State Secrets: China’S Legal Labyrinth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 INTERIM REPORT * Bank of Chongqing Co., Ltd

BANK OF CHONGQING CO., LTD.* 重慶銀行股份有限公司* (A joint stock company incorporated in the People's Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 1963) (Stock Code of Preference Shares: 4616) 2018 INTERIM REPORT * Bank of Chongqing Co., Ltd. is not an authorized institution within the meaning of the Banking Ordinance (Chapter 155 of Laws of Hong Kong), not subject to the supervision of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, and not authorized to carry on banking and/or deposit-taking business in Hong Kong. CONTENTS 1. Corporate Information 2 2. Financial Highlights 3 3. Management Discussions and Analysis 6 3.1 Environment and Outlook 6 3.2 Financial Review 8 3.3 Business Overview 40 3.4 Employees and Human Resources 51 Management 3.5 Risk Management 52 3.6 Capital Management 58 4. Change in Share Capital and Shareholders 61 5. Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management 65 6. Significant Events 67 7. Report on Review of Interim Financial Information 69 8. Interim Condensed Consolidated Financial 70 Information and Notes Thereto 9. Unaudited Supplementary Financial Information 155 10. Organizational Chart 158 11. List of Branch Outlets 159 12. Definitions 167 Corporate Information Legal Name and Abbreviation in Chinese Date and Registration Authority of 重慶銀行股份有限公司 (Abbreviation: 重慶銀行) Initial Incorporation September 2, 1996 Name in English Administration for Industry and Bank of Chongqing Co., Ltd. Commerce of Chongqing, the PRC Legal Representative Unified Social Credit Code of Business License LIN Jun 91500000202869177Y Authorized Representatives Financial License Registration Number RAN Hailing B0206H250000001 WONG Wah Sing Auditors Secretary to the Board International: PENG Yanxi PricewaterhouseCoopers Address: 22/F, Prince’s Building, Central, Joint Company Secretaries Hong Kong WONG Wah Sing HO Wing Tsz Wendy Domestic: PricewaterhouseCoopers Zhong Tian LLP Registered Address and Postal Code Address: 11/F, PricewaterhouseCoopers Center, No. -

1 Introduction Chinese Citizens Continue to Face Substantial Obstacles in Seeking Remedies to Government Actions That Violate Th

1 ACCESS TO JUSTICE Introduction Chinese citizens continue to face substantial obstacles in seeking remedies to government actions that violate their legal rights and constitutionally protected freedoms. International human rights standards require effective remedies for official violations of citi- zens’ rights. Article 8 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that ‘‘Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the funda- mental rights granted him by the constitution or by law.’’ 1 Article 2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which China has signed but not yet ratified, requires that all parties to the ICCPR ensure that persons whose rights or free- doms are violated ‘‘have an effective remedy, notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity.’’ 2 The Third Plenum and Judicial Reform The November 2013 Chinese Communist Party Central Com- mittee Third Plenum Decision on Certain Major Issues Regarding Comprehensively Deepening Reforms (Third Plenum Decision) con- tained several items relating to judicial system reform.3 In June 2014, the office of the Party’s Central Leading Small Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reform announced that six provinces and municipalities—Shanghai, Guangdong, Jilin, Hubei, Hainan, and Qinghai—would serve as pilot sites for certain judicial reforms, including divesting local governments of their control over local court funding and appointments and centralizing -

I CHINESE INVESTMENT in the UNITED STATES: IMPACTS AND

i CHINESE INVESTMENT IN THE UNITED STATES: IMPACTS AND ISSUES FOR POLICYMAKERS HEARING BEFORE THE U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION THURSDAY, JANUARY 26, 2017 Printed for use of the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: www.uscc.gov UNITED STATES-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION WASHINGTON: 2017 ii U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION CAROLYN BARTHOLOMEW, CHAIRMAN HON. DENNIS C. SHEA, VICE CHAIRMAN Commissioners: ROBIN CLEVELAND HON. JONATHAN STIVERS HON. BYRON L. DORGAN HON. JAMES TALENT HON. CARTE P. GOODWIN DR. KATHERINE C. TOBIN DANIEL M. SLANE MICHAEL R. WESSEL MICHAEL R. DANIS, Executive Director The Commission was created on October 30, 2000 by the Floyd D. Spence National Defense Authorization Act for 2001 § 1238, Public Law No. 106-398, 114 STAT. 1654A-334 (2000) (codified at 22 U.S.C. § 7002 (2001), as amended by the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for 2002 § 645 (regarding employment status of staff) & § 648 (regarding changing annual report due date from March to June), Public Law No. 107-67, 115 STAT. 514 (Nov. 12, 2001); as amended by Division P of the “Consolidated Appropriations Resolution, 2003,” Pub L. No. 108-7 (Feb. 20, 2003) (regarding Commission name change, terms of Commissioners, and responsibilities of the Commission); as amended by Public Law No. 109- 108 (H.R. 2862) (Nov. 22, 2005) (regarding responsibilities of Commission and applicability of FACA); as amended by Division J of the “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008,” Public Law Nol. -

28. Rights Defense and New Citizen's Movement

JOBNAME: EE10 Biddulph PAGE: 1 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Fri May 10 14:09:18 2019 28. Rights defense and new citizen’s movement Teng Biao 28.1 THE RISE OF THE RIGHTS DEFENSE MOVEMENT The ‘Rights Defense Movement’ (weiquan yundong) emerged in the early 2000s as a new focus of the Chinese democracy movement, succeeding the Xidan Democracy Wall movement of the late 1970s and the Tiananmen Democracy movement of 1989. It is a social movement ‘involving all social strata throughout the country and covering every aspect of human rights’ (Feng Chongyi 2009, p. 151), one in which Chinese citizens assert their constitutional and legal rights through lawful means and within the legal framework of the country. As Benney (2013, p. 12) notes, the term ‘weiquan’is used by different people to refer to different things in different contexts. Although Chinese rights defense lawyers have played a key role in defining and providing leadership to this emerging weiquan movement (Carnes 2006; Pils 2016), numerous non-lawyer activists and organizations are also involved in it. The discourse and activities of ‘rights defense’ (weiquan) originated in the 1990s, when some citizens began using the law to defend consumer rights. The 1990s also saw the early development of rural anti-tax movements, labor rights campaigns, women’s rights campaigns and an environmental movement. However, in a narrow sense as well as from a historical perspective, the term weiquan movement only refers to the rights campaigns that emerged after the Sun Zhigang incident in 2003 (Zhu Han 2016, pp. 55, 60). The Sun Zhigang incident not only marks the beginning of the rights defense movement; it also can be seen as one of its few successes. -

Climate-Change Journalism in China: Opportunities for International

Climate-change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation By Sam Geall Foreword by Hu Shuli 中国气候变化报道: 国际合作中的机遇 山姆·吉尔 序——胡舒立 Climate-change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation 中国气候变化报道:国际合作中的机遇 © International Media Support 2011. Any reproduction, modification, publication, transmission, transfer, sale distribution, display or exploitation of this information, in any form or by any means, or its storage in a retrieval system, whether in whole or in part, without the express written permission of the individual copyright holder is prohibited without prior approval by IMS. Cover image by Angel Hsu. © 国际媒体支持组织 版权所有 2011 任何媒体、网站或个人未经“国际媒体支持组织”的书面许可,不得引用、复 制、转载、摘编、发售、储存于检索系统,或以其他任何方式非法使用本报告全 部或部分内容。 封面照片由徐安琪摄。 International Media Support (IMS) Communications Unit, Nørregade 18, Copenhagen K 1165, Denmark Phone: +4588327000, Fax: +4533120099 Email: [email protected] www.i-m-s.dk Caixin Media Floor 15/16, Tower A, Winterless Center, No.1 Xidawanglu, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100026, P.R.China http://english.caing.com/ chinadialogue Suite 306 Grayston Centre, 28 Charles Square, London N1 6HT, United Kingdom Phone: +442073244767 Email: [email protected] www.chinadialogue.net Climate-change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation By Sam Geall1 Foreword by Hu Shuli2 p4 1. Sam Geall is deputy editor of chinadialogue. The author acknowledges generous contributions to the research and analysis in this report from Li Hujun, Wang Haotong, Eliot Gao and Lisa Lin. Essential input and support were also provided by Martin Breum, Martin Gottske, Isabel Hilton, Tan Copsey, Li Dawei, Ma Ling, Hu Shuli, Bruce Lewenstein and Jia Hepeng. 2. Hu Shuli is editor-in-chief of Caixin Media (the Beijing-based media group that publishes Century Weekly and China Reform), the former founding editor of Caijing magazine and a prominent investigative journalist and commentator. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 2007 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–026 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIM WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. -

China's Foreign Policy Dilemma

February 2013 ANALYSIS LINDA JAKOBSON China’s Foreign Policy Program Director East Asia Dilemma Tel: +61 2 8238 9070 [email protected] E xecutive summary Foreign policy will not be a top priority of China’s new leader Xi Jinping. Xi is under pressure from many sectors of society to tackle China’s formidable domestic problems. To stay in power Xi must ensure continued economic growth and social stability. Due to the new leadership’s preoccupation with domestic issues, Chinese foreign policy can be expected to be reactive. This may have serious consequences because of the potentially explosive nature of two of China’s most pressing foreign policy challenges: how to decrease tensions with Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and with Southeast Asian states over territorial claims in the South China Sea. A lack of attention by China’s senior leaders to these sovereignty disputes is a recipe for disaster. If a maritime or aerial incident occurs, nationalist pressure will narrow the room for manoeuvre of leaders in each of the countries involved in the incident. There are numerous foreign and security policy actors within China who favour Beijing taking a more forceful stance in its foreign policy. Regional stability could be at risk if China’s new leadership merely reacts as events unfold, as has too often been the case in recent years. LOWY INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL POLICY 31 Bligh Street Sydney NSW 2000 Tel: +61 2 8238 9000 Fax: +61 2 8238 9005 www.lowyinstitute.org The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent policy think tank. -

Maria Khayutina • [email protected] the Tombs

Maria Khayutina [email protected] The Tombs of Peng State and Related Questions Paper for the Chicago Bronze Workshop, November 3-7, 2010 (, 1.1.) () The discovery of the Western Zhou period’s Peng State in Heng River Valley in the south of Shanxi Province represents one of the most fascinating archaeological events of the last decade. Ruled by a lineage of Kui (Gui ) surname, Peng, supposedly, was founded by descendants of a group that, to a certain degree, retained autonomy from the Huaxia cultural and political community, dominated by lineages of Zi , Ji and Jiang surnames. Considering Peng’s location right to the south of one of the major Ji states, Jin , and quite close to the eastern residence of Zhou kings, Chengzhou , its case can be very instructive with regard to the construction of the geo-political and cultural space in Early China during the Western Zhou period. Although the publication of the full excavations’ report may take years, some preliminary observations can be made already now based on simplified archaeological reports about the tombs of Peng ruler Cheng and his spouse née Ji of Bi . In the present paper, I briefly introduce the tombs inventory and the inscriptions on the bronzes, and then proceed to discuss the following questions: - How the tombs M1 and M2 at Hengbei can be dated? - What does the equipment of the Hengbei tombs suggest about the cultural roots of Peng? - What can be observed about Peng’s relations to the Gui people and to other Kui/Gui- surnamed lineages? 1. General Information The cemetery of Peng state has been discovered near Hengbei village (Hengshui town, Jiang County, Shanxi ). -

CHINA 1.0 CHINA 2.0 CHINA 3.0 Edited by Mark Leonard Afterword by François Godement and Jonas Parello-Plesner ABOUT ECFR ABOUT ECFR’S CHINA PROGRAMME

CHINA 1.0 CHINA 2.0 CHINA 3.0 edited by Mark Leonard Afterword by François Godement and Jonas Parello-Plesner ABOUT ECFR ABOUT ECFR’S CHINA PROGRAMME The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) is ECFR’s China programme aims to develop a smarter the first pan-European think-tank. Launched in October European strategy towards China. It provides 2007, its objective is to conduct research and promote information about China and raises awareness about informed debate across Europe on the development the increasing power imbalance between China and of coherent, effective and values-based European Europe and the lack of prioritisation, consistency and foreign policy. co-ordination in EU China policy. ECFR has developed a strategy with three distinctive The report A Power Audit of EU-China relations elements that define its activities: (April 2009) has become a reference on the issue of European China policy. Since then, ECFR has also •A pan-European Council. ECFR has brought together published several policy briefs such as A Global China a distinguished Council of over one hundred and Policy (June 2010), The Scramble for Europe (April 2011) seventy Members – politicians, decision makers, and China and Germany: Why the emerging special thinkers and business people from the EU’s member relationship matters for Europe (May 2012) and the states and candidate countries – which meets once essay China at the Crossroads (April 2012). a year as a full body. Through geographical and thematic task forces, members provide ECFR staff Together with Asia Centre, ECFR also publishes China with advice and feedback on policy ideas and help Analysis, a quarterly review of Chinese sources that with ECFR’s activities within their own countries. -

Business Risk of Crime in China

Business and the Ris k of Crime in China Business and the Ris k of Crime in China Roderic Broadhurst John Bacon-Shone Brigitte Bouhours Thierry Bouhours assisted by Lee Kingwa ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 3 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Business and the risk of crime in China : the 2005-2006 China international crime against business survey / Roderic Broadhurst ... [et al.]. ISBN: 9781921862533 (pbk.) 9781921862540 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Crime--China--21st century--Costs. Commercial crimes--China--21st century--Costs. Other Authors/Contributors: Broadhurst, Roderic G. Dewey Number: 345.510268 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: The gods of wealth enter the home from everywhere, wealth, treasures and peace beckon; designer unknown, 1993; (Landsberger Collection) International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Foreword . vii Lu Jianping Preface . ix Acronyms . xv Introduction . 1 1 . Background . 25 2 . Crime and its Control in China . 43 3 . ICBS Instrument, Methodology and Sample . 79 4 . Common Crimes against Business . 95 5 . Fraud, Bribery, Extortion and Other Crimes against Business . -

China – Labour Regulations – Working Conditions – Industrial Relations

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: CHN32293 Country: China Date: 29 August 2007 Keywords: China – Labour regulations – Working conditions – Industrial relations This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Are there labour laws in China that regulate the hours of work? 2. Are there labour laws that regulate salary? 3. Are there labour laws that regulate a worker’s conditions of work such as sick pay? 4. What is the attitude of the Chinese authorities towards workers demanding better working conditions such as a reduction in working hours and an increase in salary? RESPONSE 1. Are there labour laws in China that regulate the hours of work? China has a 1994 Labour Law that includes articles to regulate hours of work in its Chapter 4 (Labour Law of the People’s Republic of China 1994, adopted at the Eighth Meeting of the Standing Committee of the Eighth National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China on 5 July 1994, and entering into force on 1 January 1995, All-China Federation of Trade Unions websitehttp://www.acftu.org.cn/labourlaw.htm – Accessed 23 August 2007 – Attachment 1). -

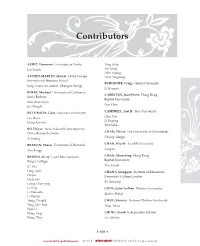

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New