Political Chronicles Commonwealth of Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Purpose Standing Committee No. 1 Premier

<1> GENERAL PURPOSE STANDING COMMITTEE NO. 1 Monday 13 September 2004 Examination of proposed expenditure for the portfolio area PREMIER, ARTS AND CITIZENSHIP The Committee met at 5.30 p.m. MEMBERS The Hon. P. T. Primrose (Chair) The Hon. A. R. Fazio Ms L. Rhiannon The Hon. M. J. Pavey The Hon. E. M. Roozendaal The Hon. G. S. Pearce _______________ PRESENT The Hon. R. J. Carr, Premier, Minister for the Arts, and Minister for Citizenship Premier's Department Dr C. Gellatly, Director-General Cabinet Office Mr R. Wilkins, Director General _______________ CORRECTIONS TO TRANSCRIPT OF COMMITTEE PROCEEDINGS Corrections should be marked on a photocopy of the proof and forwarded to: Budget Estimates secretariat Room 812 Parliament House Macquarie Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 CHAIR: In relation to the conduct of the hearing, while the budget estimates resolution does not prescribe procedures for the following matters, the Committee has previously determined that, unless the Committee resolves otherwise: first, witnesses are to be requested to provide answers to oral questions taken on notice during the hearing within 35 calendar days; and, second, the sequence of questioning is to be left in the hands of the Chair. I propose to allow the sequence of questions as 20 minutes each, and then we will go round the room, Opposition, crossbench and then Government. I refer to the broadcasting of proceedings. Before the questioning of witnesses commences, I remind Committee members that the Committee has previously authorised the broadcasting of all its public proceedings. Should it be considered that the broadcasting of these proceedings be discontinued, a member will be required to move a motion accordingly. -

Legislative Assembly

11282 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Wednesday 22 September 2004 ______ Mr Speaker (The Hon. John Joseph Aquilina) took the chair at 11.00 a.m. Mr Speaker offered the Prayer. MINISTRY Mr BOB CARR: In the absence of the Minister for Tourism and Sport and Recreation, and Minister for Women, who is undergoing an operation, the Deputy Premier, Minister for Education and Training, and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs will answer questions on her behalf. In the absence of the Minister for Mineral Resources, the Minister for Fair Trading, and Minister Assisting the Minister for Commerce will answer questions on his behalf. In the absence of the Minister for Infrastructure and Planning, and Minister for Natural Resources, the Attorney General, and Minister for the Environment will answer questions on his behalf. DISTINGUISHED VISITORS Mr SPEAKER: I welcome to the Public Gallery Mrs Sumitra Singh, the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of the State of Rajasthan in India, who is accompanied by her son, and Mrs Harsukh Ram Poonia, Secretary of the Rajasthan Legislative Assembly. PETITIONS Milton-Ulladulla Public School Infrastructure Petition requesting community consultation in the planning, funding and building of appropriate public school infrastructure in the Milton-Ulladulla area and surrounding districts, received from Mrs Shelley Hancock. Gaming Machine Tax Petitions opposing the increase in poker machine tax, received from Mrs Shelley Hancock, Mrs Judy Hopwood and Mr Andrew Tink. Crime Sentencing Petition requesting changes in legislation to allow for tougher sentences for crime, received from Mrs Shelley Hancock. Lake Woollumboola Recreational Use Petition opposing any restriction of the recreational use of Lake Woollumboola, received from Mrs Shelley Hancock. -

Scott Brenton's Monograph

Parliamentary Library Parliamentary Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Dr Scott Brenton What lies beneath: the work of senators and members in WHAT LIES BENEATH THE WORK OF SENATORS AND MEMBERS IN THE AUSTRALIAN PARLIAMENT Dr Scott Brenton 2009 Australian Parliamentary Fellow the Australian Parliament What lies beneath: the work of senators and members in the Australian Parliament Dr Scott Brenton 2009 Australian Parliamentary Fellow ISBN 978-0-9806554-1-4 © Commonwealth of Australia 2010 This work is copyright. Except to the extent of uses permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, no person may reproduce or transmit any part of this work by any process without the prior written consent of the Parliamentary Librarian. This requirement does not apply to members of the Parliament of Australia acting in the course of their official duties. This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion. Feedback is welcome and may be provided to: [email protected]. Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with senators and members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library’s Central Entry Point for referral. Disclaimer This work has been edited according to the Parliamentary Library style guide, and does not necessarily represent the author’s original style. -

Letter from Melbourne Is a Monthly Public Affairs Bulletin, a Simple Précis, Distilling and Interpreting Mother Nature

SavingLETTER you time. A monthly newsletter distilling FROM public policy and government decisionsMELBOURNE which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. Saving you time. A monthly newsletter distilling public policy and government decisions which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. p11-14: Special Melbourne Opera insert Issue 161 Our New Year Edition 16 December 2010 to 13 January 2011 INSIDE Auditing the state’s affairs Auditor (VAGO) also busy Child care and mental health focus Human rights changes Labor leader no socialist. Myki musings. Decision imminent. Comrie leads Victorian floods Federal health challenge/changes And other big (regional) rail inquiry HealthSmart also in the news challenge Baillieu team appointments New water minister busy Windsor still in the news 16 DECEMBER 2010 to 13 JANUARY 2011 14 Collins Street EDITORIAL Melbourne, 3000 Victoria, Australia Our government warming up. P 03 9654 1300 Even some supporters of the Baillieu government have commented that it is getting off to a slow F 03 9654 1165 start. The fact is that all ministers need a chief of staff and specialist and other advisers in order to [email protected] properly interface with the civil service, as they apply their new policies and different administration www.letterfromcanberra.com.au emphases. These folk have to come from somewhere and the better they are, the longer it can take for them to leave their current employment wherever that might be and settle down into a government office in Melbourne. Editor Alistair Urquhart Some stakeholders in various industries are becoming frustrated, finding it difficult to get the Associate Editor Gabriel Phipps Subscription Manager Camilla Orr-Thomson interaction they need with a relevant minister. -

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development Annual Report 2010–11 Published by the Communications Division for Strategy and Coordination Division Department of Education and Early Childhood Development Melbourne September 2011 © State of Victoria (Department of Education and Early Childhood Development) 2011 The copyright in this document is owned by the State of Victoria (Department of Education and Early Childhood Development), or in the case of some materials, by third parties (third party materials). No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, the National Education Access Licence for Schools (NEALS) (see below) or with permission. An educational institution situated in Australia which is not conducted for profit, or a body responsible for administering such an institution, may copy and communicate the materials, other than third party materials, for the educational purposes of the institution. Authorised by the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, 2 Treasury Place, East Melbourne, Victoria, 3002. ISBN No. 978-0-7594-0627-8 Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an accessible format, such as large print or audio, please telephone 1800 809 834 or email [email protected] This document is also available in PDF format on the internet at www.education.vic.gov.au This report is printed on Tudor RP 100% Recycled which is Australian made, carbon neutral and made entirely from recycled waste paper. This sustainable paper is made under world’s best practice ISO 14001 Environmental Management System. September 2011 The Hon. Peter Hall MLC The Minister for Higher Education and Skills Minister responsible for the Teaching Profession The Hon. -

Political Overview

ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL OVERVIEW PHOTO: PAUL LOVELACE PHOTOGRAPHY Professor Ken Wiltshire AO Professor Ken Wiltshire is the JD Story Professor of Public Administration at the University of Queensland Business School. He is a Political long-time contributor to CEDA’s research and an honorary trustee. overview As Australia enters an election year in 2007, Ken Wiltshire examines the prospects for a long-established Coalition and an Opposition that has again rolled the leadership dice. 18 australian chief executive RETROSPECT 2006 Prime Minister and Costello as Treasurer. Opinion Politically, 2006 was a very curious and topsy-turvy polls and backbencher sentiment at the time vindi- … [Howard] became year. There was a phase where the driving forces cated his judgement. more pragmatic appeared to be the price of bananas and the depre- From this moment the Australian political than usual … dations of the orange-bellied parrot, and for a dynamic changed perceptibly. Howard had effec- nation that has never experienced a civil war there tively started the election campaign, and in the “ were plenty of domestic skirmishes, including same breath had put himself on notice that he culture, literacy, and history wars. By the end of the would have to win the election. Almost immedi- year both the government and the Opposition had ately he became even more pragmatic than usual, ” changed their policy stances on a wide range of and more flexible in policy considerations, espe- issues. cially in relation to issues that could divide his own Coalition. The defining moment For Kim Beazley and the ALP, Howard’s decision The defining moment in Australian politics was clearly not what they had wanted, despite their occurred on 31 July 2006 when Prime Minister claims to the contrary, but at least they now knew John Howard, in response to yet another effort to the lay of the battleground and could design appro- revive a transition of leadership to his Deputy Peter priate tactics. -

Report X Terminology Xi Acknowledgments Xii

Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee Consideration of Legislation Referred to the Committee Euthanasia Laws Bill 1996 March 1997 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee Consideration of Legislation Referred to the Committee Euthanasia Laws Bill 1996 March 1997 © Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISSN 1326-9364 This document was produced from camera-ready copy prepared by the Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee, and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. Members of the Legislation Committee Members Senator E Abetz, Tasmania, Chair (Chair from 3 March 1997) Senator J McKiernan, Western Australia, Deputy Chair Senator the Hon N Bolkus, South Australia Senator H Coonan, New South Wales (from 26 February 1997: previously a Participating Member) Senator V Bourne, New South Wales (to 3 March 1997) Senator A Murray, Western Australia (from 3 March 1997) Senator W O’Chee, Queensland Participating Members All members of the Opposition: and Senator B Brown, Tasmania Senator M Colston, Queensland Senator the Hon C Ellison, Western Australia (from 26 February 1997: previously the Chair) Senator J Ferris, South Australia Senator B Harradine, Tasmania Senator W Heffernan, New South Wales Senator D Margetts, Western Australia Senator J McGauran, Victoria Senator the Hon N Minchin, South Australia Senator the Hon G Tambling, Northern Territory Senator J Woodley, Queensland Secretariat Mr Neil Bessell (Secretary -

CONTENTS Trust in Government

QUESTIONS – Tuesday 15 August 2017 CONTENTS Trust in Government ................................................................................................................................ 367 Jobs – Investment in the Northern Territory ............................................................................................ 367 NT News Article ....................................................................................................................................... 368 Same-Sex Marriage Plebiscite ................................................................................................................ 369 Police Outside Bottle Shops .................................................................................................................... 369 SUPPLEMENTARY QUESTION ................................................................................................................. 370 Police Outside Bottle Shops .................................................................................................................... 370 Moody’s Credit Outlook ........................................................................................................................... 370 Indigenous Employment .......................................................................................................................... 371 Alcohol-Related Harm Costs ................................................................................................................... 372 Correctional Industries ............................................................................................................................ -

Political Finance in Australia

Political finance in Australia: A skewed and secret system Prepared by Sally Young and Joo-Cheong Tham for the Democratic Audit of Australia School of Social Sciences The Australian National University Report No.7 Table of contents An immigrant society PAGE ii The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be The Democratic Audit of Australia vii PAGE iii taken to represent the views of either the Democratic Audit of Australia or The Tables iv Australian National University Figures v Abbreviations v © The Australian National University 2006 Executive Summary ix National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data 1 Money, politics and the law: Young, Sally. Questions for Australian democracy Political Joo-Cheong Tham 1 Bibliography 2 Private funding of political parties Political finance in Australia: a skewed and secret system. Joo-Cheong Tham 8 ISBN 0 9775571 0 3 (pbk). 3 Public funding of political parties Sally Young 36 ISBN 0 9775571 1 1 (online). 4 Government and the advantages of office 1. Campaign funds - Australia. I. Tham, Joo-Cheong. II. Sally Young 61 Australian National University. Democratic Audit of 5 Party expenditure Australia. III. Title. (Series: Democratic Audit of Sally Young 90 Australia focussed audit; 7). 6 Questions for reform Joo-Cheong Tham and Sally Young 112 324.780994 7 Conclusion: A skewed and secret system 140 An online version of this paper can be found by going to the Democratic Audit of Australia website at: http://democratic.audit.anu.edu.au References and further -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CHRETIEN LEGACY Introduction .................................................. i The Chr6tien Legacy R eg W hitaker ........................................... 1 Jean Chr6tien's Quebec Legacy: Coasting Then Stickhandling Hard Robert Y oung .......................................... 31 The Urban Legacy of Jean Chr6tien Caroline Andrew ....................................... 53 Chr6tien and North America: Between Integration and Autonomy Christina Gabriel and Laura Macdonald ..................... 71 Jean Chr6tien's Continental Legacy: From Commitment to Confusion Stephen Clarkson and Erick Lachapelle ..................... 93 A Passive Internationalist: Jean Chr6tien and Canadian Foreign Policy Tom K eating ......................................... 115 Prime Minister Jean Chr6tien's Immigration Legacy: Continuity and Transformation Yasmeen Abu-Laban ................................... 133 Renewing the Relationship With Aboriginal Peoples? M ichael M urphy ....................................... 151 The Chr~tien Legacy and Women: Changing Policy Priorities With Little Cause for Celebration Alexandra Dobrowolsky ................................ 171 Le Petit Vision, Les Grands Decisions: Chr~tien's Paradoxical Record in Social Policy M ichael J. Prince ...................................... 199 The Chr~tien Non-Legacy: The Federal Role in Health Care Ten Years On ... 1993-2003 Gerard W . Boychuk .................................... 221 The Chr~tien Ethics Legacy Ian G reene .......................................... -

Publications for David Clune 2020 2019 2018

Publications for David Clune 2020 Clune, D., Smith, R. (2019). Back to the 1950s: the 2019 NSW Clune, D. (2020), 'Warm, Dry and Green': release of the 1989 Election. Australasian Parliamentary Review, 34(1), 86-101. <a Cabinet papers, NSW State Archives and Records Office, 2020. href="http://dx.doi.org/10.3316/informit.950846227656871">[ More Information]</a> Clune, D. (2020). A long history of political corruption in NSW: and the downfall of MPs, ministers and premiers. The Clune, D. (2019). Big-spending blues. Inside Story. <a Conversation. <a href="https://theconversation.com/the-long- href="https://insidestory.org.au/big-spending-blues/">[More history-of-political-corruption-in-nsw-and-the-downfall-of-mps- Information]</a> ministers-and-premiers-147994">[More Information]</a> Clune, D. (2019). Book Review. The Hilton bombing: Evan Clune, D. (2020). Book review: 'Dead Man Walking: The Pederick and the Ananda Marga. Australasian Parliamentary Murky World of Michael McGurk and Ron Medich, by Kate Review, 34(1). McClymont with Vanda Carson. Melbourne: Vintage Australia, Clune, D. (2019). Book Review: "Run for your Life" by Bob 2019. Australasian Parliamentary Review, 34(2), 147-148. <a Carr. Australian Journal of Politics and History, 65(1), 146- href="https://www.aspg.org.au/wp- 147. <a href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ajph.12549">[More content/uploads/2020/06/Book-Review-Dead-Man- Information]</a> Walking.pdf">[More Information]</a> Clune, D. (2019). Close enough could be good enough. Inside Clune, D. (2020). Book review: 'The Fatal Lure of Politics: The Story. <a href="https://insidestory.org.au/close-enough-could- Life and Thought of Vere Gordon Childe', by Terry Irving. -

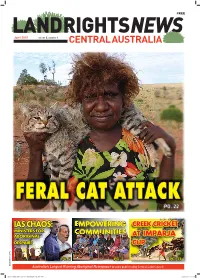

Ready Programs and the Papulu CLC Director David Ross

FREE April 2015 VOLUME 5. NUMBER 1. PG. ## FERAL CAT ATTACK PG. 22 IAS CHAOS: EMPOWERING CREEK CRICKET MINISTERS FOR COMMUNITIES ABORIGINAL AT IMPARJA DESPAIR? CUP PG. 2 PG. 2 PG. 33 ISSN 1839-5279 59610 CentralLandCouncil CLC Newspaper 36pp Alts1.indd 1 10/04/2015 12:32 pm NEWS Aboriginal Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion confronts an EDITORIAL angry crowd at the Alice Springs Convention Centre. Land Rights News Central He said organisations got the funding they deserved. Australia is published by the Central Land Council three times a year. The Central Land Council 27 Stuart Hwy Alice Springs NT 0870 tel: 89516211 www.clc.org.au email [email protected] Contributions are welcome SUBSCRIPTIONS Land Rights News Central Australia subscriptions are $20 per year. LRNCA is distributed free to Aboriginal organisations and communities in Central Australia Photo courtesy CAAMA To subscribe email: [email protected] IAS chaos sparks ADVERTISING Advertise in the only protests and probe newspaper to reach Aboriginal people THE AUSTRALIAN Senate will inquire original workers. Neighbouring Barkly Regional Council re- into the delayed and chaotic funding round Nearly half of the 33 organisations sur- ported 26 Aboriginal job losses as a result of in remote Central of the new Indigenous advancement scheme veyed by the Alice Springs Chamber of Com- a 35% funding cut to community services in a (IAS), which has done as much for the PM’s merce were offered less funding than they had UHJLRQWURXEOHGE\SHWUROVQLI¿QJ Australia. reputation in Aboriginal Australia as his way previously for ongoing projects. President Barb Shaw told the Tennant with words.