Lecture 10 Phases, Evaporation & Latent Heat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VISCOSITY of a GAS -Dr S P Singh Department of Chemistry, a N College, Patna

Lecture Note on VISCOSITY OF A GAS -Dr S P Singh Department of Chemistry, A N College, Patna A sketchy summary of the main points Viscosity of gases, relation between mean free path and coefficient of viscosity, temperature and pressure dependence of viscosity, calculation of collision diameter from the coefficient of viscosity Viscosity is the property of a fluid which implies resistance to flow. Viscosity arises from jump of molecules from one layer to another in case of a gas. There is a transfer of momentum of molecules from faster layer to slower layer or vice-versa. Let us consider a gas having laminar flow over a horizontal surface OX with a velocity smaller than the thermal velocity of the molecule. The velocity of the gaseous layer in contact with the surface is zero which goes on increasing upon increasing the distance from OX towards OY (the direction perpendicular to OX) at a uniform rate . Suppose a layer ‘B’ of the gas is at a certain distance from the fixed surface OX having velocity ‘v’. Two layers ‘A’ and ‘C’ above and below are taken into consideration at a distance ‘l’ (mean free path of the gaseous molecules) so that the molecules moving vertically up and down can’t collide while moving between the two layers. Thus, the velocity of a gas in the layer ‘A’ ---------- (i) = + Likely, the velocity of the gas in the layer ‘C’ ---------- (ii) The gaseous molecules are moving in all directions due= to −thermal velocity; therefore, it may be supposed that of the gaseous molecules are moving along the three Cartesian coordinates each. -

Viscosity of Gases References

VISCOSITY OF GASES Marcia L. Huber and Allan H. Harvey The following table gives the viscosity of some common gases generally less than 2% . Uncertainties for the viscosities of gases in as a function of temperature . Unless otherwise noted, the viscosity this table are generally less than 3%; uncertainty information on values refer to a pressure of 100 kPa (1 bar) . The notation P = 0 specific fluids can be found in the references . Viscosity is given in indicates that the low-pressure limiting value is given . The dif- units of μPa s; note that 1 μPa s = 10–5 poise . Substances are listed ference between the viscosity at 100 kPa and the limiting value is in the modified Hill order (see Introduction) . Viscosity in μPa s 100 K 200 K 300 K 400 K 500 K 600 K Ref. Air 7 .1 13 .3 18 .5 23 .1 27 .1 30 .8 1 Ar Argon (P = 0) 8 .1 15 .9 22 .7 28 .6 33 .9 38 .8 2, 3*, 4* BF3 Boron trifluoride 12 .3 17 .1 21 .7 26 .1 30 .2 5 ClH Hydrogen chloride 14 .6 19 .7 24 .3 5 F6S Sulfur hexafluoride (P = 0) 15 .3 19 .7 23 .8 27 .6 6 H2 Normal hydrogen (P = 0) 4 .1 6 .8 8 .9 10 .9 12 .8 14 .5 3*, 7 D2 Deuterium (P = 0) 5 .9 9 .6 12 .6 15 .4 17 .9 20 .3 8 H2O Water (P = 0) 9 .8 13 .4 17 .3 21 .4 9 D2O Deuterium oxide (P = 0) 10 .2 13 .7 17 .8 22 .0 10 H2S Hydrogen sulfide 12 .5 16 .9 21 .2 25 .4 11 H3N Ammonia 10 .2 14 .0 17 .9 21 .7 12 He Helium (P = 0) 9 .6 15 .1 19 .9 24 .3 28 .3 32 .2 13 Kr Krypton (P = 0) 17 .4 25 .5 32 .9 39 .6 45 .8 14 NO Nitric oxide 13 .8 19 .2 23 .8 28 .0 31 .9 5 N2 Nitrogen 7 .0 12 .9 17 .9 22 .2 26 .1 29 .6 1, 15* N2O Nitrous -

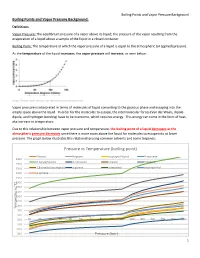

Pressure Vs Temperature (Boiling Point)

Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background: Definitions Vapor Pressure: The equilibrium pressure of a vapor above its liquid; the pressure of the vapor resulting from the evaporation of a liquid above a sample of the liquid in a closed container. Boiling Point: The temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid is equal to the atmospheric (or applied) pressure. As the temperature of the liquid increases, the vapor pressure will increase, as seen below: https://www.chem.purdue.edu/gchelp/liquids/vpress.html Vapor pressure is interpreted in terms of molecules of liquid converting to the gaseous phase and escaping into the empty space above the liquid. In order for the molecules to escape, the intermolecular forces (Van der Waals, dipole- dipole, and hydrogen bonding) have to be overcome, which requires energy. This energy can come in the form of heat, aka increase in temperature. Due to this relationship between vapor pressure and temperature, the boiling point of a liquid decreases as the atmospheric pressure decreases since there is more room above the liquid for molecules to escape into at lower pressure. The graph below illustrates this relationship using common solvents and some terpenes: Pressure vs Temperature (boiling point) Ethanol Heptane Isopropyl Alcohol B-myrcene 290.0 B-caryophyllene d-Limonene Linalool Pulegone 270.0 250.0 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) a-pinene a-terpineol terpineol-4-ol 230.0 p-cymene 210.0 190.0 170.0 150.0 130.0 110.0 90.0 Temperature (˚C) Temperature 70.0 50.0 30.0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 200 300 400 500 600 760 10.0 -10.0 -30.0 Pressure (torr) 1 Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background As a very general rule of thumb, the boiling point of many liquids will drop about 0.5˚C for a 10mmHg decrease in pressure when operating in the region of 760 mmHg (atmospheric pressure). -

It's Just a Phase!

BASIS Lesson Plan Lesson Name: It’s Just a Phase! Grade Level Connection(s) NGSS Standards: Grade 2, Physical Science FOSS CA Edition: Grade 3 Physical Science: Matter and Energy Module *Note to teachers: Detailed standards connections can be found at the end of this lesson plan. Teaser/Overview Properties of matter are illustrated through a series of demonstrations and hands-on explorations. Students will learn to identify solids, liquids, and gases. Water will be used to demonstrate the three phases. Students will learn about sublimation through a fun experiment with dry ice (solid CO2). Next, they will compare the propensity of several liquids to evaporate. Finally, they will learn about freezing and melting while making ice cream. Lesson Objectives ● Students will be able to identify the three states of matter (solid, liquid, gas) based on the relative properties of those states. ● Students will understand how to describe the transition from one phase to another (melting, freezing, evaporation, condensation, sublimation) ● Students will learn that matter can change phase when heat/energy is added or removed Vocabulary Words ● Solid: A phase of matter that is characterized by a resistance to change in shape and volume. ● Liquid: A phase of matter that is characterized by a resistance to change in volume; a liquid takes the shape of its container ● Gas: A phase of matter that can change shape and volume ● Phase change: Transformation from one phase of matter to another ● Melting: Transformation from a solid to a liquid ● Freezing: Transformation -

Specific Latent Heat

SPECIFIC LATENT HEAT The specific latent heat of a substance tells us how much energy is required to change 1 kg from a solid to a liquid (specific latent heat of fusion) or from a liquid to a gas (specific latent heat of vaporisation). �����푦 (��) 퐸 ����������푐 ������� ℎ���� �� ������� �� = (��⁄��) = 푓 � ����� (��) �����푦 = ����������푐 ������� ℎ���� �� 퐸 = ��푓 × � ������� × ����� ����� 퐸 � = �� 푦 푓 ����� = ����������푐 ������� ℎ���� �� ������� WORKED EXAMPLE QUESTION 398 J of energy is needed to turn 500 g of liquid nitrogen into at gas at-196°C. Calculate the specific latent heat of vaporisation of nitrogen. ANSWER Step 1: Write down what you know, and E = 99500 J what you want to know. m = 500 g = 0.5 kg L = ? v Step 2: Use the triangle to decide how to 퐸 ��푣 = find the answer - the specific latent heat � of vaporisation. 99500 퐽 퐿 = 0.5 �� = 199 000 ��⁄�� Step 3: Use the figures given to work out 푣 the answer. The specific latent heat of vaporisation of nitrogen in 199 000 J/kg (199 kJ/kg) Questions 1. Calculate the specific latent heat of fusion if: a. 28 000 J is supplied to turn 2 kg of solid oxygen into a liquid at -219°C 14 000 J/kg or 14 kJ/kg b. 183 600 J is supplied to turn 3.4 kg of solid sulphur into a liquid at 115°C 54 000 J/kg or 54 kJ/kg c. 6600 J is supplied to turn 600g of solid mercury into a liquid at -39°C 11 000 J/kg or 11 kJ/kg d. -

Chapter 3 3.4-2 the Compressibility Factor Equation of State

Chapter 3 3.4-2 The Compressibility Factor Equation of State The dimensionless compressibility factor, Z, for a gaseous species is defined as the ratio pv Z = (3.4-1) RT If the gas behaves ideally Z = 1. The extent to which Z differs from 1 is a measure of the extent to which the gas is behaving nonideally. The compressibility can be determined from experimental data where Z is plotted versus a dimensionless reduced pressure pR and reduced temperature TR, defined as pR = p/pc and TR = T/Tc In these expressions, pc and Tc denote the critical pressure and temperature, respectively. A generalized compressibility chart of the form Z = f(pR, TR) is shown in Figure 3.4-1 for 10 different gases. The solid lines represent the best curves fitted to the data. Figure 3.4-1 Generalized compressibility chart for various gases10. It can be seen from Figure 3.4-1 that the value of Z tends to unity for all temperatures as pressure approach zero and Z also approaches unity for all pressure at very high temperature. If the p, v, and T data are available in table format or computer software then you should not use the generalized compressibility chart to evaluate p, v, and T since using Z is just another approximation to the real data. 10 Moran, M. J. and Shapiro H. N., Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics, Wiley, 2008, pg. 112 3-19 Example 3.4-2 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A closed, rigid tank filled with water vapor, initially at 20 MPa, 520oC, is cooled until its temperature reaches 400oC. -

Thermal Properties of Petroleum Products

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF STANDARDS THERMAL PROPERTIES OF PETROLEUM PRODUCTS MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATION OF THE BUREAU OF STANDARDS, No. 97 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE R. P. LAMONT, Secretary BUREAU OF STANDARDS GEORGE K. BURGESS, Director MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATION No. 97 THERMAL PROPERTIES OF PETROLEUM PRODUCTS NOVEMBER 9, 1929 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1929 F<ir isale by tfttf^uperintendent of Dotmrtients, Washington, D. C. - - - Price IS cants THERMAL PROPERTIES OF PETROLEUM PRODUCTS By C. S. Cragoe ABSTRACT Various thermal properties of petroleum products are given in numerous tables which embody the results of a critical study of the data in the literature, together with unpublished data obtained at the Bureau of Standards. The tables contain what appear to be the most reliable values at present available. The experimental basis for each table, and the agreement of the tabulated values with experimental results, are given. Accompanying each table is a statement regarding the esti- mated accuracy of the data and a practical example of the use of the data. The tables have been prepared in forms convenient for use in engineering. CONTENTS Page I. Introduction 1 II. Fundamental units and constants 2 III. Thermal expansion t 4 1. Thermal expansion of petroleum asphalts and fluxes 6 2. Thermal expansion of volatile petroleum liquids 8 3. Thermal expansion of gasoline-benzol mixtures 10 IV. Heats of combustion : 14 1. Heats of combustion of crude oils, fuel oils, and kerosenes 16 2. Heats of combustion of volatile petroleum products 18 3. Heats of combustion of gasoline-benzol mixtures 20 V. -

Lecture 11. Surface Evaporation and Soil Moisture (Garratt 5.3) in This

Atm S 547 Boundary Layer Meteorology Bretherton Lecture 11. Surface evaporation and soil moisture (Garratt 5.3) In this lecture… • Partitioning between sensible and latent heat fluxes over moist and vegetated surfaces • Vertical movement of soil moisture • Land surface models Evaporation from moist surfaces The partitioning of the surface turbulent energy flux into sensible vs. latent heat flux is very important to the boundary layer development. Over ocean, SST varies relatively slowly and bulk formulas are useful, but over land, the surface temperature and humidity depend on interactions of the BL and the surface. How, then, can the partitioning be predicted? For saturated ideal surfaces (such as saturated soil or wet vegetation), this is relatively straight- forward. Suppose that the surface temperature is T0. Then the surface mixing ratio is its saturation value q*(T0). Let z1 denote a measurement height within the surface layer (e. g. 2 m or 10 m), at which the temperature and humidity are T1 and q1. The stability is characterized by an Obhukov length L. The roughness length and thermal roughness lengths are z0 and zT. Then Monin-Obuhkov theory implies that the sensible and latent heat fluxes are HS = ρLvCHV1 (T0 - T1), HL = ρLvCHV1 (q0 - q1), where CH = fn(V1, z1, z0, zT, L)" We can eliminate T0 using a linearized version of the Clausius-Clapeyron equations: q0 - q*(T1) = (dq*/dT)R(T0 - T1), (R indicates a reference temp. near (T0 + T1)/2) HL = s*HS +!LCHV1(q*(T1) - q1), (11.1) s* = (L/cp)(dq*/dT)R (= 0.7 at 273 K, 3.3 at 300 K) This equation expresses latent heat flux in terms of sensible heat flux and the saturation deficit at the measurement level. -

Changes in State and Latent Heat

Physical State/Latent Heat Changes in State and Latent Heat Physical States of Water Latent Heat Physical States of Water The three physical states of matter that we normally encounter are solid, liquid, and gas. Water can exist in all three physical states at ordinary temperatures on the Earth's surface. When water is in the vapor state, as a gas, the water molecules are not bonded to each other. They float around as single molecules. When water is in the liquid state, some of the molecules bond to each other with hydrogen bonds. The bonds break and re-form continually. When water is in the solid state, as ice, the molecules are bonded to each other in a solid crystalline structure. This structure is six- sided, with each molecule of water connected to four others with hydrogen bonds. Because of the way the crystal is arranged, there is actually more empty space between the molecules than there is in liquid water, so ice is less dense. That is why ice floats. Latent Heat Each time water changes physical state, energy is involved. In the vapor state, the water molecules are very energetic. The molecules are not bonded with each other, but move around as single molecules. Water vapor is invisible to us, but we can feel its effect to some extent, and water vapor in the atmosphere is a very important http://daphne.palomar.edu/jthorngren/latent.htm (1 of 4) [4/9/04 5:30:18 PM] Physical State/Latent Heat factor in weather and climate. In the liquid state, the individual molecules have less energy, and some bonds form, break, then re-form. -

Recap: First Law of Thermodynamics Joule: 4.19 J of Work Raised 1 Gram Water by 1 ºC

Recap: First Law of Thermodynamics Joule: 4.19 J of work raised 1 gram water by 1 ºC. This implies 4.19 J of work is equivalent to 1 calorie of heat. • If energy is added to a system either as work or as heat, the internal energy is equal to the net amount of heat and work transferred. • This could be manifest as an increase in temperature or as a “change of state” of the body. • First Law definition: The increase in internal energy of a system is equal to the amount of heat added minus the work done by the system. ΔU = increase in internal energy ΔU = Q - W Q = heat W = work done by system Note: Work done on a system increases ΔU. Work done by system decreases ΔU. Change of State & Energy Transfer First law of thermodynamics shows how the internal energy of a system can be raised by adding heat or by doing work on the system. U -W ΔU = Q – W Q Internal Energy (U) is sum of kinetic and potential energies of atoms /molecules comprising system and a change in U can result in a: - change on temperature - change in state (or phase). • A change in state results in a physical change in structure. Melting or Freezing: • Melting occurs when a solid is transformed into a liquid by the addition of thermal energy. • Common wisdom in 1700’s was that addition of heat would cause temperature rise accompanied by melting. • Joseph Black (18th century) established experimentally that: “When a solid is warmed to its melting point, the addition of heat results in the gradual and complete liquefaction at that fixed temperature.” • i.e. -

Safety Advice. Cryogenic Liquefied Gases

Safety advice. Cryogenic liquefied gases. Properties Cryogenic Liquefied Gases are also known as Refrigerated Liquefied Gases or Deeply Refrigerated Gases and are commonly called Cryogenic Liquids. Cryogenic Gases are cryogenic liquids that have been vaporised and may still be at a low temperature. Cryogenic liquids are used for their low temperature properties or to allow larger quantities to be stored or transported. They are extremely cold, with boiling points below -150°C (-238°F). Carbon dioxide and Nitrous oxide, which both have higher boiling points, are sometimes included in this category. In the table you may find some data related to the most common Cryogenic Gases. Helium Hydrogen Nitrogen Argon Oxygen LNG Nitrous Carbon Oxide Dioxide Chemical symbol He H2 N2 Ar O2 CH4 N2O CO2 Boiling point at 1013 mbar [°C] -269 -253 -196 -186 -183 -161 -88.5 -78.5** Density of the liquid at 1013 mbar [kg/l] 0.124 0.071 0.808 1.40 1.142 0.42 1.2225 1.1806 3 Density of the gas at 15°C, 1013 mbar [kg/m ] 0.169 0.085 1.18 1.69 1.35 0.68 3.16 1.87 Relative density (air=1) at 15°C, 1013 mbar * 0.14 0.07 0.95 1.38 1.09 0.60 1.40 1.52 Gas quantity vaporized from 1 litre liquid [l] 748 844 691 835 853 630 662 845 Flammability range n.a. 4%–75% n.a. n.a. n.a. 4.4%–15% n.a. n.a. Notes: *All the above gases are heavier than air at their boiling point; **Sublimation point (where it exists as a solid) Linde AG Gases Division, Carl-von-Linde-Strasse 25, 85716 Unterschleissheim, Germany Phone +49.89.31001-0, [email protected], www.linde-gas.com 0113 – SA04 LCS0113 Disclaimer: The Linde Group has no control whatsoever as regards performance or non-performance, misinterpretation, proper or improper use of any information or suggestions contained in this instruction by any person or entity and The Linde Group expressly disclaims any liability in connection thereto. -

Lecture 8 Phases, Evaporation & Latent Heat

LECTURE 8 PHASES, EVAPORATION & LATENT HEAT Lecture Instructor: Kazumi Tolich Lecture 8 2 ¨ Reading chapter 17.4 to 17.5 ¤ Phase equilibrium ¤ Evaporation ¤ Latent heats n Latent heat of fusion n Latent heat of vaporization n Latent heat of sublimation Phase equilibrium & vapor-pressure curve 3 ¨ If a substance has two or more phases that coexist in a steady and stable fashion, the substance is in phase equilibrium. ¨ The pressure of the gas when equilibrium is reached is called equilibrium vapor pressure. ¨ A plot of the equilibrium vapor pressure versus temperature is called vapor-pressure curve. ¨ A liquid boils at the temperature at which its vapor pressure equals the external pressure. Phase diagram 4 ¨ A fusion curve indicates where the solid and liquid phases are in equilibrium. ¨ A sublimation curve indicates where the solid and gas phases are in equilibrium. ¨ A plot showing a vapor-pressure curve, a fusion curve, and a sublimation curve is called a phase diagram. ¨ The vapor-pressure curve comes to an end at the critical point. Beyond the critical point, there is no distinction between liquid and gas. ¨ At triple point, all three phases, solid, liquid, and gas, are in equilibrium. ¤ In water, the triple point occur at T = 273.16 K and P = 611.2 Pa. Quiz: 1 5 ¨ In most substance, as the pressure increases, the melting temperature of the substance also increases because a solid is denser than the corresponding liquid. But in water, ice is less dense than liquid water. Does the fusion curve of water have a positive or negative slope? A.