Genetics and Variation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gardenergardener

TheThe AmericanAmerican GARDENERGARDENER TheThe MagazineMagazine ofof thethe AAmericanmerican HorticulturalHorticultural SocietySociety January/February 2005 new plants for 2005 Native Fruits for the Edible Landscape Wildlife-Friendly Gardening Chanticleer: A Jewel of a Garden The Do’s andand Don’tsDon’ts ofof Planting Under Trees contents Volume 84, Number 1 . January / February 2005 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 5 NOTES FROM RIVER FARM 6 MEMBERS’ FORUM 8 NEWS FROM AHS AHS’s restored White House gates to be centerpiece of Philadelphia Flower Show entrance exhibit, The Growing Connection featured during United Nations World Food Day events, Utah city’s volunteer efforts during America in Bloom competition earned AHS Community Involvement Award, Great Southern Tree Conference is newest AHS partner. 14 AHS PARTNERS IN PROFILE page 22 The Care of Trees brings passion and professionalism to arboriculture. 44 GARDENING BY DESIGN 16 NEW FOR 2005 BY RITA PELCZAR Forget plants—dream of design. A preview of the exciting and intriguing new plant introductions. 46 GARDENER’S NOTEBOOK Gardening trends in 2005, All-America 22 CHANTICLEER BY CAROLE OTTESEN Selections winners, Lenten rose is perennial of the year, wildlife This Philadephia-area garden is being hailed as one of the finest gardening courses small public gardens in America. online, new Cornell Web site allows rating of 26 NATIVE FRUITS BY LEE REICH vegetable varieties, Add beauty and flavor to your landscape with carefree natives like Florida gardens recover from hurricane damage, page 46 beach plum, persimmon, pawpaw, and clove currant. gardeners can help with national bird count. 31 TURNING A GARDEN INTO A COMMUNITY BY JOANNE WOLFE 50 In this first in a series of articles on habitat gardening, learn how to GROWING THE FUTURE create an environment that benefits both gardener and wildlife. -

October 1961 , Volume 40, Number 4 305

TIIE .A:M:ERICA.N ~GAZINE AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY A union of the Amej'ican HOTticu~tural Society and the AmeTican HOTticultural Council 1600 BLADENSBURG ROAD, NORTHEAST. WASHINGTON 2, D. C. For United Horticulture *** to accumulate, increase, and disseminate horticultural intOTmation B. Y. MORRISON, Editor Directors Terms Expiring 1961 JAMES R. HARLOW, Managing Editor STUART M. ARMSTRONG Maryland Editorial Committee JOH N L. CREECH . Maryland W. H . HODGE, Chairman WILLIAM H. FREDERICK, JR. Delaware JOH N L. CREECH FRANCIS PATTESON-KNIGHT FREDERIC P. LEE Virginia DONALD WYMAN CONRAD B. LINK Massachusetts CURTIS MAY T erms Expiring 1962 FREDERICK G . MEYER FREDERIC P. LEE WILBUR H . YOUNGMAN Maryland HENRY T . SKINNER District of Columbia OfJiceTS GEORGE H. SPALDING California PRESIDENT RICHARD P. WHITE DONAlJD WYMAN Distj'ict of Columbia Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts ANNE WERTSNER WOOD Pennsylvania FIRST VICE· PRESIDENT Ternu Expiring 1963 ALBERT J . IRVING New l'm'k, New York GRETCHEN HARSHBARGER Iowa SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT MARY W. M. HAKES Maryland ANNE WERTSNER W ' OOD FREDERIC HEUTTE Swarthmore, Pennsylvania Virginia W . H. HODGE SECRETARY-TREASURER OLIVE E. WEATHERELL ALBERT J . IRVING Washington, D, C. New York The Ame"ican Horticultural Magazine is the official publication of the American Horticultural Society and is issued four times a year during the quarters commencing with January, April, July and October. It is devoted to the dissemination of knowledge in the science and art of growing ornamental plants, fruits, vegetables, and related subjects. Original papers increasing the historical, varietal, and cultural knowledges of plant materials of economic and aesthetic importance are welcomed and will be published as early as possible. -

A Rare Affair an Auction of Exceptional Offerings

A Rare Affair An Auction of Exceptional Offerings MAY 29, 2015 Chicago Botanic Garden CATALOGUE AUCTION RULES AND PROCEDURES The Chicago Botanic Garden strives CHECKOUT to provide accurate information and PROCEDURES healthy plants. Because many auction Silent Auction results will be posted in items are donated, neither the auctioneer the cashier area in the East Greenhouse nor the Chicago Botanic Garden can Gallery at 9:15 p.m. Live auction results guarantee the accuracy of descriptions, will be posted at regular intervals during condition of property or availability. the live auction. Cash, check, Discover, All property is sold as is, and all sales MasterCard and Visa will be accepted. are final. Volunteers will be available to assist you with checkout, and help transport your SILENT AUCTION purchases to the valet area. All purchases Each item, or group of items, has a must be paid for at the event. bid sheet marked with its name and lot number. Starting bid and minimum SATURDAY MORNING bid increments appear at the top of the PICK-UP sheet. Each bid must be an increase over Plants may be picked up at the Chicago the previous bid by at least the stated Botanic Garden between 9 and 11 a.m. increment for the item. To bid, clearly on Saturday, May 30. Please notify the write the paddle number assigned to Gatehouse attendant that you are picking you, your last name, and the amount up your plant purchases and ask for you wish to bid. Illegible or incorrect directions to the Buehler parking lot. If bid entries will be disqualified. -

Fall Thalweg.Indd

thethe Fall 2011 Watershed Stewardship Program Volume 8 Issue 4 Pick It Up Pals Cobb County Board of Commissioners Tim Lee Program Chairman Every ti me it rains, water runs off roof tops, lawns, driveways, parking lots, and streets picking up pollutants and Helen Goreham District One debris along the way. Eventually, “stormwater” fl ows into rivers, lakes, or streams, carrying pollutants with it. This impacts the water for both aquati c life and human use. Bob Ott District Two Stormwater polluti on is one of the biggest problems facing the water resources of metropolitan north Georgia. JoAnn Birrell In fact, the majority of the water quality violati ons in the region are due to polluted stormwater runoff . District Three As of 2011, there are over 75 million pet dogs in the United States. Bacteria and other pathogens in pet waste G. Woody Thompson District Four left on yards, sidewalks, streets, and other opened areas can be washed away and carried by rainwater into the storm drains and drainage ditches which fl ow to nearby rivers, lakes, and streams. David Hankerson County Manager • A single gram of pet waste contains an average of 23 million fecal coliform bacteria, some of which can cause disease in humans. Cobb County • Waters that contain high levels of bacteria are unfi t for human contact. Watershed Stewardship • As animal waste decays, it uses up dissolved oxygen that fi sh and aquati c life need. Program 662 South Cobb Drive • Pet waste contains nutrients that can cause excessive algae growth in a river or lake, disturbing the Marietta, Georgia 30060 natural balance. -

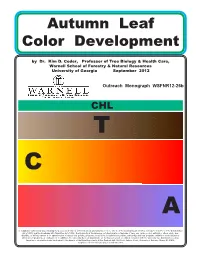

Fall Color Pub 12-26

Autumn Leaf Color Development by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care, Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources University of Georgia September 2012 Outreach Monograph WSFNR12-26b CHL T C red A In compliance with federal law, including the provisions of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Sections 503 and 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the University of Georgia does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, religion, color, national or ethnic origin, age, disability, or military service in its administration of educational policies, programs, or activities; its admissions policies; scholarship and loan programs; athletic or other University- administered programs; or employment. In addition, the University does not discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation consistent with the University non-discrimination policy. Inquiries or complaints should be directed to the director of the Equal Opportunity Office, Peabody Hall, 290 South Jackson Street, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602. Telephone 706-542-7912 (V/TDD). Fax 706-542-2822. Autumn Leaf Color Development by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Trees have many strategies for life. Some grow fast and die young, others grow slow and live a long time. Some trees colonize new soils and new space, while other trees survive and thrive in the midst of old forests. A number of trees invest in leaves which survive several growing seasons, while other trees grow new leaves every growing season. One of the most intriguing and beautiful result of tree life strategies is autumn leaf coloration among deciduous trees. -

What Do Red and Yellow Autumn Leaves Signal?

The Botanical Review 73(4): 279–289 What Do Red and Yellow Autumn Leaves Signal? Simcha Lev-Yadun Department of Biology Faculty of Science and Science Education University of Haifa - Oranim Tivon 36006, Israel and Kevin S. Gould Department of Botany University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand Abstract . 279 Introduction . 280 Previous Hypotheses for the Signaling Function of Red and Yellow Autumn Leaves . 280 Autumn Leaves and the Nature of Signals . 282 We Propose That Autumn Leaves Signal That They Are About to Be Shed . 282 The Risk of Herbivore Attacks and the Strength of Defense . 282 Autumn Leaf Colors Undermine Herbivorous Insect Camouflage . 283 Size of Color Patch and Efficiency of Insect Camouflage . 284 Red and Yellow Autumn Leaves Are Aposematic . 284 Leaf Color Variability . 285 Conclusions . 285 Acknowledgments . 286 Literature Cited . 286 Abstract The widespread phenomenon of red and yellow autumn leaves has recently attracted considerable scientific attention. The fact that this phenomenon is so prominent in the cooler, temperate regions and less common in warmer climates is a good indication of a climate-specific effect. In addition to the putative multifarious physiological benefits, such as protection from photoinhibition and photo-oxidation, several plant/animal inter- action functions for such coloration have been proposed. These include (1) that the bright leaf colors may signal frugivores about ripe fruits (fruit flags) to enhance seed dispersal; (2) that they signal aphids that the trees are well defended (a case of Zahavi’s handicap principle operating in plants); (3) that the coloration undermines herbivore in- sect camouflage; (4) that they function according to the “defense indication hypothesis,” which states that red leaves are chemically defended because anthocyanins correlate with various defensive compounds; or (5) that because sexual reproduction advances the Copies of this issue [73(4)] may be purchased from the NYBG Press, The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY 10458-5125, U.S.A. -

Preferred Tree Species for Northwest Kansas

Preferred Trees for Northwest Kansas Growing trees successfully depends on the selection of the right trees for the intended site. It is important to match the growing conditions and space available on the site with the cultural requirements and projected size of each tree to be planted. The following charts show the tolerance of individual trees to various environmental conditions as well as the major landscape attributes of each tree. Not all trees capable of growing in Northwest Kansas are included. The preferred trees listed are recommended by industry professionals such as city foresters, local tree boards, and horticulture extension agents. For a more extensive list of urban trees see Shade & Ornamental Trees for Kansas MF-2688. KEY TO USING THIS INFORMATION: TREE SPECIES AND CULTIVARS: The names of the trees are listed in the center of four different charts. Three of the charts list deciduous trees according to average mature height, and the fourth chart lists evergreen trees. Cultivars are listed if they possess improved plant characteristics such as attractive fall color, a unique form, attractive flowers or fruit, greater heat tolerance, or increased pest resistance. ENVIRONMENTAL TOLERANCES: The left side of each chart indicates the tolerance of the tree to various environmental conditions including full sun (S), light shade (L), soil pH, and soil moisture tolerances. Each chart also shows the resistance of each tree to insect and disease pests. (Good) under the appropriate column indicates the tree is strongly tolerant of the characteristic indicated. (Fair) signifies that the tree shows some tolerance. A blank space in a column indicates the tree is not tolerant and should not be subjected to that environmental condition. -

Leaves and Photosynthesis

http://na.fs.fed.us/ f you are lucky, you live in one of those parts of the world where Nature has one last fling before settling down into winter's sleep. In those lucky places, as days shorten and temperatures become crisp, the quiet green palette of summer foliage is transformed into the vivid autumn palette of reds, oranges, golds, and browns before the leaves fall off the trees. On special years, the colors are truly breathtaking. How does autumn color happen? For years, scientists have worked to understand the changes that happen to trees and shrubs in the autumn. Although we don't know all the details, we do know enough to explain the basics and help you to enjoy more fully Nature's multicolored autumn farewell. Three factors influence autumn leaf color-leaf pigments, length of night, and weather, but not quite in the way we think. The timing of color change and leaf fall are primarily regulated by the calendar, that is, the increasing length of night. None of the other environmental influences-temperature, rainfall, food supply, and so on-are as unvarying as the steadily increasing length of night during autumn. As days grow shorter, and nights grow longer and cooler, biochemical processes in the leaf begin to paint the landscape with Nature's autumn palette. Where do autumn colors come from? A color palette needs pigments, and there are three types that are involved in autumn color. • Chlorophyll, which gives leaves their basic green color. It is necessary for photosynthesis, the chemical reaction that enables plants to use sunlight to manufacture sugars for their food. -

The Mystery of Seasonal Color Change

The Mystery of Seasonal Color Change David Lee … the gods are growing old; The stars are singing Golden hair to gray Green leaf to yellow leaf,—or chlorophyll To xanthophyll, to be more scientific … Edwin Arlington Robinson (Captain Craig) hroughout New England each autumn— early October in some parts and as much Tas three weeks later in others—the pageant of color change in our forests unfolds. Though less noticed, in the springtime these forest canopies take on delicate pastel colors as buds swell and leaves expand. In the last 15 A red maple leaf shows developing red autumn color along years, our understanding of the science behind with still-green sections. color change has begun to emerge, with two different but not mutually exclusive hypoth- eses being formulated and defended. I have been involved in the research and debate on these color changes, and why that is so is a bit of a mystery in itself. After all, I grew up on the cold desert of the Columbia Plateau in Washington State, where the predominant colors were the grays of sagebrush and other pubescent shrubs. Occasionally I visited the forests of the Cascade Range to the west, witnessing the dark greens of conifers, occasional yellows of cottonwood, birch, and willow in the autumn, with just a few splashes of the reds of the Douglas maple (Acer glabrum var. douglasii). I did enjoy the autumn colors of the mid-Atlantic and Midwest forests as a graduate student and post-doctoral fellow, but was too busy in the laboratory to think much about that color. -

Landscape Controls on the Timing of Spring, Autumn, and Growing Season Length in Mid-Atlantic Forests

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- Published Research US Geological Survey 2012 Landscape controls on the timing of spring, autumn, and growing season length in mid-Atlantic forests Andrew J. Elmore University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, [email protected] Steven M. Guinn University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Burke J. Minsley United States Geological Survey, [email protected] Andrew Richardson Harvard University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Elmore, Andrew J.; Guinn, Steven M.; Minsley, Burke J.; and Richardson, Andrew, "Landscape controls on the timing of spring, autumn, and growing season length in mid-Atlantic forests" (2012). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 514. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/514 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- Published Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Global Change Biology (2012) 18, 656–674, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02521.x Landscape controls on the timing of spring, autumn, and growing season length in mid-Atlantic forests ANDREW J. ELMORE*, STEVEN M. GUINN*, BURKE J. MINSLEY† andANDREW D. RICHARDSON‡ *Appalachian Laboratory, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, 301 Braddock Rd, Frostburg, MD USA, †United States Geological Survey, Crustal Geophysics and Geochemistry Science Center, Denver, CO USA, ‡Department of Organismic & Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA USA Abstract The timing of spring leaf development, trajectories of summer leaf area, and the timing of autumn senescence have profound impacts to the water, carbon, and energy balance of ecosystems, and are likely influenced by global climate change. -

Autumn Colors

■ ,VVXHG LQ IXUWKHUDQFH RI WKH &RRSHUDWLYH ([WHQVLRQ :RUN$FWV RI 0D\ DQG -XQH LQ FRRSHUDWLRQ ZLWK WKH 8QLWHG 6WDWHV 'HSDUWPHQWRI$JULFXOWXUH 'LUHFWRU&RRSHUDWLYH([WHQVLRQ8QLYHUVLW\RI0LVVRXUL&ROXPELD02 NATURAL ■ ■ ■ DQHTXDORSSRUWXQLW\$'$LQVWLWXWLRQ H[WHQVLRQPLVVRXULHGX RESOURCES Autumn Colors he spectacular parade of colors associated with the Indian summer days of autumn is created by a Tcomplicated series of interactions involving pigments, sunlight, moisture, chemicals, hormones, temperature, length of daylight, growing location and genetic traits. A precise clockwork within the leaf cells sets the forests of Missouri ablaze when early fall days are bright and cool, and nights are chilly but not freezing. Several central Missouri highways have reputations for being particularly beautiful autumn drives: • Highway 19 between I-70 and Hermann • Highway 94 north of the Missouri River between Jefferson City and Hermann, • Highway 100 south of the Missouri River between Hermann and Washington. A favorite route for fall foliage watching in eastern Missouri is Highway 79 along the Mississippi River between Winfield and Hannibal. Good colors can also be found on the bluffs along the Figure 1. The white limestone bluffs along the Katy Trail in central Missouri Missouri River Trail in the central part of the state around provide a striking contrast to the autumn colors of surrounding forests. Columbia and the Piedmont area around Ironton (Figure 1). the base of the leaf stem. These abscission zones eventually The leaves of the growing season are green because break apart from wind or other physical disturbances, of the formation of chlorophyll, a pigment found in often causing the leaf to fall before the yellow and red minute leaf structures called plastids. -

Early Autumn Senescence in Red Maple (Acer Rubrum L.) Is Associated with High Leaf Anthocyanin Content

Plants 2015, 4, 505-522; doi:10.3390/plants4030505 OPEN ACCESS plants ISSN 2223-7747 www.mdpi.com/journal/plants Article Early Autumn Senescence in Red Maple (Acer rubrum L.) Is Associated with High Leaf Anthocyanin Content Rachel Anderson and Peter Ryser * Department of Biology, Laurentian University, 935 Ramsey Lake Road, Sudbury, ON P3E 2H6, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-705-675-1151 (ext. 2353); Fax: +1-705-675-4859. Academic Editor: Salma Balazadeh Received: 24 June 2015 / Accepted: 30 July 2015 / Published: 5 August 2015 Abstract: Several theories exist about the role of anthocyanins in senescing leaves. To elucidate factors contributing to variation in autumn leaf anthocyanin contents among individual trees, we analysed anthocyanins and other leaf traits in 27 individuals of red maple (Acer rubrum L.) over two growing seasons in the context of timing of leaf senescence. Red maple usually turns bright red in the autumn, but there is considerable variation among the trees. Leaf autumn anthocyanin contents were consistent between the two years of investigation. Autumn anthocyanin content strongly correlated with degree of chlorophyll degradation mid to late September, early senescing leaves having the highest concentrations of anthocyanins. It also correlated positively with leaf summer chlorophyll content and dry matter content, and negatively with specific leaf area. Time of leaf senescence and anthocyanin contents correlated with soil pH and with canopy openness. We conclude that the importance of anthocyanins in protection of leaf processes during senescence depends on the time of senescence.