Contribution of C3G and Other Gefs to Liver Cancer Development and Progression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Proximal Signaling Network of the BCR-ABL1 Oncogene Shows a Modular Organization

Oncogene (2010) 29, 5895–5910 & 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9232/10 www.nature.com/onc ORIGINAL ARTICLE The proximal signaling network of the BCR-ABL1 oncogene shows a modular organization B Titz, T Low, E Komisopoulou, SS Chen, L Rubbi and TG Graeber Crump Institute for Molecular Imaging, Institute for Molecular Medicine, Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, California NanoSystems Institute, Department of Molecular and Medical Pharmacology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA BCR-ABL1 is a fusion tyrosine kinase, which causes signaling effects of BCR-ABL1 toward leukemic multiple types of leukemia. We used an integrated transformation. proteomic approach that includes label-free quantitative Oncogene (2010) 29, 5895–5910; doi:10.1038/onc.2010.331; protein complex and phosphorylation profiling by mass published online 9 August 2010 spectrometry to systematically characterize the proximal signaling network of this oncogenic kinase. The proximal Keywords: adaptor protein; BCR-ABL1; phospho- BCR-ABL1 signaling network shows a modular and complex; quantitative mass spectrometry; signaling layered organization with an inner core of three leukemia network; systems biology transformation-relevant adaptor protein complexes (Grb2/Gab2/Shc1 complex, CrkI complex and Dok1/ Dok2 complex). We introduced an ‘interaction direction- ality’ analysis, which annotates static protein networks Introduction with information on the directionality of phosphorylation- dependent interactions. In this analysis, the observed BCR-ABL1 is a constitutively active oncogenic fusion network structure was consistent with a step-wise kinase that arises through a chromosomal translocation phosphorylation-dependent assembly of the Grb2/Gab2/ and causes multiple types of leukemia. It is found in Shc1 and the Dok1/Dok2 complexes on the BCR-ABL1 many cases (B25%) of adult acute lymphoblastic core. -

Protein-Coding Variants Implicate Novel Genes Related to Lipid Homeostasis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/352674; this version posted June 30, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 PROTEIN-CODING VARIANTS IMPLICATE NOVEL GENES RELATED TO LIPID HOMEOSTASIS 2 CONTRIBUTING TO BODY FAT DISTRIBUTION 3 Anne E Justice¥,1,2, Tugce Karaderi¥,3,4, Heather M Highland¥,1,5, Kristin L Young¥,1, Mariaelisa Graff¥,1, 4 Yingchang Lu¥,6,7,8, Valérie Turcot9, Paul L Auer10, Rebecca S Fine11,12,13, Xiuqing Guo14, Claudia 5 Schurmann7,8, Adelheid Lempradl15, Eirini Marouli16, Anubha Mahajan3, Thomas W Winkler17, Adam E 6 Locke18,19, Carolina Medina-Gomez20,21, Tõnu Esko11,13,22, Sailaja Vedantam11,12,13, Ayush Giri23, Ken Sin 7 Lo9, Tamuno Alfred7, Poorva Mudgal24, Maggie CY Ng24,25, Nancy L Heard-Costa26,27, Mary F Feitosa28, 8 Alisa K Manning11,29,30 , Sara M Willems31, Suthesh Sivapalaratnam30,32,33, Goncalo Abecasis18, Dewan S 9 Alam34, Matthew Allison35, Philippe Amouyel36,37,38, Zorayr Arzumanyan14, Beverley Balkau39, Lisa 10 Bastarache40, Sven Bergmann41,42, Lawrence F Bielak43, Matthias Blüher44,45, Michael Boehnke18, Heiner 11 Boeing46, Eric Boerwinkle47,48, Carsten A Böger49, Jette Bork-Jensen50, Erwin P Bottinger7, Donald W 12 Bowden24,25,51, Ivan Brandslund52,53, Linda Broer21, Amber A Burt54, Adam S Butterworth55,56, Mark J 13 Caulfield16,57, Giancarlo Cesana58, John C Chambers59,60,61,62,63, Daniel I Chasman11,64,65,66, Yii-Der Ida 14 Chen14, Rajiv Chowdhury55, Cramer Christensen67, -

Molecular Cytogenetics Biomed Central

Molecular Cytogenetics BioMed Central Research Open Access FISH mapping of Philadelphia negative BCR/ABL1 positive CML Anna Virgili1, Diana Brazma1, Alistair G Reid2, Julie Howard-Reeves1, Mikel Valgañón1, Anastasios Chanalaris1, Valeria AS De Melo2, David Marin2, Jane F Apperley2, Colin Grace1 and Ellie P Nacheva*1 Address: 1Molecular Cytogenetics, Academic Haematology, Royal Free and UCL Medical School, Rowland Hill Street, London, NW3 2PF, UK and 2Imperial College, Faculty Medicine, Hammersmith Hospital, Dept of Haematology, Du Cane Road, London, W12 ONN, UK Email: Anna Virgili - [email protected]; Diana Brazma - [email protected]; Alistair G Reid - [email protected]; Julie Howard-Reeves - [email protected]; Mikel Valgañón - [email protected]; Anastasios Chanalaris - [email protected]; Valeria AS De Melo - [email protected]; David Marin - [email protected]; Jane F Apperley - [email protected]; Colin Grace - [email protected]; Ellie P Nacheva* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 18 July 2008 Received: 21 May 2008 Accepted: 18 July 2008 Molecular Cytogenetics 2008, 1:14 doi:10.1186/1755-8166-1-14 This article is available from: http://www.molecularcytogenetics.org/content/1/1/14 © 2008 Virgili et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) is a haematopoietic stem cell disorder, almost always characterized by the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph), usually due to t(9;22)(q34;q11) or its variants. -

Identification and Characterization of RHOA-Interacting Proteins in Bovine Spermatozoa1

BIOLOGY OF REPRODUCTION 78, 184–192 (2008) Published online before print 10 October 2007. DOI 10.1095/biolreprod.107.062943 Identification and Characterization of RHOA-Interacting Proteins in Bovine Spermatozoa1 Sarah E. Fiedler, Malini Bajpai, and Daniel W. Carr2 Department of Medicine, Oregon Health & Sciences University and Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Portland, Oregon 97239 ABSTRACT Guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) catalyze the GDP for GTP exchange [2]. Activation is negatively regulated by In somatic cells, RHOA mediates actin dynamics through a both guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (RHO GDIs) GNA13-mediated signaling cascade involving RHO kinase and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) [1, 2]. Endogenous (ROCK), LIM kinase (LIMK), and cofilin. RHOA can be RHO can be inactivated via C3 exoenzyme ADP-ribosylation, negatively regulated by protein kinase A (PRKA), and it and studies have demonstrated RHO involvement in actin-based interacts with members of the A-kinase anchoring (AKAP) cytoskeletal response to extracellular signals, including lyso- family via intermediary proteins. In spermatozoa, actin poly- merization precedes the acrosome reaction, which is necessary phosphatidic acid (LPA) [2–4]. LPA is known to signal through for normal fertility. The present study was undertaken to G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [4, 5]; specifically, LPA- determine whether the GNA13-mediated RHOA signaling activated GNA13 (formerly Ga13) promotes RHO activation pathway may be involved in acrosome reaction in bovine through GEFs [4, 6]. Activated RHO-GTP then signals RHO caudal sperm, and whether AKAPs may be involved in its kinase (ROCK), resulting in the phosphorylation and activation targeting and regulation. GNA13, RHOA, ROCK2, LIMK2, and of LIM-kinase (LIMK), which in turn phosphorylates and cofilin were all detected by Western blot in bovine caudal inactivates cofilin, an actin depolymerizer, the end result being sperm. -

G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Signaling and Polarized Actin Dynamics Drive

RESEARCH ARTICLE elifesciences.org G-protein-coupled receptor signaling and polarized actin dynamics drive cell-in-cell invasion Vladimir Purvanov, Manuel Holst, Jameel Khan, Christian Baarlink, Robert Grosse* Institute of Pharmacology, University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany Abstract Homotypic or entotic cell-in-cell invasion is an integrin-independent process observed in carcinoma cells exposed during conditions of low adhesion such as in exudates of malignant disease. Although active cell-in-cell invasion depends on RhoA and actin, the precise mechanism as well as the underlying actin structures and assembly factors driving the process are unknown. Furthermore, whether specific cell surface receptors trigger entotic invasion in a signal-dependent fashion has not been investigated. In this study, we identify the G-protein-coupled LPA receptor 2 (LPAR2) as a signal transducer specifically required for the actively invading cell during entosis. We find that 12/13G and PDZ-RhoGEF are required for entotic invasion, which is driven by blebbing and a uropod-like actin structure at the rear of the invading cell. Finally, we provide evidence for an involvement of the RhoA-regulated formin Dia1 for entosis downstream of LPAR2. Thus, we delineate a signaling process that regulates actin dynamics during cell-in-cell invasion. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.02786.001 Introduction Entosis has been described as a specialized form of homotypic cell-in-cell invasion in which one cell actively crawls into another (Overholtzer et al., 2007). Frequently, this occurs between tumor cells such as breast, cervical, or colon carcinoma cells and can be triggered by matrix detachment (Overholtzer et al., 2007), suggesting that loss of integrin-mediated adhesion may promote cell-in-cell invasion. -

S41467-020-18249-3.Pdf

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18249-3 OPEN Pharmacologically reversible zonation-dependent endothelial cell transcriptomic changes with neurodegenerative disease associations in the aged brain Lei Zhao1,2,17, Zhongqi Li 1,2,17, Joaquim S. L. Vong2,3,17, Xinyi Chen1,2, Hei-Ming Lai1,2,4,5,6, Leo Y. C. Yan1,2, Junzhe Huang1,2, Samuel K. H. Sy1,2,7, Xiaoyu Tian 8, Yu Huang 8, Ho Yin Edwin Chan5,9, Hon-Cheong So6,8, ✉ ✉ Wai-Lung Ng 10, Yamei Tang11, Wei-Jye Lin12,13, Vincent C. T. Mok1,5,6,14,15 &HoKo 1,2,4,5,6,8,14,16 1234567890():,; The molecular signatures of cells in the brain have been revealed in unprecedented detail, yet the ageing-associated genome-wide expression changes that may contribute to neurovas- cular dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases remain elusive. Here, we report zonation- dependent transcriptomic changes in aged mouse brain endothelial cells (ECs), which pro- minently implicate altered immune/cytokine signaling in ECs of all vascular segments, and functional changes impacting the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and glucose/energy metabolism especially in capillary ECs (capECs). An overrepresentation of Alzheimer disease (AD) GWAS genes is evident among the human orthologs of the differentially expressed genes of aged capECs, while comparative analysis revealed a subset of concordantly downregulated, functionally important genes in human AD brains. Treatment with exenatide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, strongly reverses aged mouse brain EC transcriptomic changes and BBB leakage, with associated attenuation of microglial priming. We thus revealed tran- scriptomic alterations underlying brain EC ageing that are complex yet pharmacologically reversible. -

Aneuploidy: Using Genetic Instability to Preserve a Haploid Genome?

Health Science Campus FINAL APPROVAL OF DISSERTATION Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science (Cancer Biology) Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Submitted by: Ramona Ramdath In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science Examination Committee Signature/Date Major Advisor: David Allison, M.D., Ph.D. Academic James Trempe, Ph.D. Advisory Committee: David Giovanucci, Ph.D. Randall Ruch, Ph.D. Ronald Mellgren, Ph.D. Senior Associate Dean College of Graduate Studies Michael S. Bisesi, Ph.D. Date of Defense: April 10, 2009 Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Ramona Ramdath University of Toledo, Health Science Campus 2009 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandfather who died of lung cancer two years ago, but who always instilled in us the value and importance of education. And to my mom and sister, both of whom have been pillars of support and stimulating conversations. To my sister, Rehanna, especially- I hope this inspires you to achieve all that you want to in life, academically and otherwise. ii Acknowledgements As we go through these academic journeys, there are so many along the way that make an impact not only on our work, but on our lives as well, and I would like to say a heartfelt thank you to all of those people: My Committee members- Dr. James Trempe, Dr. David Giovanucchi, Dr. Ronald Mellgren and Dr. Randall Ruch for their guidance, suggestions, support and confidence in me. My major advisor- Dr. David Allison, for his constructive criticism and positive reinforcement. -

High Throughput Strategies Aimed at Closing the GAP in Our Knowledge of Rho Gtpase Signaling

cells Review High Throughput strategies Aimed at Closing the GAP in Our Knowledge of Rho GTPase Signaling Manel Dahmene 1, Laura Quirion 2 and Mélanie Laurin 1,3,* 1 Oncology Division, CHU de Québec–Université Laval Research Center, Québec, QC G1V 4G2, Canada; [email protected] 2 Montréal Clinical Research Institute (IRCM), Montréal, QC H2W 1R7, Canada; [email protected] 3 Université Laval Cancer Research Center, Québec, QC G1R 3S3, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 21 May 2020; Accepted: 7 June 2020; Published: 9 June 2020 Abstract: Since their discovery, Rho GTPases have emerged as key regulators of cytoskeletal dynamics. In humans, there are 20 Rho GTPases and more than 150 regulators that belong to the RhoGEF, RhoGAP, and RhoGDI families. Throughout development, Rho GTPases choregraph a plethora of cellular processes essential for cellular migration, cell–cell junctions, and cell polarity assembly. Rho GTPases are also significant mediators of cancer cell invasion. Nevertheless, to date only a few molecules from these intricate signaling networks have been studied in depth, which has prevented appreciation for the full scope of Rho GTPases’ biological functions. Given the large complexity involved, system level studies are required to fully grasp the extent of their biological roles and regulation. Recently, several groups have tackled this challenge by using proteomic approaches to map the full repertoire of Rho GTPases and Rho regulators protein interactions. These studies have provided in-depth understanding of Rho regulators specificity and have contributed to expand Rho GTPases’ effector portfolio. Additionally, new roles for understudied family members were unraveled using high throughput screening strategies using cell culture models and mouse embryos. -

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

Increased Microvascular Permeability in Mice Lacking Epac1 (Rapgef3)

Increased microvascular permeability in mice lacking Epac1 (Rapgef3) Kopperud, R. K.; Rygh, C. Brekke; Karlsen, T. V.; Krakstad, C.; Kleppe, R.; Hoivik, E. A.; Bakke, M.; Tenstad, O.; Selheim, F.; Lidén, Å.; Madsen, Lise; Pavlin, T.; Taxt, T.; Kristiansen, Karsten; Curry, F. -R. E.; Reed, R. K.; Døskeland, S. O. Published in: Acta Physiologica DOI: 10.1111/apha.12697 Publication date: 2017 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY-NC-ND Citation for published version (APA): Kopperud, R. K., Rygh, C. B., Karlsen, T. V., Krakstad, C., Kleppe, R., Hoivik, E. A., Bakke, M., Tenstad, O., Selheim, F., Lidén, Å., Madsen, L., Pavlin, T., Taxt, T., Kristiansen, K., Curry, F. -R. E., Reed, R. K., & Døskeland, S. O. (2017). Increased microvascular permeability in mice lacking Epac1 (Rapgef3). Acta Physiologica, 219(2), 441-452. https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.12697 Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Acta Physiol 2017, 219, 441–452 Increased microvascular permeability in mice lacking Epac1 (Rapgef3) † § R. K. Kopperud,1,2,*, C. Brekke Rygh,1,*, T. V. Karlsen,1 C. Krakstad,1 R. Kleppe,1 † ¶ ‡ E. A. Hoivik,1, M. Bakke,1 O. Tenstad,1 F. Selheim,1 A. Liden, 1, L. Madsen,1,3, T. Pavlin,1 T. Taxt,1 K. Kristiansen,3 F.-R. E. Curry,4 R. K. Reed1,2 and S. O. Døskeland1 1 Department of Biomedicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway 2 Centre for Cancer Biomarkers (CCBIO), University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway 3 Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark 4 Department of Physiology and Membrane Biology, School of Medicine, University of California, Davis, CA, USA Received 18 February 2016, Abstract revision requested 15 March Aim: Maintenance of the blood and extracellular volume requires tight con- 2016, trol of endothelial macromolecule permeability, which is regulated by cAMP revision received 12 April 2016, signalling. -

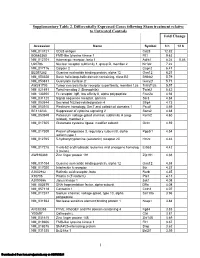

Supplementary Table 2

Supplementary Table 2. Differentially Expressed Genes following Sham treatment relative to Untreated Controls Fold Change Accession Name Symbol 3 h 12 h NM_013121 CD28 antigen Cd28 12.82 BG665360 FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 Flt1 9.63 NM_012701 Adrenergic receptor, beta 1 Adrb1 8.24 0.46 U20796 Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 2 Nr1d2 7.22 NM_017116 Calpain 2 Capn2 6.41 BE097282 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 12 Gna12 6.21 NM_053328 Basic helix-loop-helix domain containing, class B2 Bhlhb2 5.79 NM_053831 Guanylate cyclase 2f Gucy2f 5.71 AW251703 Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12a Tnfrsf12a 5.57 NM_021691 Twist homolog 2 (Drosophila) Twist2 5.42 NM_133550 Fc receptor, IgE, low affinity II, alpha polypeptide Fcer2a 4.93 NM_031120 Signal sequence receptor, gamma Ssr3 4.84 NM_053544 Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 Sfrp4 4.73 NM_053910 Pleckstrin homology, Sec7 and coiled/coil domains 1 Pscd1 4.69 BE113233 Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 Socs2 4.68 NM_053949 Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily H (eag- Kcnh2 4.60 related), member 2 NM_017305 Glutamate cysteine ligase, modifier subunit Gclm 4.59 NM_017309 Protein phospatase 3, regulatory subunit B, alpha Ppp3r1 4.54 isoform,type 1 NM_012765 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2C Htr2c 4.46 NM_017218 V-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog Erbb3 4.42 3 (avian) AW918369 Zinc finger protein 191 Zfp191 4.38 NM_031034 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 12 Gna12 4.38 NM_017020 Interleukin 6 receptor Il6r 4.37 AJ002942 -

Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature Into Vascularized Glomeruli Upon Experimental Transplantation

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature into Vascularized Glomeruli upon Experimental Transplantation † Sazia Sharmin,* Atsuhiro Taguchi,* Yusuke Kaku,* Yasuhiro Yoshimura,* Tomoko Ohmori,* ‡ † ‡ Tetsushi Sakuma, Masashi Mukoyama, Takashi Yamamoto, Hidetake Kurihara,§ and | Ryuichi Nishinakamura* *Department of Kidney Development, Institute of Molecular Embryology and Genetics, and †Department of Nephrology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan; ‡Department of Mathematical and Life Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan; §Division of Anatomy, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; and |Japan Science and Technology Agency, CREST, Kumamoto, Japan ABSTRACT Glomerular podocytes express proteins, such as nephrin, that constitute the slit diaphragm, thereby contributing to the filtration process in the kidney. Glomerular development has been analyzed mainly in mice, whereas analysis of human kidney development has been minimal because of limited access to embryonic kidneys. We previously reported the induction of three-dimensional primordial glomeruli from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Here, using transcription activator–like effector nuclease-mediated homologous recombination, we generated human iPS cell lines that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the NPHS1 locus, which encodes nephrin, and we show that GFP expression facilitated accurate visualization of nephrin-positive podocyte formation in