An Investigation Into the Phraseology of Question

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberal Women: a Proud History

<insert section here> | 1 foreword The Liberal Party of Australia is the party of opportunity and choice for all Australians. From its inception in 1944, the Liberal Party has had a proud LIBERAL history of advancing opportunities for Australian women. It has done so from a strong philosophical tradition of respect for competence and WOMEN contribution, regardless of gender, religion or ethnicity. A PROUD HISTORY OF FIRSTS While other political parties have represented specific interests within the Australian community such as the trade union or environmental movements, the Liberal Party has always proudly demonstrated a broad and inclusive membership that has better understood the aspirations of contents all Australians and not least Australian women. The Liberal Party also has a long history of pre-selecting and Foreword by the Hon Kelly O’Dwyer MP ... 3 supporting women to serve in Parliament. Dame Enid Lyons, the first female member of the House of Representatives, a member of the Liberal Women: A Proud History ... 4 United Australia Party and then the Liberal Party, served Australia with exceptional competence during the Menzies years. She demonstrated The Early Liberal Movement ... 6 the passion, capability and drive that are characteristic of the strong The Liberal Party of Australia: Beginnings to 1996 ... 8 Liberal women who have helped shape our nation. Key Policy Achievements ... 10 As one of the many female Liberal parliamentarians, and one of the A Proud History of Firsts ... 11 thousands of female Liberal Party members across Australia, I am truly proud of our party’s history. I am proud to be a member of a party with a The Howard Years .. -

Australian Parliamentary Delegation

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Australian Parliamentary Delegation to the Russian Federation and the Italian Republic 17 April – 1 May 2005 REPORT June 2005 ii © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 ISBN 0 642 71532 7 This document was printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. iii MEMBERS OF THE DELEGATION Leader Senator the Hon. Paul Calvert President of the Senate Senator for Tasmania Liberal Party of Australia Deputy Leader Ms Jill Hall, MP Member for Shortland (NSW) Australian Labor Party Members Senator Jacinta Collins Senator for Victoria Australian Labor Party Mrs Kay Elson, MP Member for Forde (QLD) Liberal Party of Australia Senator Jeannie Ferris Senator for South Australia Liberal Party of Australia The Hon. Jackie Kelly, MP Member for Lindsay (NSW) Liberal Party of Australia Senator Ross Lightfoot Senator for Western Australia Liberal Party of Australia Delegation secretary Mr John Vander Wyk Department of the Senate Private Secretary to the Mr Don Morris President of the Senate iv The delegation with the Archimandrite of the Holy Trinity-St Sergius Lavra monastery at Sergiev Posad, Father Savva. From left, the Deputy Head of Mission and Counsellor at the Australian Embassy, Mr Alex Brooking, Senator Jacinta Collins, Mrs Kay Elson, MP, Senator the Hon. Paul Calvert (Delegation Leader), Father Savva, Senator Ross Lightfoot, Senator Jeannie Ferris, the Hon. Jackie Kelly, MP, and Mrs Jill Hall (Deputy Leader). v TABLE OF CONTENTS MEMBERS OF THE DELEGATION iii PREFACE -

Fiftieth Parliament of New Zealand

FIFTIETH PARLIAMENT OF NEW ZEALAND ___________ HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ____________ LIST OF MEMBERS 7 August 2013 MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT Member Electorate/List Party Postal Address and E-mail Address Phone and Fax Freepost Parliament, Adams, Hon Amy Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings (04) 817 6831 Minister for the Environment Wellington 6160 (04) 817 6531 Minister for Communications Selwyn National [email protected] and Information Technology Associate Minister for Canter- 829 Main South Road, Templeton (03) 344 0418/419 bury Earthquake Recovery Christchurch Fax: (03) 344 0420 [email protected] Freepost Parliament, Ardern, Jacinda List Labour Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings (04) 817 9388 Wellington 6160 Fax: (04) 472 7036 [email protected] Freepost Parliament (04) 817 9357 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 437 6445 Ardern, Shane Taranaki–King Country National Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Auchinvole, Chris List National (04) 817 6936 Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament, Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings (04) 817 9392 Bakshi, Kanwaljit Singh National List Wellington 6160 Fax: (04) 473 0469 [email protected] Freepost Parliament Banks, Hon John Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Leader, ACT party Wellington 6160 Minister for Regulatory Reform [email protected] (04) 817 9999 Minister for Small Business ACT Epsom Fax -

"Unfair" Trade?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Garcia, Martin; Baker, Astrid Working Paper Anti-dumping in New Zealand: A century of protection from "unfair" trade? NZ Trade Consortium Working Paper, No. 39 Provided in Cooperation with: New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER), Wellington Suggested Citation: Garcia, Martin; Baker, Astrid (2005) : Anti-dumping in New Zealand: A century of protection from "unfair" trade?, NZ Trade Consortium Working Paper, No. 39, New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER), Wellington This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/66072 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

Blair (ALP 8.0%)

Blair (ALP 8.0%) Location South east Queensland. Blair includes the towns of Ipswich, Rosewood, Esk, Kilcoy and surrounding rural areas. Redistribution Gains Karana Downs from Ryan, reducing the margin from 8.9% to 8% History Blair was created in 1998. Its first member was Liberal Cameron Thompson, who was a backbencher for his entire parliamentary career. Thompson was defeated in 2007 by Shayne Neumann. History Shayne Neumann- ALP: Before entering parliament, Neumann was a lawyer. He was a parliamentary secretary in the Gillard Government and is currently Shadow Minister for Immigration. Robert Shearman- LNP: Michelle Duncan- Greens: Sharon Bell- One Nation: Bell is an estimating assistant in the construction industry. Majella Zimpel- UAP: Zimpel works in social services. Simone Karandrews- Independent: Karandrews is a health professional who worked at Ipswich Hospital. John Turner- Independent: Peter Fitzpatrick- Conservative National (Anning): John Quinn- Labour DLP: Electoral Geography Labor performs best in and around Ipswich while the LNP does better in the small rural booths. Labor’s vote ranged from 39.37% at Mount Kilcoy State School to 76.25% at Riverview state school near Ipswich. Prognosis Labor should hold on to Blair quite easily. Bonner (LNP 3.4%) Location Eastern suburbs of Brisbane. Bonner includes the suburbs of Mount Gravatt, Mansfield, Carindale, Wynnum, and Manly. Bonner also includes Moreton Island. Redistribution Unchanged History Bonner was created in 2004 and has always been a marginal seat. Its first member was Liberal Ross Vasta, who held it for one term before being defeated by Labor’s Kerry Rea. Rea only held Bonner for one term before being defeated by Vasta, running for the LNP. -

9 9 8.5 8.5 8 9 8.5 8 8 7 Roll Call

ROLL CALL – How Our MPs Performed In 2011 Trans Tasman’s Editors have once again run their rule over NZ’s MPs and rated their performance in 2011. Roll Call looks at how they’ve performed in Caucus, Cabinet, Committee, the House, their electorate and the influence they bring, or are likely, to bring to bear in their various forums. This year being election year, there are some MPs who are no longer with us, and a host of newcomers and some better known returnees, who are not rated, but on whom we have commented regarding what we know of them, and what to expect from them. As we are rating MPs for their 2011 performances, new Cabinet or shadow Cabinet roles are not included. Cabinet Ministers This 2010 Year’s Name Seat/list Responsibilities Comments Rating Rating Key, John Helensville Prime Minister, Minister of Tourism, As one of NZ’s most popular ever PMs, Key did Ministerial Services, Minister in Charge what was needed by his party and delivered of the NZ Security, Intelligence Service, National a second term based almost entirely Minister Responsible for the GCSB upon “Brand Key.” Some of the Teflon armour flaked off over the year and some of his strongest supporters wonder whether he has a plan beyond careful political management 9 9 and upsetting as few people as possible. In the House Key was comfortable most of the time, though once or twice he showed a mean streak. He took a bit of a battering during the campaign itself, but a win is a win is a win. -

Ready Programs and the Papulu CLC Director David Ross

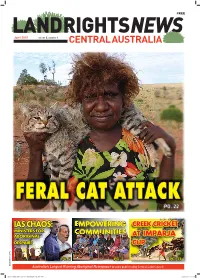

FREE April 2015 VOLUME 5. NUMBER 1. PG. ## FERAL CAT ATTACK PG. 22 IAS CHAOS: EMPOWERING CREEK CRICKET MINISTERS FOR COMMUNITIES ABORIGINAL AT IMPARJA DESPAIR? CUP PG. 2 PG. 2 PG. 33 ISSN 1839-5279 59610 CentralLandCouncil CLC Newspaper 36pp Alts1.indd 1 10/04/2015 12:32 pm NEWS Aboriginal Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion confronts an EDITORIAL angry crowd at the Alice Springs Convention Centre. Land Rights News Central He said organisations got the funding they deserved. Australia is published by the Central Land Council three times a year. The Central Land Council 27 Stuart Hwy Alice Springs NT 0870 tel: 89516211 www.clc.org.au email [email protected] Contributions are welcome SUBSCRIPTIONS Land Rights News Central Australia subscriptions are $20 per year. LRNCA is distributed free to Aboriginal organisations and communities in Central Australia Photo courtesy CAAMA To subscribe email: [email protected] IAS chaos sparks ADVERTISING Advertise in the only protests and probe newspaper to reach Aboriginal people THE AUSTRALIAN Senate will inquire original workers. Neighbouring Barkly Regional Council re- into the delayed and chaotic funding round Nearly half of the 33 organisations sur- ported 26 Aboriginal job losses as a result of in remote Central of the new Indigenous advancement scheme veyed by the Alice Springs Chamber of Com- a 35% funding cut to community services in a (IAS), which has done as much for the PM’s merce were offered less funding than they had UHJLRQWURXEOHGE\SHWUROVQLI¿QJ Australia. reputation in Aboriginal Australia as his way previously for ongoing projects. President Barb Shaw told the Tennant with words. -

Senate Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES Senate Official Hansard No. 18, 2005 WEDNESDAY, 30 NOVEMBER 2005 FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—FOURTH PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE INTERNET The Journals for the Senate are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/work/journals/index.htm Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard For searching purposes use http://parlinfoweb.aph.gov.au SITTING DAYS—2005 Month Date February 8, 9, 10 March 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, 15, 16, 17 May 10, 11, 12 June 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, 23 August 9, 10, 11, 16, 17, 18 September 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15 October 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13 November 3, 7, 8, 9, 10, 28, 29, 30 December 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 103.9 FM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM GOSFORD 98.1 FM BRISBANE 936 AM GOLD COAST 95.7 FM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 747 AM NORTHERN TASMANIA 92.5 FM DARWIN 102.5 FM FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—FOURTH PERIOD Governor-General His Excellency Major-General Michael Jeffery, Companion in the Order of Australia, Com- mander of the Royal Victorian Order, Military Cross Senate Officeholders President—Senator the Hon. Paul Henry Calvert Deputy President and Chairman of Committees—Senator John Joseph Hogg Temporary Chairmen of Committees—Senators Guy Barnett, George Henry Brandis, Hedley Grant Pearson Chapman, Patricia Margaret Crossin, Alan Baird Ferguson, Michael George Forshaw, Stephen Patrick Hutchins, Linda Jean Kirk, Philip Ross Lightfoot, Gavin Mark Mar- shall, Claire Mary Moore, Andrew James Marshall Murray, Hon. -

House of Representatives List of Members

FORTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT OF NEW ZEALAND ___________ HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ____________ LIST OF MEMBERS 1 September 2008 MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT Member Electorate/List Party Postal Address and E-mail Address Phone and Fax Anderton, Hon Jim Freepost Parliament, (04) 470 6550 Leader, Progressive Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 495 8441 Minister of Agriculture Wellington 6160 Minister for Biosecurity Minister of Fisheries Wigram Progressive [email protected] Minister of Forestry Minister responsible for the 296 Selwyn St, Spreydon, Christchurch (03) 365 5459 Public Trust PO Box 33 164, Barrington, Christchurch Fax (03) 365 6173 Associate Minister of Health [email protected] Associate Minister for Tertiary Education Freepost Parliament (04) 471 9357 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 437 6447 Ardern MP, Shane Taranaki – King Country National Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament (04) 470 6936 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 439 6445 Auchinvole, Chris List National Wellington 6160 [email protected] (04) 470 6572 Barker, Hon Rick Freepost Parliament Fax (04) 472 8036 Minister of Internal Affairs Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Minister of Civil Defence Wellington 6160 Minister for Courts List Labour [email protected] Minister of Veterans’ Affairs Associate Minister of Justice PO Box 1245, Hastings (06) 876 8966 Fax (06) 876 4908 Freepost Parliament (04) 471 9906 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) -

Activist #10, 2009

Rail & Maritime Transport Union Volume ISSUE # 101010 Published Regularly - ISSN 1178-7392 (Print & Online) 1 May 2009 LATEST STATS – UNEMPLOYMENT SHAREHOLDERS ELIGIBLE FOR BENEFIT COMPENSATION FROM TRANZ RAIL Latest statistics released shows that at the CASE end of March 2009, 37,000 working aged A list of the shareholders who are eligible for people (aged 18-64 years) were receiving compensation from the Tranz Rail insider is an Unemployment Benefit. Over the year available from the following Securities to March 2009, the number of recipients of Commission of NZ website link; an Unemployment Benefit increased by 18,000, or 95 percent. The link to the info http://www.seccom.govt.nz/tranz-rail-share- sheet is; refund.shtml#K http://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/abou Shareholders on this list can contact Geoff t-msd-and-our- work/newsroom/factsheets/benefit/2009 Brown on (04) 471 8295 or email /fact-sheet-ub-09-mar-31.doc [email protected] for information about how to claim their compensation. MAY DAY Claimants will need to verify their identity and shareholding details. They should May Day is celebrated and recognized as contact the Commission no later than 24 July the International Workers’ day, chosen over 2009 so that compensation can be paid. 100 years ago to commemorate the struggles and gains of workers and the labour PORTS FORUM movement. Most notable An interesting and reasons to celebrate are challenging programme the 8-hour day, is in store for delegates Saturday as part of the attending the 2009 weekend, improved National Ports Forum in working conditions and Wellington on 5 & 6 child labor laws. -

New Zealand Hansard Precedent Manual

IND 1 NEW ZEALAND HANSARD PRECEDENT MANUAL Precedent Manual: Index 16 July 2004 IND 2 ABOUT THIS MANUAL The Precedent Manual shows how procedural events in the House appear in the Hansard report. It does not include events in Committee of the whole House on bills; they are covered by the Committee Manual. This manual is concerned with structure and layout rather than text - see the Style File for information on that. NB: The ways in which the House chooses to deal with procedural matters are many and varied. The Precedent Manual might not contain an exact illustration of what you are looking for; you might have to scan several examples and take parts from each of them. The wording within examples may not always apply. The contents of each section and, if applicable, its subsections, are included in CONTENTS at the front of the manual. At the front of each section the CONTENTS lists the examples in that section. Most sections also include box(es) containing background information; these boxes are situated at the front of the section and/or at the front of subsections. The examples appear in a column format. The left-hand column is an illustration of how the event should appear in Hansard; the right-hand column contains a description of it, and further explanation if necessary. At the end is an index. Precedent Manual: Index 16 July 2004 IND 3 INDEX Absence of Minister see Minister not present Amendment/s to motion Abstention/s ..........................................................VOT3-4 Address in reply ....................................................OP12 Acting Minister answers question......................... -

Public Forum 11 November 2015

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 12th Assembly Public Accounts Committee Inquiry into Funding of Rugby League Facilities in Darwin Public Forum Transcript 5.00 pm, Wednesday, 11 November 2015 Litchfield Room, Parliament House Members: Mrs Robyn Lambley, MLA, Chair, Member for Araluen Ms Natasha Fyles, MLA, Member for Nightcliff Ms Nicole Manison, MLA, Member for Wanguri Mr Gerry Wood, MLA, Member for Nelson Witnesses: Brad and Cherill Hopkins Michael Hawkes Inge van Sprang Jude Scott Ron Grolep Margaret Clinch Jennie Renfree Rollo Manning Robyn MacGillivray Ian McNeill Karen O’Dwyer Public Accounts Committee – Inquiry into Funding of Rugby League Facilities in Darwin Madam CHAIR: I welcome everyone here this evening to the inquiry into Richardson Park by the Public Accounts Committee. It is great of you to come along at such short notice; I think most of you were only advised of this yesterday. We decided it was important for local residents affected by the upgrade to Richardson Park to have an opportunity to talk to us. We will have a fairly informal approach to this afternoon; we want to listen to what you have to say. We can give a little feedback from what we have heard and have been able to glean from the documentation provided to the committee today. I ask that you be mindful of the fact this is a formal proceedings as a public hearing; it is being webcast through the Assembly’s website. A transcript will be made for use of the committee and may be put on the committee’s website. That is not to deter you from being frank and open, if that is what you want to be.