Supporting Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

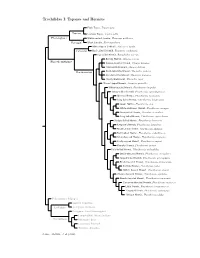

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Ecography ECOG-01538 Maglianesi, M

Ecography ECOG-01538 Maglianesi, M. A., Blüthgen, N., Böhning-Gaese, K. and Schleuning, M. 2015. Topographic microclimates drive microhabitat associations at the range margin of a butterfly. – Ecography doi: 10.1111/ecog.01538 Supplementary material Appendix 1 Table A1. List of families, genera and species of plants recorded by identification of pollen loads carried by hummingbird individuals at three elevations in northeastern Costa Rica. Only plant morphotypes that could be identified to species, genus or family level are given. The proportion of pollen identified to species level was 43% and that identified to a higher taxonomic level was 10%; 47% of pollen grains were categorized into pollen morphotypes (not shown here). Plant families are ordered alphabetically within each elevation. Elevation Family Genus Species Low Bromeliaceae Aechmea Aechmea mariareginae Low Acanthaceae Aphelandra Aphelandra storkii Low Bignoniaceae Arrabidaea Arrabidaea verrucosa Low Gesneraciae Besleria Besleria columnoides Low Alstroemeriaceae Bomarea Bomarea obovata Low Gesneriaceae Columnea Columnea linearis Low Gesneraceae Columnea Columnea nicaraguensis Low Gesneraceae Columnea Columnea purpurata Low Gesneraceae Columnea Columnea querceti Low Costaceae Costus Costus pulverulentus Low Costaceae Costus Costus scaber Low Costaceae Costus Costus sp 1 Low Gesneriaceae Drymonia Drymonia macrophylla Low Ericaceae Ericaceae Ericaceae 1 Low Ericaceae Ericaceae Ericaceae 2 Low Bromeliaceae Guzmania Guzmania monostachia Low Rubiaceae Hamelia Hamelia patens Low Heliconiaceae -

Observations of Hummingbird Feeding Behavior at Flowers of Heliconia Beckneri and H

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 18: 133–138, 2007 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society OBSERVATIONS OF HUMMINGBIRD FEEDING BEHAVIOR AT FLOWERS OF HELICONIA BECKNERI AND H. TORTUOSA IN SOUTHERN COSTA RICA Joseph Taylor1 & Stewart A. White Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, Graham Kerr Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, CB23 6DH, UK. Observaciones de la conducta de alimentación de colibríes con flores de Heliconia beckneri y H. tortuosa en El Sur de Costa Rica. Key words: Pollination, sympatric, cloud forest, Cloudbridge Nature Reserve, Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy, Violet Sabrewing, Campylopterus hemileucurus, Green-crowned Brilliant, Heliodoxa jacula. INTRODUCTION sources in a single foraging bout (Stiles 1978). Interactions between closely related sympatric The flower preferences shown by humming- flowering plants may involve competition for birds (Trochilidae) are influenced by a com- pollinators, interspecific pollen loss and plex array of factors including their bill hybridization (e.g., Feinsinger 1987). These dimensions, body size, habitat preference and processes drive the divergence of genetically relative dominance, as influenced by age and based floral phenotypes that influence polli- sex, and how these interact with the morpho- nator assemblages and behavior. However, logical, caloric and visual properties of flow- floral convergence may be favored if the ers (e.g., Stiles 1976). increased nectar supplies and flower densities, Hummingbirds are the primary pollina- for example, increase the regularity and rate tors of most Heliconia species (Heliconiaceae) of flower visitation for all species concerned (Linhart 1973), which are medium to large (Schemske 1981). Sympatric hummingbird- clone-forming herbs that usually produce pollinated plants probably face strong selec- brightly colored floral bracts (Stiles 1975). -

On the Condors and Humming-Birds of the Equatorial Andes

Annals and Magazine of Natural History Series 4 ISSN: 0374-5481 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tnah10 XXI.—On the condors and humming-birds of the Equatorial Andes James Orton To cite this article: James Orton (1871) XXI.—On the condors and humming-birds of the Equatorial Andes , Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 8:45, 185-192, DOI: 10.1080/00222937108696463 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222937108696463 Published online: 16 Oct 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 3 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tnah10 Download by: [La Trobe University] Date: 15 June 2016, At: 22:45 Mr. J. Ortou on t£e Condors of the Equatorial Andes. 185 [In the 27th cervical vertebra of PleMosaurus Manselii~ Mr. Hulke gives the measurements as :- From front to back of centrum .......... 2~ inches. Width of centrum .................... 4 ,, Depth of centrum .................... 3~ ,, and in the pectoral region the distinctive proportions of width and depth become slightly more marked. The more concave articular face of the eentrum and less thickened peripheral margin of the Kimmeridge species con- firm the specific distinction of the types.] Pectoral vertebra.--The pectoral vertebra of P. wlns2itensis appears to measure-- From front to back of the centrum " 18 inch. Width of centrum .................... 2-) inches. Depth of centrum .................... 1{ inch. Thus the form of the articular surface of the eentrum is broader from side to side than in the neck; it is also a little flatter. -

Project Scientific Progress Report Study Site

Project Ecology of plant-hummingbird interactions along an elevational gradient Scientific Progress Report Project leader: Catherine Graham, Swiss Federal Research Institute Principal investigator: María Alejandra Maglianesi, Universidad Estatal a Distancia Coordinator: Emanuel Brenes Rodríguez, Universidad Estatal a Distancia Study site Las Nubes Biological Reserve York University San José, Costa Rica January, 2020 1 INTRODUCTION A primary aim of community ecology is to identify the processes that govern species assemblages across environmental gradients (McGill et al. 2006), allowing us to understand why biodiversity is non-randomly distributed on Earth. Mutualistic interactions such as those between plants and their animal pollinators are the major biodiversity component from which the integrity of ecosystems depends (Valiente-Banuet et al. 2015). The interdependence of plant and pollinators can be assessed using a network approach, which is a powerful tool to analyze the complexity of ecological systems (Ings et al. 2009), especially in highly diversified tropical regions. Mountain regions provide pronounced environmental gradients across relatively small spatial scales and have proved to be a suitable model system to investigate patterns and determinants of species diversity and community structure (Körner 2000, Sanders and Rahbek 2012). Although some studies have investigated the variation in plant–pollinator interaction networks across elevational gradients (Ramos-Jiliberto et al. 2010, Benadi et al. 2013), such studies are still scarce, particularly in the tropics. In the Neotropics, hummingbirds (Trochilidae) are considered to be effective pollinators (Castellanos et al. 2003). They have been classified into two distinct groups: hermits and non-hermits, which differ mainly in their elevational distribution and their level of specialization on floral resources, i.e., the proportion of floral resources available in the community that is used by species (Stiles 1978). -

The Behavior and Ecology of Hermit Hummingbirds in the Kanaku Mountains, Guyana

THE BEHAVIOR AND ECOLOGY OF HERMIT HUMMINGBIRDS IN THE KANAKU MOUNTAINS, GUYANA. BARBARA K. SNOW OR nearly three months, 17 January to 5 April 1970, my husband and I F camped at the foot of the Kanaku Mountains in southern Guyana. Our camp was situated just inside the forest beside Karusu Creek, a tributary of Moco Moco Creek, at approximately 80 m above sea level. The period of our visit was the end of the main dry season which in this part of Guyana lasts approximately from September or October to April or May. Although we were both mainly occupied with other observations we hoped to accumulate as much information as possible on the hermit hummingbirds of the area, particularly their feeding niches, nesting and social organization. Previously, while living in Trinidad, we had studied various aspects of the behavior and biology of the three hermit hummingbirds resident there: the breeding season (D. W. Snow and B. K. Snow, 1964)) the behavior at singing assemblies of the Little Hermit (Phaethornis Zonguemareus) (D. W. Snow, 1968)) the feeding niches (B. K. Snow and D. W. Snow, 1972)) the social organization of the Hairy Hermit (Glaucis hirsuta) (B. K. Snow, 1973) and its breeding biology (D. W. Snow and B. K. Snow, 1973)) and the be- havior and breeding of the Guys’ Hermit (Phuethornis guy) (B. K. Snow, in press). A total of six hermit hummingbirds were seen in the Karusu Creek study area. Two species, Phuethornis uugusti and Phaethornis longuemureus, were extremely scarce. P. uugusti was seen feeding once, and what was presumably the same individual was trapped shortly afterwards. -

Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2016 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Sophie Wolbert SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Wolbert, Sophie, "Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides" (2016). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2470. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2470 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wolbert 1 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Author: Wolbert, Sophie Academic -

The Best of Costa Rica March 19–31, 2019

THE BEST OF COSTA RICA MARCH 19–31, 2019 Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge © David Ascanio LEADERS: DAVID ASCANIO & MAURICIO CHINCHILLA LIST COMPILED BY: DAVID ASCANIO VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM THE BEST OF COSTA RICA March 19–31, 2019 By David Ascanio Photo album: https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidascanio/albums/72157706650233041 It’s about 02:00 AM in San José, and we are listening to the widespread and ubiquitous Clay-colored Robin singing outside our hotel windows. Yet, it was still too early to experience the real explosion of bird song, which usually happens after dawn. Then, after 05:30 AM, the chorus started when a vocal Great Kiskadee broke the morning silence, followed by the scratchy notes of two Hoffmann´s Woodpeckers, a nesting pair of Inca Doves, the ascending and monotonous song of the Yellow-bellied Elaenia, and the cacophony of an (apparently!) engaged pair of Rufous-naped Wrens. This was indeed a warm welcome to magical Costa Rica! To complement the first morning of birding, two boreal migrants, Baltimore Orioles and a Tennessee Warbler, joined the bird feast just outside the hotel area. Broad-billed Motmot . Photo: D. Ascanio © Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 The Best of Costa Rica, 2019 After breakfast, we drove towards the volcanic ring of Costa Rica. Circling the slope of Poas volcano, we eventually reached the inspiring Bosque de Paz. With its hummingbird feeders and trails transecting a beautiful moss-covered forest, this lodge offered us the opportunity to see one of Costa Rica´s most difficult-to-see Grallaridae, the Scaled Antpitta. -

Do Sympatric Heliconias Attract the Same Species of Hummingbird? Observations on the Pollination Ecology of Heliconia Beckneri and H

Do Sympatric Heliconias Attract the Same Species of Hummingbird? Observations on the Pollination Ecology of Heliconia beckneri and H. tortuosa at Cloudbridge Nature Reserve Joseph Taylor University of Glasgow The Hummingbird-Heliconia Project The hummingbird family (Trochilidae), endemic to the Neotropics, is remarkable not only for its beauty but also because of its ability to hover over a flower while feeding, its wing movements a blur. These lively birds require frequent, nutritious feeding to sustain their expenditure of energy, and some plants have evolved to attract and feed them in exchange for pollination services. Prominent among such plants are most species in the genus Heliconia (Heliconiaceae), which are medium to large clone-forming herbs with banana-like leaves (Stiles, 1975). The hummingbird-Heliconia interdependence is a good example of co- evolution, and this study is concerned with one aspect of this relationship. Since several species of hummingbird and Heliconia exist at Cloudbridge, a middle-elevation nature reserve in Costa Rica, we wondered whether particular species of Heliconia had evolved an attraction for particular hummingbird species, which might reduce the chances of hybridisation and pollen loss; or whether the plants compete for a variety of hummingbirds. At Cloudbridge, on the Pacific slope of southern Costa Rica’s Talamanca mountain range, Heliconia beckneri , an endangered species (website 1) restricted to this area and thought to be of hybrid origin (Daniels and Stiles, 1979; website 2), and H. tortuosa occur together. Stiles (1979) names the Green Hermit ( Phaethornis guy ) as the primary pollinator of both species and the Violet Sabrewing ( Campylopterus hemileucurus ) as the secondary pollinator of H. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

A Comparison of Hispine Beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Associated with Three Orders of Monocot Host Plants in Lowland Panama

International Journal of Tropical Insect Science Vol. 27, No. 3/4, pp. 159-171, 2008 DOI: 10.1017/S1742758407864071 © icipe 2008 A comparison of hispine beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) associated with three orders of monocot host plants in lowland Panama Christophe Meskens1*, Donald Windsor2 and Thierry Hance1 1 Unite d'Ecologie et de Biogeographie, Biodiversity Research Centre, Universite catholique de Louvain, 4-5, Place Croix du Sud, Louvain-la- Neuve 1348, Belgium: ^Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 0843-03092, Panama (Accepted 17 October 2007) Abstract. The feeding traces in fossil ginger leaves and the conserved phylogenetic relationships seen today in certain clades of hispine beetles on their monocot hosts point towards a long and intimate plant-insect evolutionary relationship. Studies in the 1970s and 1980s documented the rich fauna of rolled-leaf hispine beetles and their association with the Neotropical monocot family Heliconiaceae in Central America. In this report, the taxonomic breadth of these early studies is expanded to include species in the families, Marantaceae, Poaceae, Arecaceae and Costaceae, all with species occurring sympatrically with the Heliconiaceae in lowland Panama. Additionally, the analysis is widened to include open-leaf scraping and internal leaf-mining clades of hispoid Cassidinae. The censuses add more than 5080 Cassidinae herbivore occurrence records on both open and unfurled new leaf rolls of 4600 individual plants. Cluster analysis reveals that while many Hispinae species tend to group with plant species in only one of the three monocot orders, 9 of 16 Hispinae species on Zingiberales hosts were recorded in substantial numbers on both the Heliconiaceae and the Marantaceae, indicating an underlying pattern of feeding flexibility at the host plant family level. -

Placement Student's Final Report*

Placement Student’s Final Report* LAURA CANNON *Abridged from original. Contains only Scientific Report portion. SCIENTIFIC REPORT THE EFFECT OF AN ARTIFICAL FEEDER ON HUMMINGBIRD BEHAVIOUR ABSTRACT Like their fellow nectavores, Hummingbirds try to maximize the ratio of energy obtained to energy expended; they try to consume as much nectar with as little movement as they can (Feinsinger, 1978; Hainsworth & Wolf, 1972). The way in which they optimize their consumption is through their ecologically defined roles, they behave in such a way to increase their chances of obtaining food; they often match the length of their bill to the length of the flower. Montgomerie & Gass (1981) noted that Hummingbirds abundance appears to be limited by the availability of nectar. In this study the presence of the artificial feeder provides a constant supply of food while it is up, which could cause a change in the Hummingbirds behaviour for example are maurders (bare in and feed) seen to convert to trapliners (visit multiple flowers), or territorialists (defenders) to become filchers (thieves)? Artificial feeders can affect hummingbirds foraging behaviour and abundance, but despite its potential importance, few previous studies have focused on the consequences of nectar feeders giving contradictory results (Feinsinger, 1978; Sonne et al., 2015). In a study by Arizmendi et al., (2007) the presence of a nectar feeder reduced hummingbird visitation to nearby plants in their study in Mexico. However in Brockmeyer and Schaefer’s study (2012) the number of visits to the flowers around the feeder increased when the feeder was present. This studies main focus is to determine how the presence of an artificial feeder affects the hummingbird’s behaviour specifically feeding, perching and aggression.