Testing for Pollinator Recognition in Multiple Species of Heliconia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

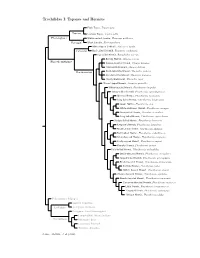

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Nesting Behavior of Reddish Hermits (Phaethornis Ruber) and Occurrence of Wasp Cells in Nests

NESTING BEHAVIOR OF REDDISH HERMITS (PHAETHORNIS RUBER) AND OCCURRENCE OF WASP CELLS IN NESTS YOSHIKA ONIKI REDraSHHermits (Phaethornisruber) are small hummingbirdsof the forested tropical lowlands east of the Andes and south of the Orinoco (Meyer de Schauensee,1966: 161). Five birds mist-nettedat Belem (1 ø 28' S, 48ø 27' W, altitude 13 m) weighed2.0 to 2.5 g (average2.24 g). I studiedtheir nestingfrom 14 October1966 to October1967 at Belem, Brazil, in the Area de PesquisasEco16gicas do Guam•t (APEG) and MocamboForest reserves,in the Instituto de Pesquisase Experimentaqfio Agropecu•triasdo Norte (IPEAN). Names of forest types used and the Portugueseequivalents are: tidal swamp forest (vdrze'a), mature upland forest (terra-/irme) and secondgrowth (capoeira). In all casescapo.eira has been in mature upland situations. At Belem Phaethornisruber is commonall year in the lower levels of secondgrowth (capoeira) where thin branchesare plentiful. Isolated males call frequently from thin horizontal branches,never higher than 2.5-3.0 m. The male sits erect and wags his tail forward and backward as he squeaksa seriesof insectlike"pi-pi-pipipipipipi" notes, 18-20 times per minute; the first two or three notesare short and separated,the rest are run togetherrapidly. The bird sometimesstops calling for someseconds and flasheshis tongue in and out several times during the interval. I foundno singingassemblies of malehermits such as Davis (1934) describes for both the Reddishand Long-tailedHermits (Phaethornissuperciliosus). and Snow (1968) for the Little Hermit (P. longuemareus). Breeding season.--The monthly rainfall at Belem in the year of the study was 350 to 550 mm from January to May and 25 to 200 mm from June to December,with lows in October and November and highs in March and April. -

Observations of Hummingbird Feeding Behavior at Flowers of Heliconia Beckneri and H

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 18: 133–138, 2007 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society OBSERVATIONS OF HUMMINGBIRD FEEDING BEHAVIOR AT FLOWERS OF HELICONIA BECKNERI AND H. TORTUOSA IN SOUTHERN COSTA RICA Joseph Taylor1 & Stewart A. White Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, Graham Kerr Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, CB23 6DH, UK. Observaciones de la conducta de alimentación de colibríes con flores de Heliconia beckneri y H. tortuosa en El Sur de Costa Rica. Key words: Pollination, sympatric, cloud forest, Cloudbridge Nature Reserve, Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy, Violet Sabrewing, Campylopterus hemileucurus, Green-crowned Brilliant, Heliodoxa jacula. INTRODUCTION sources in a single foraging bout (Stiles 1978). Interactions between closely related sympatric The flower preferences shown by humming- flowering plants may involve competition for birds (Trochilidae) are influenced by a com- pollinators, interspecific pollen loss and plex array of factors including their bill hybridization (e.g., Feinsinger 1987). These dimensions, body size, habitat preference and processes drive the divergence of genetically relative dominance, as influenced by age and based floral phenotypes that influence polli- sex, and how these interact with the morpho- nator assemblages and behavior. However, logical, caloric and visual properties of flow- floral convergence may be favored if the ers (e.g., Stiles 1976). increased nectar supplies and flower densities, Hummingbirds are the primary pollina- for example, increase the regularity and rate tors of most Heliconia species (Heliconiaceae) of flower visitation for all species concerned (Linhart 1973), which are medium to large (Schemske 1981). Sympatric hummingbird- clone-forming herbs that usually produce pollinated plants probably face strong selec- brightly colored floral bracts (Stiles 1975). -

The Behavior and Ecology of Hermit Hummingbirds in the Kanaku Mountains, Guyana

THE BEHAVIOR AND ECOLOGY OF HERMIT HUMMINGBIRDS IN THE KANAKU MOUNTAINS, GUYANA. BARBARA K. SNOW OR nearly three months, 17 January to 5 April 1970, my husband and I F camped at the foot of the Kanaku Mountains in southern Guyana. Our camp was situated just inside the forest beside Karusu Creek, a tributary of Moco Moco Creek, at approximately 80 m above sea level. The period of our visit was the end of the main dry season which in this part of Guyana lasts approximately from September or October to April or May. Although we were both mainly occupied with other observations we hoped to accumulate as much information as possible on the hermit hummingbirds of the area, particularly their feeding niches, nesting and social organization. Previously, while living in Trinidad, we had studied various aspects of the behavior and biology of the three hermit hummingbirds resident there: the breeding season (D. W. Snow and B. K. Snow, 1964)) the behavior at singing assemblies of the Little Hermit (Phaethornis Zonguemareus) (D. W. Snow, 1968)) the feeding niches (B. K. Snow and D. W. Snow, 1972)) the social organization of the Hairy Hermit (Glaucis hirsuta) (B. K. Snow, 1973) and its breeding biology (D. W. Snow and B. K. Snow, 1973)) and the be- havior and breeding of the Guys’ Hermit (Phuethornis guy) (B. K. Snow, in press). A total of six hermit hummingbirds were seen in the Karusu Creek study area. Two species, Phuethornis uugusti and Phaethornis longuemureus, were extremely scarce. P. uugusti was seen feeding once, and what was presumably the same individual was trapped shortly afterwards. -

Do Sympatric Heliconias Attract the Same Species of Hummingbird? Observations on the Pollination Ecology of Heliconia Beckneri and H

Do Sympatric Heliconias Attract the Same Species of Hummingbird? Observations on the Pollination Ecology of Heliconia beckneri and H. tortuosa at Cloudbridge Nature Reserve Joseph Taylor University of Glasgow The Hummingbird-Heliconia Project The hummingbird family (Trochilidae), endemic to the Neotropics, is remarkable not only for its beauty but also because of its ability to hover over a flower while feeding, its wing movements a blur. These lively birds require frequent, nutritious feeding to sustain their expenditure of energy, and some plants have evolved to attract and feed them in exchange for pollination services. Prominent among such plants are most species in the genus Heliconia (Heliconiaceae), which are medium to large clone-forming herbs with banana-like leaves (Stiles, 1975). The hummingbird-Heliconia interdependence is a good example of co- evolution, and this study is concerned with one aspect of this relationship. Since several species of hummingbird and Heliconia exist at Cloudbridge, a middle-elevation nature reserve in Costa Rica, we wondered whether particular species of Heliconia had evolved an attraction for particular hummingbird species, which might reduce the chances of hybridisation and pollen loss; or whether the plants compete for a variety of hummingbirds. At Cloudbridge, on the Pacific slope of southern Costa Rica’s Talamanca mountain range, Heliconia beckneri , an endangered species (website 1) restricted to this area and thought to be of hybrid origin (Daniels and Stiles, 1979; website 2), and H. tortuosa occur together. Stiles (1979) names the Green Hermit ( Phaethornis guy ) as the primary pollinator of both species and the Violet Sabrewing ( Campylopterus hemileucurus ) as the secondary pollinator of H. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

Frequency of Arthropods in Stomachs of Tropical Hummingbirds

436 ShortCommunications [Auk, Vol. 103 Frequencyof Arthropods in Stomachsof Tropical Hummingbirds J. v. gEMSEN,JR., • F. GARY STILES,2 AND PETERE. SCOTT1 tMuseumof Zoologyand Department of Zoologyand Physiology, Louisiana State University, BatonRouge, Louisiana 70803 USA, and 2Escuelade Biologfa,Universidad de CostaRica, Ciudad Universitaria "Rodrigo Facio," Costa Rica Although flower nectar is the most conspicuous per we do not record in detail the kinds of arthro- and energeticallyefficient food sourceof humming- pods consumed,except insofar as this may affect the birds,it is notablydeficient in amino acidsand other frequency of detectablearthropod remains. A de- essential nutrients (Baker and Baker 1975, Hains- tailed study of the arthropod diets and foraging tac- worth and Wolf 1976). Therefore, hummingbirds re- ticsof hummingbirdsis in preparation(Hespenheide quire an additional source of proteins, lipids, and and Stiles unpubl. data). other nutrients. In most or all species,these nutrients The specimensreported here were collected (1) are obtainedby consumingsmall arthropods.Yet ar- from 1980 to 1985 by personnel of the Museum of thropod-foragingby hummingbirdsremains very lit- Zoology,Louisiana State University (LSUMZ) or (2) tle studied comparedwith nectar-foraging(Gass and from 1971 to 1985 by Stiles and his students.Ap- Montgomerie1981, Hespenheide and Stilesunpubl. proximately 70% of all specimenswere collectedin data). The few available time-budget studies of for- Bolivia or Peru, 25% in Costa Rica, and the remainder aging hummingbirds(reviewed by Gassand Mont- in northwestern Ecuador, Venezuela, or Darign, Pan- gomerie 1981) indicate that arthropod-hunting con- ama.Twenty recentspecimens of 15 speciesfrom Ec- stitutesonly 2-12%of total foragingtime exceptwhen uador and Peru depositedin the Academyof Natural nectar is scarceor unavailable.An incubating female Sciences,Phildelphia, also were included. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Systematics and Geographic Variation in Long-Tailed Hermit Hummingbirds

ORNITOWGIA NEOTROPICAL 7: 119-148, @ The Neotropical Oroithologi<2! Society SYSTEMATICS ANO GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION IN LONG-TAILEO HERMIT HUMMINGBIROS, THE PHAETHORNIS SUPERCIL/OSUS- MALARIS-LONGIROSTRIS SPECIES GROUP (TROCHILIOAE), WITH NOTES ON THEIR BIOGEOGRAPHY Christoph Hinkelmann* Alexander Koenig Zoological Research Institute and Zoological Museum, Ornithology, Group: Biology and Phylogeny of Tropical Birds, Adenauerallee 160, D-53113 Bonn 1, Germany. Resumen. El grupo de Phaethornis superciliosus y especies relacionadas se compone de tres especies de orígen probablemente monofilético: R superciliosus, R malaris y R longirostris. R longirostris está limitado a América Central y Sudamérica al oeste de los Andes. Existen 6 subespeciesválidas; una de estas, R I. baroni, posiblemente ya ha alcanzado aislamiento reproductivo. Las poblaciones distribuidas entre Guatemala y Costa Rica representan una wna extensa de introgresi6n de caracteres morfol6gicos entre dos subespecies,R I. cephalUsy R I. longirostris. En Sudamérica al este de los Andes, similitudes y introgresi6n de caracteres morfol6gicos indican que 6 subespecies válidas pueden ser asignados a R malaris mientras que R superciliosus incluye dos subespeciesválidas en los dos margenes del Río Amawnas en su curso inferior. En el Perú, caracteres de coloraci6n de R malaris moorei y R m. bolivianUs se mezclan en una zdna de introgresi6n aparentemente en correlaci6n con la distribuci6n altitudinal. Sin embargo, no se puede definir con certeza la posici6n taxon6mica de R malaris ochraceiventris; posiblemente, este taxon ya ha alcanzado el estado de especies.Mientras R tongirostris está completamente aislado geograficámente de R malaris y R superciliosus, las subespeciesde estas dos actuan como paraespecieso alloespecies en varias partes de sus áreas de distribuci6n. -

A Comparison of Hispine Beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Associated with Three Orders of Monocot Host Plants in Lowland Panama

International Journal of Tropical Insect Science Vol. 27, No. 3/4, pp. 159-171, 2008 DOI: 10.1017/S1742758407864071 © icipe 2008 A comparison of hispine beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) associated with three orders of monocot host plants in lowland Panama Christophe Meskens1*, Donald Windsor2 and Thierry Hance1 1 Unite d'Ecologie et de Biogeographie, Biodiversity Research Centre, Universite catholique de Louvain, 4-5, Place Croix du Sud, Louvain-la- Neuve 1348, Belgium: ^Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 0843-03092, Panama (Accepted 17 October 2007) Abstract. The feeding traces in fossil ginger leaves and the conserved phylogenetic relationships seen today in certain clades of hispine beetles on their monocot hosts point towards a long and intimate plant-insect evolutionary relationship. Studies in the 1970s and 1980s documented the rich fauna of rolled-leaf hispine beetles and their association with the Neotropical monocot family Heliconiaceae in Central America. In this report, the taxonomic breadth of these early studies is expanded to include species in the families, Marantaceae, Poaceae, Arecaceae and Costaceae, all with species occurring sympatrically with the Heliconiaceae in lowland Panama. Additionally, the analysis is widened to include open-leaf scraping and internal leaf-mining clades of hispoid Cassidinae. The censuses add more than 5080 Cassidinae herbivore occurrence records on both open and unfurled new leaf rolls of 4600 individual plants. Cluster analysis reveals that while many Hispinae species tend to group with plant species in only one of the three monocot orders, 9 of 16 Hispinae species on Zingiberales hosts were recorded in substantial numbers on both the Heliconiaceae and the Marantaceae, indicating an underlying pattern of feeding flexibility at the host plant family level. -

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies. -

Independent, but Not Synergistic, Effects of Landscape Structure and Climate Drive Pollination of a Tropical Plant, Heliconia Tortuosa

Independent, But Not Synergistic, Effects of Landscape Structure And Climate Drive Pollination of A Tropical Plant, Heliconia Tortuosa Claire E. Dowd ( [email protected] ) Oregon State University Kara G. Leimberger Oregon State University Adam S. Hadley University of Toronto Sarah J.K. Frey Oregon State University Matthew G. Betts Oregon State University Research Article Keywords: climate, landscape structure, habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, pollination, interactive effects Posted Date: April 19th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-322197/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Independent, but not synergistic, effects of landscape structure and climate drive pollination of a tropical plant, Heliconia tortuosa Claire E. Dowd1, Kara G. Leimberger2, Adam S. Hadley2,3, Sarah J. K. Frey2,4, Matthew G. Betts2 Matthew G. Betts [email protected] 1Department of Integrative Biology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA 2Forest Biodiversity Research Network, Department of Forest Ecosystems & Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA 3Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Mississauga, ON, Canada L5L1C6 4College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA Acknowledgements We appreciate the help of our field assistants Michael Atencio, Esteban Sandi, and Mauricio Paniagua. We thank the Las Cruces Biological Station for logistical support. We are grateful to private landowners who allowed us to work on their property. We also thank Ariel Muldoon and Jonathon Valente for their statistical advice. This work was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF-DEB-1050594 and NSF-DEB-1457837 to MGB and ASH) and associated NSF-Research Experience for Undergraduates grant that supported CED.