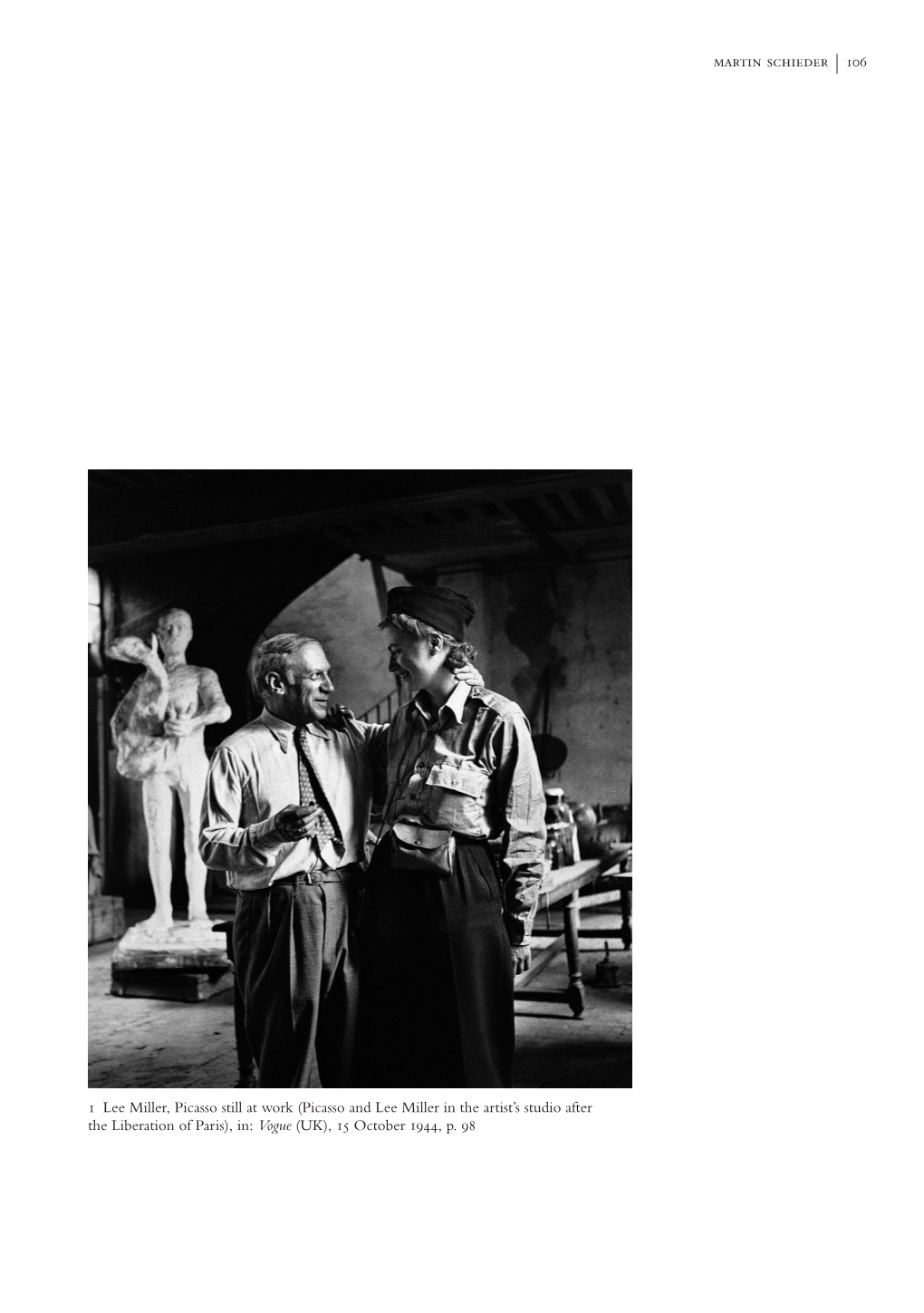

Picasso Libre *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Project of Liberation and the Projection of National Identity. Calvo, Aragon, Jouhandeau, 1944-1945 by Aparna Nayak-Guercio

The project of Liberation and the projection of national identity. Calvo, Aragon, Jouhandeau, 1944-1945 by Aparna Nayak-Guercio B.A. University of Bombay, India, 1990 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 1993 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Aparna Nayak-Guercio It was defended on December 13, 2005 and approved by Dr. Alexander Orbach, Associate Professor, Department of Religious Studies Dr. Giuseppina Mecchia, Assistant Professor, Department of French and Italian Dr. Lina Insana, Assistant Professor, Department of French and Italian Dr. Roberta Hatcher, Assistant Professor, Department of French and Italian Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Philip Watts, Assistant Professor, Department of French and Italian ii Copyright © by Aparna Nayak-Guercio 2006 iii THE PROJECT OF LIBERATION AND THE PROJECTION OF NATIONAL IDENTITY. ARAGON, CALVO, JOUHANDEAU, 1944-45 Aparna Nayak-Guercio, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 This dissertation focuses on the months of liberation of France, June 1944 to May 1945. It analyzes three under-studied works taken as samples of texts that touch upon the question of contested identities. The texts are chosen from the main divisions of the political spectrum, namely Gaullist, far right, and far left. Although the focus is on the texts themselves, I trace the arguments found in these works to the larger discourses in which they are inscribed. In particular, I address the questions of guilt and innocence, justice and vengeance, past and future in the given historical circumstances. -

Amrita Sher-Gil—The European Connection

Amrita Sher-Gil—The European connection This talk was proposed in a very sponteanous manner when Geza, who had been asking me to do an exhibition, said that he was leaving shortly. As with the Sher-Gil archive exhibition held here some years ago, the approach would be using archival material, go through the biography and finally suggest some other ways of looking at the subject. The talk was to be mainly spoken, interlaced with quotations. Now there will be telegraphic information in place of the verbal. In other words an a hugely incomplete presentation, compensated by a large number of visuals. I hope you will bear with us. 1&2: Umrao Singh and his younger brother, Sunder Singh taken in 1889, most probably by Umrao Singh himself. Striking a pose, being unconventional, Umrao Singh looks out, while his brother places his bat firmly on the ground—the latter will be knighted, will start one of Asia’s largest sugar factory in Gorakhpur ( where Amrita will spend the last years of her life ). Umrao will use his camera with a personal passion and take self portraits for almost sixty years as well as photograph his new family. Umrao Singh went to London in 1896 for a year and would certainly have met Princess Bamba, the daughter of Raja Dalip Singh, and Grand daughter of Raja Ranjit Singh. 3& 4: In October 1910 she came to Lahore with a young Hungarian, who was her travelling companion. On new years eve Umrao Singh wrote in Marie Antionette dairy a poem of Kalidasa and a friend, an Urdu poet wrote in the same book on 15 January 1911, the following poem translated by Umrao Singh. -

2006 Annual Conference Program Sessions

24 CAA Conference Information 2006 ARTspace is a conference within the Conference, tailored to the interests and needs of practicing artists, but open to all. It includes a large audience session space and a section devoted to the video lounge. UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED. ALL ARTSPACE EVENTS ARE IN THE HYNES CONVENTION GENTER, THIRD LEVEl, ROOM 312. WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 22 ------------------- 7:30 AM-9:00 AM MORNING COFFEE, TEA, AND JUICE 9:30 AM-NOON SlOPART.COM BRIAN REEVES AND ADRIANE HERMAN Slop Art corporate representatives will share popular new product distribution and expression-formatting strategies they've developed to address mounting consumer expectation for increasing affordability, portability, familiar formatting, and validating brand recognition. New franchise opportunities, including the Slop Brand Shippable Showroom™, will be outlined. Certified Masterworks™ and product submission guidelines FREE to all attendees. 12:30 PM-2:00 PM RECENT WORK FROM THE MIT MEDIA LAB Christopher Csikszelltlnihalyi, a visual artist on the faculty at the MIT Media Lab, coordinates a presentation featuring recent faculty work from the MIT Media Lab; see http;llwww.media.mit.edu/about! academics.htm!. 2:30 PM-5:00 PM STUDIO ART OPEN SESSIOII PAINTING Chairs; Alfredo Gisholl, Brandeis University; John G. Walker, Boston University Panelists to be announced. BOSTON 25 THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 23 2:30 PM-5:00 PM STUDIO ART OPEN SESSIOII 7:30 AM-9:00 AM PRINTERLY PAINTERLY: THE INTERRELATIONSHIP OF PAINTING AND PRINTMAKING MORNING COFFEE, TEA, AND JUICE Chair: Nona Hershey, Massachusetts College of Art Clillord Ackley, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 9:00 AM-5:30 PM Michael Mazur, independent artist James Stroud, independent artist, Center Street Studio, Milton Village, VIDEO lOUNGE: EXPANDED CINEMA FOR THE DIGITAL AGE Massachusetts A video screening curated by leslie Raymond and Antony Flackett Expanded Cinema emerged in the 19605 with aspirations to explore expanded consciousness through the technology of the moving image. -

Identity and Positioning in Algerian and Franco-Algerian Contemporary Art

Identity and Positioning in Algerian and Franco-Algerian Contemporary Art Martin Elms A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of French Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of Languages and Cultures The University of Sheffield 13 December 2019 1 Abstract Identity and belonging increasingly feature as themes in the work of contemporary artists, a focus that seems particularly felt by those artists who either personally or through their families have experienced dispersal and migration. The thesis explores how fourteen Algerian and Franco-Algerian artists position themselves and are positioned by others to identity and community. The difficult intertwined histories of Algeria and France fraught with the consequences of colonisation, the impact of migration, and, in Algeria, civil war, provides a rich terrain for the exploration of identity formation. Positionality theory is used to analyse the process of identity formation in the artists and how this developed over the course of their careers and in their art. An important part of the analysis is concerned with how the artists positioned themselves consciously or inadvertently to fixed or fluid conceptions of identity and how this was reflected in their artworks. The thesis examines the complex politics of identity and belonging that extends beyond nationality and diaspora and implicates a range of other identifications including that of class, ethnicity, gender, sexuality and career choice. The research addresses a gap in contemporary art scholarship by targeting a specific group of artists and their work and examining how they negotiate, in an increasingly globalised world, their relationship to identity including nationality and diaspora. -

Historical Dictionary of World War II France Historical Dictionaries of French History

Historical Dictionary of World War II France Historical Dictionaries of French History Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution, 1789–1799 Samuel F. Scott and Barry Rothaus, editors Historical Dictionary of Napoleonic France, 1799–1815 Owen Connelly, editor Historical Dictionary of France from the 1815 Restoration to the Second Empire Edgar Leon Newman, editor Historical Dictionary of the French Second Empire, 1852–1870 William E. Echard, editor Historical Dictionary of the Third French Republic, 1870–1940 Patrick H. Hutton, editor-in-chief Historical Dictionary of the French Fourth and Fifth Republics, 1946–1991 Wayne Northcutt, editor-in-chief Historical Dictionary of World War II France The Occupation, Vichy, and the Resistance, 1938–1946 Edited by BERTRAM M. GORDON Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Historical dictionary of World War II France : the Occupation, Vichy, and the Resistance, 1938–1946 / edited by Bertram M. Gordon. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–29421–6 (alk. paper) 1. France—History—German occupation, 1940–1945—Dictionaries. 2. World War, 1939–1945—Underground movements—France— Dictionaries. 3. World War, 1939–1945—France—Colonies— Dictionaries. I. Gordon, Bertram M., 1943– . DC397.H58 1998 940.53'44—dc21 97–18190 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright ᭧ 1998 by Bertram M. Gordon All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 97–18190 ISBN: 0–313–29421–6 First published in 1998 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. -

Nuestra Memoria

Nuestra Memoria Año XIII · Nº 28 · Abril de 2007 El Museo del Holocausto de Buenos Aires es miembro de la delegación argentina de la ITF* *ITF: Task Force for International Cooperation in Holocaust Education, Remembrance, and Research. Grupo de Trabajo para la Cooperación Internacional en Educación, Rememoración e Investigación del Holocausto. 2 / Nuestra Memoria Nuestra Memoria Consejo de Administración 2005/2007 Año XIII, Nº 28, abril de 2007 Presidente Dr. Mario Feferbaum CONSEJO EDITORIAL Vicepresidentes Dr. Alejandro Dosoretz Arq. Boris Kalnicki Coordinación general Dr. José Menascé Lic. Sima Weingarten Dr. Enrique Ovsejevich Sra. Susana Rochwerger Asesor Secretaria General Lic. Sima Weingarten Prof. Abraham Zylberman Prosecretarios Sr. Daniel Banet Colaboradores Lic. Mario Silberstein Julia Juhasz Tesorero Dr. Manuel Kobryniec Dr. José Menascé Protesoreros Sr. Jaime Machabanski Miriam Scheinberg Dr. Sixto Stolovitzky Nejama Schneid Bruria Sorgen Vocales Sr. Moisés Borowicz Sra. Raquel Dawidowicz Consejo Académico Sr. Enrique Dychter Dra. Graciela Ben Dror Sr. Gregorio Fridman Dr. Yossi Goldstein Dr. Pablo Goldman Prof. Avraham Milgram Sra. Danuta Gotlieb Dr. Daniel Rafecas Sr. León Grzmot Dr. Leonardo Senkman Lic. Susana Luterstein Sra. Eva Rosenthal Producción Dr. César Siculer z’l Lic. Claudio Gustavo Goldman Sra. Eugenia Unger Lic. Susana Zang Diseño e impresión Marcelo Kohan Vocales Suplentes Lic. Tobías Holc Dr. Norberto Selinger z’l Sr. Ernesto Slelatt Revisor de Cuentas Sr. Israel L. Nielavitzky Presidente Fundador Dr. Gilbert Lewi z’l “Nuestra Memoria” es una publica- ción de la Fundación Memoria del Ho- Directora Ejecutiva Prof. Graciela N. de Jinich locausto. Las colaboraciones firmadas Comité de Honor Arq. Ralph Appelbaum expresan la opinión de sus autores, Prof. -

Cent-Onze Dessins Faits À Buchenwald

1 Cent-onze dessins faits à Buchenwald BORIS TASLITZKY Cent-onze dessins faits à Buchenwald Association française Buchenwald-Dora Editions Hautefeuille (Ç) 1978 TousAssociation droits defrançaise reproduction Buchenwald-Dora réservés pour - tousHautefeuille pays. S.A. AVANT-PROPOS par Marcel Paul Les dessins de Boris Taslitzky n'ont pas à être présentés, ils sont, dans l'absolu, l'expression tellement bien connue de la sensibilité infinie de leur auteur. L'on retrouve dans ces dessins à la fois l'élan, la révolte du cœur, du grand artiste ; le courage du lutteur qui s'est jeté dans la mêlée, corps et âme, et en pleine connaissance des risques. Et cela dès les premières heures tragi- ques où pour l'humanité humiliée, bafouée, tout semblait perdu. Ces dessins ont été réalisés à Buchenwald dans l'enfer de la faim, du froid, de la violence et au-delà de la violence : de la cruauté et de la mort ; ils sont en eux-mêmes d'une puissance pathétique,que personne n'a la possibilité de traduire en mots écrits ou paroles. J'ai lu avec respect, avec émotion, l'admirable préface de Julien Cain, l'un des grands parmi les plus grands de nos Universitaires. Julien Cain a rencontré Boris Tastlitzky à l'automne 1944, dans les "lieux d'aisance collectifs" d'un des blocs du bagne hitlérien qui portait le nom de "Buchenwald". Je ne puis dominer le désir de dire quelques mots de cette rencontre dans l'enceinte de la mort qu'était ce Buchenwald: plus de 15.000 m2 cerclés d'une double ronce de barbelés entrelacés, chargés d'électricité ; de barbelés sur- montés de miradors à angles de tirs de mitrailleuses minutieusement réglés vivantpour permettre dans l'enclos en quelquesmaudit. -

Tate Report 2002–2004

TATE REPORT 2002–2004 Tate Report 2002–2004 Introduction 1 Collection 6 Galleries & Online 227 Exhibitions 245 Learning 291 Business & Funding 295 Publishing & Research 309 People 359 TATE REPORT 2002–2004 1 Introduction Trustees’ Foreword 2 Director’s Introduction 4 TATE REPORT 2002–2004 2 Trustees’ Foreword • Following the opening of Tate Modern and Tate Britain in 2000, Tate has consolidated and built on this unique achieve- ment, presenting the Collection and exhibitions to large and new audiences. As well as adjusting to unprecedented change, we continue to develop and innovate, as a group of four gal- leries linked together within a single organisation. • One exciting area of growth has been Tate Online – tate.org.uk. Now the UK’s most popular art website, it has won two BAFTAs for online content and for innovation over the last two years. In a move that reflects this development, the full Tate Biennial Report is this year published online at tate.org.uk/tatereport. This printed publication presents a summary of a remarkable two years. • A highlight of the last biennium was the launch of the new Tate Boat in May 2003. Shuttling visitors along the Thames between Tate Britain and Tate Modern, it is a reminder of how important connections have been in defining Tate’s success. • Tate is a British institution with an international outlook, and two appointments from Europe – of Vicente Todolí as Director of Tate Modern in April 2003 and of Jan Debbaut as Director of Collection in September 2003 – are enabling us to develop our links abroad, bringing fresh perspectives to our programme. -

PRESS KIT Exhibition 05 April > 28 July 2019 the Exhibition Is Organised by the Musée De L’Armée and Musée National Picasso-Paris 2

1 PRESS KIT Exhibition 05 April > 28 July 2019 The exhibition is organised by the Musée de l’Armée and Musée National Picasso-Paris 2 1- Georges Braque (1882–1963), Portrait of Picasso Wearing Braque’s Uniform, Paris, 1911, Paris, Musée National Picasso-Paris CONTENTS PRESS RELEASE ............................................ P. 4 EXHIBITION CURATORS, SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE AND LENDERS ..... P. 5 EXHIBITION VISIT .....................................P.6-17 3 CLOSE-UPS .............................................P.18-19 AROUND THE EXHIBITION .....................P.20-23 CATALOGUE ............................................P.24-25 EXHIBITION PARTNERS .........................P.26-27 VISUALS FOR THE PRESS ......................P.28-29 PRACTICAL INFORMATION ......................... P.30 2- Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Caparisoned Horse and Knight in Armour, 24 January 1951, Paris, Musée National Picasso-Paris, Pablo Picasso donation through Acceptance in Lieu, 1979 PRESS RELEASE Picasso’s entire life (1881–1973) was marked by major conflicts, from the Cuban War of Independence to the Vietnam War, which came to an end two years after his death. The exhibition, organised by the Musée de l’Armée and the Musée National Picasso-Paris, takes a brand-new look at the various ways that warfare informed and impacted Picasso’s creative output throughout his career. The life of the Spanish artist, a The outbreak of the Second World statement. French and foreign loans French resident from 1901 until War followed by the Occupation enhance the exhibition’s approach his death in 1973, was punctuated put the artist in an extremely and bring a fresh perspective on by armed conflicts, although precarious position. During the subject. paradoxically he did not take an this period, marked by major active part in any war himself, upheavals, modern art, particularly The exhibition is organized and never served as a soldier. -

Art in Extremis: Creative Resistance During the Holocaust Dr

Art in Extremis: Creative Resistance during the Holocaust Dr. Rachel Perry Wednesdays 18:00-21:00, Fall Semester Office Hours: By appointment. Email: [email protected] Course Description: This course surveys art produced in extremis during the Holocaust, by individuals in hiding, or in the camps and ghettos. Together, we will explore how victims used artistic expression as both a means of documentation and as a form of “creative resistance” to communicate their protest, despair or hope. Course readings couple secondary literature with primary sources and ego documents of the period, such as the artists’ own writings and diaries. Particular attention will be given to the social, political and cultural contexts of art production and reception. Throughout, we will examine the complex and varied responses artists had to their circumstances. What rhetorical or stylistic strategies did artists employ (satire, irony, etc.)? What themes and motifs did they gravitate towards? What genres (portraiture, still life, landscape) predominate and why? How is gender represented and how did gender impact art making? What is the relationship between aesthetics and atrocity? Our material ranges from now iconic works such as Charlotte Salomon’s Life? Or Theater? to unfamiliar works by little known or even anonymous artists; from “high” art to popular culture; and from the fine arts (sculpture, prints, painting) to visual culture more broadly defined, as evidenced in comic books, satirical cartoons, posters, illustrated stamps, board games (like the Monopoly board from Terezin), carved tools, jewelry, clothing, wall decorations as well as the graffiti left on the walls of the camps. Instead of writing a final paper, students will be curating their own digital art exhibition. -

6Amrita Sher-Gil and Boris Taslitzky Or Who Is The

6Amrita Sher-Gil and Boris Taslitzky Or Who is the “Young Man with Apples” by Amrita Sher-Gil by Vivan Sundaram “It became quite different when she started painting, and when the transposition of the model was born on her canvas….It was neither classical, nor romantic nor contemporary, something belonging neither to yesterday nor today, it belonged to all epochs and to the present, a sort of present that anticipates the future.” Boris Taslitzky FN. 1. The model of Amrita Sher-Gil’s painting, Young Man with Apples, in the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi is the same person in her painting Man in White: his name is Boris Taslitzky, as another portrait that bears this name. Amrita painted the latter two portraits in 1930 soon after she joined the studio of Lucian Simon at the Ecole des Beaux- Arts in October 1929 when she was sixteen years old. She had come to Paris with her parents and sister in February and immediately was enrolled in the Grande- Chaumiere, the most famous Academy in Paris in the twenties under Pierre Valliant . ( Giacometti had studied there for five years until 1927, under Antoine Bordelle, who died in 1929) . In March 1929 Taslitzky joined the studio of Lucian Simon ( 1861-1945 ), a realist painter, whose style subsequently shifted towards post-impressionism. The handsome student, two years older than Amrita was on the look out for adventure, for a romance, an ‘orientalist’ attraction was in the making even before they met. FN-2 Painting each other’s portraits was the order of the day. -

The Genocide and Persecution of Roma and Sinti. Bibliography and Historiographical Review Ilsen About & Anna Abakunova

International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance The Genocide and Persecution of Roma and Sinti. Bibliography and Historiographical Review Ilsen About & Anna Abakunova O C A U H O L S T L E A C N O N I T A A I N R L E T L N I A R E E M C E M B R A N March 2016 About the IHRA The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) is an intergovernmental body whose purpose is to place political and social leaders’ support behind the need for Holocaust education, remembrance and research both nationally and internationally. IHRA (formerly the Task Force for International Cooperation on Holocaust Education, Remembrance and Research, or ITF) was initiated in 1998 by former Swedish Prime Minister Göran Persson. Persson decided to establish an international organization that would expand Holocaust education worldwide, and asked then President Bill Clinton and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair to join him in this effort. Persson also developed the idea of an international forum of governments interested in discussing Holocaust edu- cation, which took place in Stockholm between 27-29 January 2000. The Forum was attended by the repre- sentatives of 46 governments including; 23 Heads of State or Prime Ministers and 14 Deputy Prime Ministers or Ministers. The Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust was the outcome of the Forum’s deliberations and is the foundation of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. IHRA currently has 31 member countries, ten observer countries and seven Permanent International Partners. Members must be committed to the Stockholm Declaration and to the implementation of national policies and programs in support of Holocaust education, remembrance, and research.