2018 Inquiry Into Options for the Reform of Political Funding and Donations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ready Programs and the Papulu CLC Director David Ross

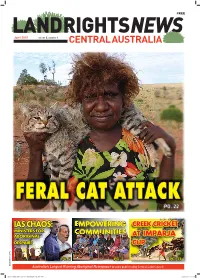

FREE April 2015 VOLUME 5. NUMBER 1. PG. ## FERAL CAT ATTACK PG. 22 IAS CHAOS: EMPOWERING CREEK CRICKET MINISTERS FOR COMMUNITIES ABORIGINAL AT IMPARJA DESPAIR? CUP PG. 2 PG. 2 PG. 33 ISSN 1839-5279 59610 CentralLandCouncil CLC Newspaper 36pp Alts1.indd 1 10/04/2015 12:32 pm NEWS Aboriginal Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion confronts an EDITORIAL angry crowd at the Alice Springs Convention Centre. Land Rights News Central He said organisations got the funding they deserved. Australia is published by the Central Land Council three times a year. The Central Land Council 27 Stuart Hwy Alice Springs NT 0870 tel: 89516211 www.clc.org.au email [email protected] Contributions are welcome SUBSCRIPTIONS Land Rights News Central Australia subscriptions are $20 per year. LRNCA is distributed free to Aboriginal organisations and communities in Central Australia Photo courtesy CAAMA To subscribe email: [email protected] IAS chaos sparks ADVERTISING Advertise in the only protests and probe newspaper to reach Aboriginal people THE AUSTRALIAN Senate will inquire original workers. Neighbouring Barkly Regional Council re- into the delayed and chaotic funding round Nearly half of the 33 organisations sur- ported 26 Aboriginal job losses as a result of in remote Central of the new Indigenous advancement scheme veyed by the Alice Springs Chamber of Com- a 35% funding cut to community services in a (IAS), which has done as much for the PM’s merce were offered less funding than they had UHJLRQWURXEOHGE\SHWUROVQLI¿QJ Australia. reputation in Aboriginal Australia as his way previously for ongoing projects. President Barb Shaw told the Tennant with words. -

Public Forum 11 November 2015

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 12th Assembly Public Accounts Committee Inquiry into Funding of Rugby League Facilities in Darwin Public Forum Transcript 5.00 pm, Wednesday, 11 November 2015 Litchfield Room, Parliament House Members: Mrs Robyn Lambley, MLA, Chair, Member for Araluen Ms Natasha Fyles, MLA, Member for Nightcliff Ms Nicole Manison, MLA, Member for Wanguri Mr Gerry Wood, MLA, Member for Nelson Witnesses: Brad and Cherill Hopkins Michael Hawkes Inge van Sprang Jude Scott Ron Grolep Margaret Clinch Jennie Renfree Rollo Manning Robyn MacGillivray Ian McNeill Karen O’Dwyer Public Accounts Committee – Inquiry into Funding of Rugby League Facilities in Darwin Madam CHAIR: I welcome everyone here this evening to the inquiry into Richardson Park by the Public Accounts Committee. It is great of you to come along at such short notice; I think most of you were only advised of this yesterday. We decided it was important for local residents affected by the upgrade to Richardson Park to have an opportunity to talk to us. We will have a fairly informal approach to this afternoon; we want to listen to what you have to say. We can give a little feedback from what we have heard and have been able to glean from the documentation provided to the committee today. I ask that you be mindful of the fact this is a formal proceedings as a public hearing; it is being webcast through the Assembly’s website. A transcript will be made for use of the committee and may be put on the committee’s website. That is not to deter you from being frank and open, if that is what you want to be. -

Vocational Education & Training

VOCATIONAL EDUCATION & TRAINING The Northern Territory’s history of public philanthropy VOCATIONAL EDUCATION & TRAINING The Northern Territory’s history of public philanthropy DON ZOELLNER Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Zoellner, Don, author. Title: Vocational education and training : the Northern Territory’s history of public philanthropy / Don Zoellner. ISBN: 9781760460990 (paperback) 9781760461003 (ebook) Subjects: Vocational education--Government policy--Northern Territory. Vocational education--Northern Territory--History. Occupational training--Government policy--Northern Territory. Occupational training--Northern Territory--History. Aboriginal Australians--Vocational education--Northern Territory. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: ‘Northern Territory Parliament House main entrance’ by Patrick Nelson. This edition © 2017 ANU Press Contents List of figures . vii Foreword . xi Acknowledgements . xiii 1 . Setting the scene . 1 2 . Philanthropic behaviour . 11 3 . Prior to 1911: European discovery and South Australian administration of the Northern Territory . 35 4 . Early Commonwealth control, 1911–46 . 45 5 . The post–World War Two period to 1978 . 57 6. TAFE in the era of self‑government, 1978–92 . 99 7. Vocational education and training in the era of self‑government, 1992–2014 . 161 8. Late 2015 and September 2016 postscript . 229 References . 243 List of figures Figure 1. -

2008 NORTHERN TERRITORY ELECTION 9 August 2008

2008 NORTHERN TERRITORY ELECTION 9 August 2008 CONTENTS Page Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 Legislative Assembly Results Summary of Legislative Assembly Election ............................................................... 3 Legislative Assembly Results by Electoral Division.................................................... 6 By-elections 2005-2008 ........................................................................................... 10 Summary of Two-Party Preferred Results ............................................................... 11 Regional Summaries ............................................................................................... 14 Members Elected .................................................................................................... 16 Symbols .. Nil or rounded to zero * Sitting MPs .… „Ghost‟ candidate, where a party contesting the previous election did not nominate for the current election Party Abbreviations (blank) Non-affiliated candidates CLP Country Liberal Party GRN Green IND Independent LAB Territory Labor OTH Others Relevant dates Issue of Writ Tuesday 22 July 2008 Close of Electoral Roll 8pm Thursday 24 July 2008 Close of Nominations 12 noon Monday 28 July 2008 Commencement of Mobile and Postal voting Thursday 31 July 2008 Polling Day Saturday 9 August 2008 Close of Receipt for Postal Votes 6pm Friday 15 August 2008 Declaration of Polls 10am Monday 18 August 2008 Return -

An Investigation Into the Phraseology of Question

ORDER! ORDER!: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE PHRASEOLOGY OF QUESTION TIME IN THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND HOUSES OF REPRESENTATIVES A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the University of Canterbury by Irina Loginova University of Canterbury 2013 Table of contents: Acknowledgements viii Abstract xi List of abbreviations and acronyms xiii List of figures, tables, graphs and diagrams xiv Figures xiv Tables xv Graphs xix Diagrams xxi Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1. Aims 1 1.1. Why examine Question Time? 1 1.2. Exploration of genrelects in general and methodology for their study 3 2. Analytic framework 5 2.1. Pre-elections 7 2.2. Reasons for the study 8 3. Methods 8 4. Outcomes 11 Chapter 2: PHRASEOLOGY OF QUESTION TIME 13 i 1. Introduction 13 2. Speech genres 13 3. Speech community, community of practice, discourse community 14 4. Summary of Chapter 2 23 Chapter 3: METHODOLOGY 25 1. Introduction 25 2. Developing a database for the study of the phraseology and ethnography of Parliamentary Question Time 26 3. The use of linguistic corpus tools for PLIs selection 40 4. Summary of Chapter 3 48 Chapter 4: HISTORIC OVERVIEW OF PARLIAMENTARY TRADITIONS IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA 50 1. Introduction 50 2. Question Time as a communicative performance 50 3. History and geography of Australia and New Zealand 55 4. Summary of Chapter 4 63 Chapter 5: ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF QUESTION TIME 65 1. Introduction 65 2. Question Time as a ritual 65 2.1. Question Time in the New Zealand Parliament 66 ii 2.1.1. -

2012 NORTHERN TERRITORY ELECTION 25 August 2012

2012 NORTHERN TERRITORY ELECTION 25 August 2012 CONTENTS Page Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 Legislative Assembly Results Summary of Legislative Assembly Election ............................................................... 3 Legislative Assembly Results by Electoral Division.................................................... 6 By-elections 2008-2012 ........................................................................................... 10 Summary of Two-Party Preferred Results ............................................................... 11 Regional Summaries ............................................................................................... 14 Symbols .. Nil or rounded to zero * Sitting MPs .… ‘Ghost’ candidate, where a party contesting the previous election did not nominate for the current election (n.a.) Not available Party Abbreviations - Non-affiliated candidates ASXP Australian Sex Party CLP Country Liberal Party FNP First Nation's Party GRN Green IND Independent LAB Territory Labor OTH Others Relevant dates Issue of Writ Monday 6 August 2012 Close of Electoral Roll 8pm Wednesday 8 August 2012 Close of Nominations 12 noon Friday 10 August 2012 Polling Day Saturday 25 August 2012 Declaration of Poll and Return of Writ Monday 3 September 2012 Late Date for Return of Writ Friday 28 September 2012 2 Antony Green – ABC Election Unit – July 2016 2012 Northern Territory Election INTRODUCTION This paper contains -

Public Hearing 12 November 2015

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 12th Assembly Public Accounts Committee Inquiry into Funding of Rugby League Facilities in Darwin Public Hearing Transcript 8.30 am, Thursday, 12 November 2015 Litchfield Room, Parliament House Members: Mrs Robyn Lambley, MLA, Chair, Member for Araluen Ms Natasha Fyles, MLA, Member for Nightcliff Ms Nicole Manison, MLA, Member for Wanguri Mr Gerry Wood, MLA, Member for Nelson Witnesses: Minister for Sport and Recreation The Honourable Gary Higgins, MLA, Minister for Sport and Recreation Mr Ian Ford, MLA, Acting Chief Executive Department of Education Mr Ken Davies, Chief Executive Department of the Chief Minister Mr John Coleman, Chief Executive National Rugby League (NRL) and NRL Northern Territory Mr Jaymes Boland-Rudder, Head of Government Relations and Campaign Management, NRL Mr John Mitchell, General Manager, NRL Northern Territory Mr Nigel Roy, Operations Manager, NRL Northern Territory Department of Lands, Planning and the Environment Mr Rod Applegate, Chief Executive Public Accounts Committee – Inquiry into Funding of Rugby League Facilities in Darwin The committee convened at 8.30 am. MINISTER FOR SPORT AND RECREATION Madam CHAIR: I welcome to the table to give evidence this morning the Minister for Sport and Recreation, Hon Gary Higgins MLA, and Mr Ian Ford, Acting Chief Executive of the Department of Sport and Recreation. Thank you for coming in this morning. We appreciate you taking the time to speak to the committee and look forward to hearing from you today. This is a formal proceeding of the committee and the protection of parliamentary privilege and the obligation not to mislead the committee apply. -

House of Representatives Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES House of Representatives Official Hansard No. 2, 2010 Monday, 18 October 2010 FORTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—FIRST PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES INTERNET The Votes and Proceedings for the House of Representatives are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/house/info/votes Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard For searching purposes use http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au SITTING DAYS—2010 Month Date February 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 22, 23, 24, 25 March 9, 10, 11, 15, 16, 17, 18 May 11, 12, 13, 24, 25, 26, 27, 31 June 1, 2, 3, 15, 16, 17, 21, 22, 23, 24 September 28, 29, 30 October 18, 19, 20, 21, 25, 26, 27, 28 November 15, 16, 17, 18, 22, 23, 24, 25 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on ABC NewsRadio in the capital cities on: ADELAIDE 972AM BRISBANE 936AM CANBERRA 103.9FM DARWIN 102.5FM HOBART 747AM MELBOURNE 1026AM PERTH 585AM SYDNEY 630AM For information regarding frequencies in other locations please visit http://www.abc.net.au/newsradio/listen/frequencies.htm FORTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—FIRST PERIOD Governor-General Her Excellency Ms Quentin Bryce, Companion of the Order of Australia House of Representatives Officeholders Speaker—Mr Harry Alfred Jenkins MP Deputy Speaker— Hon. Peter Neil Slipper MP Second Deputy Speaker—Hon. Bruce Craig Scott MP Members of the Speaker’s Panel—Ms Anna Elizabeth Burke MP, Hon. -

The Numbers Game

SUNDAY SEPTEMBER 11 2016 FRONTIER 17 ASK WOODY Advice from DAVID WOOD to help you muddle your way through the confusing territory that comes with the Territory Dear Woody, I work for an institution that really polarises people. Some love us, some hate us. Unfortunately, the ones who hate us seem to be the more vocal and physical, and like to pop in and pay us a visit now and then. Sometimes they even leave a calling card, such as a rock through a window. Or a rock through a window of our cruddy four wheel-drive. There’s nothing great about a Great Wall with a broken window. It’s just a Wall. Anyway, I fear for my safety at work on a daily basis. What advice do you have? Dear Matt Williams, What utter, utter bastards. Yeah, that is really terrible. Why would anyone want to throw a rock through the window of such an august publication? One of the newspapers of record, alongside The New York Times, The Guardian, The Wall Street Journal, The Times of London, Shepparton News, the Latrobe Valley Express, the East Timor Guide Post. Why would anyone do such a thing? You can’t have many people who hold a grudge, except perhaps Adam Giles, John Elferink, Lia Finocchiaro, Gary Higgins, the Butcher of Barunga, Alison Anderson, Willem “Brief Minister” Westra van Holthe, Peter Chandler, Dave Tollner, Bess Price, Nathan Barrett, Peter Styles, Matt Conlon, “I’m 45 and I remember being evacuated when Cyclone Tracy blew through town. It was a crazy time. -

Ranger 3 Deeps Underground Mine Overview of Communication and Consultation

Energy Resources of Australia Ltd Ranger 3 Deeps underground mine Overview of Communication and Consultation Date: 14 January 2013 1. Overview Energy Resources of Australia Ltd (ERA) is a 68.4 % owned subsidiary of the Rio Tinto group. ERA owns and operates the Ranger uranium mine. ERA is one of the nation’s largest uranium producers and Australia’s longest continually operating uranium mine. Uranium has been mined at Ranger for three decades. Ranger mine is one of only three mines in the world to have produced in excess of 100,000 tonnes of uranium oxide (U3O8). ERA’s Ranger mine is located approximately 11km east of Jabiru and 260 km east of Darwin, in Australia’s Northern Territory (NT). The mine lies within the 79 km 2 Ranger Project Area and is adjacent to Magela Creek, a tributary of the East Alligator River. Ranger uranium mine is an open cut mine which commenced commercial production of drummed U3O8 in 1981. ERA sells its product to power utilities in Asia, Europe and North America under strict international and Australian Government safeguards. It maintains long-term relationships with customers by providing consistent and reliable supply of uranium oxide in order to meet their energy needs. The resource, referred to as Ranger 3 Deeps, has been defined by a series of successive surface diamond drilling programs from 2005–2009. Additional diamond drilling will occur via the Ranger 3 Deeps exploration decline, which was approved for construction on 25 August 2011. The proposed action is to mine and process the uranium bearing ore from the Ranger 3 Deeps mineral resource, which is estimated to contain approximately 34,000 tonnes of U 3O8. -

Contents Visitors

DEBATES – Thursday 23 March 2017 CONTENTS VISITORS ................................................................................................................................................. 1347 Moulden Primary School ....................................................................................................................... 1347 Speaker’s statement ................................................................................................................................. 1347 Terror Attacks in London ....................................................................................................................... 1347 LEAVE OF ABSENCE .............................................................................................................................. 1347 Deputy Chief Minister ............................................................................................................................ 1347 MINISTERIAL ARRANGEMENTS ............................................................................................................ 1348 Question Time ....................................................................................................................................... 1348 MINISTERIAL STATEMENT ..................................................................................................................... 1348 Supporting Territory Women ................................................................................................................. 1348 VISITORS ................................................................................................................................................ -

Parl Matters Issue 25

Issue No 25 - February 2011 2011-12 ANZACTT Executive Parliament Matters President PARLIAMENT MATTERS is a half-yearly bulle- Robyn McClelland House of Representatives tin published for the Australia and New Zea- land Association of Clerks-at-the-Table. Vice President One of the purposes of Parliament Matters Peter McHugh Western Australia Legislative Assembly is to inform our members and other staff of parliaments in Australia and New Zealand Secretary-Treasurer of new and continuing procedural and ad- Rick Crump South Australia House of Assembly ministrative developments that may have some practical application in their jurisdic- Executive Member tion. David Wilson New Zealand House of Representatives It also acts as a forum for the sharing of pro- fessional experiences, consultation and col- Chair, Education Committee laboration among our members and other David Blunt New South Wales Legislative Council parliamentary staff. Please e-mail contributions to: Chair, Professional Development Committee [email protected]. Telephone 08-8946 Andrew Young 1501, mobile 0419 803891. Victoria Legislative Council Chair, Case Law Committee Debra Angus New Zealand House of Representatives Returning Officer Russell Grove New South Wales Legislative Assembly Parliament Matters Editor Robyn Smith Northern Territory Legislative Assembly Parliament Matters • Issue 25, February 2011 • Page 1 In Issue 25 - February 2011 AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY - LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 5 ○○○○○○○○○○○○ Bill reconsidered at conclusion of detail stage ○○○○○○○○○○○○ 5 Version