Calibrating Laboratory Conditions to the New Normal in Union Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

DJ Song list Songs by Artist DJ Song list Title Versions Title Versions Title Versions Title Versions -- 360 Ft Pez 50 Cent Adam & The Ants Al Green -- 360 Ft Pez - Live It Up DJ 21 Questions DJ Ant Music DJ Let's Stay Together We -- Chris Brown Ft Lil Wayne Candy Shop DJ Goody Two Shoes DJ Al Stuart -- Chris Brown Ft Lil Wayne - DJ Hustler's Ambition DJ Stand And Deliver DJ Year Of The Cat DJ Loyal If I Can't DJ Adam Clayton & Larry Mullen Alan Jackson -- Illy In Da Club DJ Theme From Mission DJ Hi Chattahoochee DJ -- Illy - Tightrope (Clean) DJ Just A Li'l Bit DJ Impossible Don't Rock The Jukebox DJ -- Jason Derulo Ft Snoop Dog 50 Cent Feat Justin Timberlake Adam Faith Gone Country DJ -- Jason Derulo Ft Snoop Dog DJ Ayo Technology DJ Poor Me DJ Livin' On Love DJ - Wiggle 50 Cent Feat Mobb Deep Adam Lambert Alan Parsons Project -- Th Amity Afflication Outta Control DJ Adam Lambert - Better Than I DJ Eye In The Sky 2010 Remix DJ -- Th Amity Afflication - Dont DJ Know Myself 50 Cent Ft Eminem & Adam Levin Alanis Morissette Lean On Me(Warning) If I Had You DJ 50 Cent Ft Eminem & Adam DJ Hand In My Pocket DJ - The Potbelleez Whataya Want From Me Ch Levine - My Life (Edited) Ironic DJ Shake It - The Potbelleez DJ Adam Sandler 50Cent Feat Ne-Yo You Oughta Know DJ (Beyonce V Eurythmics Remix (The Wedding Singer) I DJ Baby By Me DJ Alannah Myles Sweet Dreams DJ Wanna Grow Old With You 60 Ft Gossling Black Velvet DJ 01 - Count On Me - Bruno Marrs Adele 360 Ft Gossling - Price Of DJ Albert Lennard Count On Me - Bruno Marrs DJ Fame Adele - Skyfall DJ Springtime In L.A. -

Audio + Video 6/8/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to Be Taken Directly to the Sell Sheet

New Releases WEA.CoM iSSUE 11 JUNE 8 + JUNE 15 , 2010 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word audio + video 6/8/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date CD- WB 522739 AGAINST ME! White Crosses $13.99 6/8/10 N/A CD- White Crosses (Limited WB 524438 AGAINST ME! Edition) $13.99 6/8/10 5/19/10 White Crosses (Vinyl WB A-522739 AGAINST ME! w/Download Card) $18.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- CUR 78977 BRICE, LEE Love Like Crazy $18.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 DV- WRN 523924 CUMMINS, DAN Crazy With A Capital F (DVD) $16.95 6/8/10 5/12/10 WB A-46269 FAILURE Fantastic Planet (2LP) $24.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 Selections From The Original Broadway Cast Recording CD- 'American Idiot' Featuring REP 524521 GREEN DAY Green Day $18.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- RRR 177972 HAIL THE VILLAIN Population: Declining $13.99 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- REP 519905 IYAZ Replay $9.94 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- FBY 524007 MCCOY, TRAVIE Lazarus $13.99 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- FBY 524670 MCCOY, TRAVIE Lazarus (Amended) $13.99 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- ATL 522495 PLIES Goon Affiliated $18.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- ATL 522497 PLIES Goon Affiliated (Amended) $18.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 The Twilight Saga: Eclipse CD- Original Motion Picture ATL 523836 VARIOUS ARTISTS Soundtrack $18.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 The Twilight Saga: -

Street Art Gets Buckwild in Venice

July 14-27, 2010 \ Volume 20 \ Issue 27 \ Always Free Film | Music | Culture Street Art Gets Buckwild in Venice ©2010 CAMPUS CIRCLE • (323) 939-8477 • 5042 WILSHIRE BLVD., #600 LOS ANGELES, CA 90036 • WWW.CAMPUSCIRCLE.COM • ONE FREE COPY PER PERSON Join CAMPUS CIRCLE www.campuscircle.com CALLING ALL INTERNS Are you looking to break into… Journalism? Photography? Advertising & Marketing? CAMPUS CIRCLE is seeking a few enthusiastic, creative journalists, photographers and aspiring sales people to join our team. Intern Perks Include: Free Movie Screenings, Free Music and an opportunity to explore L.A. like never before! Take the next step in your career: [email protected] 2 Campus Circle 7.14.10 - 7.27.10 YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN • PANTAGES • 4.870” X 5.900” CAMPUS CIRCLE • PUB DATE: 7.25.2010 Join CAMPUS CIRCLE www.campuscircle.com campus circle INSIDE campus CIRCLE July 14 - July 27, 2010 Vol. 20 Issue 27 Editor-in-Chief 8 Jessica Koslow [email protected] Managing Editor Yuri Shimoda 6 16 [email protected] 04 FILM ROSENCRANTZ AND Film Editor GUILDENSTERN ARE UNDEAD Jessica Koslow Dark comedy sinks its teeth into the [email protected] vampire genre. Cover Designer 04 FILM SCREEN SHOTS Sean Michael 06 FILM INCEPTION Editorial Interns Christopher Nolan directs Leonardo Lynda Correa, Christine Hernandez, DiCaprio in this enigmatic thriller. Arit John, Marvin Vasquez 06 FILM DVD DISH 08 FILM THE SORCERER’S APPRENTICE Contributing Writers Jay Baruchel makes magic with Christopher Agutos, Geoffrey Altrocchi, Hollywood powerhouses. Jonathan Bautts, Scott Bedno, Scott Bell, Zach Bourque, Erica Carter, Richard Castañeda, 08 FILM PROJECTIONS Joshua Chilton, Cesar Cruz, Nick Day, Natasha Desianto, Rebecca Elias, Denise Guerra, James 09 FILM MOVIE REVIEWS Famera, Mari Fong, Stephanie Forshee, A.J. -

United States District Court Criminal Complaint I

AO 91 (REV.5/85) Criminal Complaint AUSA Sheri H. Mecklenburg, (312) 469-6030 W4444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS, EASTERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I DOMINGO BLOUNT (a/k/a Mingo, John White, CASE NUMBER: David Roose) and Defendants named in the attached list UNDER SEAL (Name and Address of Defendant) I, the undersigned complainant being duly sworn state the following is true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief: Count One: Beginning no later than in or about March 2010, and continuing until the present, DOMINGO BLOUNT (a/k/a Mingo, John White, David Roose), GABRIEL BRIDGES (a/k/a Gabe Bridges), CHARLES THOMAS (a/k/a Big C, Willie Thomas, Walter Davis, Charles Thomas, Jr., Thomas Brown, Bob Goodfella, Bobby Jones, Samuel Cole, Deon Davis, Charles Williams, Charles Bullock), RICHARD HOPKINS (a/k/a “Rich”), MYRON GRISBY (a/k/a Myron K. Grigsby, Jr., Zane), LAMAR BLOUNT (a/k/a Lamont Blunt, Tyrone Blount, Blount), DEMETRIUS COLE (a/k/a Meechie) and OMESHIA CRUSOE (a/k/a “O”) conspired with each other, and with others known and unknown, to knowingly and intentionally possess with intent to distribute and distribute a controlled substance, namely 1 kilogram or more of mixtures and substances containing a detectable amount of heroin, a Schedule I Narcotic Drug Controlled Substance, 500 grams or more of cocaine, a Schedule II Narcotic Drug Controlled Substance, in violation of Title 21, United States Code, Section 841(a)(1), in violation of Title 21, United States Code, Section 846. -

Global Monthly

A publication from June 2012 Volume 01 | Issue 04 global europe.autonews.com/globalmonthly monthly Your source for everything automotive. The Americanization of Fiat Troubles in Europe have made Chrysler the dominant player in the alliance © 2012 Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved. US flag: © NIcholas B, fotolia.com March 2012 A publication from Ex-Saabglobal monthlyboss dAtA Muller wants Volume 01 | Issue 01 SUV for Spyker Infiniti makes WESTERN EUROPE SALES BY MODEL, 9 MONTHSbig movesbrought to you courtesy of www.jato.com in Europe JATO data shows 9 months 9 months Unit Percent 9 months 9 months Unit Percent 2011 2010 change change 2011 2010 change change Europe winners Scenic/Grand Scenic ......... 116,475 137,093 –20,618 –15% A1 ................................. 73,394 6,307 +67,087 – Espace/Grand Espace ...... 12,656 12,340 +316 3% A3/S3/RS3 ..................... 107,684 135,284 –27,600 –20% in first 4 months Koleos ........................... 11,474 9,386 +2,088 22% A4/S4/RS4 ..................... 120,301 133,366 –13,065 –10% Kangoo ......................... 24,693 27,159 –2,466 –9% A6/S6/RS6/Allroad ......... 56,012 51,950 +4,062 8% Trafic ............................. 8,142 7,057 +1,085 15% A7 ................................. 14,475 220 +14,255 – Other ............................ 592 1,075 –483 –45% A8/S8 ............................ 6,985 5,549 +1,436 26% Total Renault brand ........ 747,129 832,216 –85,087 –10% TT .................................. 14,401 13,435 +966 7% RENAULT ........................ 898,644 994,894 –96,250 –10% A5/S5/RS5 ..................... 54,387 59,925 –5,538 –9% RENAULT-NISSAN ............ 1,239,749 1,288,257 –48,508 –4% R8 ................................ -

H Crave Kelis Uffie Feat. Pharrell Ne-Yo Blu Cantrell Timbaland Kelly

h Crave gTF' .:i Name Artist Genre Acapella Kelis R&B Add Suv (Armand Van Helden Vocal) Uffie Feat. Pharrell R&B Alejandro Lady Caga R&B Around The Way Cirl LL CooI J R&B ....Baby One More Time Britney Spears R&B Beautifu I Snoop Dogg Feat. Pharrell & Uncle C... R&B Beautiful Monster Ne-Yo R&B Billionaire Travie McCoy R&B Breathe Blu Cantrell R&B The Bum Song Tommy Trash & Tom Piper R&B C'mon N'Ride lt Quad City DJ's R&B Carry Out INew Version] Timbaland R&B Commander [Radio Edit] Kelly Rowland R&B Controversy Prince R&B Do You Remember Jay Sean R&B Do You Think About Me 50 Cent R&B Don't Be Cruel Bobby Brown R&B Drop lt Low [Explicit Version] Ester Dean R&B Dynamite Taio Cruz R&B Find Your Love Drake R&B Flashback Calvin Harris R&B Freefallin' (Denzal Park Remix) Zo€ Badwi R&B Freek'n You Jodeci R&B Cangsta Bell Biv DeVoe R&B Gangsta's Paradise Coolio Feat. LV R&B Cifted (Steve Aoki Remix) N.A.S.A. R&B Heartbreaker (Laidback Luke Remix) MSTRKRFT Feat. John Legend R&B Hotel Room Service Pirbull R&B Hustler Simian Mobile Disco R&B Hypnotize The Notorious B.l.C. R&B I Can Transform Ya Chris Brown R&B I Cotta Feeling The Black Eyed Peas R&B l'm The lsh (Havana Brown Remix) DJ Class R&B lf You Had My Love Jennifer Lopez R&B ln My Head Jason Derulo R&B ls lt Cood To You Teddy Riley Feat. -

Audio + Video 6/22/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to Be Taken Directly to the Sell Sheet

New Releases WEA.CoM iSSUE 12 JUNE 22 + JUNE 29, 2010 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word audio + video 6/22/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date CX- ANDERSON, NON 524055 LAURIE Homeland (CD/DVD) $23.98 6/22/10 5/26/10 B.o.B Presents: The Adventures of Bobby Ray ATL A-518903 B.O.B. (Vinyl) $22.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 The Great Ray Charles (180 ACG A-1259 CHARLES, RAY Gram Vinyl) $24.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 CD- TSG 25486-D CHESNUTT, MARK Outlaw $17.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 REP A-47736 CLAPTON, ERIC August (Vinyl) $22.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 Coltrane Jazz (180 Gram ACG A-1354 COLTRANE, JOHN Vinyl) $24.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 Plays The Blues (180 Gram ACG A-1382 COLTRANE, JOHN Vinyl) $24.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 CX- LYNYRD Live From Freedom Hall RLP 177815 SKYNYRD (CD/DVD) $24.98 6/22/10 5/26/10 DV- LYNYRD RLP 109169 SKYNYRD Live From Freedom Hall (DVD) $14.99 6/22/10 5/26/10 ROBERT CD- RANDOLPH & THE WB 511230 FAMILY BAND We Walk This Road $13.99 6/22/10 6/2/10 CD- SMITH, AARON MFL 524761 NIGEL Everyone Loves To Dance $13.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 CD- NEK 524367 UFFIE Sex Dreams and Denim Jeans $13.99 6/22/10 6/2/10 CD- MFL 524463 VARIOUS ARTISTS Giggling & Laughing $13.98 6/22/10 6/2/10 CD- FBY 524346 VERSA EMERGE Fixed At Zero $13.99 6/22/10 6/2/10 -

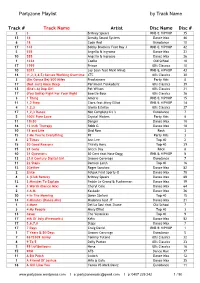

[email protected] L P: 0407 229 242 1 / 90 Partyzone Playlist by Track Name

Partyzone Playlist by Track Name Track # Track Name Artist Disc Name Disc # 2 3 Britney Spears RNB & HIPHOP 35 13 16 Sneaky Sound System Dance Max 46 6 18 Code Red Eurodance 10 17 143 Bobby Brackins Feat Ray J RNB & HIPHOP 42 5 555 Angello & Ingrosso Dance Max 23 10 555 Angello & Ingrosso Dance Max 26 1 1234 Coolio Old School10 17 1999 Prince 80's Classics10 10 2012 Jay Sean feat Nicki Minaj RNB & HIPHOP 43 18 (1,2,3,4,5) Senses Working Overtime XTC 80's Classics30 3 (I'm Gonna Be) 500 Miles Proclaimers Party Hits8 17 (Not Just) Knee Deep Parliment Funkadelic 80's Classics 39 13 (She's A) Bop Girl Pat Wilson 80's Classics 31 17 (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right Beastie Boys 80's Classics 36 3 1 Thing Amerie RNB & HIPHOP 15 11 1,2 Step Ciara feat Missy Elliot RNB & HIPHOP 14 4 1,2,3 Gloria Estefan 80's Classics 27 17 1,2,3 Dance Not Complete DJ 's Eurodance 7 5 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters Party Hits 8 11 11h30 Danger Dance Max18 16 12 Inch Therapy Robb G Dance Max 18 10 18 and Life Skid Row Rock 3 15 2 Me You're Everything 98° Party Hits 3 8 2 Times Ann Lee Top 40 2 15 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Top 40 29 15 21 Guns Green Day Rock 8 10 21 Questions 50 Cent feat Nate Dogg RNB & HIPHOP 8 13 21st Century Digital Girl Groove Coverage Eurodance 7 11 22 Steps Damien Leith Top 40 16 12 2Gether Roger Sanchez Dance Max 82 2 2nite Felguk Feat Sporty-O Dance Max 78 8 3 (Club Remix) Britney Spears Dance Max 68 12 3 Minutes To Explain Fedde Le Grand & Funkerman Dance Max 19 4 3 Words (Dance Mix) Cheryl Cole Dance Max 64 2 4 A.M Kaskade Dance Max -

Richard Harter

7747 5>R9M£R B9SA9J7 7^477 #5 ^August 7969 Tranquility Base Here, The Eagle Has Landed - 20 July 1969 Contents The Instrumentality Spieks, an editorial.......................... Richard Harter............... 4 Flower Power......................................................................................Susan Lewis.......................... 6 $150,000 Worth of Trivia............................................................. Jim Saklad........................... 8 The Clement Problem........................................................................ Richard Harter.................. 9 Minicon Report...................................................................................Tony Lewis.........................12 Department of Gloomy Panoramas of Contemporary Capitalism, Parts 3 and 4..................Dainis Bisenieks............ 15 Ronk3 being fanzine reviews.......................................................Mike Symes......................... 16 On Being the World’s Sixth Nuclear Power, An interview with J. R. M. Seitz...............................C. Whipple......................... 18 Word Games............................................................................................Harter and Lewis............ 23 Letters.................................................................................................. Divers Scribes.................24 Baycon Trip Report, Part I.............................................. *......... Cory Panshin..................... 33 Cover: A Proper Boskonian by Jack Gaughan Interior -

4032-49 Last to Know 112 4093-01 Love Song 311 4024-73

4032-49 LAST TO KNOW 112 4093-01 LOVE SONG 311 4024-73 YOU'LL JUST NEVER KNOW 702 7542-12 ALL I WANT IS YOU 911 4029-21 WE ARE THE WORLD 0 EIGHT 5 TEENS 5368-07 000 DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10 CC 4054-07 I'M NOT IN LOVE 10 CC 5363-08 000 THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE,THE 10 CC 9632-01 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 10.000 MANIACS 4016-15 THESE ARE DAYS 10.000 MANIACS 4012-31 TOO YOUNG 14 KARAT SOUL 8515-01 SIMON SAYS 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 8515-02 TRAIN,THE 1911 FRUITGUM CO. 4034-21 CALIFORNIA LOVE 2 PAC 4001-06 DEAR MAMA 2 PAC 4001-07 LIFE GOES ON 2 PAC 9632-02 ONE DAY AT A TIME 2 PAC 9632-03 RUNNING 2 PAC 8515-03 NO LIMIT 2 UNLIMITED 8515-04 REAL THING,THE 2 UNLIMITED 4027-71 WHY DON'T YOU DO IT FOR ME ? 22 - 20s 4093-03 KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN 4093-04 LET ME GO 3 DOORS DOWN 7544-06 WHEN I'M GONE 3 DOORS DOWN 4027-49 I DO(WANNA GET CLOSE TO YOU) 3 LW 4093-05 GOTTA BE YOU 3T 4093-06 I NEED YOU 3T 4093-07 WHY 3T 4012-30 LES FLEUR 4 HERO 9632-04 WHAT`S UP 4 NON-BLONDES 9632-05 SUKIYAKI 4 P.M 4012-24 BIG GIRLS DON'T CRY 4 SEASONS,THE 4012-25 CANDY GIRL 4 SEASONS,THE 4012-26 RAG DOLL 4 SEASONS,THE 4012-27 SHERRY 4 SEASONS,THE 4027-38 CHANCE 411,THE 4033-47 CHANCE 411,THE 4012-32 (I'D RATHER)BE ALONE Ⅳ XAMPLE 3139-07 AMUSEMENT PARK 50 CENT 3139-08 AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT 3107-01 CANDY SHOP FEAT. -

Dead End, No Turn Around, Danger Ahead: Challenges to the Future of Highway Funding Hearing Committee on Finance United States S

S. HRG. 114–276 DEAD END, NO TURN AROUND, DANGER AHEAD: CHALLENGES TO THE FUTURE OF HIGHWAY FUNDING HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCE UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 18, 2015 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Finance U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 20–336—PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 16:31 Jun 07, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 R:\DOCS\20336.000 TIMD COMMITTEE ON FINANCE ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah, Chairman CHUCK GRASSLEY, Iowa RON WYDEN, Oregon MIKE CRAPO, Idaho CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York PAT ROBERTS, Kansas DEBBIE STABENOW, Michigan MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming MARIA CANTWELL, Washington JOHN CORNYN, Texas BILL NELSON, Florida JOHN THUNE, South Dakota ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey RICHARD BURR, North Carolina THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland ROB PORTMAN, Ohio SHERROD BROWN, Ohio PATRICK J. TOOMEY, Pennsylvania MICHAEL F. BENNET, Colorado DANIEL COATS, Indiana ROBERT P. CASEY, Jr., Pennsylvania DEAN HELLER, Nevada MARK R. WARNER, Virginia TIM SCOTT, South Carolina CHRIS CAMPBELL, Staff Director JOSHUA SHEINKMAN, Democratic Staff Director (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 16:31 Jun 07, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 R:\DOCS\20336.000 TIMD C O N T E N T S OPENING STATEMENTS Page Hatch, Hon. -

A Corpus-Based Grammar of Spoken Pite Saami

A corpus-based grammar of spoken Pite Saami Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophischen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel vorgelegt von Joshua Karl Wilbur Kiel 2013 Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Ulrike Mosel Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. John Peterson Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 3. Mai 2013 Durch den zweiten Prodekan Prof. Dr. Marin Krieger zum Druck genehmigt: 19. August 2013 A corpus-based grammar of spoken Pite Saami Contents Table of Contents i List of Figures ix List of Tables xi Abbreviations and Symbols xv Acknowledgements xix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Pite Saami language and its speakers ............. 1 1.1.1 Linguistic genealogy ....................... 1 1.1.2 Names for Pite Saami ...................... 2 1.1.3 Geography ............................ 2 1.1.4 The state of the Pite Saami language .............. 6 1.2 Linguistic documentation of Pite Saami .............. 7 1.2.1 Previous studies ......................... 7 1.2.2 The Pite Saami Documentation Project corpus . 9 1.2.2.1 Collection methods ....................... 11 1.2.3 Using this description ...................... 13 1.2.3.1 Accountability and verifiability . 14 1.2.3.2 Accessing archived materials . 15 1.2.3.3 Explaining examples ...................... 15 1.2.3.4 Orthographic considerations . 16 1.3 Typological profile ......................... 22 2 Prosody 25 2.1 Monosyllabic word structure .................... 25 2.2 Multisyllablic word structure .................... 26 2.2.1 Word stress ............................ 27 2.2.2 Relevant prosodic domains ................... 27 2.2.2.1 Foot ............................... 28 i Table of Contents 2.2.2.2 Foot onset ............................ 28 2.2.2.3 V1 ................................ 28 2.2.2.4 The consonant center ....................