Report by 15 March 2007, on the Recommendation of the Selection of Bills Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rudd Government Australian Commonwealth Administration 2007–2010

The Rudd Government Australian Commonwealth Administration 2007–2010 The Rudd Government Australian Commonwealth Administration 2007–2010 Edited by Chris Aulich and Mark Evans Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/rudd_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: The Rudd government : Australian Commonwealth administration 2007 - 2010 / edited by Chris Aulich and Mark Evans. ISBN: 9781921862069 (pbk.) 9781921862076 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Rudd, Kevin, 1957---Political and social views. Australian Labor Party. Public administration--Australia. Australia--Politics and government--2001- Other Authors/Contributors: Aulich, Chris, 1947- Evans, Mark Dr. Dewey Number: 324.29407 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by ANU E Press Illustrations by David Pope, The Canberra Times Printed by Griffin Press Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Contributors . ix Part I. Introduction 1 . It was the best of times; it was the worst of times . 3 Chris Aulich 2 . Issues and agendas for the term . 17 John Wanna Part II. The Institutions of Government 3 . The Australian Public Service: new agendas and reform . 35 John Halligan 4 . Continuity and change in the outer public sector . -

Drivers Impelling Agencies to Digitise

The Evidence in Plain Sight: Drivers Impelling Agencies to Digitise NOVEMBER 2020 Foreword I’d like to thank Intermedium for the opportunity to sponsor this paper capturing the digital imperative for the public sector, which has been made acute by the unprecedented speed, scale and flexibility challenges of COVID-19. The drivers identified in this paper echo the feedback we are hearing from the experiences of our government customers. Salesforce is delighted to partner with both Intermedium and Government as we work towards further empowering the Australian public service to address the policy and service delivery challenges of the ‘new normal’. Barry Dietrich General Manager & Senior Vice President, Public Sector APAC, Salesforce The Evidence in Plain Sight: Drivers Impelling Agencies to Digitise | PAGE 2 Introduction 2020 is the year most of us would like to forget. Prolonged drought, horrific bushfires and floods followed by the outbreak of COVID-19 has led to estimates1 that the total level of debt under the Coalition Government will surpass $1 trillion1, creating an enduring deficit situation that will have implications for Federal and State agency administrative funding for years to come. The collective impact of this rolling wave of disasters has caused all Australian jurisdictions to rethink their business models, particularly with regard to services to citizens and businesses. The terms ‘pivot’ and ‘agility’ are now firmly embedded in the dialogue regarding the imagined post COVID-19 ‘new normal’. Front and centre of that pivot is the heightened emphasis on the digitisation of services to not only citizens, but also now to businesses. “The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has reminded us of the increasing reliance we have on technology in our day-to- day lives. -

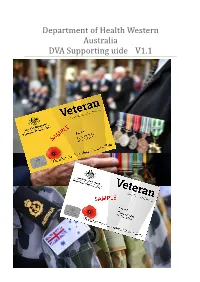

DVA Supporting Guide (PDF 854KB)

Department of Health Western Australia DVA Supporting uide V1.1 Table of Contents About ......................................................................................................................... 3 Valid Health treatment cards for financial authorisation determination ................... 6 Non-valid DVA cards for health treatment under Arrangement ............................... 6 Gold Card Holders .............................................................................................. 7 White Card Holders ............................................................................................. 8 DVA patient election form ....................................................................................... 9 Billing arrangements for selected services provided to DVA Entitled Persons . 9 Hospital transfer process for DVA Entitled Persons from public to private hospitals ................................................................................................................. 11 Inter-hospital transport arrangements for DVA Entitled Persons ...................... 13 Road Ambulance - DVA eligible patients post 1 July 2017 ............................... 15 Arrangements for the provision and charging of aids or equipment, home assessment and home modification for DVA Entitled Persons ......................... 18 Loan Equipment – Arrangements for the provision and charging for DVA Entitled Persons ..................................................................................................... 24 Community -

Submission to the Taskforce

ACCESS CARD CONSUMER AND PRIVACY TASKFORCE Discussion Paper Number 1: THE AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT HEALTH AND SOCIAL SERVICES ACCESS CARD 15 June 2006 THE ACCESS CARD CONSUMER AND PRIVACY TASKFORCE DISCUSSION PAPER NUMBER 1: THE AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT HEALTH AND SOCIAL SERVICES ACCESS CARD TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1—INTRODUCTION AND THE ROLE OF THE CONSUMER AND PRIVACY TASKFORCE ..................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction..................................................................................................................... 3 The Role of the Consumer and Privacy Taskforce ......................................................... 3 Discussion Paper Number 1—Outline............................................................................ 5 Part 2—THE GOVERNMENT’S ARGUMENT FOR THE ACCESS CARD ................. 7 The access card in brief................................................................................................... 7 The access card in detail ................................................................................................. 9 Benefits to consumers................................................................................................. 9 Improved Government service delivery.................................................................... 10 The form of the access card .......................................................................................... 11 What the access card will NOT be............................................................................... -

The Access Card – Fallacies and Facts

The Access Card – fallacies and facts Presentation by Anna Johnston, Chair, Australian Privacy Foundation PIAC Public Forum 9 November 2006, Sydney Good evening. I would like to thank PIAC for their invitation to address this forum on the so- called Access Card. By way of background, the Australian Privacy Foundation was formed in 1987, to fight the Australia Card proposal. We obviously won that campaign, and have since become the leading non-governmental organisation dedicated to protecting the privacy rights of Australians. We are opposed to the idea of a national identity card for Australians, but that is by no means the only issue we deal with. Relying entirely on volunteer effort and without government funding, we aim to focus public attention on emerging issues which pose a threat to the freedom and privacy of Australians. In the past year for example we have worked on issues as diverse as electronic health records, telecommunications privacy, the census, e-passports and workplace surveillance. 1 For more information about what we do, or to make a nomination for your favourite privacy invader for the 2006 Big Brother Awards, you can check out our website, at www.privacy.org.au I would also encourage you to look at our website for more information about the so-called Access Card. In particular, our comprehensive Information Paper on the proposal pulls together every public resource we can find, to explain exactly what we do and don’t know about the card, the chip, the database, and how the system will work. My comments tonight really only skim the surface of the issues and concerns presented in that paper. -

Whatever Happened to Frank and Fearless? the Impact of New Public Management on the Australian Public Service

Whatever Happened to Frank and Fearless? The impact of new public management on the Australian Public Service Whatever Happened to Frank and Fearless? The impact of new public management on the Australian Public Service Kathy MacDermott Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/frank_fearless_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: MacDermott, Kathy. Title: Whatever happened to frank and fearless? : the impact of the new public service management on the Australian public service / Kathy MacDermott. ISBN: 9781921313912 (pbk.) 9781921313929 (web) Series: ANZSOG series Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Civil service--Australia. Public administration--Australia. Australia--Politics and government. Dewey Number: 351.94 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher. Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2008 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University. He is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). He is also a joint appointment with the Department of Politics and Public Policy at Griffith University and a principal researcher with two research centres: the Governance and Public Policy Research Centre and the nationally- funded Key Centre in Ethics, Law, Justice and Governance at Griffith University. -

Digital Transformation Agency Annual Report 2019–20 Simple, Smart and User-Focused Government Services If You Have Questions About This Annual Report, Please Contact

Digital Transformation Agency Annual Report 2019–20 Simple, smart and user-focused government services If you have questions about this annual report, please contact: Digital Transformation Agency PO Box 457 Canberra ACT 2601 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dta.gov.au You can find a digital version of our annual report at: www.dta.gov.au ISSN 2208-6943 (Online) ISSN 2208-6951 (Print) © Digital Transformation Agency 2020 With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms and where otherwise noted, this product is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au), as is the full legal code for the licence (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ legalcode). The terms under which the Coat of Arms can be used are detailed on the following website: www.dpmc.gov.au/government/its-honour. This document must be attributed as the Digital Transformation Agency Annual Report 2019–20. Visual design by Digital Transformation Agency Layout by Keep Creative Printing by CanPrint Writing/editorial support by Cinden Lester Communications Digital Transformation Agency Annual Report 2019–20 Simple, smart and user-focused government services Digital Transformation Agency Annual Report 2019–20 Letter of transmittal The Hon Stuart Robert MP Minister for the National Disability Insurance Scheme Minister for Government Services Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister I am pleased to present the Digital Transformation Agency Annual Report 2019–20 for the year ended 30 June 2020. -

![Access Card” Data Base [Sydney Morning Herald 7 March 2007]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0753/access-card-data-base-sydney-morning-herald-7-march-2007-6530753.webp)

Access Card” Data Base [Sydney Morning Herald 7 March 2007]

Late submission by Dr Michael Head, Associate Professor of Law, University of Western Sydney The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) director Paul O’Sullivan has told the Senate committee that ASIO would not need a warrant to obtain information from to the national “access card” data base [Sydney Morning Herald 7 March 2007]. This statement underscores why this entire proposal should be rejected as a police- state measure. The response to ASIO’s statement by the Department of Human Services secretary Patricia Scott only confirms that the data base will be readily accessible by the intelligence and police agencies. She said that after talks between lawyers for ASIO and the department, ASIO could ask her department for access, and if refused, seek a search warrant [Above]. This testimony confirms that the Australian government is seeking to introduce a national identity card, thinly disguised as an “access” card needed to obtain public health and social services. In an unprecedented operation, the government plans a mass registration drive, starting early next year, to photograph and record the details of 16.7 million people—almost the entire adult population—by 2010. Prime Minister John Howard and his ministers claim that the access card is not an ID card—it will not be compulsory, nor will people have to carry it for identity purposes. But it will inevitably become a de facto ID card, complete with photo and identity number. From 2010, no one will be able to receive a pension or social security benefit, a child support payment, medical services under the Medicare health scheme or treatment in a public hospital without it. -

An Independent Review of Airport Security and Policing for the Government of Australia

An Independent Review of Airport Security and Policing for the Government of Australia by The Rt Hon Sir John Wheeler DL September 2005 © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 ISBN 1 921092 15 7 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth available from the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Commonwealth Copyright Administration Intellectual Property Branch Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts GPO Box 2154 Canberra ACT 2601 Online email: http://www.dcita.gov.au/cca ii Preface On 5th June, 2005, the former Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Transport and Regional Services, the Hon John Anderson MP, invited me to Head this Review into Airport Security and Policing. I subsequently liaised with the Department of Transport and Regional Services Secretary, Mr Michael Taylor, on the Terms of Reference for the Review and I have been engaged on the project since 7th June. My Review Team and I have visited a number of airports in Australia and it is upon the basis of these visits, research undertaken, the written submissions received and the detailed discussions that we have had, that I have developed my recommendations. My approach to the Review has included taking a fresh look at the decisions already made by the Australian Government, especially those of recent months. Thus, I support and comment upon matters such as the proposed appointment of the Airport Security Controller and the role of CCTV. -

Int Ccpr Ngo Aus 95 805

This submission to the Human Rights Committee has been prepared by the National Association of Community Legal Centres, the Human Rights Law Resource Centre and Kingsford Legal Centre, with substantial contributions from over 50 NGOs. This submission is supported, in whole or in part, by more than 200 NGOs across Australia. The National Association of Community Legal Centres is the peak body for over 200 community legal services across Australia. Each year, community legal centres provide free legal services, information and advice to over 250,000 disadvantaged Australians. The Human Rights Law Resource Centre is a national specialist human rights legal service. It aims to promote and protect human rights, particularly the human rights of people that are disadvantaged or living in poverty, through the practice of law. The Kingsford Legal Centre is a community legal centre in Sydney which provides free advice and ongoing assistance to members of community in relation to a number of areas of law, including discrimination law. Kingsford Legal Centre also undertakes law reform and community education work. This publication does not contain legal advice and you should seek professional advice before taking any action based on its contents. Kingsford Legal Centre Operated by the Law Faculty of the University of National Association of Community Legal Centres Human Rights Law Resource Centre Ltd New South Wales Suite 408, 379-383 Pitt Street Level 1, 550 Lonsdale Street Law Building Sydney NSW 2000 Melbourne VIC 3000 UNSW NSW 2052 E [email protected] T +61 2 9264 9595 E [email protected] T +61 3 9225 6695 E [email protected] T +61 2 9385 9566 F +61 3 9264 9594 www.naclc.org.au F+ 61 3 9225 6686 www.hrlrc.org.au F +61 2 9385 9583 www.kingsfordlegalcentre.org Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................................... -

Introducing Integrated E-Government in Australia

Introducing integrated e-government in Australia Arvo Ott, Fergus Hanson and Jelizaveta Krenjova Policy Brief Report No. 11/2018 Embargoed until 11.59pm, 29 November 2018 AEST. Media may report 30 November 2018. About the authors Dr Arvo Ott joined the e-Governance Academy, a non-profit think tank and consultancy organisation in Estonia, on 1 November 2005. His main responsibilities include the coordination of e-governance studies (e-government and e-democracy aspects), training programs and general management. Prior to joining the e-Governance Academy, Dr Ott served as the head of Department of State information systems (head of e-government office) at the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications for 12 years. He was responsible for Estonian information society and e-government strategy planning, and legal, organisational and technical architecture development and implementation. During the last several years, Dr Ott took part in many international projects and programs on e-governance (including information society policy and e-participation advice, e-government interoperability aspects, organisation development and planning). Fergus Hanson is the head of ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre. He is the author of Internet wars and has published widely in Australian and international media on a range of cyber and foreign policy topics. He was a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution and a Professional Fulbright Scholar based at Georgetown University working on the take-up of new technologies by the US Government. He has worked for the United Nations and as a program director at the Lowy Institute and served as a diplomat at the Australian Embassy in The Hague. -

Political Chronicles Commonwealth of Australia

Australian Journal of Politics and History: Volume 52, Number 4, 2006, pp. 637-689. Political Chronicles Commonwealth of Australia January to June 2006 JOHN WANNA The Australian National University and Griffith University The Liberal Ascendancy in the Governing Coalition With approximately twenty months to go before the next election, the Prime Minister, John Howard, decided it was time to refresh his ministry and give the government a new look. He was facing a constant barrage of speculation about his leadership intentions and, as Australia’s second longest-serving prime minister, he was yet to notch up ten years in the office (an anniversary that fell in March 2006 — see “the sweetest anniversary”, Weekend Australian, 25-26 February). The reputation of his government was also being damaged against the ever-worsening backdrop of the war in Iraq and the almost daily revelations emerging from the related Iraqi wheat scandal involving AWB Ltd (the former Australian Wheat Board) and a range of other government agencies. So, returning from his annual holidays, Howard took the opportunity to engineer a major ministerial reshuffle — a favoured tactic that was now becoming something of a pattern. To create room for the manoeuvre, Howard engineered three vacancies: Defence Minister, Senator Robert Hill, was retiring to take an ambassadorial post at the United Nations; the Families Minister, Senator Kay Paterson, resigned from the ministry; and Ian Macdonald (Fisheries, Forestry and Conservation Minister) was dropped from the outer ministry with Howard telling him he had no prospects of further promotion and should make way for younger members. In effect, Howard (aged almost sixty-seven) did to Macdonald (aged sixty) what Menzies had done in his day when offloading ministerial colleagues — telling ministers younger than himself that they had had a long enough innings and had no future in the ministry.