On the Condors and Humming-Birds of the Equatorial Andes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

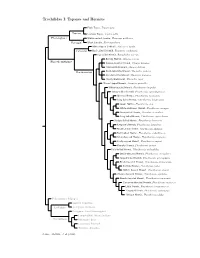

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Ecography ECOG-01538 Maglianesi, M

Ecography ECOG-01538 Maglianesi, M. A., Blüthgen, N., Böhning-Gaese, K. and Schleuning, M. 2015. Topographic microclimates drive microhabitat associations at the range margin of a butterfly. – Ecography doi: 10.1111/ecog.01538 Supplementary material Appendix 1 Table A1. List of families, genera and species of plants recorded by identification of pollen loads carried by hummingbird individuals at three elevations in northeastern Costa Rica. Only plant morphotypes that could be identified to species, genus or family level are given. The proportion of pollen identified to species level was 43% and that identified to a higher taxonomic level was 10%; 47% of pollen grains were categorized into pollen morphotypes (not shown here). Plant families are ordered alphabetically within each elevation. Elevation Family Genus Species Low Bromeliaceae Aechmea Aechmea mariareginae Low Acanthaceae Aphelandra Aphelandra storkii Low Bignoniaceae Arrabidaea Arrabidaea verrucosa Low Gesneraciae Besleria Besleria columnoides Low Alstroemeriaceae Bomarea Bomarea obovata Low Gesneriaceae Columnea Columnea linearis Low Gesneraceae Columnea Columnea nicaraguensis Low Gesneraceae Columnea Columnea purpurata Low Gesneraceae Columnea Columnea querceti Low Costaceae Costus Costus pulverulentus Low Costaceae Costus Costus scaber Low Costaceae Costus Costus sp 1 Low Gesneriaceae Drymonia Drymonia macrophylla Low Ericaceae Ericaceae Ericaceae 1 Low Ericaceae Ericaceae Ericaceae 2 Low Bromeliaceae Guzmania Guzmania monostachia Low Rubiaceae Hamelia Hamelia patens Low Heliconiaceae -

Observations of Hummingbird Feeding Behavior at Flowers of Heliconia Beckneri and H

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 18: 133–138, 2007 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society OBSERVATIONS OF HUMMINGBIRD FEEDING BEHAVIOR AT FLOWERS OF HELICONIA BECKNERI AND H. TORTUOSA IN SOUTHERN COSTA RICA Joseph Taylor1 & Stewart A. White Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, Graham Kerr Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, CB23 6DH, UK. Observaciones de la conducta de alimentación de colibríes con flores de Heliconia beckneri y H. tortuosa en El Sur de Costa Rica. Key words: Pollination, sympatric, cloud forest, Cloudbridge Nature Reserve, Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy, Violet Sabrewing, Campylopterus hemileucurus, Green-crowned Brilliant, Heliodoxa jacula. INTRODUCTION sources in a single foraging bout (Stiles 1978). Interactions between closely related sympatric The flower preferences shown by humming- flowering plants may involve competition for birds (Trochilidae) are influenced by a com- pollinators, interspecific pollen loss and plex array of factors including their bill hybridization (e.g., Feinsinger 1987). These dimensions, body size, habitat preference and processes drive the divergence of genetically relative dominance, as influenced by age and based floral phenotypes that influence polli- sex, and how these interact with the morpho- nator assemblages and behavior. However, logical, caloric and visual properties of flow- floral convergence may be favored if the ers (e.g., Stiles 1976). increased nectar supplies and flower densities, Hummingbirds are the primary pollina- for example, increase the regularity and rate tors of most Heliconia species (Heliconiaceae) of flower visitation for all species concerned (Linhart 1973), which are medium to large (Schemske 1981). Sympatric hummingbird- clone-forming herbs that usually produce pollinated plants probably face strong selec- brightly colored floral bracts (Stiles 1975). -

Project Scientific Progress Report Study Site

Project Ecology of plant-hummingbird interactions along an elevational gradient Scientific Progress Report Project leader: Catherine Graham, Swiss Federal Research Institute Principal investigator: María Alejandra Maglianesi, Universidad Estatal a Distancia Coordinator: Emanuel Brenes Rodríguez, Universidad Estatal a Distancia Study site Las Nubes Biological Reserve York University San José, Costa Rica January, 2020 1 INTRODUCTION A primary aim of community ecology is to identify the processes that govern species assemblages across environmental gradients (McGill et al. 2006), allowing us to understand why biodiversity is non-randomly distributed on Earth. Mutualistic interactions such as those between plants and their animal pollinators are the major biodiversity component from which the integrity of ecosystems depends (Valiente-Banuet et al. 2015). The interdependence of plant and pollinators can be assessed using a network approach, which is a powerful tool to analyze the complexity of ecological systems (Ings et al. 2009), especially in highly diversified tropical regions. Mountain regions provide pronounced environmental gradients across relatively small spatial scales and have proved to be a suitable model system to investigate patterns and determinants of species diversity and community structure (Körner 2000, Sanders and Rahbek 2012). Although some studies have investigated the variation in plant–pollinator interaction networks across elevational gradients (Ramos-Jiliberto et al. 2010, Benadi et al. 2013), such studies are still scarce, particularly in the tropics. In the Neotropics, hummingbirds (Trochilidae) are considered to be effective pollinators (Castellanos et al. 2003). They have been classified into two distinct groups: hermits and non-hermits, which differ mainly in their elevational distribution and their level of specialization on floral resources, i.e., the proportion of floral resources available in the community that is used by species (Stiles 1978). -

The Behavior and Ecology of Hermit Hummingbirds in the Kanaku Mountains, Guyana

THE BEHAVIOR AND ECOLOGY OF HERMIT HUMMINGBIRDS IN THE KANAKU MOUNTAINS, GUYANA. BARBARA K. SNOW OR nearly three months, 17 January to 5 April 1970, my husband and I F camped at the foot of the Kanaku Mountains in southern Guyana. Our camp was situated just inside the forest beside Karusu Creek, a tributary of Moco Moco Creek, at approximately 80 m above sea level. The period of our visit was the end of the main dry season which in this part of Guyana lasts approximately from September or October to April or May. Although we were both mainly occupied with other observations we hoped to accumulate as much information as possible on the hermit hummingbirds of the area, particularly their feeding niches, nesting and social organization. Previously, while living in Trinidad, we had studied various aspects of the behavior and biology of the three hermit hummingbirds resident there: the breeding season (D. W. Snow and B. K. Snow, 1964)) the behavior at singing assemblies of the Little Hermit (Phaethornis Zonguemareus) (D. W. Snow, 1968)) the feeding niches (B. K. Snow and D. W. Snow, 1972)) the social organization of the Hairy Hermit (Glaucis hirsuta) (B. K. Snow, 1973) and its breeding biology (D. W. Snow and B. K. Snow, 1973)) and the be- havior and breeding of the Guys’ Hermit (Phuethornis guy) (B. K. Snow, in press). A total of six hermit hummingbirds were seen in the Karusu Creek study area. Two species, Phuethornis uugusti and Phaethornis longuemureus, were extremely scarce. P. uugusti was seen feeding once, and what was presumably the same individual was trapped shortly afterwards. -

Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2016 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Sophie Wolbert SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Wolbert, Sophie, "Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides" (2016). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2470. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2470 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wolbert 1 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Author: Wolbert, Sophie Academic -

Do Sympatric Heliconias Attract the Same Species of Hummingbird? Observations on the Pollination Ecology of Heliconia Beckneri and H

Do Sympatric Heliconias Attract the Same Species of Hummingbird? Observations on the Pollination Ecology of Heliconia beckneri and H. tortuosa at Cloudbridge Nature Reserve Joseph Taylor University of Glasgow The Hummingbird-Heliconia Project The hummingbird family (Trochilidae), endemic to the Neotropics, is remarkable not only for its beauty but also because of its ability to hover over a flower while feeding, its wing movements a blur. These lively birds require frequent, nutritious feeding to sustain their expenditure of energy, and some plants have evolved to attract and feed them in exchange for pollination services. Prominent among such plants are most species in the genus Heliconia (Heliconiaceae), which are medium to large clone-forming herbs with banana-like leaves (Stiles, 1975). The hummingbird-Heliconia interdependence is a good example of co- evolution, and this study is concerned with one aspect of this relationship. Since several species of hummingbird and Heliconia exist at Cloudbridge, a middle-elevation nature reserve in Costa Rica, we wondered whether particular species of Heliconia had evolved an attraction for particular hummingbird species, which might reduce the chances of hybridisation and pollen loss; or whether the plants compete for a variety of hummingbirds. At Cloudbridge, on the Pacific slope of southern Costa Rica’s Talamanca mountain range, Heliconia beckneri , an endangered species (website 1) restricted to this area and thought to be of hybrid origin (Daniels and Stiles, 1979; website 2), and H. tortuosa occur together. Stiles (1979) names the Green Hermit ( Phaethornis guy ) as the primary pollinator of both species and the Violet Sabrewing ( Campylopterus hemileucurus ) as the secondary pollinator of H. -

Systematics and Geographic Variation in Long-Tailed Hermit Hummingbirds

ORNITOWGIA NEOTROPICAL 7: 119-148, @ The Neotropical Oroithologi<2! Society SYSTEMATICS ANO GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION IN LONG-TAILEO HERMIT HUMMINGBIROS, THE PHAETHORNIS SUPERCIL/OSUS- MALARIS-LONGIROSTRIS SPECIES GROUP (TROCHILIOAE), WITH NOTES ON THEIR BIOGEOGRAPHY Christoph Hinkelmann* Alexander Koenig Zoological Research Institute and Zoological Museum, Ornithology, Group: Biology and Phylogeny of Tropical Birds, Adenauerallee 160, D-53113 Bonn 1, Germany. Resumen. El grupo de Phaethornis superciliosus y especies relacionadas se compone de tres especies de orígen probablemente monofilético: R superciliosus, R malaris y R longirostris. R longirostris está limitado a América Central y Sudamérica al oeste de los Andes. Existen 6 subespeciesválidas; una de estas, R I. baroni, posiblemente ya ha alcanzado aislamiento reproductivo. Las poblaciones distribuidas entre Guatemala y Costa Rica representan una wna extensa de introgresi6n de caracteres morfol6gicos entre dos subespecies,R I. cephalUsy R I. longirostris. En Sudamérica al este de los Andes, similitudes y introgresi6n de caracteres morfol6gicos indican que 6 subespecies válidas pueden ser asignados a R malaris mientras que R superciliosus incluye dos subespeciesválidas en los dos margenes del Río Amawnas en su curso inferior. En el Perú, caracteres de coloraci6n de R malaris moorei y R m. bolivianUs se mezclan en una zdna de introgresi6n aparentemente en correlaci6n con la distribuci6n altitudinal. Sin embargo, no se puede definir con certeza la posici6n taxon6mica de R malaris ochraceiventris; posiblemente, este taxon ya ha alcanzado el estado de especies.Mientras R tongirostris está completamente aislado geograficámente de R malaris y R superciliosus, las subespeciesde estas dos actuan como paraespecieso alloespecies en varias partes de sus áreas de distribuci6n. -

Syllable Sharing and Inter-Individual Syllable Variation in Anna's

Folia Zool. – 56(3): 307–318 (2007) Syllable sharing and inter-individual syllable variation in Anna’s hummingbird Calypte anna songs, in San Francisco, California Xiao-Jing YANG1, 2, 3, Fu-Min LEI1*, Gang WANG4 and Andrea J. JESSE5 1 Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; *e-mail: [email protected] 2 Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; e-mail: [email protected] 3 School of Environmental Studies, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430074, China 4 Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-1800, U.S.A. 5 Department of Ornithology and Mammalogy, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, CA 94118, U.S.A. Received 23 November 2006; Accepted 3 August 2007 A b s t r a c t. We examined the song sharing and variation pattern of 44 Anna’s hummingbird males at syllable level in San Francisco, California. Full songs of Anna’s hummingbird were composed of repeated blocks of phrases. Each male sang from three to six syllable types and syllable repertoire size averaged 5.1. A total of 38 syllable types were identified in songs of the population examined, which can be classified into five basic syllable categories. Each syllable category exhibited different variability among individuals. We quantified the variation of each category and found the variability was highest in the first phrase of song. Using Jaccard’s similarity coefficient, we found the syllable sharing among birds was significantly greater within one sample site than between sites. Using Mantel tests, we demonstrated that syllable sharing among birds tended to decline with the increase of inter-individual geographic distance. -

Glaucis Hirsutus (Rufous-Breasted Hermit)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Glaucis hirsutus (Rufous-breasted Hermit) Family: Trochilidae (Hummingbirds) Order: Trochiliformes (Hummingbirds) Class: Aves Fig. 1. Rufous-breasted hermit, Glaucis hirsutus. [http://www.markprettinaturetours.com/southeast_brazil_photos.htm, downloaded 20 February 2017] TRAITS. Rufous-breasted hermits, also known as hairy hermits, are generally 10-12cm in length, with a bill length of 3-3.5cm, and weigh around 7g. Their bills are curved downwards (Fig. 1) with the upper part being black and the lower having a yellow colour. The head is a darkish-brown with yellowish-beige streaks around their eyes and mouth, and black wings. The feathers at back of their body from head to tail have a bronze green colour and the feathers to the front of their body from their mouth past their belly has a reddish-brown or rufous colour. The tail feathers at the centre have a green colour, with the outer ones being reddish-brown, with black bands above white-tipped ends (Avian Web, 2017; ffrench, 1980). Males and females are almost indistinguishable but males have a streak of yellow in the upper part of their bill and the females have a slightly duller appearance to their feathers as well as a shorter bill that is move curved than the males (Wkikpedia, 2017). UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology DISTRIBUTION. They occur naturally in an arc-like range from Nicaragua in Central America through to the top half of South America to Peru, Bolivia and Brazil, then curves up to Grenada and Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean (Avian Web, 2017). -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Use of Floral Nectar in Heliconia Stilesii Daniels by Three Species of Hermit Hummingbirds

The Condor89~779-787 0 The Cooper OrnithologicalSociety 1987 ECOLOGICAL FITTING: USE OF FLORAL NECTAR IN HELICONIA STILESII DANIELS BY THREE SPECIES OF HERMIT HUMMINGBIRDS FRANK B. GILL The Academyof Natural Sciences,Philadelphia, PA 19103 Abstract. Three speciesof hermit hummingbirds-a specialist(Eutoxeres aquikz), a gen- eralist (Phaethornissuperciliosus), and a thief (Threnetesruckerz]-visited the nectar-rich flowers of Heliconia stilesii Daniels at a lowland study site on the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica. Unlike H. pogonanthaCufodontis, a related Caribbean lowland specieswith a less specialized flower, H. stilesii may not realize its full reproductive potential at this site, becauseit cannot retain the services of alternative pollinators such as Phaethornis.The flowers of H. stilesii appear adapted for pollination by Eutoxeres, but this hummingbird rarely visited them at this site. Lek male Phaethornisvisited the flowers frequently in late May and early June, but then abandonedthis nectar sourcein favor of other flowers offering more accessiblenectar. The strong curvature of the perianth prevents accessby Phaethornis to the main nectar chamber; instead they obtain only small amounts of nectar that leaks anteriorly into the belly of the flower. Key words: Hummingbird; pollination; mutualism;foraging; Heliconia stilesii; nectar. INTRODUCTION Ultimately affectedare the hummingbird’s choice Species that expand their distribution following of flowers and patterns of competition among speciationenter novel ecologicalassociations un- hummingbird species for nectar (Stiles 1975, related to previous evolutionary history and face 1978; Wolf et al. 1976; Feinsinger 1978; Gill the challenges of adjustment to new settings, 1978). Use of specificHeliconia flowers as sources called “ecological fitting” (Janzen 1985a). In the of nectar by particular species of hermit hum- case of mutualistic species, such as plants and mingbirds, however, varies seasonally and geo- their pollinators, new ecological settingsmay in- graphically (Stiles 1975).