Geodiversity & Geoconservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biodiversity and Geodiversity Supplementary Planning Guidance (May 2018)

- Biodiversity and Geodiversity Supplementary Planning Guidance (May 2018) www.npt.gov.uk/ldp Sand Martin Bank © Barry Stewart Pipistrelle Bat © Laura Palmer Shrill Carder Bee © Mark Hipkin Contents Note to Reader 1 1 Introduction 3 2 Biodiversity and Geodiversity in Neath Port Talbot 5 2.1 What is 'Biodiversity' and 'Geodiversity'? 5 2.2 Biodiversity in Neath Port Talbot 5 2.3 Geodiversity in Neath Port Talbot 7 2.4 Green Infrastructure 8 3 Policy Context 11 3.1 National Policy Context 12 3.2 Local Policy Context 13 4 Policy Requirements 19 4.1 General Principles 19 5 Policy Implementation 21 5.1 Pre-Application Discussion 21 Supplementary Planning Guidance: Biodiversity and Geodiversity (May 2018) 5.2 Planning Application Submission 31 5.3 Decision / Determination 33 5.4 Monitoring, Management and Review 36 6 Contact Details 41 Appendices A SINC Criteria 1 B RIGS 11 C Specific Guidance on Wind Energy Schemes 15 D Compensation Scheme 21 E Glossary 27 Contents Supplementary Planning Guidance: Biodiversity and Geodiversity (May 2018) Note to Reader Note to Reader This document supplements and explains the policies in the Local Development Plan (LDP). The LDP was adopted by the Council on 27th January 2016 and forms the basis for decisions on land use planning in the County Borough up to 2026. This Supplementary Planning Guidance (SPG) has been prepared following a public consultation exercise that was undertaken in the Spring of 2018 and the guidance was adopted by the Council's Regeneration and Sustainable Development Cabinet Board on 18th May 2018. While only policies in the LDP have special status in the determination of planning applications, the SPG will be taken into account as a material consideration in the decision making process. -

Using Field-Based Geodiversity Information in Schools

USING FIELD-BASED GEODIVERSITY INFORMATION IN SCHOOLS. WHAT DO SCHOOLS WANT? HOW CAN RIGS AND CCW HELP? Cathie Brooks Alwyn Roberts A research project conducted for the Countryside Council for Wales October 2006 1 Content Acknowledgements Executive Summary Chapters 1 Project Rationale 2 Research Design 3 Geodiversity in the National Curriculum for Wales Primary 3-11 Secondary 11-16 Secondary 16-19 4 Existing Geodiversity Resources Primary 3-11 Secondary 11-16 Secondary 16-19 Teachers 16-19 Regional 5 Research into Future Geodiversity needs Primary 3-11 Secondary 11-19 Examination Board personnel Welsh Baccalaureate Qualification Residential Centre personnel 6 Initiatives undertaken by this project Foundation Phase KS 2 & 3 KS 4 7 Case Study, Anglesey Primary 3-11 Secondary 11-16 Secondary 16-19 8 Conclusions and Recommendations 2 Appendices 1 Acknowledgements 2 Distribution and size of entry of: WJEC Advanced GCE geography and geology; WBQ, North Wales, 2005 3 Geodiversity Audit 3A Primary 3-11 3B Secondary 11-16 3C Secondary 16-19 3D Cross-curricular components 4 Existing Geodiversity Resources, detail on specific resources 4A Primary 3-11: ESTA 4B Secondary 11-16: UKRIGS 4C Field sites in current educational use in North Wales 4D Regional: N Wales RIGS 5 Questionnaires for future geodiversity needs 5A1 & A2 Primary schools 5B1 & B2 Geography departments in Secondary schools 5C1 & C2 Geology departments in Secondary schools 6 Details of initiatives undertaken 6A Adapting North Wales RIGS Urban Geology Trails for educational use 6B Proposed KS4 Earth science submission for WJEC KS4 Science practical test 7 Questionnaires, Case Study, Anglesey 7D1 & D2 Primary schools 7E1 & E2 Science departments in Secondary schools 3 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Dr Stewart Campbell CCW, Mr Carl Atkinson CCW, Mrs Nerys Mullally CCW, Dr Margaret Wood, GeoMộn and Gwynedd and Mộn RIGS, for their insightful inputs into the design, development and writing of this project. -

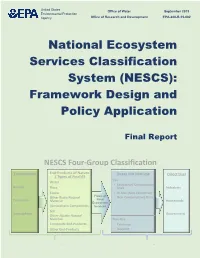

National Ecosystem Services Classification System (NESCS): Framework Design and Policy Application

United States Office of Water September 2015 Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development EPA-800-R-15-002 National Ecosystem Services Classification System (NESCS): Framework Design and Policy Application Final Report NESCS Four-Group Classification Environment End-Products of Nature Direct Use Non-Use Direct User Structure / Types of Final ES Use Water • Extractive/ Consumptive Aquatic Flora Uses Industries Fauna • In-Situ (Non-Extractive/ Flows of Non-Consumptive) Uses Other Biotic Natural Final Terrestrial Material Households Ecosystem Atmospheric Components Services Soil Atmospheric Government Other Abiotic Natural Material Non-Use Composite End-Products • Existence Other End-Products • Bequest (Supply) (Demand) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors thank Jennifer Richkus, Jennifer Phelan, Robert Truesdale, Mary Barber, David Bellard, and others from RTI International for providing feedback and research support during the development of this report. The early leadership of former EPA employee John Powers proved instrumental in launching this effort. The authors thank Amanda Nahlik, Tony Olsen, Kevin Summers, Kathryn Saterson, Randy Bruins, Christine Davis, Bryan Hubbell, Julie Hewitt, Ashley Allen, Todd Doley, Karen Milam, David Simpson, and others at EPA for their discussion and feedback on earlier versions of this document. In addition, the authors thank V. Kerry Smith, Neville D. Crossman, and Brendan Fisher for review comments. Finally, the authors would like to thank participants of the two NESCS Workshops held in 2012 and 2013, as well as participants of an ACES session in 2014. Any factual or attribution errors are the responsibility of the authors alone. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION This document was developed under U.S. EPA Contract EP-W-11-029 with RTI International (Paramita Sinha and George Van Houtven), in collaboration with the ORISE Participant Program between U.S. -

Geodiversity of the South Coast Region, New South Wales

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine & Health - Honours Theses University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2012 Geodiversity of the South Coast Region, New South Wales Michelle Grierson University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/thsci University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Grierson, Michelle, Geodiversity of the South Coast Region, New South Wales, Bachelor of Environmental Science (Honours), School of Earth & Environmental Science, University of Wollongong, 2012. -

Granite Landscapes, Geodiversity and Geoheritage—Global Context

heritage Review Granite Landscapes, Geodiversity and Geoheritage—Global Context Piotr Migo ´n Institute of Geography and Regional Development, University of Wrocław, pl. Uniwersytecki 1, 50-137 Wrocław, Poland; [email protected] Abstract: Granite geomorphological sceneries are important components of global geoheritage, but international awareness of their significance seems insufficient. Based on existing literature, ten distinctive types of relief are identified, along with several sub-types, and an overview of medium-size and minor landforms characteristic for granite terrains is provided. Collectively, they tell stories about landscape evolution and environmental changes over geological timescale, having also considerable aesthetic values in many cases. Nevertheless, representation of granite landscapes and landforms on the UNESCO World Heritage List and within the UNESCO Global Geopark network is relatively scarce and only a few properties have been awarded World Heritage status in recognition of their scientific value or unique scenery. Much more often, reasons for inscription resided elsewhere, in biodiversity or cultural heritage values, despite very high geomorphological significance. To facilitate future global comparative analysis a framework is proposed that can be used for this purpose. Keywords: geoheritage; geodiversity; granite landforms; landform classification; World Heritage 1. Introduction Geoheritage is variously defined in scholarly literature, but notwithstanding rather subtle differences there is a general agreement that is refers to elements of the Earth’s geo- Citation: Migo´n,P. Granite diversity that are considered to have significant scientific, educational, cultural or aesthetic Landscapes, Geodiversity and value and are therefore subject to conservation and management [1,2]. Geodiversity, in Geoheritage—Global Context. turn, means the natural range of geological (rocks, minerals, fossils), geomorphological Heritage 2021 4 , , 198–219. -

Strategic Environmental Assessment Biodiversity and Geodiversity Considerations in Strategic Environmental Assessment

Scottish Natural Heritage Biodiversity and Geodiversity Considerations in Strategic Environmental Assessment Biodiversity and Geodiversity Considerations in Strategic Environmental Assessment Contents Paragraph Number Purpose 1 - 2 Background Definition 3 - 6 Why are these important? 7 - 9 Biodiversity, Geodiversity and the SEA process 10 - 15 How Your Plans Can Affect Biodiversity and Geodiversity 16 - 18 Likely land use changes by plan topic Table 1 At the Outset - Screening Likely significant effect on the environment – biodiversity and geodiversity 19 - 22 Screening Checklist Table 2 Initial Preparation - Scoping What to think about at Scoping stage 23 - 24 Environmental baseline 25, Table 3 Other relevant plans and programmes which set the context for biodiversity and geodiversity in your plan 26 - 27 Defining Objectives/outcomes and Indicators/checklists 28 - 30, Table 4 Assessing the Effects Assessing effects on biodiversity and geodiversity 31 - 33, Table 5 Assessing options and reasonable alternatives 34 - 37 Assessing the Aims, policies and proposals of your plan 38 - 40, Fig 1, Table 5 Reporting significance of effects 41 Mitigation 42 - 45, Table 7 Monitoring 46 - 49, Table 8 List of Acronyms Table 9 Annex 1 The Biodiversity and Geodiversity Resource Where Biodiversity and Geodiversity Fit with other SEA Topics Annex 2 Biodiversity and Geodiversity Related Plans and Strategies Annex 3 The Ecosystem Approach and where biodiversity and geodiversity fit in. Purpose 1. This guidance deals with considerations of biodiversity and geodiversity in the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) process. It defines biodiversity and geodiversity, looks at how plans can affect these elements, and details the key relevant stages of the SEA process. 2. -

Iucn Definitions English-French

Updated: 03 May 2021 A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z *A* Abatement. Abatement is the word which is used to denote the result of decreased Greenhouse Gases Emission. This can also be taken as an activity to lessen the effects of Greenhouse Effect. Abiotic (factors). Non-biological (as opposed to biotic), e.g. salinity, currents, light etc. Aboveground biomass. All living biomass above the soil including the stem, stump, branches, bark, seeds and foliage is known as aboveground biomass. Absolute Humidity. The quantity of water vapour in a given volume of air expressed by mass is known as absolute humidity. Absolute Risk. A quantitative or qualitative prediction of the likelihood and significance of a given impact is known as absolute risk. In the Voluntary Carbon Standard (VCS), the level of absolute risk can be calculated using the ‘likelihood × significance’ methodology. The calculated risk can then be converted into a risk classification. Abyss. The sunless deep sea bottom, ocean basins or abyssal plain descending from 2,000m to about 6,000m. Abyssal plain. The extensive, flat, gently sloping or nearly level region of the ocean floor from about 2,000m to 6,000m depth; the upper abyssal plain (2,000–4,000m) is also often referred to as the continental rise. Acceptable risk. The level of potential losses that a society or community considers acceptable given existing social, economic, political, cultural, technical and environmental conditions is known as acceptable risk. It describes the likelihood of an event whose probability of occurrence is small, whose consequences are so slight, or whose benefits (perceived or real) are so great, that individuals or groups in society are willing to take or be subjected to the risk that the event might occur. -

Conference Program and Abstracts

International Biogeography Society 7th Biennial Meeting ǀ 8–12 January 2015, Bayreuth, Germany Conference Program and Abstracts published as frontiers of biogeography vol. 6, suppl. 1 - december 2014 (ISSN 1948-6596 ) Conference Program and Abstracts International Biogeography Society 7th Biennial Meeting 8–12 January 2015, Bayreuth, Germany Published in December 2014 as supplement 1 of volume 6 of frontiers of biogeography (ISSN 1948-6596). Suggested citations: Gavin, D., Beierkuhnlein, C., Holzheu, S., Thies, B., Faller, K., Gillespie, R. & Hortal, J., eds. (2014) Conference program and abstracts. International Biogeography Society 7th Bien- nial Meeting. 8—2 January 2015, Bayreuth, Germany. Frontiers of Biogeography Vol. 6, suppl. 1. International Biogeography Society, 246 pp . Rabosky, D. (2014) MacArthur & Wilson Award Lecture: Speciation, extinction, and the geo- graphy of species richness In Conference program and abstracts. International Biogeo- graphy Society 7th Biennial Meeting. 8–12 January 2015, Bayreuth, Germany. (ed. by D. Gavin, C. Beierkuhnlein, S. Holzheu, B. Thies, K. Faller, R. Gillespie & J. Hortal), Frontiers of Biogeography Vol. 6, suppl. 1, p. 8. International Biogeography Society. This abstract book is available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/fb and the IBS website: http://www.biogeography.org/html/fb.html Passing for press on December 14th. General index General information 1 Conference Timetable 7 Plenary Lectures 9 Plenary Symposia 13 PS1: Adaptation, migration, persistence, extinction: New insights from -

Isle of Wight Geodiversity Action Plan

Isle of Wight Local Geodiversity Action Plan (LGAP) Isle of Wight Local Geodiversity Action Plan (IWLGAP) Geodiversity (geological diversity) is the variety of earth materials, forms and processes that constitute either the whole Earth or a specific region of it. The sequence of early Cretaceous Wealden rocks at Barnes High. Sedimentation by rivers, lakes and river deltas can all be seen at this one site. February 2010 (First Draft [2005] produced for: English Nature contract no. EIT34-04-024) 1st online issue February 2010 Page 1 of 87 Isle of Wight Local Geodiversity Action Plan (LGAP) ‘The primary function of the Isle of Wight Local Geodiversity Action Plan is to formulate a strategy to promote the Isle of Wight through the conservation and sustainable development of its Earth Heritage.’ Geodiversity (geological diversity) is the variety of earth materials, forms and processes that constitute either the whole Earth or a specific region of it. Relevant materials include minerals, rocks, sediments, fossils, and soils. Forms may comprise of folds, faults, landforms and other expressions of morphology or relations between units of earth material. Any natural process that continues to act upon, maintain or modify either material or form (for example tectonics, sediment transport, pedogenesis) represents another aspect of geodiversity. However geodiversity is not normally defined to include the likes of landscaping, concrete or other significant human influence. Gray, M. 2004. Geodiversity: Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester. 1st online issue February 2010 Page 2 of 87 Isle of Wight Local Geodiversity Action Plan (LGAP) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Much of what we do is heavily influenced by the underlying geology; from where we build, grow crops, collect water and where we carry out our recreational activities. -

Linking Geoconservation with Biodiversity Conservation in Protected Areas

International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks 7 (2019) 211–217 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks journal homepage: http://www.keaipublishing.com/en/journals/ international-journal-of-geoheritage-and-parks/ Linking geoconservation with biodiversity conservation in protected areas Roger Crofts IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas, Geoheritage Specialist Group, 6 Eskside West, Musselburgh, Scotland EH21 6HZ, UK article info Article history: This article explores the interaction between conservation of biodiversity and geodiversity in Received 6 October 2019 protectedareas.Itreflects the guidance booklet being developed by the IUCN World Commis- Received in revised form 3 December 2019 sion on Protected Areas Geoheritage Specialist Group led by the author. The paper explores the Accepted 15 December 2019 reasons why conservation of biodiversity and geodiversity in protected areas are often consid- Available online 26 December 2019 ered separately in international systems and processes, in training of staff and in action on the ground. It argues the need for a more integrated and interconnected approach recognising the Keywords: interdependencies of the two elements and especially the dependency of biological features Geoconservation; and processes on geological and geomorphological systems and processes. Examples of inte- Biodiversity conservation; grated approaches and separate approaches are discussed. The framework for resolution of Integrated approaches; conflict of ecosystem functions is presented. Finally, the practicalities of dealing with the con- Protected areas; fl Conflict resolution icts between the two elements are discussed. © 2019 Beijing Normal University. Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). -

Characterising Scotland's Marine Environment to Define Search Locations for New Marine Protected Areas

Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 432 Characterising Scotland's marine environment to define search locations for new Marine Protected Areas Part 2: The identification of key geodiversity areas in Scottish waters COMMISSIONED REPORT Commissioned Report No. 432 Characterising Scotland's marine environment to define search locations for new Marine Protected Areas Part 2: The identification of key geodiversity areas in Scottish waters For further information on this report please contact: Ben James Scottish Natural Heritage Great Glen House Leachkin Road INVERNESS IV3 8NW Telephone: 01463 725235 E-mail: [email protected] This report should be quoted as: Brooks, A.J. Kenyon, N.H. Leslie, A., Long, D. & Gordon, J.E. 2013. Characterising Scotland's marine environment to define search locations for new Marine Protected Areas. Part 2: The identification of key geodiversity areas in Scottish waters. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 432. This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the author(s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Natural Heritage 2013. COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary The identification of key geodiversity areas in Scottish waters Commissioned Report No. 432 Project no: 28877 Contractor: ABP Marine Environmental Research Ltd Year of publication: 2013 Background The Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 and the UK Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 include new powers for Scottish Ministers to designate Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the seas around Scotland as part of a range of measures to manage and protect Scotland’s seas for current and future generations. -

Cultural Ecosystem Services of Geodiversity: a Case Study from Stránská Skála (Brno, Czech Republic)

land Article Cultural Ecosystem Services of Geodiversity: A Case Study from Stránská skála (Brno, Czech Republic) Lucie Kubalíková Department of Geology and Pedology, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology, Mendel University in Brno, Zemˇedˇelská 3, 613 00 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] Received: 12 March 2020; Accepted: 28 March 2020; Published: 31 March 2020 Abstract: The concept of ecosystem services developed in the second half of the 20th century, and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment was crucial for its acceptance. This assessment identified the services that ecosystems provide to society, but geodiversity (as an indispensable component of ecosystems) was somewhat underestimated. At present, geodiversity is intensively used by human society and it provides numerous services including cultural as a resource for tourism, recreation, as a part of natural heritage, and to satisfy matters of spiritual importance. The main purpose of this paper is to present the geocultural issues of Stránská skála (a limestone cliff with caves and an anthropogenic underground) in Brno (Czech Republic) and to evaluate the cultural ecosystem services of geodiversity by using the abiotic ecosystem services approach. This assessment of cultural ecosystem services of the Stránská skála enables the identification and description of the functions and services which are provided by geodiversity and confirms the high cultural and geoheritage value of the site. Keywords: abiotic ecosystem services; geocultural site; geoconservation; geoheritage; geotourism 1. Introduction Geodiversity (of an abiotic or inanimate nature) is defined as the natural range (diversity) of geological (rocks, minerals, fossils), geomorphological (landforms, topography, physical processes), soil, and hydrological features including their assemblages, structures, systems, and contribution to landscapes [1,2].