Comics in American Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Representing Heroes, Villains and Anti- Heroes in Comics and Graphic

H-Film CFP: Who’s Bad? Representing Heroes, Villains and Anti- Heroes in Comics and Graphic Narratives – A seminar sponsored by the ICLA Research Committee on Comic Studies and Graphic Narratives Discussion published by Angelo Piepoli on Wednesday, September 7, 2016 This is a Call for Papers for a proposed seminar to be held as part of the American Comparative Literature Association's 2017 Annual Meeting. It will take place at Utrecht University in Utrecht, the Netherlands on July 6-9, 2017. Submitters are required to get a free account on the ACLA's website at http://www.acla.org/user/register . Abstracts are limited to 1500 characters, including spaces. If you wish to submit an astract, visit http://www.acla.org/node/12223 . The deadline for paper submission is September 23, 2016. Since the publication of La vida de Lazarillo de Tormes y de sus fortuna y adversidades in 1554, the figure of the anti-hero, which had originated in Homeric literature, has had great literary fortune over the centuries. Satan as the personification of evil, then, was the most interesting character in Paradise Lost by John Milton and initiated a long series of fascinating literary villains. It is interesting to notice that, in a large part of the narratives of these troubled times we are living in, the protagonist of the story is everything but a hero and the most acclaimed characters cross the moral borders quite frequently. This is a fairly common phenomenon in literature as much as in comics and graphic narratives. The advent of the Modern Age of Comic Books in the U.S. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime

SAN DIEGO PUBLIC LIBRARY PATHFINDER Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime The Central Library has a large collection of comics, the Usual Extra Rarities, 1935–36 (2005) by George graphic novels, manga, anime, and related movies. The Herriman. 741.5973/HERRIMAN materials listed below are just a small selection of these items, many of which are also available at one or more Lions and Tigers and Crocs, Oh My!: A Pearls before of the 35 branch libraries. Swine Treasury (2006) by Stephan Pastis. GN 741.5973/PASTIS Catalog You can locate books and other items by searching the The War Within: One Step at a Time: A Doonesbury library catalog (www.sandiegolibrary.org) on your Book (2006) by G. B. Trudeau. 741.5973/TRUDEAU home computer or a library computer. Here are a few subject headings that you can search for to find Graphic Novels: additional relevant materials: Alan Moore: Wild Worlds (2007) by Alan Moore. cartoons and comics GN FIC/MOORE comic books, strips, etc. graphic novels Alice in Sunderland (2007) by Bryan Talbot. graphic novels—Japan GN FIC/TALBOT To locate materials by a specific author, use the last The Black Diamond Detective Agency: Containing name followed by the first name (for example, Eisner, Mayhem, Mystery, Romance, Mine Shafts, Bullets, Will) and select “author” from the drop-down list. To Framed as a Graphic Narrative (2007) by Eddie limit your search to a specific type of item, such as DVD, Campbell. GN FIC/CAMPBELL click on the Advanced Catalog Search link and then select from the Type drop-down list. -

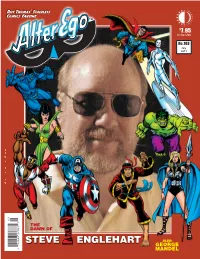

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals By

Comics Aren’t Just For Fun Anymore: The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals by David Recine A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in TESOL _________________________________________ Adviser Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date University of Wisconsin-River Falls 2013 Comics, in the form of comic strips, comic books, and single panel cartoons are ubiquitous in classroom materials for teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL). While comics material is widely accepted as a teaching aid in TESOL, there is relatively little research into why comics are popular as a teaching instrument and how the effectiveness of comics can be maximized in TESOL. This thesis is designed to bridge the gap between conventional wisdom on the use of comics in ESL/EFL instruction and research related to visual aids in learning and language acquisition. The hidden science behind comics use in TESOL is examined to reveal the nature of comics, the psychological impact of the medium on learners, the qualities that make some comics more educational than others, and the most empirically sound ways to use comics in education. The definition of the comics medium itself is explored; characterizations of comics created by TESOL professionals, comic scholars, and psychologists are indexed and analyzed. This definition is followed by a look at the current role of comics in society at large, the teaching community in general, and TESOL specifically. From there, this paper explores the psycholinguistic concepts of construction of meaning and the language faculty. -

Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko

Law Text Culture Volume 16 Justice Framed: Law in Comics and Graphic Novels Article 10 2012 Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Swinburne University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Bainbridge, Jason, Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko, Law Text Culture, 16, 2012, 217-242. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Abstract The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. This relationship has also informed superhero comics themselves – going all the way back to Superman’s debut in Action Comics 1 (June 1938). As DC President Paul Levitz says of the development of the superhero: ‘There was an enormous desire to see social justice, a rectifying of corruption. Superman was a fulfillment of a pent-up passion for the heroic solution’ (quoted in Poniewozik 2002: 57). This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Spider-Man, The Question and the Meta-Zone: Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Bainbridge Introduction1 The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Manga As a Teaching Tool 1

Manga as a Teaching Tool 1 Manga as a Teaching Tool: Comic Books Without Borders Ikue Kunai, California State University, East Bay Clarissa C. S. Ryan, California State University, East Bay Proceedings of the CATESOL State Conference, 2007 Manga as a Teaching Tool 2 Manga as a Teaching Tool: Comic Books Without Borders The [manga] titles are flying off the shelves. Students who were not interested in EFL have suddenly become avid readers ...students get hooked and read [a] whole series within days. (E. Kane, personal communication, January 17, 2007) For Americans, it may be difficult to comprehend the prominence of manga, or comic books, East Asia.1. Most East Asian nations both produce their own comics and publish translated Japanese manga, so Japanese publications are popular across the region and beyond. Japan is well-known as a highly literate society; what is less well-known is the role that manga plays in Japanese text consumption (Consulate General of Japan in San Francisco). 37% of all publications sold in Japan are manga of one form or another, including monthly magazines, collections, etc. (Japan External Trade Organization [JETRO], 2006). Although Japan has less than half the population of the United States, manga in all formats amounted to sales within Japan of around 4 billion dollars in 2005 (JETRO, 2006). This total is about seven times the United States' 2005 total comic book, manga, and graphic novel sales of 565 million dollars (Publisher's Weekly, 2007a, 2007b). Additionally, manga is closely connected to the Japanese animation industry, as most anime2 television series and films are based on manga; manga also provides inspiration for Japan's thriving video game industry. -

Media Industry Approaches to Comic-To-Live-Action Adaptations and Race

From Serials to Blockbusters: Media Industry Approaches to Comic-to-Live-Action Adaptations and Race by Kathryn M. Frank A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Lisa A. Nakamura Associate Professor Aswin Punathambekar © Kathryn M. Frank 2015 “I don't remember when exactly I read my first comic book, but I do remember exactly how liberated and subversive I felt as a result.” ― Edward W. Said, Palestine For Mom and Dad, who taught me to be my own hero ii Acknowledgements There are so many people without whom this project would never have been possible. First and foremost, my parents, Paul and MaryAnn Frank, who never blinked when I told them I wanted to move half way across the country to read comic books for a living. Their unending support has taken many forms, from late-night pep talks and airport pick-ups to rides to Comic-Con at 3 am and listening to a comics nerd blather on for hours about why Man of Steel was so terrible. I could never hope to repay the patience, love, and trust they have given me throughout the years, but hopefully fewer midnight conversations about my dissertation will be a good start. Amanda Lotz has shown unwavering interest and support for me and for my work since before we were formally advisor and advisee, and her insight, feedback, and attention to detail kept me invested in my own work, even in times when my resolve to continue writing was flagging. -

ABSTRACT the Pdblications of the Marvel Comics Group Warrant Serious Consideration As .A Legitimate Narrative Enterprise

DOCU§ENT RESUME ED 190 980 CS 005 088 AOTHOR Palumbo, Don'ald TITLE The use of, Comics as an Approach to Introducing the Techniques and Terms of Narrative to Novice Readers. PUB DATE Oct 79 NOTE 41p.: Paper' presented at the Annual Meeting of the Popular Culture Association in the South oth, Louisville, KY, October 18-20, 19791. EDFS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage." DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature:,*Comics (Publications) : *Critical Aeading: *English Instruction: Fiction: *Literary Criticism: *Literary Devices: *Narration: Secondary, Educition: Teaching Methods ABSTRACT The pdblications of the Marvel Comics Group warrant serious consIderation as .a legitimate narrative enterprise. While it is obvious. that these comic books can be used in the classroom as a source of reading material, it is tot so obvious that these comic books, with great economy, simplicity, and narrative density, can be used to further introduce novice readers to the techniques found in narrative and to the terms employed in the study and discussion of a narrative. The output of the Marvel Conics Group in particular is literate, is both narratively and pbSlosophically sophisticated, and is ethically and morally responsible. Some of the narrative tecbntques found in the stories, such as the Spider-Man episodes, include foreshadowing, a dramatic fiction narrator, flashback, irony, symbolism, metaphor, Biblical and historical allusions, and mythological allusions.4MKM1 4 4 *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** ) U SOEPANTMENTO, HEALD.. TOUCATiONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE CIF 4 EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT was BEEN N ENO°. DOCEO EXACTLY AS .ReCeIVED FROM Donald Palumbo THE PE aSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGuN- ATING T POINTS VIEW OR OPINIONS Department of English STATED 60 NOT NECESSARILY REPRf SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF O Northern Michigan University EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY CO Marquette, MI.