician. Box 2 contains phonographs pertaining to local news and music, and world news. Box 3 contains phonographs pertaining to local musical performances, national radio and television programs, presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy, and Christmas music. Box 4 contains phonographs of musical numbers by various performers and barbershop quartets. Box 5 contains small format phonographs and cassettes of local performers’ music. Box 6 contains large format phonographs of Wilding Picture Productions recordings concerning economics and a Stevenson Bandwagon Album. Boxes 7 and 8 contain CD’s of local performers. Box 9 contains phonographs of musical numbers by local performers. Boxes 10 and 11 contain phonographs of performance by local schools and churches. -

The Failure of Bilingual Education. INSTITUTION Center for Equal Opportunity, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 636 FL 023 750 AUTHOR Amselle, Jorge, Ed. TITLE The Failure of Bilingual Education. INSTITUTION Center for Equal Opportunity, Washington, DC. PUB DATE [96] NOTE 126p. AVAILABLE FROMCenter for Equal Opportunity, 815 15th St. N.W., Suite 928, Washington, DC 20005; Tel: 202-639-0803; Fax: 202-639-0827. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS -'"Bilingual Education; Court Litigation; English (Second Language); *English Only Movement; Government Role; *Intercultural Communication; *Language Mainterance; Language Research; Language Skills; Limited English Speaking; Minority Groups; *Multicultural Education; Second Language Learning; *Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS California ABSTRACT This monograph is based an a conference on bilingual education held by the Center for Equal Opportunity (CEO) in September, 1995 in Washington, D.C. CEO made repeated attempts to secure speakers representing the pro-bilingu41 education viewpoint; the paper by Portes and Schauffler represents this view. Papers presented include: "Introduction: One Nation, One Common Language" (Linda Chavez); "Bilingual Education and the Role of Government Li Preserving Our Common Language" (Toby Roth); "Is ;Jilingual Education an Effective Educational Tool? (Christine Rossell); "What Bilingual Education Rcsearr't Tells Us" (Keith Baker) ;"The Pclitics of Bilingual Education Revisited" (Rosalie Pedalino Porter); "Realizing Democratic Ideals with Bilingual Education" (Irma N. Guadarrama); "Language and the Second Generation: Bilingualism Yesterday and Today" (Alejandro Fortes and Richard Schauffler); "Educating California's Immigrant Children" (Wayne A. Cornelius); "Breaking the Bilingual Lobby's Stranglehold" (Sally Peterson); "Parental Choice in Burbank, California" (Lila Ramirez); "Bilingual Education Alternatives" (Patricia Whitelaw-Hill); "Bilingual Education in the Classroom" (Suzanne Guerrero); and "One Parent's Story" (Miguel Alvarado). -

American Folk Music and the Radical Left Sarah C

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2015 If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left Sarah C. Kerley East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kerley, Sarah C., "If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2614. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2614 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left —————————————— A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History —————————————— by Sarah Caitlin Kerley December 2015 —————————————— Dr. Elwood Watson, Chair Dr. Daryl A. Carter Dr. Dinah Mayo-Bobee Keywords: Folk Music, Communism, Radical Left ABSTRACT If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left by Sarah Caitlin Kerley Folk music is one of the most popular forms of music today; artists such as Mumford and Sons and the Carolina Chocolate Drops are giving new life to an age-old music. -

Order Form Full

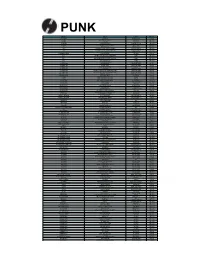

PUNK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 100 DEMONS 100 DEMONS DEATHWISH INC RM90.00 4-SKINS A FISTFUL OF 4-SKINS RADIATION RM125.00 4-SKINS LOW LIFE RADIATION RM114.00 400 BLOWS SICKNESS & HEALTH ORIGINAL RECORD RM117.00 45 GRAVE SLEEP IN SAFETY (GREEN VINYL) REAL GONE RM142.00 999 DEATH IN SOHO PH RECORDS RM125.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (200 GR) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (GREEN) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 YOU US IT! COMBAT ROCK RM120.00 A WILHELM SCREAM PARTYCRASHER NO IDEA RM96.00 A.F.I. ANSWER THAT AND STAY FASHIONABLE NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. BLACK SAILS IN THE SUNSET NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. SHUT YOUR MOUTH AND OPEN YOUR EYES NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. VERY PROUD OF YA NITRO RM119.00 ABEST ASYLUM (WHITE VINYL) THIS CHARMING MAN RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE ARCHIVE TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM108.00 ACCUSED, THE BAKED TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE NASTY CUTS (1991-1993) UNREST RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE OH MARTHA! UNREST RECORDS RM93.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (EARA UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (SUBC UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACHTUNGS, THE WELCOME TO HELL GOING UNDEGROUND RM96.00 ACID BABY JESUS ACID BABY JESUS SLOVENLY RM94.00 ACIDEZ BEER DRINKERS SURVIVORS UNREST RM98.00 ACIDEZ DON'T ASK FOR PERMISSION UNREST RM98.00 ADICTS, THE AND IT WAS SO! (WHITE VINYL) NUCLEAR BLAST RM127.00 ADICTS, THE TWENTY SEVEN DAILY RECORDS RM120.00 ADOLESCENTS ADOLESCENTS FRONTIER RM97.00 ADOLESCENTS BRATS IN BATTALIONS NICKEL & DIME RM96.00 ADOLESCENTS LA VENDETTA FRONTIER RM95.00 ADOLESCENTS -

FOIA Request HH 7.12.18 (00041407).DOCX

New York Office Washington, D.C. Office 40 Rector Street, 5th Fl. 700 14th St., NW, Ste. 600 New York, NY 10006-1738 Washington, D.C. 20005 T 212.965.2200 / F 212.226.7592 T 202.682.1300 / F 202.682.1312 www.naacpldf.org August 7, 2018 VIA FEDERAL E-RULEMAKING PORTAL & EMAIL Ms. Jennifer Jessup Departmental Paperwork Clearance Officer Department of Commerce Room 6616 14th and Constitution Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20230 http://www.regulations.gov (Docket # USBC-2018-0005) [email protected] Re: Comments on 2020 Census, Including Proposed Information Collection The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (“LDF”), our country’s first and foremost civil rights and racial justice organization, appreciates the opportunity to provide comments in response to the Federal Register notice (the “Notice”). Since its founding in 1940, one of LDF’s core missions has been the achievement of the full, equal, and active participation of all Americans, particularly Black Americans, in the political process.1 Consistent with this mission, LDF has engaged in public education campaigns to inform communities, particularly Black communities,2 about prior censuses and the upcoming 2020 Census, explaining the importance of the Census count and advocating for various changes to the Census, including reforming how incarcerated people are counted on Census Day and using a combined race and ethnicity question.3 Most recently, LDF has vigorously opposed and sought public records on the Census Bureau’s decision to add a citizenship status 1 LDF has been a separate entity from the NAACP, and its state branches, since 1957. -

Myriad Approaches to Death in Edgar Allan Poe's Tales of Terror Jenni A

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2011 Living in the Mystery: Myriad Approaches to Death in Edgar Allan Poe's Tales of Terror Jenni A. Shearston Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Shearston, Jenni A., "Living in the Mystery: Myriad Approaches to Death in Edgar Allan Poe's Tales of Terror" (2011). All Regis University Theses. 550. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/550 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University Regis College Honors Theses Disclaimer Use of the materials available in the Regis University Thesis Collection (“Collection”) is limited and restricted to those users who agree to comply with the following terms of use. Regis University reserves the right to deny access to the Collection to any person who violates these terms of use or who seeks to or does alter, avoid or supersede the functional conditions, restrictions and limitations of the Collection. The site may be used only for lawful purposes. The user is solely responsible for knowing and adhering to any and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating or pertaining to use of the Collection. All content in this Collection is owned by and subject to the exclusive control of Regis University and the authors of the materials. -

LESSONS from SEED a National Demonstration of Child Development Accounts Lessons from SEED, a National Demonstration of Child Development Accounts

LESSONS FROM SEED a National Demonstration of Child Development Accounts Lessons from SEED, a National Demonstration of Child Development Accounts Editors: Michael Sherraden & Julia Stevens Authors: Deborah Adams, Ray Boshara, Margaret Clancy, Reid Cramer, Bob Friedman, Rochelle Howard, Karol Krotki, Ellen Marks, Lisa Mensah, Bryan Rhodes, Carl Rist, Edward Scanlon, Leigh Tivol, Trina Williams Shanks, & Robert Zager September 2010 Acknowledgments: The authors gratefully acknowledge the funders who made the SEED initiative possible: Ford Foundation, Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, Lumina Foundation for Education, Charles and Helen Schwab Foundation, Jim Casey Youth Opportunity Initiative, Citi Foundation, Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund, MetLife Foundation, Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund, Edwin Gould Foundation for Children, and W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Our thanks also go to the SEED Partners, who made SEED happen on the ground and facilitated this research: Beyond Housing, Boys & Girls Club of Delaware, Cherokee Nation, Foundation Communities, Fundacion Chana y Samuel Levis, Harlem Children’s Zone, Juma Ventures, Mile High United Way, Oakland Livingston Human Service Agency (OLHSA), People for People, Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, Southern Good Faith Fund, & State of Oklahoma. We are grateful, too, to the members of the SEED Research Advisory Council for their leadership and support throughout the SEED initiative and for their guidance, comments, and suggestions on this report: Benita Melton of the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, Robert Plotnick of the Daniel J. Evans School of Public Affairs, Frank DeGiovanni and Kilolo Kijakazi of the Ford Foundation, Christine Robinson of Stillwater Consulting, William Gale of The Brookings Institution, Lawrence Aber of The Steinhardt School of Education, Duncan Lindsey of the UCLA School of Public Affairs, and Larry Davis of the University of Pittsburgh. -

“The Mission of the Church in the New America” with Guest, Charles J

1 Franciscan University Presents “The Mission of the Church in the New America” With guest, Charles J. Chaput, O.F.M. Cap. The Mission of the Church in the New America: Augustine, Francis and the future By Charles J. Chaput, O.F.M. Cap Much of what I say today is adapted from Strangers in a Strange Land, a book I’ve written that will be published by Henry Holt & Co. in February. The good news is that if you don’t like the talk, I’ve saved you $20. The other good news is that if you do like the talk, there’s a lot more of the same in the book. The not-quite-so good news is that you’ll have to buy it. Please. So let’s begin. Back when dinosaurs walked the earth, and the world and I were young – or at least younger -- the singer Bobby McFerrin had a hit tune called “Don’t Worry, Be Happy.” The lyrics were simple. Basically he just sang the words “don’t worry, be happy” more than 30 times in the space of four minutes. But the song was fun and innocent, and it made people smile. So it was very popular. That was in 1988. Before the First Iraq War. Before 9/11. Before Al Qaeda, Afghanistan, the Second Iraq War, the 2008 economic meltdown, the Benghazi fiasco, the Syria fiasco, the IRS scandal, the HHS mandate, the Obergefell decision, the ghoulish Planned Parenthood videos, the refugee crisis, Boko Haram, ISIS, and the terror attacks in Paris, San Bernardino and Orlando. -

Yes We Can: the Emergence of Millennials As a Political Generation 5 Public Action

february 2009 Yes We Can The Emergence of Millennials As a Political Generation neil howe and reena nadler next social contract initiative New America Foundation © 2009 New America Foundation This report carries a Creative Commons license, which permits non- commercial re-use of New America content when proper attribution is provided. This means you are free to copy, display and distribute New America’s work, or include our content in derivative works, under the following conditions: • Attribution. You must clearly attribute the work to the New America Foundation, and provide a link back to www.Newamerica.net. • Noncommercial. You may not use this work for commercial purposes without explicit prior permission from New America. • Share Alike. If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under a license identical to this one. For the full legal code of this Creative Commons license, please visit www.creativecommons.org. If you have any questions about citing or re- using New America content, please contact us. Executive Summary The 2008 presidential election unleashed a potent new and conventionality, a preference for group consensus, an force in American politics. It is the Millennial Generation: aversion to personal risk, and a self-image as special and Americans born since 1982, now age 26 and under. as worthy of protection. The generation that has already Politicians and pundits alike were surprised by the waves transformed K-12 classrooms, the enlisted ranks, college of young volunteers who manned the campaign front lines, campuses, and the entry-level workforce is now beginning phone banking, blogging, canvassing door-to-door, and to transform politics. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least.