Identification and Impact of Hyperparasitoids And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Slide Title

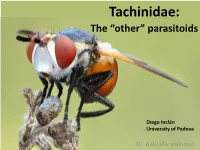

Tachinidae: The “other” parasitoids Diego Inclán University of Padova Outline • Briefly (re-) introduce parasitoids & the parasitoid lifestyle • Quick survey of dipteran parasitoids • Introduce you to tachinid flies • major groups • oviposition strategies • host associations • host range… • Discuss role of tachinids in biological control Parasite vs. parasitoid Parasite Life cycle of a parasitoid Alien (1979) Life cycle of a parasitoid Parasite vs. parasitoid Parasite Parasitoid does not kill the host kill its host Insects life cycles Life cycle of a parasitoid Some facts about parasitoids • Parasitoids are diverse (15-25% of all insect species) • Hosts of parasitoids = virtually all terrestrial insects • Parasitoids are among the dominant natural enemies of phytophagous insects (e.g., crop pests) • Offer model systems for understanding community structure, coevolution & evolutionary diversification Distribution/frequency of parasitoids among insect orders Primary groups of parasitoids Diptera (flies) ca. 20% of parasitoids Hymenoptera (wasps) ca. 70% of parasitoids Described Family Primary hosts Diptera parasitoid sp Sciomyzidae 200? Gastropods: (snails/slugs) Nemestrinidae 300 Orth.: Acrididae Bombyliidae 5000 primarily Hym., Col., Dip. Pipunculidae 1000 Hom.:Auchenorrycha Conopidae 800 Hym:Aculeata Lep., Orth., Hom., Col., Sarcophagidae 1250? Gastropoda + others Lep., Hym., Col., Hem., Tachinidae > 8500 Dip., + many others Pyrgotidae 350 Col:Scarabaeidae Acroceridae 500 Arach.:Aranea Hym., Dip., Col., Lep., Phoridae 400?? Isop.,Diplopoda -

![Ichneumonid Wasps (Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae) in the to Scale Caterpillar (Lepidoptera) [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0863/ichneumonid-wasps-hymenoptera-ichneumonidae-in-the-to-scale-caterpillar-lepidoptera-1-720863.webp)

Ichneumonid Wasps (Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae) in the to Scale Caterpillar (Lepidoptera) [1]

Central JSM Anatomy & Physiology Bringing Excellence in Open Access Research Article *Corresponding author Bui Tuan Viet, Institute of Ecology an Biological Resources, Vietnam Acedemy of Science and Ichneumonid Wasps Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet, Cau Giay, Hanoi, Vietnam, Email: (Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae) Submitted: 11 November 2016 Accepted: 21 February 2017 Published: 23 February 2017 Parasitizee a Pupae of the Rice Copyright © 2017 Viet Insect Pests (Lepidoptera) in OPEN ACCESS Keywords the Hanoi Area • Hymenoptera • Ichneumonidae Bui Tuan Viet* • Lepidoptera Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Vietnam Abstract During the years 1980-1989,The surveys of pupa of the rice insect pests (Lepidoptera) in the rice field crops from the Hanoi area identified showed that 12 species of the rice insect pests, which were separated into three different groups: I- Group (Stem bore) including Scirpophaga incertulas, Chilo suppressalis, Sesamia inferens; II-Group (Leaf-folder) including Parnara guttata, Parnara mathias, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis, Brachmia sp, Naranga aenescens; III-Group (Bite ears) including Mythimna separata, Mythimna loryei, Mythimna venalba, Spodoptera litura . From these organisms, which 15 of parasitoid species were found, those species belonging to 5 families in of the order Hymenoptera (Ichneumonidae, Chalcididae, Eulophidae, Elasmidae, Pteromalidae). Nine of these, in which there were 9 of were ichneumonid wasp species: Xanthopimpla flavolineata, Goryphus basilaris, Xanthopimpla punctata, Itoplectis naranyae, Coccygomimus nipponicus, Coccygomimus aethiops, Phaeogenes sp., Atanyjoppa akonis, Triptognatus sp. We discuss the general biology, habitat preferences, and host association of the knowledge of three of these parasitoids, (Xanthopimpla flavolineata, Phaeogenes sp., and Goryphus basilaris). Including general biology, habitat preferences and host association were indicated and discussed. -

Assemblage of Hymenoptera Arriving at Logs Colonized by Ips Pini (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) and Its Microbial Symbionts in Western Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Ecosystem and Conservation Sciences Faculty Publications Ecosystem and Conservation Sciences 2009 Assemblage of Hymenoptera Arriving at Logs Colonized by Ips pini (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) and its Microbial Symbionts in Western Montana Celia K. Boone Diana Six University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Steven J. Krauth Kenneth F. Raffa Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/decs_pubs Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Boone, Celia K.; Six, Diana; Krauth, Steven J.; and Raffa, Kenneth F., "Assemblage of Hymenoptera Arriving at Logs Colonized by Ips pini (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) and its Microbial Symbionts in Western Montana" (2009). Ecosystem and Conservation Sciences Faculty Publications. 33. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/decs_pubs/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Ecosystem and Conservation Sciences at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ecosystem and Conservation Sciences Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 172 Assemblage of Hymenoptera arriving at logs colonized by Ips pini (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) and its microbial symbionts in western Montana Celia K. Boone Department of Entomology, University of Wisconsin, -

Biological-Control-Programmes-In

Biological Control Programmes in Canada 2001–2012 This page intentionally left blank Biological Control Programmes in Canada 2001–2012 Edited by P.G. Mason1 and D.R. Gillespie2 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; 2Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Agassiz, British Columbia, Canada iii CABI is a trading name of CAB International CABI Head Offi ce CABI Nosworthy Way 38 Chauncey Street Wallingford Suite 1002 Oxfordshire OX10 8DE Boston, MA 02111 UK USA Tel: +44 (0)1491 832111 T: +1 800 552 3083 (toll free) Fax: +44 (0)1491 833508 T: +1 (0)617 395 4051 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cabi.org Chapters 1–4, 6–11, 15–17, 19, 21, 23, 25–28, 30–32, 34–36, 39–42, 44, 46–48, 52–56, 60–61, 64–71 © Crown Copyright 2013. Reproduced with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery. Remaining chapters © CAB International 2013. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electroni- cally, mechanically, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library, London, UK. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Biological control programmes in Canada, 2001-2012 / [edited by] P.G. Mason and D.R. Gillespie. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-78064-257-4 (alk. paper) 1. Insect pests--Biological control--Canada. 2. Weeds--Biological con- trol--Canada. 3. Phytopathogenic microorganisms--Biological control- -Canada. -

The Taxonomy of the Side Species Group of Spilochalcis (Hymenoptera: Chalcididae) in America North of Mexico with Biological Notes on a Representative Species

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1984 The taxonomy of the side species group of Spilochalcis (Hymenoptera: Chalcididae) in America north of Mexico with biological notes on a representative species. Gary James Couch University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Couch, Gary James, "The taxonomy of the side species group of Spilochalcis (Hymenoptera: Chalcididae) in America north of Mexico with biological notes on a representative species." (1984). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 3045. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/3045 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TAXONOMY OF THE SIDE SPECIES GROUP OF SPILOCHALCIS (HYMENOPTERA:CHALCIDIDAE) IN AMERICA NORTH OF MEXICO WITH BIOLOGICAL NOTES ON A REPRESENTATIVE SPECIES. A Thesis Presented By GARY JAMES COUCH Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May 1984 Department of Entomology THE TAXONOMY OF THE SIDE SPECIES GROUP OF SPILOCHALCIS (HYMENOPTERA:CHALCIDIDAE) IN AMERICA NORTH OF MEXICO WITH BIOLOGICAL NOTES ON A REPRESENTATIVE SPECIES. A Thesis Presented By GARY JAMES COUCH Approved as to style and content by: Dr. T/M. Peter's, Chairperson of Committee CJZl- Dr. C-M. Yin, Membe D#. J.S. El kin ton, Member ii Dedication To: My mother who taught me that dreams are only worth the time and effort you devote to attaining them and my father for the values to base them on. -

Diaphorina Citri) in Southern California

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Predators of Asian Citrus Psyllid (Diaphorina citri) in Southern California Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3d61v94f Author Goldmann, Aviva Publication Date 2017 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Predators of Asian Citrus Psyllid (Diaphorina citri) in Southern California A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology by Aviva Goldmann December 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Richard Stouthamer, Chairperson Dr. Matt Daugherty Dr. Jocelyn Millar Dr. Erin Rankin Copyright by Aviva Goldmann 2017 The Dissertation of Aviva Goldmann is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would like to thank my graduate advisor, Dr. Richard Stouthamer, without whom this work would not have been possible. I am more grateful than I can express for his support and for the confidence he placed in my research. I am very grateful to many members of the Stouthamer lab for their help and contributions. Dr. Paul Rugman-Jones gave essential support and guidance during all phases of this project, and contributed substantially to the design and troubleshooting of molecular analyses. The success of the field experiment described in Chapter 2 is entirely due to the efforts of Dr. Anna Soper. Fallon Fowler, Mariana Romo, and Sarah Smith provided excellent field and lab assistance that was instrumental in completing this research. I could not have done it alone, especially at 4:00 AM. -

Parasitoid Gene Expression Changes After Adaptation to Symbiont-Protected Hosts

1 Parasitoid gene expression changes after adaptation to symbiont-protected hosts 2 3 Alice B. Dennis,1,2,3,4 Vilas Patel,5 Kerry M. Oliver,5 and Christoph Vorburger1,2 4 1Institute of Integrative Biology, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland 5 2EAWAG, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland 6 3Current address: Unit of Evolutionary Biology and Systematic Zoology, Institute of Biochemistry and Biology, University 7 of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany 8 4E-mail: [email protected] 9 5Department of Entomology, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602 10 11 Abstract: 12 Reciprocal selection between aphids, their protective endosymbionts, and the parasitoid wasps that 13 prey upon them offers an opportunity to study the basis of their coevolution. We investigated 14 adaptation to symbiont-conferred defense by rearing the parasitoid wasp Lysiphlebus fabarum on 15 aphids (Aphis fabae) possessing different defensive symbiont strains (Hamiltonella defensa). After 16 ten generations of experimental evolution, wasps showed increased abilities to parasitize aphids 17 possessing the H. defensa strain they evolved with, but not aphids possessing the other strain. We 18 show that the two symbiont strains encode different toxins, potentially creating different targets 19 for counter-adaptation. Phenotypic and behavioral comparisons suggest that neither life history 20 traits nor oviposition behavior differed among evolved parasitoid lineages. In contrast, 21 comparative transcriptomics of adult female wasps identified a suite of differentially expressed 22 genes among lineages, even when reared in a common, symbiont-free, aphid host. In concurrence 23 with the specificity of each parasitoid lineages’ infectivity, most differentially expressed parasitoid 24 transcripts were also lineage-specific. -

Surveying for Terrestrial Arthropods (Insects and Relatives) Occurring Within the Kahului Airport Environs, Maui, Hawai‘I: Synthesis Report

Surveying for Terrestrial Arthropods (Insects and Relatives) Occurring within the Kahului Airport Environs, Maui, Hawai‘i: Synthesis Report Prepared by Francis G. Howarth, David J. Preston, and Richard Pyle Honolulu, Hawaii January 2012 Surveying for Terrestrial Arthropods (Insects and Relatives) Occurring within the Kahului Airport Environs, Maui, Hawai‘i: Synthesis Report Francis G. Howarth, David J. Preston, and Richard Pyle Hawaii Biological Survey Bishop Museum Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817 USA Prepared for EKNA Services Inc. 615 Pi‘ikoi Street, Suite 300 Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96814 and State of Hawaii, Department of Transportation, Airports Division Bishop Museum Technical Report 58 Honolulu, Hawaii January 2012 Bishop Museum Press 1525 Bernice Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i Copyright 2012 Bishop Museum All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America ISSN 1085-455X Contribution No. 2012 001 to the Hawaii Biological Survey COVER Adult male Hawaiian long-horned wood-borer, Plagithmysus kahului, on its host plant Chenopodium oahuense. This species is endemic to lowland Maui and was discovered during the arthropod surveys. Photograph by Forest and Kim Starr, Makawao, Maui. Used with permission. Hawaii Biological Report on Monitoring Arthropods within Kahului Airport Environs, Synthesis TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents …………….......................................................……………...........……………..…..….i. Executive Summary …….....................................................…………………...........……………..…..….1 Introduction ..................................................................………………………...........……………..…..….4 -

The Phylogeny and Evolutionary Biology of the Pimplinae (Hymenoptera : Ichneumonidae)

THE PHYLOGENY AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY OF THE PIMPLINAE (HYMENOPTERA : ICHNEUMONIDAE) Paul Eggleton A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London Department of Entomology Department of Pure & Applied B ritish Museum (Natural H istory) Biology, Imperial College London London May 1989 ABSTRACT £ The phylogeny and evolutionary biology of the Pimplinae are investigated using a cladistic compatibility method. Cladistic methodology is reviewed in the introduction, and the advantages of using a compatibility method explained. Unweighted and weighted compatibility techniques are outlined. The presently accepted classification of the Pimplinae is investigated by reference to the diagnostic characters used by earlier workers. The Pimplinae do not form a natural grouping using this character set. An additional 22 new characters are added to the data set for a further analysis. The results show that the Pimplinae (sensu lato) form four separate and unconnected lineages. It is recommended that the lineages each be given subfamily status. Other taxonomic changes at tribal level are suggested. The host and host microhabitat relations of the Pimplinae (sensu s tr ic to ) are placed within the evolutionary framework of the analyses of morphological characters. The importance of a primitive association with hosts in decaying wood is stressed, and the various evolutionary pathways away from this microhabitat discussed. The biology of the Rhyssinae is reviewed, especially with respect to mating behaviour and male reproductive strategies. The Rhyssinae (78 species) are analysed cladistically using 62 characters, but excluding characters thought to be connected with mating behaviour. Morphometric studies show that certain male gastral characters are associated with particular mating systems. -

Spiders in a Hostile World (Arachnoidea, Araneae)

Arachnologische Mitteilungen 40: 55-64 Nuremberg, January 2011 Spiders in a hostile world (Arachnoidea, Araneae) Peter J. van Helsdingen doi: 10.5431/aramit4007 Abstract: Spiders are powerful predators, but the threats confronting them are numerous. A survey is presented of the many different arthropods which waylay spiders in various ways. Some food-specialists among spiders feed exclusively on spiders. Kleptoparasites are found among spiders as well as among Mecoptera, Diptera, Lepidoptera, and Heteroptera. Predators are found within spiders’ own population (cannibalism), among other spider species (araneophagy), and among different species of Heteroptera, Odonata, and Hymenoptera. Parasitoids are found in the orders Hymenoptera and Diptera. The largest insect order, Coleoptera, comprises a few species among the Carabidae which feed on spiders, but beetles are not represented among the kleptoparasites or parasitoids. Key words: aggressive mimicry, araneophagy, cannibalism, kleptoparasitism, parasitoid Spiders are successful predators with important tools for prey capture, ������������������ ������������������������������ viz, venom, diverse types of silk for ������������ ������������������������������ snaring and wrapping, and speed. ����������� ���������������� But spiders are prey for other organ- isms as well. This paper presents a survey of all the threats spiders have to face from other arthropods ������ (excluding mites), based on data from the literature and my own observations. Spiders are often defenceless against the attacks -

Parasitism and Migration in Southern Palaearctic Populations of the Painted Lady Butterfly, Vanessa Cardui (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)

Eur. J. Entomol. 109: 85–94, 2012 http://www.eje.cz/scripts/viewabstract.php?abstract=1683 ISSN 1210-5759 (print), 1802-8829 (online) Parasitism and migration in southern Palaearctic populations of the painted lady butterfly, Vanessa cardui (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) CONSTANTÍ STEFANESCU 1, 2, RICHARD R. ASKEW 3,JORDI CORBERA4 and MARK R. SHAW 5 1 Butterfly Monitoring Scheme, Museu de Granollers-Ciències Naturals, Francesc Macià, 51, Granollers, E-08402, Spain; e-mail: [email protected] 2Global Ecology Unit, CREAF-CEAB-CSIC, Edifici C, Campus de Bellaterra, Bellaterra, E-08193, Spain 3 Beeston Hall Mews, Tarporley, Cheshire, CW6 9TZ, England, UK 4 Secció de Ciències Naturals, Museu de Mataró, El Carreró 17-19, Mataró, E-08301, Spain 5 Honorary Research Associate, National Museums of Scotland, Scotland, UK Key words. Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae, population dynamics, seasonal migration, enemy-free space, primary parasitoids, Cotesia vanessae, secondary parasitoids Abstract. The painted lady butterfly (Vanessa cardui) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Nymphalinae) is well known for its seasonal long-distance migrations and for its dramatic population fluctuations between years. Although parasitism has occasionally been noted as an important mortality factor for this butterfly, no comprehensive study has quantified and compared its parasitoid com- plexes in different geographical areas or seasons. In 2009, a year when this butterfly was extraordinarily abundant in the western Palaearctic, we assessed the spatial and temporal variation in larval parasitism in central Morocco (late winter and autumn) and north-east Spain (spring and late summer). The primary parasitoids in the complexes comprised a few relatively specialized koinobi- onts that are a regular and important mortality factor in the host populations. -

Beiträge Zur Bayerischen Entomofaunistik 13: 67–207

Beiträge zur bayerischen Entomofaunistik 13:67–207, Bamberg (2014), ISSN 1430-015X Grundlegende Untersuchungen zur vielfältigen Insektenfauna im Tiergarten Nürnberg unter besonderer Betonung der Hymenoptera Auswertung von Malaisefallenfängen in den Jahren 1989 und 1990 von Klaus von der Dunk & Manfred Kraus Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung 68 2. Untersuchungsgebiet 68 3. Methodik 69 3.1. Planung 69 3.2. Malaisefallen (MF) im Tiergarten 1989, mit Gelbschalen (GS) und Handfänge 69 3.3. Beschreibung der Fallenstandorte 70 3.4. Malaisefallen, Gelbschalen und Handfänge 1990 71 4. Darstellung der Untersuchungsergebnisse 71 4.1. Die Tabellen 71 4.2. Umfang der Untersuchungen 73 4.3. Grenzen der Interpretation von Fallenfängen 73 5. Untersuchungsergebnisse 74 5.1. Hymenoptera 74 5.1.1. Hymenoptera – Symphyta (Blattwespen) 74 5.1.1.1. Tabelle Symphyta 74 5.1.1.2. Tabellen Leerungstermine der Malaisefallen und Gelbschalen und Blattwespenanzahl 78 5.1.1.3. Symphyta 79 5.1.2. Hymenoptera – Terebrantia 87 5.1.2.1. Tabelle Terebrantia 87 5.1.2.2. Tabelle Ichneumonidae (det. R. Bauer) mit Ergänzungen 91 5.1.2.3. Terebrantia: Evanoidea bis Chalcididae – Ichneumonidae – Braconidae 100 5.1.2.4. Bauer, R.: Ichneumoniden aus den Fängen in Malaisefallen von Dr. M. Kraus im Tiergarten Nürnberg in den Jahren 1989 und 1990 111 5.1.3. Hymenoptera – Apocrita – Aculeata 117 5.1.3.1. Tabellen: Apidae, Formicidae, Chrysididae, Pompilidae, Vespidae, Sphecidae, Mutillidae, Sapygidae, Tiphiidae 117 5.1.3.2. Apidae, Formicidae, Chrysididae, Pompilidae, Vespidae, Sphecidae, Mutillidae, Sapygidae, Tiphiidae 122 5.1.4. Coleoptera 131 5.1.4.1. Tabelle Coleoptera 131 5.1.4.2.