Hummingbird Citizen Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

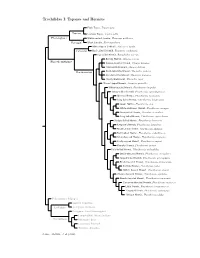

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare-Conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens

Special Publications Museum of Texas Tech University Number xx76 19xx January XXXX 20212010 Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare-conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens Lisa A. Tell, Jenny A. Hazlehurst, Ruta R. Bandivadekar, Jennifer C. Brown, Austin R. Spence, Donald R. Powers, Dalen W. Agnew, Leslie W. Woods, and Andrew Engilis, Jr. Dedications To Sandra Ogletree, who was an exceptional friend and colleague. Her love for family, friends, and birds inspired us all. May her smile and laughter leave a lasting impression of time spent with her and an indelible footprint in our hearts. To my parents, sister, husband, and children. Thank you for all of your love and unconditional support. To my friends and mentors, Drs. Mitchell Bush, Scott Citino, John Pascoe and Bill Lasley. Thank you for your endless encouragement and for always believing in me. ~ Lisa A. Tell Front cover: Photographic images illustrating various aspects of hummingbird research. Images provided courtesy of Don M. Preisler with the exception of the top right image (courtesy of Dr. Lynda Goff). SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS Museum of Texas Tech University Number 76 Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare- conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens Lisa A. Tell, Jenny A. Hazlehurst, Ruta R. Bandivadekar, Jennifer C. Brown, Austin R. Spence, Donald R. Powers, Dalen W. Agnew, Leslie W. Woods, and Andrew Engilis, Jr. Layout and Design: Lisa Bradley Cover Design: Lisa A. Tell and Don M. Preisler Production Editor: Lisa Bradley Copyright 2021, Museum of Texas Tech University This publication is available free of charge in PDF format from the website of the Natural Sciences Research Laboratory, Museum of Texas Tech University (www.depts.ttu.edu/nsrl). -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Observations of Hummingbird Feeding Behavior at Flowers of Heliconia Beckneri and H

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 18: 133–138, 2007 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society OBSERVATIONS OF HUMMINGBIRD FEEDING BEHAVIOR AT FLOWERS OF HELICONIA BECKNERI AND H. TORTUOSA IN SOUTHERN COSTA RICA Joseph Taylor1 & Stewart A. White Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, Graham Kerr Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, CB23 6DH, UK. Observaciones de la conducta de alimentación de colibríes con flores de Heliconia beckneri y H. tortuosa en El Sur de Costa Rica. Key words: Pollination, sympatric, cloud forest, Cloudbridge Nature Reserve, Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy, Violet Sabrewing, Campylopterus hemileucurus, Green-crowned Brilliant, Heliodoxa jacula. INTRODUCTION sources in a single foraging bout (Stiles 1978). Interactions between closely related sympatric The flower preferences shown by humming- flowering plants may involve competition for birds (Trochilidae) are influenced by a com- pollinators, interspecific pollen loss and plex array of factors including their bill hybridization (e.g., Feinsinger 1987). These dimensions, body size, habitat preference and processes drive the divergence of genetically relative dominance, as influenced by age and based floral phenotypes that influence polli- sex, and how these interact with the morpho- nator assemblages and behavior. However, logical, caloric and visual properties of flow- floral convergence may be favored if the ers (e.g., Stiles 1976). increased nectar supplies and flower densities, Hummingbirds are the primary pollina- for example, increase the regularity and rate tors of most Heliconia species (Heliconiaceae) of flower visitation for all species concerned (Linhart 1973), which are medium to large (Schemske 1981). Sympatric hummingbird- clone-forming herbs that usually produce pollinated plants probably face strong selec- brightly colored floral bracts (Stiles 1975). -

The Best of Costa Rica March 19–31, 2019

THE BEST OF COSTA RICA MARCH 19–31, 2019 Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge © David Ascanio LEADERS: DAVID ASCANIO & MAURICIO CHINCHILLA LIST COMPILED BY: DAVID ASCANIO VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM THE BEST OF COSTA RICA March 19–31, 2019 By David Ascanio Photo album: https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidascanio/albums/72157706650233041 It’s about 02:00 AM in San José, and we are listening to the widespread and ubiquitous Clay-colored Robin singing outside our hotel windows. Yet, it was still too early to experience the real explosion of bird song, which usually happens after dawn. Then, after 05:30 AM, the chorus started when a vocal Great Kiskadee broke the morning silence, followed by the scratchy notes of two Hoffmann´s Woodpeckers, a nesting pair of Inca Doves, the ascending and monotonous song of the Yellow-bellied Elaenia, and the cacophony of an (apparently!) engaged pair of Rufous-naped Wrens. This was indeed a warm welcome to magical Costa Rica! To complement the first morning of birding, two boreal migrants, Baltimore Orioles and a Tennessee Warbler, joined the bird feast just outside the hotel area. Broad-billed Motmot . Photo: D. Ascanio © Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 The Best of Costa Rica, 2019 After breakfast, we drove towards the volcanic ring of Costa Rica. Circling the slope of Poas volcano, we eventually reached the inspiring Bosque de Paz. With its hummingbird feeders and trails transecting a beautiful moss-covered forest, this lodge offered us the opportunity to see one of Costa Rica´s most difficult-to-see Grallaridae, the Scaled Antpitta. -

Do Sympatric Heliconias Attract the Same Species of Hummingbird? Observations on the Pollination Ecology of Heliconia Beckneri and H

Do Sympatric Heliconias Attract the Same Species of Hummingbird? Observations on the Pollination Ecology of Heliconia beckneri and H. tortuosa at Cloudbridge Nature Reserve Joseph Taylor University of Glasgow The Hummingbird-Heliconia Project The hummingbird family (Trochilidae), endemic to the Neotropics, is remarkable not only for its beauty but also because of its ability to hover over a flower while feeding, its wing movements a blur. These lively birds require frequent, nutritious feeding to sustain their expenditure of energy, and some plants have evolved to attract and feed them in exchange for pollination services. Prominent among such plants are most species in the genus Heliconia (Heliconiaceae), which are medium to large clone-forming herbs with banana-like leaves (Stiles, 1975). The hummingbird-Heliconia interdependence is a good example of co- evolution, and this study is concerned with one aspect of this relationship. Since several species of hummingbird and Heliconia exist at Cloudbridge, a middle-elevation nature reserve in Costa Rica, we wondered whether particular species of Heliconia had evolved an attraction for particular hummingbird species, which might reduce the chances of hybridisation and pollen loss; or whether the plants compete for a variety of hummingbirds. At Cloudbridge, on the Pacific slope of southern Costa Rica’s Talamanca mountain range, Heliconia beckneri , an endangered species (website 1) restricted to this area and thought to be of hybrid origin (Daniels and Stiles, 1979; website 2), and H. tortuosa occur together. Stiles (1979) names the Green Hermit ( Phaethornis guy ) as the primary pollinator of both species and the Violet Sabrewing ( Campylopterus hemileucurus ) as the secondary pollinator of H. -

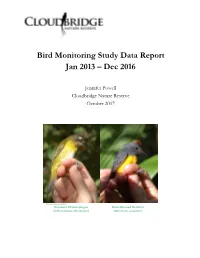

Bird Monitoring Study Data Report Jan 2013 – Dec 2016

Bird Monitoring Study Data Report Jan 2013 – Dec 2016 Jennifer Powell Cloudbridge Nature Reserve October 2017 Photos: Nathan Marcy Common Chlorospingus Slate-throated Redstart (Chlorospingus flavopectus) (Myioborus miniatus) CONTENTS Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Tables .................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Figures................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Project Background ................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Project Goals ................................................................................................................................................... 7 2 Locations ..................................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Current locations ............................................................................................................................................. 8 2.3 Historic locations ..........................................................................................................................................10 -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Campylopterus Ensipennis (White-Tailed Sabrewing)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Campylopterus ensipennis (White-tailed Sabrewing) Family: Trochilidae (Hummingbirds) Order: Trochiliformes (Hummingbirds) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. White-tailed sabrewing, Campylopterus ensipennis. [http://www.flickr.com/photos/findlayfotographics/5977307363/in/photostream/, downloaded 11 November 2012] TRAITS. Hummingbirds are the smallest birds in world yet the white-tailed sabrewing, Campylopterus ensipennis, is one of the largest of the hummingbirds (12 cm) and weighs approximately 10 g (Hilty 2003). This hummingbird is dark green in colour which reflects iridescent specks of light green when the sun falls on its feathers and the wings have blue-black feathers. The male’s throat is navy and royal blue in colour while the female’s is more greyish as males tend to be more brilliant attract the females. They have three pairs of long predominantly white tail feathers (West and Butler 1977). The males tend to be a little larger than the female (West and Butler 1977). They have small feet and prefer to fly than walk. They have a black, long and thin curved bill and tongue which is extendable to enable them to extract nectar when feeding form the flowers (Fig. 1). Their muscular and skeletal form allows them to be adapted UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour for the ability to hover with 10 to 15 wing beats per second and also allow flight in the backward and forward direction (West and Butler 1977; Camfield 2004). ECOLOGY. Campylopterus were mostly found to inhabit around the mountainous areas where the mists and clouds are hovering over the mountains a majority of the time. -

Placement Student's Final Report*

Placement Student’s Final Report* LAURA CANNON *Abridged from original. Contains only Scientific Report portion. SCIENTIFIC REPORT THE EFFECT OF AN ARTIFICAL FEEDER ON HUMMINGBIRD BEHAVIOUR ABSTRACT Like their fellow nectavores, Hummingbirds try to maximize the ratio of energy obtained to energy expended; they try to consume as much nectar with as little movement as they can (Feinsinger, 1978; Hainsworth & Wolf, 1972). The way in which they optimize their consumption is through their ecologically defined roles, they behave in such a way to increase their chances of obtaining food; they often match the length of their bill to the length of the flower. Montgomerie & Gass (1981) noted that Hummingbirds abundance appears to be limited by the availability of nectar. In this study the presence of the artificial feeder provides a constant supply of food while it is up, which could cause a change in the Hummingbirds behaviour for example are maurders (bare in and feed) seen to convert to trapliners (visit multiple flowers), or territorialists (defenders) to become filchers (thieves)? Artificial feeders can affect hummingbirds foraging behaviour and abundance, but despite its potential importance, few previous studies have focused on the consequences of nectar feeders giving contradictory results (Feinsinger, 1978; Sonne et al., 2015). In a study by Arizmendi et al., (2007) the presence of a nectar feeder reduced hummingbird visitation to nearby plants in their study in Mexico. However in Brockmeyer and Schaefer’s study (2012) the number of visits to the flowers around the feeder increased when the feeder was present. This studies main focus is to determine how the presence of an artificial feeder affects the hummingbird’s behaviour specifically feeding, perching and aggression. -

Appendix S1. List of the 719 Bird Species Distributed Within Neotropical Seasonally Dry Forests (NSDF) Considered in This Study

Appendix S1. List of the 719 bird species distributed within Neotropical seasonally dry forests (NSDF) considered in this study. Information about the number of occurrences records and bioclimatic variables set used for model, as well as the values of ROC- Partial test and IUCN category are provide directly for each species in the table. bio 01 bio 02 bio 03 bio 04 bio 05 bio 06 bio 07 bio 08 bio 09 bio 10 bio 11 bio 12 bio 13 bio 14 bio 15 bio 16 bio 17 bio 18 bio 19 Order Family Genera Species name English nameEnglish records (5km) IUCN IUCN category Associated NDF to ROC-Partial values Number Number of presence ACCIPITRIFORMES ACCIPITRIDAE Accipiter (Vieillot, 1816) Accipiter bicolor (Vieillot, 1807) Bicolored Hawk LC 1778 1.40 + 0.02 Accipiter chionogaster (Kaup, 1852) White-breasted Hawk NoData 11 p * Accipiter cooperii (Bonaparte, 1828) Cooper's Hawk LC x 192 1.39 ± 0.06 Accipiter gundlachi Lawrence, 1860 Gundlach's Hawk EN 138 1.14 ± 0.13 Accipiter striatus Vieillot, 1807 Sharp-shinned Hawk LC 1588 1.85 ± 0.05 Accipiter ventralis Sclater, PL, 1866 Plain-breasted Hawk LC 23 1.69 ± 0.00 Busarellus (Lesson, 1843) Busarellus nigricollis (Latham, 1790) Black-collared Hawk LC 1822 1.51 ± 0.03 Buteo (Lacepede, 1799) Buteo brachyurus Vieillot, 1816 Short-tailed Hawk LC 4546 1.48 ± 0.01 Buteo jamaicensis (Gmelin, JF, 1788) Red-tailed Hawk LC 551 1.36 ± 0.05 Buteo nitidus (Latham, 1790) Grey-lined Hawk LC 1516 1.42 ± 0.03 Buteogallus (Lesson, 1830) Buteogallus anthracinus (Deppe, 1830) Common Black Hawk LC x 3224 1.52 ± 0.02 Buteogallus gundlachii (Cabanis, 1855) Cuban Black Hawk NT x 185 1.28 ± 0.10 Buteogallus meridionalis (Latham, 1790) Savanna Hawk LC x 2900 1.45 ± 0.02 Buteogallus urubitinga (Gmelin, 1788) Great Black Hawk LC 2927 1.38 ± 0.02 Chondrohierax (Lesson, 1843) Chondrohierax uncinatus (Temminck, 1822) Hook-billed Kite LC 1746 1.46 ± 0.03 Circus (Lacépède, 1799) Circus buffoni (Gmelin, JF, 1788) Long-winged Harrier LC 1270 1.61 ± 0.03 Elanus (Savigny, 1809) Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 29/09/2021. -

Independent, but Not Synergistic, Effects of Landscape Structure and Climate Drive Pollination of a Tropical Plant, Heliconia Tortuosa

Independent, But Not Synergistic, Effects of Landscape Structure And Climate Drive Pollination of A Tropical Plant, Heliconia Tortuosa Claire E. Dowd ( [email protected] ) Oregon State University Kara G. Leimberger Oregon State University Adam S. Hadley University of Toronto Sarah J.K. Frey Oregon State University Matthew G. Betts Oregon State University Research Article Keywords: climate, landscape structure, habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, pollination, interactive effects Posted Date: April 19th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-322197/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Independent, but not synergistic, effects of landscape structure and climate drive pollination of a tropical plant, Heliconia tortuosa Claire E. Dowd1, Kara G. Leimberger2, Adam S. Hadley2,3, Sarah J. K. Frey2,4, Matthew G. Betts2 Matthew G. Betts [email protected] 1Department of Integrative Biology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA 2Forest Biodiversity Research Network, Department of Forest Ecosystems & Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA 3Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Mississauga, ON, Canada L5L1C6 4College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA Acknowledgements We appreciate the help of our field assistants Michael Atencio, Esteban Sandi, and Mauricio Paniagua. We thank the Las Cruces Biological Station for logistical support. We are grateful to private landowners who allowed us to work on their property. We also thank Ariel Muldoon and Jonathon Valente for their statistical advice. This work was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF-DEB-1050594 and NSF-DEB-1457837 to MGB and ASH) and associated NSF-Research Experience for Undergraduates grant that supported CED.