A Comparative Study of Two Small & Remote Urban Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cerro Torre (Daniel Joll)

No. 804, March 2017 Vertigo April Section Night – Cerro Torre (Daniel Joll) Newsletter of the New Zealand Alpine Club - Wellington Section www.facebook.com/nzacwellington Twitter @NZACWellington Section News April Section Night Daniel Joll returns to Wellington for our April section night kicking off at 6pm on 1 March at the Southern Cross on Abel Smith Street. Dan will take us on the Ragni route of Cerro Torre which he climbed in the last week of February. He’ll also give us a quick summary of his recent NZ Alpine Team trip to Canada. May Section Night South Island traverse 2016/17 Alexis Belton was a member of the team who carried out a South Island traverse recently. Alexis will show a presentation and talk about the team’s 4 month traverse of the South Island of New Zealand from Cape Farewell to Foveaux Strait. Lake Poteriteri Come hear about the highs and lows of life on the tour in the mountains of the South Island during the wettest summers in years. Travelling mostly by foot, but also by bike, kayak and packraft, our route took us through the undervalued splendours Kahurangi, the mighty South Alps and the depths of south-western Fiordland. Frew Saddle Please don’t forget the koha for section night – there’ll be an ice bucket at the entry door for that purpose. ☺ Page 2 Chairs Report March 2017 I’ve recently received the NZAC membership survey results and you might be interested in the following. • Wellington Section had 472 members at last count. • We get between 30 and 60 members at our monthly section nights and anywhere from 4 to 20 members on section trips. -

Ruapehu College

RUAPEHU COLLEGE Seek further knowledge Newsletter Ruapehu College, at the heart of our community and the college of choice, making a mountain of difference in learning and for life. Principal: Kim Basse Newsletter 15—23 October 2018 Email : [email protected] Phone: 06 3858398 Help Tui Wikohika on his journey to compete at the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics In Snowboard Slopestyle and Big Air. There has been a Pledge Me page set up for donations https://www.pledgeme.co.nz/projects/5855-help-tui-wikohika-on-his-journey-to-compete-at-the-2022-beijing- winter-olympics-in-snowboard-slopestyle-and-big-air?fbclid=IwAR1FEac1W9- 3IhkmqpWwXDXQqpqh0qCiGByR3R5PtrqmH4BjCSNAAySdfn0 Tui Wikohika is a 14 year old snowboarder from Raetihi NZ, who has dreams of making the NZ Olympic team in freestyle snowboarding. Tui's journey towards his dream has involved many hours of training, hard work and sacrifice. Tui's aspirations and vision for the sport has seen him working part time since he was at primary school and after training to help fund his travel to training camps and competitions around NZ. Tui is currently ranked 2nd in NZ for U16 boys snowboarding after a successful nationals campaign. Tui aims to travel to Colorado and Canada over the 2019 NZ summer to train and compete in world class facilities against American and Canadian athletes. This will help prepare Tui for a big NZ Winter season next year where he hopes to compete on the world junior rookie tour and all FIS sanctioned events. These events will give him a world ranking where he can track his progress against international riders. -

Visitor Perceptions of Natural Hazards at Whakapapa and Turoa Ski Areas, Mt Ruapehu

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Visitor Perceptions of Natural Hazards at Whakapapa and Turoa Ski Areas, Mt Ruapehu A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Geography at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand. Celeste N. Milnes 2010 ii Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of M.Phil. (Geography) Visitor Perceptions of Natural Hazards at Whakapapa and Turoa Ski Areas, Mt Ruapehu By C. N. Milnes Whakapapa and Turoa are ski areas located on the active volcano Mt Ruapehu, in the Central North Island of New Zealand. Mt Ruapehu is located within Tongariro National Park, one of the 14 National Parks administered by the Department of Conservation (DoC). Visitors to Whakapapa and Turoa ski areas encounter an array of hazards, including icy slopes, ragged cliffs and drop-offs, and thousands of other mountain users. Hazards unique to Whakapapa and Turoa include the threat to human safety from lahars, ash falls, pyroclastic flows, erosion, rock falls, crevassing and ballistic bombs due to the active volcanic nature of this mountain. Managing these hazards at Mt Ruapehu is complex due to the number of factors involved. This dynamic site hosts visitors who are moderately experienced and prepared, but may be complacent about the danger to personal safety within these areas. -

New Zealand National Climate Summary 2011: a Year of Extremes

NIWA MEDIA RELEASE: 12 JANUARY 2012 New Zealand national climate summary 2011: A year of extremes The year 2011 will be remembered as one of extremes. Sub-tropical lows during January produced record-breaking rainfalls. The country melted under exceptional heat for the first half of February. Winter arrived extremely late – May was the warmest on record, and June was the 3 rd -warmest experienced. In contrast, two significant snowfall events in late July and mid-August affected large areas of the country. A polar blast during 24-26 July delivered a bitterly cold air mass over the country. Snowfall was heavy and to low levels over Canterbury, the Kaikoura Ranges, the Richmond, Tararua and Rimutaka Ranges, the Central Plateau, and around Mt Egmont. Brief dustings of snow were also reported in the ranges of Motueka and Northland. In mid-August, a second polar outbreak brought heavy snow to unusually low levels across eastern and alpine areas of the South Island, as well as to suburban Wellington. Snow also fell across the lower North Island, with flurries in unusual locations further north, such as Auckland and Northland. Numerous August (as well as all-time) low temperature records were broken between 14 – 17 August. And torrential rain caused a State of Emergency to be declared in Nelson on 14 December, following record- breaking rainfall, widespread flooding and land slips. Annual mean sea level pressures were much higher than usual well to the east of the North Island in 2011, producing more northeasterly winds than usual over northern and central New Zealand. -

The New Zealand Police Ski Club Information Site

WELCOME TO THE NEW ZEALAND POLICE SKI CLUB INFORMATION SITE Established in 1986, the NZ Police Ski Club Inc was formed when a group of enthusiastic Police members came together with a common goal of snow, sun and fun. In 1992 the Club purchased an existing property situated at 35 Queen Street, Raetihi that has over 40 beds in 12 rooms. It has a spacious living area, cooking facilities, a drying room and on-site custodians. NZPSC, 35 Queen Street, Raetihi 4632, New Zealand Ph/Fax 06 385 4003 A/hours 027 276 4609 email [email protected] Raetihi is just 11 kilometres from Ohakune, the North Island’s bustling ski town at the south-western base of the mighty Mt Ruapehu, New Zealand’s largest and active volcano. On this side of the mountain can be found the Turoa ski field. Turoa ski field boasts 500 hectares of in boundary terrain. The Whakapapa ski field is on the north-west side of the mountain and is about 56 kilometres from Raetihi to the top car park at the Iwikau Village. Whakapapa has 550 hectares of in boundary terrain. You don't need to be a member of the Police to join as a Ski Club member or to stay at the Club! NZPSC, 35 Queen Street, Raetihi 4632, New Zealand Ph/Fax 06 385 4003 A/hours 027 276 4609 email [email protected] More Stuff!! The Club hosts the New Zealand Police Association Ski Champs at Mt Ruapehu and in South Island ski fields on behalf of the Police Council of Sport and the Police Association. -

Economic Recovery Strategy

Manawatū-Whanganui Region (Post-COVID-19) Economic Recovery Strategy “WHAT” Survive Short-term Keep people in their jobs; keep businesses alive • Cash Support for businesses Survive 0-6 months 3 • Advice Wage subsidy 3 Keep people in work; provide work for businesses Revive Medium-term Shovel-ready, • Jobs Revive suffering from the COVID downturn 6-12 months job-rich infrastructure Phases Work • Businesses projects Create new, valuable jobs. Build vigorous, productive Plans Thrive Long-term Big Regional Thrive • Resilience businesses. Achieve ambitious regional goals. 12+ months Development Projects • Future-proof Priority Projects Box 2 – Project Detail High $ Estimated Central NZ Projects Impact Food O2NL Investment Jobs distribution Central NZ distribution – Regional Freight Ring Road and HQ Ruapehu c. $3-3.5 Freight efficiency and connectivity across Central North Island Freight Hub - significant development SkillsSkills & & Te Ahu a billion c. 350 for central New Zealand and ports, reduced freight Tourism project: new KiwiRail distribution hub, new regional freight Talent (public and construction costs, reduced carbon emissions, major wealth Talent Turanga ring road commercial) and job creation Shovel-ready Highway Lead: PNCC – Heather Shotter Skills & Talent Projects Critical north-south connection, freight SH1 – Otaki to North of Levin (O2NL) – major new alignment c. 300 over 5 Te Puwaha - c. $800 efficiency, safety and hazard resilience, major 1 2 for SH1 around Levin years for million wealth and job creation through processing, Whanganui Lead: Horowhenua District Council – David Clapperton construction Impact manufacturing and logistics growth Marton Port axis Manawatū Ruapehu Tourism - increasing Tourism revenue from $180m Facilities and tourism services development Rail Hub c. -

Ōwhango School Panui

ŌWHANGO SCHOOL PANUI Working Together to Achieve Our Very Best Me Mahi Tahi Tatou Kia Whiwhi Mai Nga Mea Pai Rawa Phone 07 895 4823 Cell 027 895 4823 www.owhangoschool.co.nz Email: [email protected] [email protected] 5/2021 17th March 2021 THOUGHT OF THE WEEK / WHAKATAUKĪ are also building up great balance skills on their “Pearls lie not on the seashore. If you desire one chosen wheel-based toy. you must dive for it.” Chinese proverb It is an asset that will have ongoing rewards for the lifetime of the track, which should be long as it is DATES TO NOTE well engineered. 18 March Inter-school Swimming 19 March Golf- mini golf at Schnapps 23 March PTA Hui 3:15 Golf 26 March Bike Day 29 & 30 March Zero Waste 30 March 1:30pm Duffy Role Model 31 March Junior Hockey skills and fun night 1 April Tech. Day for Year 7&8 Fri 2- Tue 6 April Easter Break - No School 7 April Hockey competition games begin Golf 9 April Inter-school Softball Tournament 10 April Saturday: Netball Grading Day 12-15 April Footsteps Dance Lessons Tech. Day for Year 7&8 End of Term Assembly- Dance 15 April The original inspiration for our scooter track. Performance in the Hall BoT Hui 7pm 16 April Last Day of Term One 17 April Saturday: Netball Grading Day 3 May First Day of Term Two PRINCIPAL’S MESSAGE A final thanks to everyone who has helped to make our scooter track a reality. Our third and final working bee on Saturday was again well attended, which meant all the boxing and waste concrete was removed, soil placed around the track, and grass seed sown. -

Manawatu -Wanganui

Venue No Venue Name Venue Physical Address 98 FOXTON RETURNED SERVICES ASSOCIATION 1 EASTON STREET,FOXTON, MANAWATU 4814,NEW ZEALAND 136 TAUMARUNUI COSMOPOLITAN CLUB CORNER KATARINA AND MIRIAMA STREETS,TAUMARUNUI CENTRAL, TAUMARUNUI 3920,NEW ZEALAND 192 CASTLECLIFF CLUB INC 4 TENNYSON STREET,CASTLECLIFF, WANGANUI DISTRICT 4501,NEW ZEALAND 222 THE OFFICE 514-516 MAIN STREET EAST, PALMERSTON NORTH CENTRAL, PALMERSTON NORTH 5301 223 WILLOW PARK TAVERN 820 TREMAINE AVENUE, PALMERSTON NORTH CENTRAL, PALMERSTON NORTH 5301 225 THE COBB 522-532 MAIN STREET EAST, PALMERSTON NORTH CENTRAL, PALMERSTON NORTH 5301 261 TAUMARUNUI RSA CLUB 10 MARAE STREET,TAUMARUNUI CENTRAL, TAUMARUNUI 3946,NEW ZEALAND 272 DANNEVIRKE SERVICES AND CITIZENS CLUB 1 PRINCESS STREET, DANNEVIRKE, MANAWATU 5491 293 Ohakune Tavern 66-72 CLYDE STREET,OHAKUNE, MANAWATU 4625,NEW ZEALAND 308 THE EMPIRE HOTEL 8 STAFFORD STREET, FEILDING, MANAWATU 5600 347 WANGANUI EAST CLUB 101 WAKEFIELD STREET, WANGANUI, WANGANUI DISTRICT 4540 356 TARARUA CLUB 15 TARARUA STREET, PAHIATUA, MANAWATU 5470 365 OHAKUNE CLUB 71 GOLDFINCH STREET, OHAKUNE, MANAWATU 5461 389 ALBERT SPORTS BAR 692-700 MAIN STREET EAST, PALMERSTON NORTH CENTRAL, PALMERSTON NORTH 5301 394 STELLAR BAR 2 VICTORIA STREET, WANGANUI, WANGANUI DISTRICT 4540 395 FATBOYZ BAR COBB AND CO CORNER DURHAM AND OXFORD STREETS, LEVIN, MANAWATU 5500 410 ASHHURST MEMORIAL RSA 74 CAMBRIDGE AVENUE,ASHHURST, MANAWATU 4847,NEW ZEALAND 431 ST JOHN'S CLUB 158 GLASGOW STREET,WANGANUI, WANGANUI DISTRICT 4500,NEW ZEALAND 439 LEVIN COSMOPOLITAN CLUB 47-51 -

42 Traverse — NZ Walking Access Commission Ara Hīkoi Aotearoa

9/25/2021 42 Traverse — NZ Walking Access Commission Ara Hīkoi Aotearoa 42 Traverse Walking Mountain Biking Horse Riding Difculty Medium Length 71.5 km Journey Time 4-7 hours mountain biking, 3-4 days walking Regions Waikato , Manawatū-Whanganui Sub-Region Ruapehu Part of Collections https://www.walkingaccess.govt.nz/track/42-traverse/pdfPreview 1/4 9/25/2021 42 Traverse — NZ Walking Access Commission Ara Hīkoi Aotearoa Te Araroa - New Zealand's Trail , Te Araroa - North Island Track maintained by Te Araroa Trail Trust From Hākiaha Street (SH4) in Taumarunui, head south (Turaki Street and Morero Terrace) to cross the Whanganui River and get onto Hikumutu Road for a long but pleasant walk through the countryside. Follow Hikumutu Road through the small settlement of Hikumutu, past a brief encounter with the Whanganui River, then east to Ōwhango. You'll join Kawautahi Road just before you get to Ōwhango, follow that east 1km to SH4. Then walk north 200m on SH4 and turn right/east into Omatane Road on the southern edge of Ōwhango. Follow Omatane Road, Onga Street and Whakapapa Bush Road to the start of the 42 Traverse. It is 27km from Hākiaha Street in Taumarunui to Ōwhango. 42 Traverse (incl. Waione/Cokers Track) - 35km / 1.5 days This track follows the 42 Traverse four wheel drive road for the rst 22km - in wet conditions this can be very muddy/slippery. This branches off along the Waione/Cokers DOC track, then on to Access Road #3 for a short while before a deviation northeast past the historical landmark, Te Pōrere Redoubt, before joining SH47. -

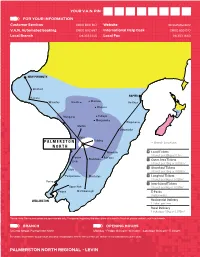

PALMERSTON NORTH REGIONAL - LEVIN Customers Can Check If an Address Is Considered Rural Or Residential by Using the ‘Address Checker’ Tool on Our Website

LOCAL SERVICES YOUR V..A NI. P N FORYOUR INFORMATION LOCAL ANDREGIONAL - SAME DAY SERVICES Customer Services Website V.A.N.Automated booking International Help Desk Local Branch 06 353 1445 Local Fax 06 353 1660 AUCKLAND NEW PLYMOUTH Stratford NAPIER Hawera Waverley Raetihi Ohakune Hastings Branch Locations Waiouru Local Tickets Wanganui Taihape 1 ticket per 25kg or 0.1m3 Mangaweka Outer Area Tickets Waipukurau 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m3 Marton Shorthaul Tickets Dannevirke 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m3 Longhaul Tickets Bulls Feilding 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025mP ALMERSTON3 Branch Locations Inter-Island Tickets NORTH 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025m3 Woodville Local Tickets E-Packs 1 ticket per 25kg or 0.1m3 (Nationwide-no boundaries) Foxton Pahiatua Eketahuna Outer Area Tickets Levin 3 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m Shorthaul Tickets Otaki 3 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m Paraparaumu Masterton Longhaul Tickets h 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025m3 Porirua Inter-Island Tickets Upper Hutt 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025m3 Petone Martinborough E -Packs (Nationwide) WELLINGTON Residential Delivery 1 ticket per item Rural Delivery 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.075m3 Please Note: Above zone areas are approximate only, For queries regarding the exact zone of a specific location, please contact your local branch. BRANCH OPENINGHOURS OVERNIGHT SERVICES 12 Cook Street, Palmerston North Monday - Friday: 8.00am-6.00pm Saturday: 8.00am - 11.00am Your last pick-up time is: For details on where to buy product and drop off packages, refer to the ‘Contact Us’ section of our website nzcouriers.co.nz Overnight by 9.30am to main business centres. -

Mahere Waka Whenua Ā-Rohe Regional Land Transport Plan 2021 - 2031

Mahere Waka Whenua ā-rohe Regional Land Transport Plan 2021 - 2031 1 Mahere Waka Whenua ā-rohe Regional Land Transport Plan - 2021-2031 AUTHOR SERVICE CENTRES Horizons Regional Transport Committee, Kairanga which includes: Cnr Rongotea and Kairanga -Bunnythorpe Roads, Horizons Regional Council Palmerston North Marton Horowhenua District Council 19 Hammond Street Palmerston North City Council Taumarunui Manawatū District Council 34 Maata Street Whanganui District Council REGIONAL HOUSES Tararua District Council Palmerston North Rangitīkei District Council 11-15 Victoria Avenue Ruapehu District Council Whanganui 181 Guyton Street Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency New Zealand Police (advisory member) DEPOTS KiwiRail (advisory member) Taihape Torere Road, Ohotu Road Transport Association NZ (advisory member) Woodville AA road users (advisory member) 116 Vogel Street Active transport/Public transport representative (advisory member) CONTACT 24 hr freephone 0508 800 800 [email protected] www.horizons.govt.nz Report No: 2021/EXT/1720 POSTAL ADDRESS ISBN 978-1-99-000954-9 Horizons Regional Council, Private Bag 11025, Manawatū Mail Centre, Palmerston North 4442 Rārangi kaupapa i Table of contents He Mihi Nā Te Heamana - Introduction From The Chair 02 Rautaki Whakamua - Strategic Context And Direction 03 1 He kupu whakataki - Introduction 04 1.1 Te whāinga o te Mahere / Purpose of the Plan 05 Te hononga o te Mahere Waka Whenua ā-Rohe ki ētahi atu rautaki - Relationship of the Regional Land Transport Plan to other 1.2 06 strategic documents 2 Horopaki -

“The Grand North Island Railtour”

THE GLENBROOK VINTAGE RAILWAY CHARITABLE TRUST PO Box 454, Waiuku Auckland 2341 Main Line Excursion train operator for The Railway Enthusiasts’ Society Inc, Auckland “The Grand North Island Railtour” - 2020 Trip #2001 ITINERARIES Issued 19.08.20 These Itineraries are subject to variation / change for train scheduling alterations or other circumstances. An updated Final Itinerary will be issued a week prior to the Railtour commencing. ‘A-1’ (Southbound) - Eight Days, (7 nights), Pukekohe to Wellington Day 1: Monday 12 Oct: (Auckland) to Pukekohe to Rotorua 07.00: (Connecting service) - Depart Britomart on AT’s Southern Line train for Papakura and Pukekohe arriving at 08.49. GVR’s Railtour Leader will be on board to act as group escort from Britomart. 09.00: - Depart Pukekohe for Tokoroa direct on our special GVR train. 09.37: - Te Kauwhata passenger pick up (if required) 10.45: - Arrive Hamilton - passenger pick up. 12.03: - Arrive Matamata - (special charter group passenger drop off) Free time for purchasing lunch from (adjacent) main street shops. 13.00: - Depart Matamata on our special GVR train. Planned Photo stop scheduled near Putaruru 14.30 - Arrive Tokoroa. Change to chartered road coach for transfer direct to Rotorua, arriving around 15.30. Group check in at hotel. Remainder of day and evening free in Rotorua! Accommodation: Rotorua Day 2: Tue 13 Oct: - Free Day in Rotorua! From 07.00 Breakfast at hotel. Optional Activities: Rotorua District road coach tour 09.00: - BRIEFING in hotel lobby. Board our chartered road coach for a leisurely day visiting local attractions and places of interest.