The Radical Milieu: a Socio-Ecological Analysis of Salafist Radicalization in Aarhus, 2007-17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Conversation with Brandi Carlile by Frank Goodman (7/2007

A Conversation with Brandi Carlile by Frank Goodman (7/2007. Puremusic.com) Raw talent vs. expensive packaging is always a pleasant surprise in the entertainment business. Brandi Carlile is the very rare exception to the rule; she and her band made their own EP, piece by piece with their own money, and Columbia ended up buying it and putting it out. Rolling Stone chose her as one of the 10 Artists to Watch in 2005. The subsequent Columbia full length debut CD contained new versions of a number of the songs from the EP. Relentless gigging leading up to the EP and through the debut had already moved her through various styles with her running twin partners, the Hanseroth Brothers. Tim and Phil had had a hard rock band called The Fighting Machinists, and they bring that honed edge to the BC sound. She is not only a vocalist that can literally do it all, the band itself moves fluidly and convincingly from flat out country right through edgy pop radio rock. She's the only artist you can see on CMT whose main cited influences are Elton John, k.d. lang, Jeff Buckley, and Radiohead. One hears all the time now about how acts getting tunes on Grey's Anatomy can practically launch their career, but in BC's case, there was a Grey's episode that actually debuted a version of the video for Brandi's big song "The Story." Overall, no less than four of her songs have been used in the show. She's hot, super talented, and a driven workaholic. -

Fællesrådenes Adresser

Fællesrådenes adresser Navn Modtager af post Adresse E-mail Kirkebakken 23 Beder-Malling-Ajstrup Fællesråd Jørgen Friis Bak [email protected] 8330 Beder Langelinie 69 Borum-Lyngby Fællesråd Peter Poulsen Borum 8471 Sabro [email protected] Holger Lyngklip Hoffmannsvej 1 Brabrand-Årslev Fællesråd [email protected] Strøm 8220 Brabrand Møllevangs Allé 167A Christiansbjerg Fællesråd Mette K. Hagensen [email protected] 8200 Aarhus N Jeppe Spure Hans Broges Gade 5, 2. Frederiksbjerg og Langenæs Fællesråd [email protected] Nielsen 8000 Aarhus C Hastruptoften 17 Fællesrådet Hjortshøj Landsbyforum Bjarne S. Bendtsen [email protected] 8530 Hjortshøj Poul Møller Blegdammen 7, st. Fællesrådet for Mølleparken-Vesterbro [email protected] Andersen 8000 Aarhus C [email protected] Fællesrådet for Møllevangen-Fuglebakken- Svenning B. Stendalsvej 13, 1.th. Frydenlund-Charlottenhøj Madsen 8210 Aarhus V Fællesrådet for Aarhus Ø og de bynære Jan Schrøder Helga Pedersens Gade 17, [email protected] havnearealer Christiansen 7. 2, 8000 Aarhus C Gudrunsvej 76, 7. th. Gellerup Fællesråd Helle Hansen [email protected] 8220 Brabrand Jakob Gade Øster Kringelvej 30 B Gl. Egå Fællesråd [email protected] Thomadsen 8250 Egå Navn Modtager af post Adresse E-mail [email protected] Nyvangsvej 9 Harlev Fællesråd Arne Nielsen 8462 Harlev Herredsvej 10 Hasle Fællesråd Klaus Bendixen [email protected] 8210 Aarhus Jens Maibom Lyseng Allé 17 Holme-Højbjerg-Skåde Fællesråd [email protected] -

Aarhus Kommune Forudsætninger for Forventet Regnskab Efter

Aarhus Kommune Forventet regnskab 1. kvartal 2018 Forventet Forventet forbrug i % af regnskab, regnskab, Aarhus Kommune Budget 2018 Forbrug Difference budget 0. kvartal 1. kvartal 2018 2018 Busdrift 219101 Kørselsudgifter 423.334.000 118.069.734 28% 431.469.512 438.908.000 15.574.000 219105 Bus IT og øvrige udgifter 8.949.000 1.823.492 20% 8.525.000 15.428.000 6.479.000 219501 Rejsekort - busser 17.415.000 3.671.072 21% 17.464.000 16.894.000 -521.000 219120 Indtægter -256.931.000 -67.712.827 26% -256.931.000 -257.890.000 -959.000 219125 Regionalt tilskud 0 0 0 0 0 I alt 192.767.000 55.851.471 29% 200.527.512 213.340.000 20.573.000 Flextrafik 219920 Handicapkørsel 13.474.000 2.478.091 18% 13.474.000 13.278.000 -196.000 219922 Flexture 983.000 236.655 24% 983.000 983.000 0 219924 Flexbus 0 0 0 0 0 219926 Kommunal kørsel 5.013.200 1.052.788 21% 4.499.600 4.232.000 -781.200 I alt 19.470.200 3.767.534 19% 18.956.600 18.493.000 -977.200 Tog og Letbane 219405 Letbanedrift 57.900.000 -936.691 -2% 41.011.000 40.053.500 -17.846.500 219820 Letbanesekretariatet 223.000 55.750 25% 223.000 223.000 0 Rejsekort - Letbanen 3.002.000 519.005 17% 2.996.000 2.941.000 -61.000 Administration og Øvrige 219801 Trafikselskabet 36.599.000 9.149.750 25% 36.599.000 36.599.000 0 219930 Billetkontrol 8.189.000 3.092.805 38% 8.189.000 9.264.000 1.075.000 219890 Tjenestemandspensioner 508.000 99.111 20% 501.510 502.000 -6.000 Total - netto 318.658.200 71.598.736 22% 309.003.622 321.415.500 2.757.300 Regnskab 2017 til afregning i 2019 ** 225.784 ** Positiv = skyldigt beløb - negativ = tilgodehavende Forudsætninger for forventet regnskab efter 1. -

Social Capital in Gellerup

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Journal of social inclusion. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Espvall, M., Laursen, L. (2014) Social capital in Gellerup. Journal of social inclusion, 5(1): 19-42 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:miun:diva-23812 Social capital in Gellerup ___________________________________________ Line Hille Laursen Psychiatric Research Unit West Denmark Majen Espvall Mid-Sweden University Abstract This paper examines the characteristics of two types of social capital; bridging and bonding social capital among the residents inside and outside a marginalized local community in relation to five demographic features of age, gender, geographical origin and years of residence in the community and in Denmark. The data were collected through a questionnaire, conducted in the largest marginalized high-rise community in Denmark, Gellerup, which is about to undergo an extensive community renewal plan. The study showed that residents in Gellerup had access to bonding and bridging social capital inside and outside Gellerup. Nevertheless, the character of the social capital varied considerably depending on age, geographical origin and years lived in Gellerup. Young residents and people who had lived for many years in Gellerup had more social capital than their counterparts. Furthermore, residents from Arab countries had more bonding relations inside Gellerup, while residents from Northern Europe had more bonding relations outside Gellerup. Keywords: Social capital, marginalized communities, Denmark, bonding social capital, bridging social capital Journal of Social Inclusion, 5(1), 2014 Journal of Social Inclusion, 5(1), 2014 Introduction During the 1960s and 1970s, communities of large-scale high-rise housing estates were built in many countries to meet the after-war housing shortage. -

Aarhus Convention 122 Absurdocene 146 Accountability 7, 12, 16

Index Aarhus Convention 122 Annan, Kofi 85 Absurdocene 146 Antarctica 38–9, 250–251 accountability 7, 12, 16–17, 23, 30, 44, Anthropocene 93–5, 145–8, 185, 186, 245 201 prosecutorial 42 avoiding Faustian 150–151 speciesism 235 humanity and technology in 148–50 activism, shallow 101 anthropocentrism 92, 96–7, 98, 136, 158, Acton, Lord 88 164, 165, 186–7, 235–6, 238, 242, Adams, J.L. 203, 259 245 Addams, Jane 258 Appiah, K.A. 61, 62 advertising 185, 269 Aquinas, Thomas 193, 195 Africa 87, 88, 220 Arab Charter on Humans Rights 122 African Charter on Human and Arab Spring 119 People’s Rights 122 Arctic Council 112 see also individual countries Arendt, H. 6, 26, 95, 96, 203, 205, 206, Agenda 21 39, 110, 111 212, 259 Agenda 2030 281 Argow, W. 255 Alley, R. 74 Aristotelianism 165, 191–2 Amnesty International 101 Aristotle 193, 247 Angus, I. 93–4 artificial intelligence (AI) 145, 148, 251 animals 82–3, 85, 87, 88, 91, 231–4, Asia 88 250–251 see also individual countries commodity value 170 assembly, freedom of 68 Earth systems science 94 assent/consent combination 162, 165, ecocentrism 97, 234–6 166 alternatives to axiological Aung Sang Suu Kyi 6 236–8 austerity 133, 218 human diet 188 Australia 150, 239 intrinsic value of 225, 236, 237, 240, authoritarianism 12, 209 241, 243, 244, 245 authority, exchange and persuasion remaking our covenant with 242–5 systems 130–132, 135, 139 rewilding with compassion 238–41 autocratic governments 118, 247, 248 rights of 15, 25, 230, 238, 243–4 Avatar 223 welfare 243–4 293 Peter Burdon, Klaus Bosselmann and Kirsten Engel - 9781786430878 Downloaded from Elgar Online at 09/26/2021 12:17:04PM via free access 294 The crisis in global ethics and the future of global governance Bacon, Francis 183, 188 Cambodia 192 Bakken, P. -

Christmas Timeline Challenge ___ 1

Christmas Timeline Challenge ___ 1. God first promised to send a Savior a. 1954 AD ___ 2. Irving Berlin’s White Christmas premiered b. 1946 AD ___ 3. The first Christmas card was sold c. 1892 AD ___ 4. Charles Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol d. 1843 AD ___ 5. It’s a Wonderful Life was released e. 1843 AD ___ 6. Handel’s Messiah was first presented f. 1823 AD ___ 7. First Hanukkah festival was observed g. 1776 AD ___ 8. Wise men visited the Christ child h. 1742 AD ___ 9. Michelangelo completed The Holy Family i. 1518 AD ___ 10. Isaiah foretold the virgin birth j. 1504 AD ___ 11. Angels announced Christ’s birth to the shepherds k. 1495 AD ___ 12. The Nutcracker premiered l. circa 300 AD ___ 13. Washington crossed the Delaware on Christmas Eve m.circa 4 BC ___ 14. Leonardo da Vinci painted The Madonna in the Grotto n. circa 4 BC ___ 15. Micah prophesied that Christ would be born in Bethlehem o. circa 4 BC ___ 16. Caesar Augustus called for a census to be taken p. circa 6 BC ___ 17. “A Visit from St. Nicholas” was published anonymously q. 165 BC ___ 18. Raphael painted The Sistine Madonna r. circa 700 BC ___ 19. David’s Psalms referred to the coming Messiah s. circa 700 BC ___ 20. St. Nicholas served as a bishop in Asia Minor t. circa 1000 BC ___ 21. Jesus was born in a stable in Bethlehem u. 4000 BC or earlier C 2012 www.flandersfamily.info Christmas Timeline Challenge ___ 1. -

I Want My MTV”: Music Video and the Transformation of the Sights, Sounds and Business of Popular Music

General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Music History 98T Course Title “I Want My MTV”: Music Video and the Transformation of The Sights, Sounds and Business of Popular Music 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice X Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis X • Social Analysis X Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. This seminar will trace the historical ‘phenomenon” known as MTV (Music Television) from its premiere in 1981 to its move away from the music video in the late 1990s. The goal of this course is to analyze the critical relationships between music and image in representative videos that premiered on MTV, and to interpret them within a ‘postmodern’ historical and cultural context. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Joanna Love-Tulloch, teaching fellow; Dr. Robert Fink, faculty mentor 4. Indicate when do you anticipate teaching this course over the next three years: 2010-2011 Winter Spring X Enrollment Enrollment 5. GE Course Units 5 Proposed Number of Units: Page 1 of 3 6. Please present concise arguments for the GE principles applicable to this course. -

Testmuligheder I Aarhus Kommune

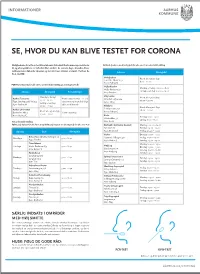

INFORMATIONER SE, HVOR DU KAN BLIVE TESTET FOR CORONA Mulighederne for at få en test bliver løbende forbedret. Der kommer nye teststeder Kviktest (i næsen med kort pind) for alle over 6 år uden tidsbestilling til, og åbningstiderne er forbedret flere steder i de seneste dage. Desuden bliver testkapaciteten løbende tilpasset og sat ind, hvor smitten er størst. Her kan du Adresse Åbningstid få et overblik: Nobelparken Åbent alle ugens dage Jens Chr. Skous Vej 2 8.00 – 20.00 8000 Aarhus C PCR-Test (I halsen) for alle over 2 år med tidsbestilling på coronaprover.dk Vejlby-Risskov Mandag – fredag: 06.00 – 18.00 Vejlby Centervej 51 Lørdag – søndag: 09.00 – 19.00 Adresse Åbningstid Bemærkninger 8240 Risskov Mandag – fredag: Viby Hallen Aarhus Testcenter Handicapparkering er på Åbent alle ugens dage 07.00 – 21.00 Skanderborgvej 224 Tyge Søndergaards Vej 953 testcentret og man skal følge 08.00 – 20.00 Lørdag – søndag: 8260 Viby J 8200 Aarhus N skiltene til kørende 08.00 – 21.00 Filmbyen Åbent alle ugens dage Aarhus Universitet Filmbyen Studie 1 Åbent alle ugens dage 08.00 – 20.00 Bartholins Allé 3 Handicapvenlig 8000 Aarhus C 09.00 – 16.00 8000 Aarhus C Beder Torsdag: 11:00 - 19:00 Kirkebakken 58 Lørdag: 11:00 - 17:00 Test uden tidsbestilling. 8330 Beder PCR test (i halsen for alle fra 2 år og kviktest (i næsen med kort pind) for alle over 6 år. Brabrand - Det Gamle Gasværk Mandag: 09.00 – 19.00 Byleddet 2C Tirsdag: 09.00 – 19.00 Ugedag Sted Åbningstid 8220 Brabrand Fredag: 09.00 – 19.00 Harlev Onsdag: 09:00 - 19:00 Beboerhuset Vest’n, Nyringen 1A Mandage 9.00 - 16.30. -

Read an Excerpt

The Artist Alive: Explorations in Music, Art & Theology, by Christopher Pramuk (Winona, MN: Anselm Academic, 2019). Copyright © 2019 by Christopher Pramuk. All rights reserved. www.anselmacademic.org. Introduction Seeds of Awareness This book is inspired by an undergraduate course called “Music, Art, and Theology,” one of the most popular classes I teach and probably the course I’ve most enjoyed teaching. The reasons for this may be as straightforward as they are worthy of lament. In an era when study of the arts has become a practical afterthought, a “luxury” squeezed out of tight education budgets and shrinking liberal arts curricula, people intuitively yearn for spaces where they can explore together the landscape of the human heart opened up by music and, more generally, the arts. All kinds of people are attracted to the arts, but I have found that young adults especially, seeking something deeper and more worthy of their questions than what they find in highly quantitative and STEM-oriented curricula, are drawn into the horizon of the ineffable where the arts take us. Across some twenty-five years in the classroom, over and over again it has been my experience that young people of diverse religious, racial, and economic backgrounds, when given the opportunity, are eager to plumb the wellsprings of spirit where art commingles with the divine-human drama of faith. From my childhood to the present day, my own spirituality1 or way of being in the world has been profoundly shaped by music, not least its capacity to carry me beyond myself and into communion with the mysterious, transcendent dimension of reality. -

Historical GIS and Folklore Collection in 19Th Century Denmark

Folklore Tracks: Historical GIS and Folklore Collection in 19th Century Denmark Ida Storm a,b,c,d UCLA [email protected] Holly Nicol c UCLA [email protected] Georgia Broughton c UCLA [email protected] Timothy R. Tangherlini a,b,c,e UCLA [email protected] a Conceived of the project b Developed methods and workflow c Extracted and cleaned data d Developed visualizations: maps, charts, graphs e Wrote text Keywords: historical GIS, folklore, history of folklore, ethnography, fieldwork Abstract The “golden age” of folklore collection in 19th century Scandinavia coincided with rapid changes in political, economic, and social organization as well as the rise of the Scandinavian countries broadly conceived of as “nations”. The large folklore collections created during this period were a result of broad field collecting efforts across the region. Tracing the routes of folklorists as they conducted fieldwork helps us discern the developing conceptions of the nation and its cultural boundaries, as well as identify the areas that were most associated, in the minds of collectors, publishers, and scholars, with the cultural locus of the nation. Unraveling the fieldwork methods of early folklore collectors is not a trivial undertaking, and requires a combination of archival research and modern computational methods to reverse engineer the processes by which their collections were created. In this paper, we show how techniques from GIS used in conjunction with time-tested archival research methods can reveal how a folklore collection came into being. Our target corpus is the folklore collections of the Danish school teacher, Evald Tang Kristensen (1843-1929) who, over the course of his fifty-year career, traveled nearly 70,000 kilometers, much of it on foot. -

Smagen Af Æbler I Aarhus Som PDF-Fil

SMAGEN AF ÆBLER I AARHUS Smag på Aarhus, Aarhus Kommune, september 2017, revideret 2020 Foto: Anne Louise Madsen (s. 17), Cecilie Lambertsen & Stine Stampe Johansen (s. 18-27) og Aarhus Kommune www.smagpaaaarhus.dk Indhold 5 Æbler i det offentlige rum 6 Find de gode æblesteder i Aarhus 8 Spiseæbler på store gamle træer Æblehaven i Lystrup, Tilst Bypark, Marienlystparken, Frederiksbjerg Bypark, Engdalgårdsparken, Holme Bypark, Sletvej Æbleskov, Ryparken, parken ved Vil- helmsborg, Lerbjergparken, Langenæsparken, Vejlby Torv, Bomgårdshaven i Mårslet og Donbækhuse i Mindeparken 10 Spiseæbler - nye æblesteder Egå Marina, Harlev Æblelund, Vorrevangsparken, Vår- kærparken, Østerby Mose, Æblelunden Skejby, Veste- reng Æblelund, Skovvejens Æblelund, Viby Torv, Chr. Kiers Plads, Lisbjerg Skov, True Skov, Solbjerg Skov, Åbo Skov, Lillehammervej Legeplads 13 Skovæbler og vilde æbler Brabrandstien, Moesgård Strand, Gellerup skov 14 Viden om æbler 16 Modningsskema 17 Opskrifter 3 Skovvejens Æblelund Vil du også plante og passe frugttræer i dit lokalområde, så find inspiration på www.smagpaaaarhus.dk og skriv til [email protected] 4 Æbletræer i det offentlige rum Du må gerne spise æbler af træer, der står på de offentlige arealer, det vil sige langs stier, i parker og i skovene. Flere steder i Aarhus er der rigtig Aarhusianerne har også taget gode spiseæbler i parker og grønne skovlen i egen hånd – og med områder. Det er blandt andet tid- støtte fra Smag på Aarhus – plan- ligere æbleplantager eller æble- tet frugttræer i deres lokalområder haver fra gamle gårde, der på til glæde for fællesskabet. Ved grund af byudviklingen er blevet at påvirke de nære omgivelser er købt af kommunen. -

8 PAPER 1 'Mass Housing and the Emergence of the 'Concrete Slum

PAPER 1 ‘Mass Housing and the Emergence of the ‘Concrete Slum’ in Denmark in the 1970s & 1980s’ by Mikkel Høghøj (School of Culture and Society, Aarhus University, Denmark) Abstract However, in a Danish context studies of how and why modernist mass housing developed from By investigating how modernist mass housing being emblematic of urban modernity in the 1950s was turned into both an ‘object of criticism’ and and 1960s to serving as a prime marker of societal an ‘object of study’ in the 1970s and early 1980s crisis in the 1970s and 1980s are surprisingly few – Denmark, this articles seeks to bring new perspec- especially when considering how contested these tives to the early history of Danish mass housing. places are today. The present article addresses Even though the rejection of urban modernism this research gap by examining two ways in which constitutes a well-established feld of research Danish mass housing was reappraised during internationally, surprisingly few scholars have so the 190s and 0s ore specifcall, analse far investigated how this played out in a Danish how modernist mass housing transformed as a context. This article addresses this research gap particular type of ‘place’ in Danish society by being by analysing how mass housing was portrayed turned into both an ‘object of criticism’ and an and re-evaluated as a ‘place’ in Danish mass ‘object of study’. Yet, in order to explain this trans- media and popular culture as well as within social formation, certain characteristics of the planning scientifc research from the 190s to the mid- and construction of Danish mass housing in the 1980s.