Early Medieval Buckinghamshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Bucks Rripple (Ramblers Repairing & Improving Public Paths

North Bucks rRIPPLE (ramblers Repairing & Improving Public Paths for Leisure & Exercise) Activity Report 22 September 2016 – 13 November 2016 Before & after photos of all work are available on request. Man hours include some travel time. DaG = Donate a Gate. CAMS is a reference used by BCC/Ringway Jacobs for work requests. All work is requested and authorised by Alastair McVail, Ringway Jacobs, North Bucks RoW Officer, or Jon Clark, BCC Access Officer. 22/9/16 Took delivery of 7 Marlow and 3 Woodstock kissing gates from BCC/TfB at CRFC. Good chat with Greg & Bill of TfB regarding gate installation and their preferred installation method using a timber post attached to either side of a gate. Not so critical with kissing gates. 22/9/16 Stewkley. Emailed Alastair McVail re the replacement by TfB of our gate with a kissing gate at SP842264 to appease Mrs Carter. (See 9/8/16 CAMS 81198). 23/9/16 Eythrop. Emailed Jon Clark reCAMS 81845 at SP768134 completed on 3/2/16 as way marker has been knocked down again. 26/9/16 Eythrop. Received CAMS 83629 at SP768134 to rerect snapped of at ground level way marker post - hit by a vehicle. 27/9/16 Mentmore. CAMS 82567 at SP907186 on MEN/8/1 installed way mark post and bridleway way marker discs. Liaised with golf club groundsman, Adam. Two x 2.5 = 5.0 man hours. B&J. 27/9/16 Mentmore. CAMS 82569 at SP889192 and at SP892194 on MEM/15/2. Checked functioning of two timber kissing gates. First one needed timber attaching to post to prevent gate from swinging right through, second considered to be okay. -

The Hidation of Buckinghamshire. Keith Bailey

THE HIDA TION OF BUCKINGHAMSHIRE KEITH BAILEY In a pioneering paper Mr Bailey here subjects the Domesday data on the hidation of Buckinghamshire to a searching statistical analysis, using techniques never before applied to this county. His aim is not explain the hide, but to lay a foundation on which an explanation may be built; to isolate what is truly exceptional and therefore calls for further study. Although he disclaims any intention of going beyond analysis, his paper will surely advance our understanding of a very important feature of early English society. Part 1: Domesday Book 'What was the hide?' F. W. Maitland, in posing purposes for which it may be asked shows just 'this dreary old question' in his seminal study of how difficult it is to reach a consensus. It is Domesday Book,1 was right in saying that it almost, one might say, a Holy Grail, and sub• is in fact central to many of the great questions ject to many interpretations designed to fit this of early English history. He was echoed by or that theory about Anglo-Saxon society, its Baring a few years later, who wrote, 'the hide is origins and structures. grown somewhat tiresome, but we cannot well neglect it, for on no other Saxon institution In view of the large number of scholars who have we so many details, if we can but decipher have contributed to the subject, further discus• 2 them'. Many subsequent scholars have also sion might appear redundant. So it would be directed their attention to this subject: A. -

1 Buckinghamshire; a Military History by Ian F. W. Beckett

Buckinghamshire; A Military History by Ian F. W. Beckett 1 Chapter One: Origins to 1603 Although it is generally accepted that a truly national system of defence originated in England with the first militia statutes of 1558, there are continuities with earlier defence arrangements. One Edwardian historian claimed that the origins of the militia lay in the forces gathered by Cassivelaunus to oppose Caesar’s second landing in Britain in 54 BC. 1 This stretches credulity but military obligations or, more correctly, common burdens imposed on able bodied freemen do date from the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of the seventh and eight centuries. The supposedly resulting fyrd - simply the old English word for army - was not a genuine ‘nation in arms’ in the way suggested by Victorian historians but much more of a selective force of nobles and followers serving on a rotating basis. 2 The celebrated Burghal Hidage dating from the reign of Edward the Elder sometime after 914 AD but generally believed to reflect arrangements put in place by Alfred the Great does suggest significant ability to raise manpower at least among the West Saxons for the garrisoning of 30 fortified burghs on the basis of men levied from the acreage apportioned to each burgh. 3 In theory, it is possible that one in every four of all able-bodied men were liable for such garrison service. 4 Equally, while most surviving documentation dates only from 1 G. J. Hay, An Epitomised History of the Militia: The Military Lifebuoy, 54 BC to AD 1905 (London: United Services Gazette, 1905), 10. -

Post-Medieval and Modern Resource Assessment

THE SOLENT THAMES RESEARCH FRAMEWORK RESOURCE ASSESSMENT POST-MEDIEVAL AND MODERN PERIOD (AD 1540 - ) Jill Hind April 2010 (County contributions by Vicky Basford, Owen Cambridge, Brian Giggins, David Green, David Hopkins, John Rhodes, and Chris Welch; palaeoenvironmental contribution by Mike Allen) Introduction The period from 1540 to the present encompasses a vast amount of change to society, stretching as it does from the end of the feudal medieval system to a multi-cultural, globally oriented state, which increasingly depends on the use of Information Technology. This transition has been punctuated by the protestant reformation of the 16th century, conflicts over religion and power structure, including regicide in the 17th century, the Industrial and Agricultural revolutions of the 18th and early 19th century and a series of major wars. Although land battles have not taken place on British soil since the 18th century, setting aside terrorism, civilians have become increasingly involved in these wars. The period has also seen the development of capitalism, with Britain leading the Industrial Revolution and becoming a major trading nation. Trade was followed by colonisation and by the second half of the 19th century the British Empire included vast areas across the world, despite the independence of the United States in 1783. The second half of the 20th century saw the end of imperialism. London became a centre of global importance as a result of trade and empire, but has maintained its status as a financial centre. The Solent Thames region generally is prosperous, benefiting from relative proximity to London and good communications routes. The Isle of Wight has its own particular issues, but has never been completely isolated from major events. -

Front Matter (PDF)

GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON MEMOIR No. 2 GEOLOGICAL RESULTS OF PETROLEUM EXPLORATION IN BRITAIN I945-I957 BY NORMAN LESLIE FALCON, M.A.F.1K.S. (CHIEF GEOLOGIST, THE BRITISH PETROLEUM COMPANY LIMITED) AND PERCY EDWARD KENT, D.Sc., Ph.D. (GEOLOGICAL ADVISER, BP EXPLORATXON [CANADA]) LONDON 4- AUGUST, I960 LIST OF PLATES PLATE I, FIG. 1. Hypothetical section through Kingsclere and Faringdon borings. (By R. G. W. BRU~STRO~) 2. Interpretative section through Fordon No. 1. Based on seismic reflection and drilling results, taking into account the probability of faulting of the type exposed in the Howardian Hills Jurassic outcrop. II. Borehole sections in West Yorkshire. (By A. P. TERRIS) III. Borehole sections in the Carboniferous rocks of Scotland. IV. Type column of the Upper Carboniferous succession in the Eakring area, showing lithological marker beds. (By M. W. STI~O~C) V. Structure contour map of the Top Hard (Barnsley) Seam in the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Coalfield. Scale : 1 inch to 2 miles. LIST OF TABLES Data from exploration wells, 1945-1957, m-- TABLE I. Southern England and the South Midlands II. The East Midlands III. East and West Yorkshire IV. Lancashire and the West Midlands V. Scotland LIST OF FIGURES IN THE TEXT Page Fig. 1. General map of areas explored to the end of 1957 6 2. Arreton : gravity residuals and reflection contours . 8 Ashdown : seismic interpretation of structure after drilling. Depths shown are of Great Oolite below sea,level 9 4. Mesozoic borehole sections in southern England 10 5. Faringdon area : gravity residuals and seismic refraction structure 14 6. -

Aylesbury Vale WCS Granborough CP

Aylesbury Vale District Granborough CP Aylesbury Vale District Parish Boundaries Development Sites Winslow Proposed Development Sites Surface Water WFD Surface Water Classifications High Good Moderate Poor Swanbourne CP Bad Groundwater Superficial Aquifers Secondary (undifferentiated) Secondary A Unproductive Granborough CP Bedrock Aquifers Principal Secondary (undifferentiated) Secondary A Secondary B Unproductive Source Protection Zones Zone 1 - Inner Protection Zone Zone 2 - Outer Protection Zone Zone 3 - Total Catchment Aylesbury Vale WCS Water Constraints Oving CP and Opportunities 0 0.2 0.4 0.8 Km Contains Ordnance Survey data (c) Crown copyright and database right 2016 Aylesbury Vale District Great Horwood CP Aylesbury Vale District Nash CP Parish Boundaries Development Sites Whaddon CP Proposed Development Sites Surface Water WFD Surface Water Classifications High Good Moderate Poor Bad Groundwater Superficial Aquifers Secondary (undifferentiated) Great Horwood CP Secondary A Unproductive Adstock CP Bedrock Aquifers Principal Little Horwood CP Secondary (undifferentiated) Secondary A Secondary B Unproductive Source Protection Zones Zone 1 - Inner Protection Zone Zone 2 - Outer Protection Zone Zone 3 - Total Catchment Aylesbury Vale WCS Water Constraints Swanbourne CP and Opportunities Winslow 0 0.3 0.6 1.2 Km Contains Ordnance Survey data (c) Crown copyright and database right 2016 Aylesbury Vale District Grendon Underwood CP Steeple Claydon CP Aylesbury Vale District Parish Boundaries Development Sites Proposed Development Sites -

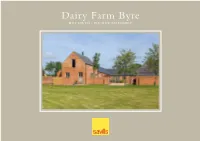

Dairy Farm Byre HILLESDEN • BUCKINGHAMSHIRE View from the Front of the House

Dairy Farm Byre HILLESDEN • BUCKINGHAMSHIRE View from the front of the house Dairy Farm Byre HILLESDEN • BUCKINGHAMSHIRE Approximate distances: Buckingham 3 miles • M40 (J9) 9 miles • Bicester 9 miles Brackley 10 miles • Milton Keynes 14 miles • Oxford 18 miles. Recently renovated barn, providing flexible accommodation in an enviable rural location Entrance hall • cloakroom • kitchen/breakfast room Utility/boot room • drawing/dining room • study Master bedroom with dressing room and en suite bathroom Bedroom two and shower room • two further bedrooms • family bathroom Ample off road parking • garden • car port SAVILLS BANBURY 36 South Bar, Banbury, Oxfordshire, OX16 9AE 01295 228 000 [email protected] Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text DESCRIPTION Entrance hall with double faced wood burning stove,(to kitchen and entrance hall) oak staircase to first floor, under stairs cupboard and limestone flooring with underfloor heating leads through to the large kitchen/breakfast room. Beautifully presented kitchen with bespoke units finished with Caesar stone work surfaces. There is a Britannia fan oven, 5 ring electric induction hob, built in fridge/freezer. Walk in cold pantry with built in shelves. East facing oak glass doors lead out onto the front patio capturing the morning sun creating a light bright entertaining space. Utility/boot room has easy access via a stable door, to the rear garden and bbq area, this also has limestone flooring. Space for washing machine and tumble dryer. Steps up to the drawing/dining room with oak flooring, vaulted ceiling and exposed wooden beam trusses. This room has glass oak framed doors leading to the front and rear west facing garden. -

Ridge View, 1 Fleet Marston Cottages, Fleet Marston, Buckinghamshire, HP18 0PZ

Ridge View, 1 Fleet Marston Cottages, Fleet Marston, Buckinghamshire, HP18 0PZ Aylesbury 1.5 miles (Marylebone 55 mins.), Thame 10 miles, Milton Keynes 18 miles (Distances approx.) RIDGE VIEW, 1 FLEET MARSTON COTTAGES, FLEET MARSTON, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE HP18 0PZ A REFURBISHED COTTAGE EXTENDED OVER TIME TO NOW PROVIDE SIZEABLE ACCOMMODATION IN A QUARTER OF AN ACRE PLOT. RURAL LOCATION WITH FAR REACHING VIEWS JUST TWO MILES FROM AYLESBURY AND FIVE MINUTES FROM AYLESBURY VALE PARKWAY STATION. WADDESDON SCHOOL CATCHMENT Entrance Hall, Large Open Plan Sitting Room, Wonderful Garden Room, Kitchen/Dining Room, Cloakroom, Utility Room, Master Bedroom with Dressing Area and Bathroom, Three Further Double Bedrooms, Family Bathroom, Driveway Parking, Garage, Large Garden Backing onto Countryside Guide Price £485,000 Freehold LOCATION DESCRIPTION Marston comes from the words ‘Mersc and Tun’ meaning Marsh Ridge View is situated in a rural location with open countryside to the Farm. The epithet Fleet refers to a ‘Fleet’ of Brackish water. rear and superb views. The property dates from the late 1900’s and Fleet Marston is a small hamlet of houses either side of the A41 near has been greatly extended over the years, the most recent addition an Aylesbury with an early fourteenth century church. Although excellent garden room which really opens up the ground floor. The slightly larger now ‘Magna Britannia’ from 1806 states only 22 accommodation is very well presented, the current owners having inhabitants living in four houses. Waddesdon (2 ½ miles) has a shop undertaken refurbishment throughout. In the entrance hall are for day to day needs or alternatively Aylesbury is also 2 miles, with floorboards and the staircase, off to the side a cloakroom. -

Historic Walk-Thame-U3A-Draft 4

Historic Walk – Thame & District U3A This rural walk along the River Thame passes through a number of villages of historical interest and visits the 15th century architectural gems of Rycote Chapel and Waterstock Mill. Starting at the church at Shabbington in Buckinghamshire the route soon crosses the River Thame into Oxfordshire and follows the river, before crossing the old railway line to reach Rycote Chapel. From Rycote the route follows an undulating track to Albury and then on to Tiddington. Heading south in Tiddington the route circles west to cross the railway line again before arriving at Waterstock via the golf course. Here there is an opportunity to visit the old mill before returning via the 17th century bridge at Ickford and back into Buckinghamshire. The small hamlet of Little Ickford is the last port of call before returning across the fields to Shabbington. In winter the conditions underfoot can be muddy and in times of flood parts of the route are impassable. Walk Length The main walk (Walk A) is just over 8.5 miles (13.8 km) long (inclusive of two detours to Rycote Chapel and Waterstock Mill) and is reasonably flat. At a medium walking pace this should take 3.5 to 4 hours but time needs to be added on to appreciate the points of interest along the way. Walk B is 5.8 miles (9.4 km) a shorter version of Walk A, missing out some of Tiddington and Waterstock. Walk C is another shorter variation of 4.7 miles (7.5 km), taking in Ickford Bridge, Albury and Waterstock but missing out Rycote Chapel and Shabbington. -

BUCKING HAMS HIRE. [KBLLY's

46 LITTLR BRICKHILL. BUCKING HAMS HIRE. [KBLLY's 2Jth, r644. There is a record of the vicars of this Duke of Buckingham, killed a.t Northampton, 27 July, parish from the year 1'227 to r8go. The living is a 1460, Sir Henry Marney kt. 1st baron Marney, d. 24 titular vicarage, net yearly value £r6o, in the gift May, 1523, William Carey, Sir Thomas Neville Abdy of the Bishop of Oxford, and held since 1906 by the hart. d. 20 July, r877, Sir Charles Duncombe kt. d. Rev. Louis J ones B. A. of Christ's College, Cambridge. 17II, Sir William Rose, Lord Strathnairn and Admiral This village was formerly the first place in the county at Douglas. The manorial rights have ceased; the wb.ich the judges arrived on going the Norfolk circuit, present owner of the manor is Lieut.-Col. Alexander and from 1433 to r638 the a.ssizes and genexal gaol Finlay. The Duke of Bedford K.G. and Sir Ever<J,rd deliveries for Bucks were held here on aooount of its P. D. Pauncefort-Duncombe hart. of Brickhill Manor, beirug the nearsst spot in Buck..s to the metropolis, with also have property in the parish. The situation of this a good road and accommodation for man and horse ; in village on the highest part of the Brickhills Cfr. Saxton's map af 1574, it is marked as an assize town, Briehelle) and adjoining the Woburn plantations is and election as well at~ othsr county meetings were a.l!ro picturesque and eminently healthy. -

Archaeological Watching Brief Report at All Saints

ARCHAEOLOGICAL WATCHING BRIEF REPORT AT ALL SAINTS’ CHURCH, HILLESDEN, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE (NGR SP 68570 28755) On behalf of PCC All Saints Hillesden APRIL 2016 John Moore HERITAGE SERVICES All Saints Church, Hillesden, Buckinghamshire. HIAS 16. Archaeological Watching Brief Report REPORT FOR PCC All Saints Hillesden c/o Montgomery Architects 8 St Aldates Oxford OX1 1BS PREPARED BY Paul Murray ILLUSTRATION BY Autumn Robson EDITED BY John Moore AUTHORISED BY John Moore FIELDWORK 2nd – 10th March 2016 REPORT ISSUED 18th April 2016 ENQUIRES TO John Moore Heritage Services Hill View Woodperry Road Beckley Oxfordshire OX3 9UZ Tel: 01865 358300 Email: [email protected] JMHS Project No: 3498 Site Code: HIAS 16 Archive Location: The archive currently is maintained by John Moore Heritage Services and will be transferred to Buckinghamshire Museum Service under accession number: awaited i John Moore HERITAGE SERVICES All Saints Church, Hillesden, Buckinghamshire. HIAS 16. Archaeological Watching Brief Report CONTENTS Page SUMMARY 1 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Site Location and Geology 1 1.2 Historical and Archaeological Background 1 2 STRATEGY 3 2.1 Objectives 3 2.2 Methodology 3 3 RESULTS 4 4 FINDS AND ENVIRONMENTAL 11 5 DISCUSSION 11 6 BIBLIOGRAPHY 12 FIGURES Figure 1. Site location 2 Figure 2. Sections 5 Figure 3. Burials 7 PLATES Plate 1. Service Trench 6 Plate 2. Inhumation No 20 9 Plate 3. Service Pit 10 Plate 4. Tower Foundations (15) 10 Plate 5. Tower Foundations (18) 11 APPENDIXES Appendix A. Table 1, Context Inventory 13 ii John Moore HERITAGE SERVICES All Saints Church, Hillesden, Buckinghamshire. HIAS 16. Archaeological Watching Brief Report Summary John Moore Heritage Services were appointed by Montgomery Architects on behalf of PCC All Saints Hillesden to record and exhume three inhumations revealed during the excavation of service and soakaway trenchs at All Saints’ Church, Hillesden, Buckinghamshire. -

Local Priorities

APPENDIX A Wendover Local Area Forum Local Priorities 2014 Wendover Local Area Forum (LAF) invited its Youth Forum to run its local priorities process which involved consulting with residents to see if the LAF should revise its local priorities. Residents in the local area parishes (Aston Clinton, Buckland, Drayton Beauchamp, Halton, Stoke Mandeville, Wendover and Weston Turville) were surveyed and invited to rank their priorities and provide comment on the reasons behind these rankings. The local priorities budget will be allocated to the top actionable local priorities, subject to agreement by the Wendover Parish Council provided a stand at Wendover LAF, so over the next two years work Market. Here the young people are joined by local MP, can be undertaken to take forward David Lidington. projects and schemes to address these priorities. Another aspiration of this project Doing this project has helped me to understand was to enable the Youth Forum to play the needs in the community. I met people that lived in my area that I didn’t know. The things a wider role in the LAF and also to take that we have worked on in the forum have made a lead in the local democratic process. a difference and we can see things starting to Wendover Local Area Forum is happen. Because of the Youth Forum, I got to represent also the first to devolve a budget to its young people across the area and share my Youth Forum to work on the priority: thoughts and ideas with BCC Youth Service, Activities and facilities for young which affects things for the future.