A Comparison of the Dinosaur Communities from the Middle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cephalobus Litoralis: Biology and Tolerance to Desiccation

Journal of Nematology 20(2):327-329. 1988. © The Society of Nematologists 1988. Cephalobus litorali . Biology and Tolerance to Desiccation M. SAEED, S. A. KHAN, V. A. SAEED, AND H. A. KHAN1 Abstract: Cephalobus litoralis (Akhtar, 1962) Andr~ssy, 1984 reproduced parthenogenetically and completed its life cycle in 72-90 hours. Each female deposited 200-300 eggs. The nematodes showed synchronized movements in the rhythms of the anterior parts of the body. The nematodes were coiled when dried in culture medium or in slowly evaporating water droplets on the tops of culture plates, but in pellets they assumed irregular postures. Nematodes in pellets stored at high humidity could be reactivated after storage for 28 days. Key words: behavior, Cephalobus litoralis, coiling, desiccation tolerance, life cycle, parthenogenesis, synchronized movement. Cephalobus litoralis (Akhtar) Andrfissy, by a modified Baermann funnel method. 1984 was described in 1962 by Akhtar (1) A single gravid female was placed in a cav- as Paracephalobus litoralis based on only two ity slide containing water. After oviposi- female specimens collected from soil tion, a single egg was transferred to a petri around the roots of sugarcane (Saccharum dish containing finely blended pea meal o~cinarum L.) in the agricultural farms of paste (PMP) and water. All experiments the Pakistan Council of Scientific and In- were conducted with nematodes from sin- dustrial Research (PCSIR), Lahore, Paki- gle egg progeny raised in this manner. stan. It had not been reported elsewhere For mass rearing, nematodes were cul- until the authors found it in Karachi. In tured in 14-cm-d petri dishes containing 1967 Andrfissy (3) transferred Eucephalo- pea meal paste. -

Modelling Panspermia in the TRAPPIST-1 System

October 13, 2017 Modelling panspermia in the TRAPPIST-1 system James A. Blake1,2*, David J. Armstrong1,2, Dimitri Veras1,2 Abstract The recent ground-breaking discovery of seven temperate planets within the TRAPPIST-1 system has been hailed as a milestone in the development of exoplanetary science. Centred on an ultra-cool dwarf star, the planets all orbit within a sixth of the distance from Mercury to the Sun. This remarkably compact nature makes the system an ideal testbed for the modelling of rapid lithopanspermia, the idea that micro-organisms can be distributed throughout the Universe via fragments of rock ejected during a meteoric impact event. We perform N-body simulations to investigate the timescale and success-rate of lithopanspermia within TRAPPIST-1. In each simulation, test particles are ejected from one of the three planets thought to lie within the so-called ‘habitable zone’ of the star into a range of allowed orbits, constrained by the ejection velocity and coplanarity of the case in question. The irradiance received by the test particles is tracked throughout the simulation, allowing the overall radiant exposure to be calculated for each one at the close of its journey. A simultaneous in-depth review of space microbiological literature has enabled inferences to be made regarding the potential survivability of lithopanspermia in compact exoplanetary systems. 1Department of Physics, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL 2Centre for Exoplanets and Habitability, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL *Corresponding author: [email protected] Contents Universe, and can propagate from one location to another. This interpretation owes itself predominantly to the works of William 1 Introduction1 Thompson (Lord Kelvin) and Hermann von Helmholtz in the 1.1 Mechanisms for panspermia...............2 latter half of the 19th Century. -

Triassic- Jurassic Stratigraphy Of

Triassic- Jurassic Stratigraphy of the <JF C7 JL / Culpfeper and B arbour sville Basins, VirginiaC7 and Maryland/ ll.S. PAPER Triassic-Jurassic Stratigraphy of the Culpeper and Barboursville Basins, Virginia and Maryland By K.Y. LEE and AJ. FROELICH U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1472 A clarification of the Triassic--Jurassic stratigraphic sequences, sedimentation, and depositional environments UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1989 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MANUEL LUJAN, Jr., Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Lee, K.Y. Triassic-Jurassic stratigraphy of the Culpeper and Barboursville basins, Virginia and Maryland. (U.S. Geological Survey professional paper ; 1472) Bibliography: p. Supt. of Docs. no. : I 19.16:1472 1. Geology, Stratigraphic Triassic. 2. Geology, Stratigraphic Jurassic. 3. Geology Culpeper Basin (Va. and Md.) 4. Geology Virginia Barboursville Basin. I. Froelich, A.J. (Albert Joseph), 1929- II. Title. III. Series. QE676.L44 1989 551.7'62'09755 87-600318 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section, U.S. Geological Survey, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.......................................................................................................... 1 Stratigraphy Continued Introduction... .......................................................................................... -

Lower Jurassic to Lower Middle Jurassic Succession at Kopy Sołtysie and Płaczliwa Skała in the Eastern Tatra Mts (Western

Volumina Jurassica, 2013, Xi: 19–58 Lower Jurassic to lower Middle Jurassic succession at Kopy Sołtysie and Płaczliwa Skała in the eastern Tatra Mts (Western Carpathians) of Poland and Slovakia: stratigraphy, facies and ammonites Jolanta IWAŃCZUK1, Andrzej IWANOW1, Andrzej WIERZBOWSKI1 Key words: stratigraphy, Lower to Middle Jurassic, ammonites, microfacies, correlations, Tatra Mts, Western Carpathians. Abstract. The Lower Jurassic and the lower part of the Middle Jurassic deposits corresponding to the Sołtysia Marlstone Formation of the Lower Subtatric (Krížna) nappe in the Kopy Sołtysie mountain range of the High Tatra Mts and the Płaczliwa Skała (= Ždziarska Vidla) mountain of the Belianske Tatra Mts in the eastern part of the Tatra Mts in Poland and Slovakia are described. The work concentrates both on their lithological and facies development as well as their ammonite faunal content and their chronostratigraphy. These are basinal de- posits which show the dominant facies of the fleckenkalk-fleckenmergel type and reveal the succession of several palaeontological microfacies types from the spiculite microfacies (Sinemurian–Lower Pliensbachian, but locally also in the Bajocian), up to the radiolarian microfacies (Upper Pliensbachian and Toarcian, Bajocian–Bathonian), and locally the Bositra (filament) microfacies (Bajocian– Bathonian). In addition, there appear intercalations of detrital deposits – both bioclastic limestones and breccias – formed by downslope transport from elevated areas (junction of the Sinemurian and Pliensbachian, Upper Toarcian, and Bajocian). The uppermost Toarcian – lowermost Bajocian interval is represented by marly-shaly deposits with a marked admixture of siliciclastic material. The deposits are correlated with the coeval deposits of the Lower Subtatric nappe of the western part of the Tatra Mts (the Bobrowiec unit), as well as with the autochthonous-parachthonous Hightatric units, but also with those of the Czorsztyn and Niedzica successions of the Pieniny Klippen Belt, in Poland. -

Appendix 3.Pdf

A Geoconservation perspective on the trace fossil record associated with the end – Ordovician mass extinction and glaciation in the Welsh Basin Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Nicholls, Keith H. Citation Nicholls, K. (2019). A Geoconservation perspective on the trace fossil record associated with the end – Ordovician mass extinction and glaciation in the Welsh Basin. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Publisher University of Chester Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 26/09/2021 02:37:15 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/622234 International Chronostratigraphic Chart v2013/01 Erathem / Era System / Period Quaternary Neogene C e n o z o i c Paleogene Cretaceous M e s o z o i c Jurassic M e s o z o i c Jurassic Triassic Permian Carboniferous P a l Devonian e o z o i c P a l Devonian e o z o i c Silurian Ordovician s a n u a F y r Cambrian a n o i t u l o v E s ' i k s w o Ichnogeneric Diversity k p e 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 S 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 n 23 r e 25 d 27 o 29 M 31 33 35 37 39 T 41 43 i 45 47 m 49 e 51 53 55 57 59 61 63 65 67 69 71 73 75 77 79 81 83 85 87 89 91 93 Number of Ichnogenera (Treatise Part W) Ichnogeneric Diversity 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 n 23 r e 25 d 27 o 29 M 31 33 35 37 39 T 41 43 i 45 47 m 49 e 51 53 55 57 59 61 c i o 63 z 65 o e 67 a l 69 a 71 P 73 75 77 79 81 83 n 85 a i r 87 b 89 m 91 a 93 C Number of Ichnogenera (Treatise Part W) -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

Advances in Understanding of Desiccation Tolerance of Lichens and Lichen-Forming Algae

plants Review Advances in Understanding of Desiccation Tolerance of Lichens and Lichen-Forming Algae Francisco Gasulla *, Eva M del Campo, Leonardo M. Casano and Alfredo Guéra * Department of Life Sciences, Universidad de Alcalá, Alcalá de Henares, 28802 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (E.M.d.C.); [email protected] (L.M.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (F.G.); [email protected] (A.G.) Abstract: Lichens are symbiotic associations (holobionts) established between fungi (mycobionts) and certain groups of cyanobacteria or unicellular green algae (photobionts). This symbiotic association has been essential in the colonization of terrestrial dry habitats. Lichens possess key mechanisms involved in desiccation tolerance (DT) that are constitutively present such as high amounts of polyols, LEA proteins, HSPs, a powerful antioxidant system, thylakoidal oligogalactolipids, etc. This strategy allows them to be always ready to survive drastic changes in their water content. However, several studies indicate that at least some protective mechanisms require a minimal time to be induced, such as the induction of the antioxidant system, the activation of non-photochemical quenching including the de-epoxidation of violaxanthin to zeaxanthin, lipid membrane remodeling, changes in the proportions of polyols, ultrastructural changes, marked polysaccharide remodeling of the cell wall, etc. Although DT in lichens is achieved mainly through constitutive mechanisms, the induction of protection mechanisms might allow them to face desiccation stress in a better condition. The proportion and relevance of constitutive and inducible DT mechanisms seem to be related to the ecology at which lichens are adapted to. Citation: Gasulla, F.; del Campo, E.M; Casano, L.M.; Guéra, A. -

Evolutionary Processes Transpiring in the Stages of Lithopanspermia Ian Von Hegner

Evolutionary processes transpiring in the stages of lithopanspermia Ian von Hegner To cite this version: Ian von Hegner. Evolutionary processes transpiring in the stages of lithopanspermia. 2020. hal- 02548882v2 HAL Id: hal-02548882 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02548882v2 Preprint submitted on 5 Aug 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. HAL archives-ouvertes.fr | CCSD, April 2020. Evolutionary processes transpiring in the stages of lithopanspermia Ian von Hegner Aarhus University Abstract Lithopanspermia is a theory proposing a natural exchange of organisms between solar system bodies as a result of asteroidal or cometary impactors. Research has examined not only the physics of the stages themselves but also the survival probabilities for life in each stage. However, although life is the primary factor of interest in lithopanspermia, this life is mainly treated as a passive cargo. Life, however, does not merely passively receive an onslaught of stress from surroundings; instead, it reacts. Thus, planetary ejection, interplanetary transport, and planetary entry are only the first three factors in the equation. The other factors are the quality, quantity, and evolutionary strategy of the transported organisms. -

Full Property Address Primary Liable

Full Property Address Primary Liable party name 2019 Opening Balance Current Relief Current RV Write on/off net effect 119, Westborough, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1LP The Edinburgh Woollen Mill Ltd 35249.5 71500 4 Dnc Scaffolding, 62, Gladstone Lane, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 7BS Dnc Scaffolding Ltd 2352 4900 Ebony House, Queen Margarets Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 2YH Mj Builders Scarborough Ltd 6240 Small Business Relief England 13000 Walker & Hutton Store, Main Street, Irton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 4RH Walker & Hutton Scarborough Ltd 780 Small Business Relief England 1625 Halfords Ltd, Seamer Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 4DH Halfords Ltd 49300 100000 1st 2nd & 3rd Floors, 39 - 40, Queen Street, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1HQ Yorkshire Coast Workshops Ltd 10560 DISCRETIONARY RELIEF NON PROFIT MAKING 22000 Grosmont Co-Op, Front Street, Grosmont, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO22 5QE Grosmont Coop Society Ltd 2119.9 DISCRETIONARY RURAL RATE RELIEF 4300 Dw Engineering, Cholmley Way, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO22 4NJ At Cowen & Son Ltd 9600 20000 17, Pier Road, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO21 3PU John Bull Confectioners Ltd 9360 19500 62 - 63, Westborough, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1TS Winn & Co (Yorkshire) Ltd 12000 25000 Des Winks Cars Ltd, Hopper Hill Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 3YF Des Winks [Cars] Ltd 85289 173000 1, Aberdeen Walk, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1BA Thomas Of York Ltd 23400 48750 Waste Transfer Station, Seamer, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, -

Letter to the Editor

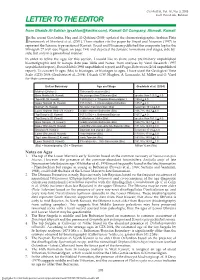

GeoArabia, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2005 Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain LETTER TO THE EDITOR from Ghaida Al-Sahlan ([email protected]), Kuwait Oil Company, Ahmadi, Kuwait n the recent GeoArabia, Haq and Al-Qahtani (2005) updated the chronostratigraphic Arabian Plate Iframework of Sharland et al. (2001). These studies cite the paper by Yousif and Nouman (1997) to represent the Jurassic type section of Kuwait. Yousif and Nouman published the composite log for the Minagish-27 well (see Figure on page 194) and depicted the Jurassic formations and stages, side-by- side, but only in a generalized manner. In order to refine the ages for this section, I would like to share some preliminary unpublished biostratigraphic and Sr isotope data (see Table and Notes) from analyses by Varol Research (1997 unpublished report), ExxonMobil (1998 unpublished report) and Fugro-Robertson (2004 unpublished report). To convert Sr ages (Ma) to biostages, or biostages to ages, I have used the Geological Time Scale (GTS) 2004 (Gradstein et al., 2004). I thank G.W. Hughes, A. Lomando, M. Miller and O. Varol for their comments. Unit or Boundary Age and Stage Gradstein et al. (2004) Makhul (Offshore) Tithonian-Berriasian (Bio) Base Makhul (N. Kuwait) No younger than Tithonian (Bio) greater than 145.5 + 4.0 Top Hith (W. Kuwait) 150.0 (Sr) = c. Tithonian/Kimmeridgian ? 150.8 + 4.0 Upper Najmah (S. Kuwait) 155.0 (Sr) = c. Kimmeridgian/Oxfordian 155.7 + 4.0 Najmah (N. Kuwait) No older than Oxfordian (Bio) less than 161.2 + 4.0 Lower Najmah Shale (N. Kuwait) middle and late Bathonian (Bio) 166.7 to 164.7 + 4.0 Top Sargelu (S. -

And Early Jurassic Sediments, and Patterns of the Triassic-Jurassic

and Early Jurassic sediments, and patterns of the Triassic-Jurassic PAUL E. OLSEN AND tetrapod transition HANS-DIETER SUES Introduction parent answer was that the supposed mass extinc- The Late Triassic-Early Jurassic boundary is fre- tions in the tetrapod record were largely an artifact quently cited as one of the thirteen or so episodes of incorrect or questionable biostratigraphic corre- of major extinctions that punctuate Phanerozoic his- lations. On reexamining the problem, we have come tory (Colbert 1958; Newell 1967; Hallam 1981; Raup to realize that the kinds of patterns revealed by look- and Sepkoski 1982, 1984). These times of apparent ing at the change in taxonomic composition through decimation stand out as one class of the great events time also profoundly depend on the taxonomic levels in the history of life. and the sampling intervals examined. We address Renewed interest in the pattern of mass ex- those problems in this chapter. We have now found tinctions through time has stimulated novel and com- that there does indeed appear to be some sort of prehensive attempts to relate these patterns to other extinction event, but it cannot be examined at the terrestrial and extraterrestrial phenomena (see usual coarse levels of resolution. It requires new fine- Chapter 24). The Triassic-Jurassic boundary takes scaled documentation of specific faunal and floral on special significance in this light. First, the faunal transitions. transitions have been cited as even greater in mag- Stratigraphic correlation of geographically dis- nitude than those of the Cretaceous or the Permian junct rocks and assemblages predetermines our per- (Colbert 1958; Hallam 1981; see also Chapter 24). -

Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) Cold-Water Idoceratids (Ammonoidea) from Southern Coahuila, Northeastern Mexico, Associated with Boreal Bivalves and Belemnites

REVISTA MEXICANA DE CIENCIAS GEOLÓGICAS Kimmeridgian cold-water idoceratids associated with Boreal bivalvesv. 32, núm. and 1, 2015, belemnites p. 11-20 Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) cold-water idoceratids (Ammonoidea) from southern Coahuila, northeastern Mexico, associated with Boreal bivalves and belemnites Patrick Zell* and Wolfgang Stinnesbeck Institute for Earth Sciences, Heidelberg University, Im Neuenheimer Feld 234, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany. *[email protected] ABSTRACT et al., 2001; Chumakov et al., 2014) was followed by a cool period during the late Oxfordian-early Kimmeridgian (e.g., Jenkyns et al., Here we present two early Kimmeridgian faunal assemblages 2002; Weissert and Erba, 2004) and a long-term gradual warming composed of the ammonite Idoceras (Idoceras pinonense n. sp. and trend towards the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary (e.g., Abbink et al., I. inflatum Burckhardt, 1906), Boreal belemnites Cylindroteuthis 2001; Lécuyer et al., 2003; Gröcke et al., 2003; Zakharov et al., 2014). cuspidata Sachs and Nalnjaeva, 1964 and Cylindroteuthis ex. gr. Palynological data suggest that the latest Jurassic was also marked by jacutica Sachs and Nalnjaeva, 1964, as well as the Boreal bivalve Buchia significant fluctuations in paleotemperature and climate (e.g., Abbink concentrica (J. de C. Sowerby, 1827). The assemblages were discovered et al., 2001). in inner- to outer shelf sediments of the lower La Casita Formation Upper Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous marine associations contain- at Puerto Piñones, southern Coahuila, and suggest that some taxa of ing both Tethyan and Boreal elements [e.g. ammonites, belemnites Idoceras inhabited cold-water environments. (Cylindroteuthis) and bivalves (Buchia)], were described from numer- ous localities of the Western Cordillera belt from Alaska to California Key words: La Casita Formation, Kimmeridgian, idoceratid ammonites, (e.g., Jeletzky, 1965), while Boreal (Buchia) and even southern high Boreal bivalves, Boreal belemnites.