Brain Tingles and Scary Holes: Asmr, Trypophobia, and the Sensorial Web

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Wearable Device to Induce and Enhance the ASMR Phenomenon for Mental Well-Being Sub Title Author Jalloul, Safa Ku

Title HESS : a wearable device to induce and enhance the ASMR phenomenon for mental well-being Sub Title Author Jalloul, Safa Kunze, Kai Publisher 慶應義塾大学大学院メディアデザイン研究科 Publication year 2018 Jtitle Abstract Notes 修士学位論文. 2018年度メディアデザイン学 第680号 Genre Thesis or Dissertation URL https://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koara_id=KO40001001-0000201 8-0680 慶應義塾大学学術情報リポジトリ(KOARA)に掲載されているコンテンツの著作権は、それぞれの著作者、学会または出版社/発行者に帰属し、その権利は著作権法によって 保護されています。引用にあたっては、著作権法を遵守してご利用ください。 The copyrights of content available on the KeiO Associated Repository of Academic resources (KOARA) belong to the respective authors, academic societies, or publishers/issuers, and these rights are protected by the Japanese Copyright Act. When quoting the content, please follow the Japanese copyright act. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Master's Thesis Academic Year 2018 HESS: a Wearable Device to Induce and Enhance the ASMR Phenomenon for Mental Well-being Keio University Graduate School of Media Design Safa Jalloul A Master's Thesis submitted to Keio University Graduate School of Media Design in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Media Design Safa Jalloul Master's Thesis Advisory Committee: Associate Professor Kai Kunze (Main Research Supervisor) Professor Matthew Waldman (Sub Research Supervisor) Master's Thesis Review Committee: Associate Professor Kai Kunze (Chair) Professor Matthew Waldman (Co-Reviewer) Professor Keiko Okawa (Co-Reviewer) Abstract of Master's Thesis of Academic Year 2018 HESS: a Wearable Device to Induce and Enhance the ASMR Phenomenon for Mental Well-being Category: Design Summary In our fast-paced society, stress and anxiety have become increasingly common. The ability to find coping mechanisms becomes essential to reach a healthy mental condition. -

Post-Postmodernisms, Hauntology and Creepypasta Narratives As Digital

Spectres des monstres: Post-postmodernisms, hauntology and creepypasta narratives as digital fiction ONDRAK, Joe Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/23603/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version ONDRAK, Joe (2018). Spectres des monstres: Post-postmodernisms, hauntology and creepypasta narratives as digital fiction. Horror Studies, 9 (2), 161-178. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Spectres des Monstres: Post-postmodernisms, hauntology and creepypasta narratives as digital fiction Joe Ondrak, Sheffield Hallam University Abstract Horror has always been adaptable to developments in media and technology; this is clear in horror tales from Gothic epistolary novels to the ‘found footage’ explosion of the early 2000s via phantasmagoria and chilling radio broadcasts such as Orson Welles’ infamous War of the Worlds (1938). It is no surprise, then, that the firm establishment of the digital age (i.e. the widespread use of Web2.0 spaces the proliferation of social media and its integration into everyday life) has created venues not just for interpersonal communication, shared interests and networking but also the potential for these venues to host a new type of horror fiction: creepypasta. However, much of the current academic attention enjoyed by digital horror fiction and creepypasta has focused on digital media’s ability to remediate a ‘folk-like’ storytelling style and an emulation of word-of-mouth communication primarily associated with urban legends and folk tales. -

Transactional Tingles and Asmr As Emerging Media Genre

Selected Papers of #AoIR2020: The 21st Annual Conference of the Association of Internet Researchers Virtual Event / 27-31 October 2020 “EXACTLY WHAT I NEEDED FOR A GOOD NIGHT’S REST”: TRANSACTIONAL TINGLES AND ASMR AS EMERGING MEDIA GENRE Jessica Maddox, Ph.D Department of Journalism and Creative Media, The University of Alabama Abstract A young, brunette woman sits in a polished, modern bedroom. She wears thick, noise- cancelling headphones and sits behind a binaural microphone. She flutters her fingers next to the mic and begins to speak in a voice only a hair above a whisper. “Tonight,” she says, “I’m going to be humming you to sleep” (Gibi ASMR, 2019). The video, simply titled “ASMR | Humming You to Sleep,” has over one million views. Its creator, the whispering brunette in noise-cancelling headphones, is Gibi ASMR, a YouTube creator who has 2.48 million subscribers and is largely considered among the YouTube ASMR community to be one of its greatest “ASMRtists.” ASMR, or Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response, has become an international phenomenon in recent years, with YouTube creators hailing from around the globe. Additionally, the phenomenon gained cultural prominence when it was featured during a Michelob Ultra beer commercial during the 2019 American National Football League Superbowl, as well as in a feature- length film produced by Reese’s Canada that combined five prominent ASMRtists, whispering, and candy. But what exactly ASMR is remains fraught with misunderstandings and cultural slippages. ASMR itself is a relatively new term, coined by scientists in 2010, but it describes an age-old biological feeling: the sensation of tingling on the scalp and down the spine. -

A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Investigation of the Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response

A functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation of the autonomous sensory meridian response Stephen D. Smith1, Beverley K. Fredborg2 and Jennifer Kornelsen3 1 Department of Psychology, University of Winnipeg, Winnipeg, MB, Canada 2 Department of Psychology, Ryerson University, Toronto, ON, Canada 3 Department of Radiology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada ABSTRACT Background: Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR) is a sensory-emotional experience in which specific stimuli (ASMR “triggers”) elicit tingling sensations on the scalp, neck, and shoulders; these sensations are accompanied by a positive affective state. In the current research, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was used in order to delineate the neural substrates of these responses. Methods: A total of 17 individuals with ASMR and 17 age- and sex-matched control participants underwent fMRI scanning while watching six 4-minute videos. Three of the videos were designed to elicit ASMR tingling and three videos were not. Results: The results demonstrated that ASMR videos have a distinct effect on the neural activity of individuals with ASMR. The contrast of ASMR participants’ responses to ASMR videos showed greater activity in the cingulate gyrus as well as in cortical regions related to audition, movement, and vision. This activity was not observed in control participants. The contrast of ASMR and control participants’ responses to ASMR-eliciting videos detected greater activity in right cingulate gyrus, right paracentral lobule, and bilateral thalamus in ASMR participants; control participants showed greater activity in the lingula and culmen of the cerebellum. Conclusions: Together, these results highlight the fact that ASMR videos elicit Submitted 11 January 2019 activity in brain areas related to sensation, emotion, and attention in individuals with Accepted 14 May 2019 Published 21 June 2019 ASMR, but not in matched control participants. -

Daniela Beckelhymer, Emily Thompson, and Carin Perilloux Southwestern University

Who Feels the Tingles? The Emotional Side of ASMR Daniela Beckelhymer, Emily Thompson, and Carin Perilloux Southwestern University Introduction Results • ASMR is a radiating sensation involving tingling or goosebumps that produces a calming or euphoric feeling, Backward regressions predicting ASMR-15 scores Self-perceived social support usually in response to audiovisual stimuli (such as repetitive As anticipated, several predictors were associated with sounds, soothing visuals, and simulated personal attention). Self-perceived social support was positively correlated with higher scores on ASMR subscales: three of the ASMR subscales: • Although there is very little empirical research on ASMR, what physical secure Altered Consciousness r(18278) = .01, p = .19, n.s. empathy we know so far is that people who consume ASMR content sensitivity attachment tend to score higher on empathy, mindfulness, awareness, Sensation r(18278) = .07, p < .001*** dismissive difficulty Relaxation r(18278) = .09, p < .001*** curiosity, openness, and fantasizing (Fredborg, Clark & Smith, femininity attachment describing feelings 2017; 2018; McErlean & Banissey, 2017). Affect r(18278) = .07, p < .001*** • In our study, we collected data from a very large, worldwide sample of ASMR users to replicate some of these effects but but negatively correlated with actual ASMR consumption: Surprisingly, vividness was a consistent predictor of also to test which predictors of ASMR experience would be Days per week r(17922) = -.04, p < .001*** strongest. lower scores on all ASMR subscales. Time per sitting r(18250) = -.04, p < .001*** Method • We recruited participants (N = 26,930) through online Affect Relaxation Sensation Altered consiousness ASMR communities and social media, including ASMR YouTube channel posts. Discussion • Ages 18 to 99 (M = 26.39, SD = 8.32) Vividness • Our regression analyses demonstrated quite a bit of similarity Women 20,442 Neuroticism and consistency predicting the four facets of ASMR. -

Evolution of the Youtube Personas Related to Survival Horror Games

Toniolo EVOLUTION OF THE YOUTUBE PERSONAS RELATED TO SURVIVAL HORROR GAMES FRANCESCO TONIOLO CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF MILAN ABSTRACT The indie survival horror game genre has given rise to some of the most famous game streamers on YouTube, especially titles likes Amnesia: The Dark Descent (Frictional Games 2010), Slender: The Eight Pages (Parsec Productions 2012), and Five Nights at Freddy’s (Scott Cawthon 2014). The games are strongly focused on horror tropes including jump scares and defenceless protagonists, which lend them to displays of overemphasised emotional reactions by YouTubers, who use them to build their online personas in a certain way. This paper retraces the evolution of the relationship between horror games and YouTube personas, with attention to in-game characters and gameplay mechanics on the one hand and the practices of prominent YouTube personas on the other. It will show how the horror game genre and related media, including “Let’s play” videos, animated fanvids, and “creepypasta” stories have influenced prominent YouTuber personas and resulted in some changes in the common processes of persona formation on the platform. KEY WORDS Survival Horror; Video Game; YouTube; Creepypasta; Fanvid; Let’s Play INTRODUCTION Marshall & Barbour (2015, p. 7) argue that “Game culture consciously moves the individual into a zone of production and constitution of public identity”. Similarly, scholars have studied – with different foci and levels of analysis – the relationships between gamers and avatars in digital worlds or in tabletop games by using the concept of “persona” (McMahan 2003; Waskul & Lust 2004; Isbister 2006; Frank 2012). Often, these scholars were concerned with online video games such as World of Warcraft (Filiciak 2003; Milik 2017) or famous video game icons like Lara Croft from the Tomb Raider series (McMahan 2008). -

Art Streaming on the Videogame Platform Twitch

Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences | 2020 Laboring Artists: Art Streaming on the Videogame Platform Twitch Andrew M. Phelps Mia Consalvo University of Canterbury, HITLabNZ (and) Concordia University American University, School of Communication Department of Communication Studies Christchurch, NZ, and Washington, DC, USA Montreal, Canada [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Twitch and YouTube, which push an increasing conformity for laboring individuals that is spilling The relationship between labor and play is over into other types of (non-gaming) streaming complex and multifaceted, particularly so as it relates activities. To justify this assertion, this paper does two to the playing of games. With the rise of the online things: it revisits and highlights key findings from past streaming of games and play these platforms and game studies research that has examined game related activities have expanded the associated practices in labor practices and suggests how platforms played a ways that are highly nuanced and dictated in part by role in shaping labor practices; and via a case study of the platform itself. This paper explores the question art/game streamers it demonstrates how individuals as to whether the types of labor practices found in engage in play, community building, art creation and games hold across other non-game activities as they self-promotion of their work via sites such as Twitch engage with streaming through an observational study which provide a new layer of “authenticity” to their of art streamers on Twitch. By examining art labor, with numerous parallels to the myriad of ways streamers and comparing their labor to that of games games and labor are interwoven. -

Creepypasta – the Modern Twist in Horror Literature

„Kwartalnik Opolski” 2016, 4 Przemysław SIEK Creepypasta – the modern twist in horror literature The 21st century saw humanity making great advancements in many fields, such as medicine or science, none however has had as great an impact as the rise of the Internet. Ever since it was open to the general public, there have been many debates as to whether it is a useful tool which gives us endless possibilities, or perhaps a means of turning people into mindless, antisocial zombies. Although one could find arguments to justify both of these claims, it is true that as technology is developing, people appear to be less inclined to read. This is demonstrated in a study conducted by Jessica E. Moyer entitled “Teens Today Don’t Read Books Anymore”1 among many others. If this is the case, can we say that using the Internet leads to illiteracy and portends the fall of literature? Not quite. As we all know, everything depends on how we use the tools we are given – and such is the case here. A truly remarkable example of how the Internet can lead to popularizing both reading and writing, and even contribute to literature itself appeared several years ago. It is known as Creepypasta and has unfortunately been rarely discussed in the media (only a few articles have been published so far), and almost completely ignored by literary scholars. In the past, literature was passed down orally – this is mirrored by how Creepypastas circulate. The only difference is that the voice of a story- teller has been replaced by electronic communication devices. -

Of Internet Born: Idolatry, the Slender Man Meme, and the Feminization of Digital Spaces

Feminist Media Studies ISSN: 1468-0777 (Print) 1471-5902 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfms20 Of Internet born: idolatry, the Slender Man meme, and the feminization of digital spaces Jessica Maddox To cite this article: Jessica Maddox (2018) Of Internet born: idolatry, the Slender Man meme, and the feminization of digital spaces, Feminist Media Studies, 18:2, 235-248, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2017.1300179 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1300179 Published online: 15 Mar 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 556 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfms20 FEMINIST MEDIA STUDIES, 2018 VOL. 18, NO. 2, 235–248 https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1300179 Of Internet born: idolatry, the Slender Man meme, and the feminization of digital spaces Jessica Maddox Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, The University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This paper examines 96 US and British Commonwealth articles on the Received 31 May 2016 2014 Wisconsin Slender Man stabbing. Using critical textual analysis, Revised 28 October 2016 this study examined how media took a horror-themed meme from Accepted 29 January 2017 the underbelly of the Internet and curated a moral panic, once the KEYWORDS meme was thrust into the international limelight. Because memes are Memes; Internet; idolatry; a particular intersection of images and technology, media made sense Slender Man; technology; of this meme-inspired attack in three ways: (1) through an idolatrous feminism tone that played on long-standing Western anxieties over images; (2) by hyper-sensationalizing women’s so-called frivolous uses of technology; and (3) by removing blame from the assailants and, in turn, finding the Internet and the Slender Man meme guilty in the court of public opinion. -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution

Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Fear Has No Face: Creepypasta as Digital Legendry Trevor J. Blank and Lynne S. McNeill 3 1 “The Sort of Story That Has You Covering Your Mirrors”: The Case of Slender Man Jeffrey A. Tolbert 25 2 The Cowl of Cthulhu: Ostensive Practice in the Digital Age Andrew Peck 51 3 “What Happens When the Pictures Are No Longer Photoshops?” Slender Man, Belief, and the Unacknowledged Common Experience Andrea Kitta 77 4 “Dark and Wicked Things”: Slender Man, the Folkloresque, and the Implications of Belief Jeffrey A. Tolbert 91 5 The Emperor’s New Lore; or, Who Believes in the Big Bad Slender Man? Mikel J. Koven 113 6 Slender COPYRIGHTEDMan, H. P. Lovecraft, and the MATERIALDynamics of Horror Cultures NOTTimothy FOR H. EvansDISTRIBUTION 128 7 Slender Man Is Coming to Get Your Little Brother or Sister: Teenagers’ Pranks Posted on YouTube Elizabeth Tucker 141 8 Monstrous Media and Media Monsters: From Cottingley to Waukesha Paul Manning 155 Notes on the Authors 183 Index 185 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION Figure 0.1. Original caption: “One of two recovered photographs from the Stirling City Library blaze. Notable for being taken the day which fourteen chil- dren vanished and for what is referred to as ‘The Slender Man’. Deformities cited as film defects by officials. Fire at library occurred one week later. Actual photograph confiscated as evidence.—1986, photographer: Mary Thomas, missing since June 13th, 1986.” (http://knowyourmeme.com/memes /slender-man.) Introduction Fear Has No Face Creepypasta as Digital Legendry Trevor J. Blank and Lynne S. -

What Makes the Foundation Seem So Realistic? How Is T

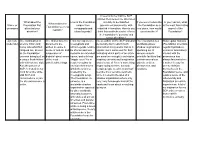

It seems to me that the SCP articles themselves are structured What about the How is the Foundation similarly to declassified If you were to describe In your opinion, what What makes the Name or Foundation first unique from government documents, with the Foundation as a is the most fascinating Foundation seem so username attracted your creepypasta and redacted information. How do you real place, how would aspect of the realistic? attention? urban legends? think this aesthetic choice effects you describe it? Foundation? the Foundation's 'persona' and sense of realism? Zyn (site The combination of The clinical tone the From my experience, I'm an author on the SCP wiki and I The Foundation is a How regular humans moderator) science fiction and documents are creepypasta and personally don't redact much worldwide-power (Foundation scientists, horror was what first written in evoke a urban legends tend to information in my works, but as a shadow organization regular bystanders, intrigued me, as well sense of realism and be shorter and less stylistic tool it works well for both operating out of victims of anomalies) as the Foundation suspension of rooted in an extended indicating which parts of an article various esoteric interact with the universe being built on disbelief about some canon, and with less are sensitive enough to be hidden, scientific facilities that anomalous has a unique flash-fiction- of the most "wiggle room" for a inspiring curiosity and imagination contain anomalous always fascinated me. with-clinical-tone style. unbelievable things. reader or author to and a sense of "there's something objects, entities, It makes it easy for Also the picture of envision themselves bigger going on here, but only phenomena, and one to envision SCP-173 stuck in my within the universe certain people need to know that". -

Increased Misophonia in Self-Reported Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Goldsmiths Research Online Increased misophonia in self-reported Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response Agnieszka B. Janik McErlean1,2 and Michael J. Banissy1 1 Goldsmiths, University of London, London, United Kingdom 2 Bath Spa University, Bath, United Kingdom ABSTRACT Background. Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR) is a sensory experi- ence elicited by auditory and visual triggers, which so far received little attention from the scientific community. This self-reported phenomenon is described as a relaxing tingling sensation, which typically originates on scalp and spreads through a person's body. Recently it has been suggested that ASMR shares common characteristics with another underreported condition known as misophonia, where sounds trigger negative physiological, emotional and behavioural responses. The purpose of this study was to elucidate whether ASMR is associated with heightened levels of misophonia. Methods. The Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) was administered to individuals reporting to experience ASMR and to age and gender matched controls. Results. Compared to controls ASMR group scored higher on all subscales of MQ including the Misophonia Symptom Scale, the Misophonia Emotions and Behaviors Scale and the Misophonia Severity Scale. Discussion. Individuals reporting ASMR experience have elevated levels of misophonia. Subjects Psychiatry and Psychology Keywords ASMR, Misophonia, Synaesthesia, Sensation, Sound INTRODUCTION Submitted 8 March 2018 Accepted 10 July 2018 Sensitivity to sound, especially sound produced by humans, is termed misophonia, which Published 6 August 2018 literally means `hatred of sound' (Jastreboff & Jastreboff, 2002). Although misophonia is not Corresponding author formally recognized as a disorder, recent evidence suggests that clinical symptomatology Agnieszka B.