Parathyroid Hormone, Phosphorus, Calcium, and Magnesium Testing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Blood Group Serology and Molecular Genetics Volume 34, Number 1, 2018 CONTENTS

Journal of Blood Group Serology and Molecular Genetics VOLUME 34, N UMBER 1, 2018 This issue of Immunohematology is supported by a contribution from Grifols Diagnostics Solutions, Inc. Dedicated to advancement and education in molecular and serologic immunohematology Immunohematology Journal of Blood Group Serology and Molecular Genetics Volume 34, Number 1, 2018 CONTENTS S EROLOGIC M ETHOD R EVIEW 1 Warm autoadsorption using ZZAP F.M. Tsimba-Chitsva, A. Caballero, and B. Svatora R EVIEW 4 Proceedings from the International Society of Blood Transfusion Working Party on Immunohaematology Workshop on the Clinical Significance of Red Blood Cell Alloantibodies, Friday, September 2, 2016, Dubai A brief overview of clinical significance of blood group antibodies M.J. Gandhi, D.M. Strong, B.I. Whitaker, and E. Petrisli C A S E R EPORT 7 Management of pregnancy sensitized with anti-Inb with monocyte monolayer assay and maternal blood donation R. Shree, K.K. Ma, L.S. Er and M. Delaney R EVIEW 11 Proceedings from the International Society of Blood Transfusion Working Party on Immunohaematology Workshop on the Clinical Significance of Red Blood Cell Alloantibodies, Friday, September 2, 2016, Dubai A review of in vitro methods to predict the clinical significance of red blood cell alloantibodies S.J. Nance S EROLOGIC M ETHOD R EVIEW 16 Recovery of autologous sickle cells by hypotonic wash E. Wilson, K. Kezeor, and M. Crosby TO THE E DITOR 19 The devil is in the details: retention of recipient group A type 5 years after a successful allogeneic bone marrow transplant from a group O donor L.L.W. -

Comparison of Histopathology, Immunofluorescence, and Serology

Global Dermatology Cae Report ISSN: 2056-7863 Comparison of histopathology, immunofluorescence, and serology for the diagnosis of autoimmune bullous disorders: an update Seline Ali E1, Seline Lauren N1, Sokumbi Olayemi1* and Motaparthi Kiran2,3 1Department of Dermatology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA 2Dermatopathology, Miraca Life Sciences, USA 3Department of Dermatology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA Introduction In an ELISA, the target antigen of interest (such as the NC16a domain of BP180) is immobilized by physical adsorption or by The diagnosis of autoimmune bullous disorders (AIBDs) relies on antibody capture. When antibody capture is utilized, this is referred to several different diagnostic methods. These include histopathology, as “sandwich ELISA” because the target antigen is bound between the direct immunofluorescence (DIF), indirect immunofluorescence immobilizing antibody and the primary antibody. Primary antibodies (IIF), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and are present in the patient’s serum. Enzyme-linked secondary antibodies immunoblotting. When faced with a presumptive AIBD, the are then added which bind the Fc region of primary antibodies. most widely employed method for diagnosis by dermatologists is Substrate is added and converted by the enzyme into a signal. A a combination of histopathology and DIF. While DIF is still the resulting color change, fluorescence, or electrochemical signal is diagnostic method of choice for linear IgA bullous disease and IgA quantitatively measured and reported [5]. pemphigus, ELISA is a more accurate, cost-effective and less invasive method of diagnosis for several AIBDs including pemphigus vulgaris Western blot is synonymous with immunoblot. For this method, and foliaceus, based on currently available evidence [1-3]. -

Online-Only Appendix: List of Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

ONLINE-ONLY APPENDIX: LIST OF INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA INCLUSION CRITERIA [1] Male subjects between the ages of 35 and 70 years, inclusive, with Type 2 diabetes mellitus as defined by the American Diabetes Association (Diabetes care, Vol. 21: S5- S19, 1998) for more than one year. [2] Subjects must have Body Mass Index (BMI) < 36 kg/m². [3] Stable glycemic control (Hb A1C <11%). [4] Subjects must be off all oral hypoglycemic agents 24 hours prior to each study dosing day and off any investigational drug for at least four weeks. [5] Subjects must refrain from strenuous physical activity beginning 72 hours prior to admission and through the duration of the study. [6] Subjects must be willing and able to be confined to the Clinical Research Unit as required by the protocol. [7] Subjects must be willing and able to provide written informed consent. EXCLUSION CRITERIA [1] History or presence of clinically significant cardiovascular, respiratory, hepatic, renal, gastrointestinal, neurological or infectious disorders capable of altering the absorption, metabolism or elimination of drugs, or of constituting a risk factor when taking the study medication. [2] Subjects with gastroparesis, orthostatic hypotension and hypoglycemia unawareness (autonomic neuropathy). [3] Subjects with “brittle” diabetes or predisposition to severe hypoglycemia, e.g., 2 or more serious hypoglycemic episodes (requiring another’s assistance) within the past year, or any hospitalization or emergency room visit due to poor diabetic control within the past 6 months. [4] Evidence of significant active hematological disease and/or cumulative blood donation of 1 unit (500 mL) or more including blood drawn during clinical trials in the last 3 months. -

Application of Quantitative Immunofluorescence to Clinical Serology: Antibody Levels of Treponema Pallidum GRACE L

JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY, May 1992, p. 1294-1296 Vol. 30, No. 5 0095-1137/92/051294-03$02.00/0 Copyright C 1992, American Society for Microbiology Application of Quantitative Immunofluorescence to Clinical Serology: Antibody Levels of Treponema pallidum GRACE L. PICCIOLO* AND DAVID S. KAPLAN Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Food and Drug Administration, 12200 Wilkins Avenue, Rockville, Maryland 20852 Received 27 March 1991/Accepted 20 January 1992 A previously reported method of quantitative immunofluorescence, employing a calibrated photometric system and chemically stabilized fluorescence intensity, was used to replace the subjective, visual method of endpoint determination with a quantitative, calibrated measurement of antibodies to Treponema paUlidum in serum. The results of the quantitative immunofluorescence method showed a 90% correlation with the subjective determinations of the visual method. A quantitative immunofluorescence (QIF) method to de- measured by using an acridine orange filter set, with a 400- to termine immunofluorescence with a quantitative, calibrated 440-nm excitation and LP 470 emission filters. photometric intensity of the fluorescent reaction product has Reducing agent. Dithioerythritol (DTE) (Sigma Chemical been reported previously by us (4). This method used uranyl Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was prepared as stock solution contain- glass slides in the calibration and standardization of the ing 0.3 M reducing agent in 0.5 M Tris buffer, pH 8.2 (Sigma microscope-photometer voltage measurements. To stabilize Chemical Co.). DTE was diluted 1:9 with standard buffered the fluorescence emission, dithioerythritol (DTE) was incor- glycerol mounting medium (Clinical Sciences, Inc., Whip- porated into the buffered glycerol mounting medium of the pany, N.J.) (4, 8). -

Clinical Placements Serology Screening for Students

Gawler Place Medical Practice Level 1, Key Invest Building 49 Gawler Place Adelaide SA 5000 T: 08 8212 7175 F: 08 8212 1993 E: [email protected] www.adelaideunicare.com.au CLINICAL PLACEMENTS SEROLOGY SCREENING FOR STUDENTS Gawler Place Medical Practice have put together this Question and Answer sheet to assist you in meeting the requirements of SA Health’s Immunisation for Health Care Workers in South Australia Policy – August 2017. It is a requirement that all Health Care Workers have adequate immunisation against certain diseases prior to working in a clinical environment. What is Serology Screening and why do I need to do it? Serology Screening is a blood test that looks for antibodies in your blood. The purpose of such a test is to detect serum antibodies to prove protective immunity against a disease. Where can I have Serology Screening done? Gawler Place Medical Practice offer Serology Screening appointments to allow incoming students to have their serology screening completed, and where required, obtain their required vaccinations to meet SA Health’s Immunisation for Health Care Workers in South Australia – August 2017. Australian Clinical Labs are located within our Practice so that you can have your blood taken (if required) as soon as you have seen the doctor. How do I make an appointment? You may contact the practice to organise an appointment, our telephone number is 8212 7175 or make a booking online. Please make a long appointment booking. If you need to change or cancel an appointment please contact our Practice on (08) 2127175 as soon as possible so that your appointment can be offered to another person. -

Iron Deficiency Anemia: Evaluation and Management MATTHEW W

Iron Deficiency Anemia: Evaluation and Management MATTHEW W. SHORT, LTC, MC, USA, and JASON E. DOMAGALSKI, MAJ, MC, USA Madigan Healthcare System, Tacoma, Washington Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional disorder worldwide and accounts for approxi- mately one-half of anemia cases. The diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia is confirmed by the findings of low iron stores and a hemoglobin level two standard deviations below normal. Women should be screened during pregnancy, and children screened at one year of age. Supple- mental iron may be given initially, followed by further workup if the patient is not responsive to therapy. Men and postmenopausal women should not be screened, but should be evaluated with gastrointestinal endoscopy if diagnosed with iron deficiency anemia. The underlying cause should be treated, and oral iron therapy can be initiated to replenish iron stores. Paren- teral therapy may be used in patients who cannot tolerate or absorb oral preparations. (Am Fam Physician. 2013;87(2):98-104. Copyright © 2013 American Academy of Family Physicians.) ▲ Patient information: ron deficiency anemia is diminished red causes of microcytosis include chronic A handout on iron defi- blood cell production due to low iron inflammatory states, lead poisoning, thalas- ciency anemia, written by 1 the authors of this article, stores in the body. It is the most com- semia, and sideroblastic anemia. is available at http://www. mon nutritional disorder worldwide The following diagnostic approach is rec- aafp.org/afp/2013/0115/ I and accounts for approximately one-half of ommended in patients with anemia and is p98-s1.html. Access to anemia cases.1,2 Iron deficiency anemia can outlined in Figure 1.2,6-11 A serum ferritin level the handout is free and unrestricted. -

Sourcebook in Forensic Serology, Immunology, and Biochemistry

UNIT VII. HEMOGLOBIN, SERUM GROUP SYSTEMS, HLA AND OTHER GENETIC MARKERS Hemoglobin SECTION 38. HEMOGLOBIN 38.1 Introduction Hemoglobin (Hb)is the major protein of human red cells, forth. Hemoglobins exist which contain only one kind of comprising about 95% of their dry weight. Adult human chain: Hb H is B4, for example, and Hb Bart's is 7,. blood normally contains from about 4 million to 6.5 million Jones (1961) pointed out that hemoglobin structural red cells per mm3 blood, the average figure being slightly heterogeneity can be classified as follows: (1) Maturation higher for men. Hemoglobin itself is present in concentra- heterogeneity, which refers to the fact that different tions of about 14 to 16 g per 100 mP blood. It is the oxygen hemoglobins are normally synthesized during different transporting protein in higher animals; without a molecule stages of development. There are embryonic, fetal and adult having its properties, complex multicellular aerobic life as hemoglobins. (2) Minor hemoglobin heterogeneity, which we know it would not be possible. refers to the presence of small amounts of structurally dif- Hemoglobin is one of the most extensively studied of all ferent but normal hemoglobins along with the major proteins, and its literature fills many volumes. As noted in component characteristic of a particular stage of develop- section 5.1, it acquired its present name over 100 years ago ment; and (3) genetic heterogeneity, which refers to the (Hoppe-Seyler, 1864). In forensic serology, hemoglobiin is various "abnormal" hemoglobin variants. Many of these important in two principal contexts: (1) Blood is normally are thought to be the result of point mutations, and with a idenad in questioned samples by procedures designed to few exceptions, variant hemoglobins are very rare. -

COVID-19 Resources for Clinical Chemistry Laboratories

COVID-19 Resources for Clinical Chemistry Laboratories Last updated: 8 September 2020 The following is a list of resources related to the laboratory management of the COVID-19 outbreak. Jump to section • Resources from governing bodies • Personal safety and use of PPE • Disease transmission • Diagnostic testing • Clinical features and the role of laboratory testing • Paediatrics • Maternal medicine • Treatment for COVID-19 • Research This collection of resources reflects a rapidly changing situation. We have not critically appraised all resources cited here for scientific validity but tried to present information that is believed to help laboratory professionals in formulating their local policies in a better- informed manner. The interim advice or conclusions presented here may change as more information is gathered. If you wish to add a resource or have any other feedback, please get in touch via the contact details below: Dr Simon Thompson Chemical Pathology Registrar, NSW Health Pathology [email protected] Contents Resources from governing bodies ................................................................................. 3 Australian Government advice ....................................................................................... 3 NSW Health ................................................................................................................... 3 World Health Organisation ............................................................................................. 3 RCPA ............................................................................................................................ -

Interpreting Liver Function Tests CONTENTS

A CASE-BASED SERIES ON PRACTICAL PATHOLOGY FOR GPs FEBRUARY 2020 Interpreting liver function tests CONTENTS: • Dealing with abnormal LFTs in the asymptomatic patient • Diagnosing Gilbert’s syndrome © The Royal College of • Establishing the source of raised ALP Pathologists of Australasia 2 Authors: Dr Melissa Gillett Dr Rebecca Brereton MBBS, FRACP, FRCPA, MAACB Specialist Chemical Pathologist, Chemical Pathologist, Fiona Stanley Hospital Network Fiona Stanley Hospital Network Laboratory, PathWest Laboratory Laboratory, PathWest Laboratory Medicine, Murdoch, WA Medicine, Murdoch, WA Common Sense Pathology is developed by the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia and supported by Australian Doctor Group. © 2020 Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia www.rcpa.edu.au CEO: Dr Debra Graves Email: [email protected] While the views expressed are those of the authors, modified by expert reviewers, they are not necessarily held by the College. Published by Australian Doctor Group Level 2, 26-32 Pyrmont Bridge Road, Pyrmont NSW 2009 Ph: 1300 360 126 Email: [email protected] Website: www.australiandoctorgroup.com.au ACN: 615 959 914 ABN: 94 615 959 914 ISSN: 1039-7116 The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of Australian Doctor Group. This issue is produced and owned by the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia and distributed by Australian Doctor Group. Common Sense Pathology Editor: Dr Steve Flecknoe-Brown Email: [email protected] Editor: Dr Karley Heyworth Email: [email protected] Sub-editor: Lesley Hoye Email: [email protected] Graphic Designer: Kate O’Dea Email: [email protected] For an electronic version of this issue, please visit www.howtotreat.com.au You can also visit the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia’s website at www.rcpa.edu.au Click on Library and Publications, then Common Sense Pathology. -

Sourcebook in Forensic Serology, Immunology, and Biochemistry: Unit

U. S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice Sourcebook in Forensic Serology, Immunology, and Biochemistry Unit M:Banslations of Selected Contributions to the Original Literature of Medicolegal Examinations of Blood and Body Fluids - a publication of the National Institute of Justice About the National Institute of Justice The National lnstitute of Justice is a research branch of the U.S. Department of Justice. The Institute's mission is to develop knowledge about crime. its causes and control. Priority is given to policy-relevant research that can yield approaches and information State and local agencies can use in preventing and reducing crime. Established in 1979 by the Justice System Improvement Act. NIJ builds upon the foundation laid by the former National lnstitute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice. the first major Federal research program on crime and justice. Carrying out the mandate assigned by Congress. the National lnstitute of Justice: Sponsors research and development to improve and strengthen the criminal justice system and related civil justice aspects, with a balanced program of basic and applied research. Evaluates the effectiveness of federally funded justice improvement programs and identifies programs that promise to be successful if continued or repeated. Tests and demonstrates new and improved approaches to strengthen the justice system, and recommends actions that can be taken by Federal. State. and local governments and private organbations and individuals to achieve this goal. Disseminates information from research. demonstrations, evaluations. and special prograrris to Federal. State. and local governments: and serves as an international clearinghouse of justice information. Trains criminal justice practitioners in research and evaluation findings. -

Insulin Autoimmune Syndrome in an Occidental Woman

case report Insulin autoimmune syndrome in an occidental woman: a case report and literature review 1 Serviço de Endocrinologia e Diabetes, Hospital Universitário Mariella Zaiden Rezende Reis1, Virgínia Oliveira Fernandes1, Walter Cantídio – Faculdade de Eveline Gadelha Pereira Fontenele1,2, Ana Paula Abreu Martins Sales1,3, Medicina, Universidade Federal do Renan Magalhães Montenegro Junior1, Ana Rosa Pinto Quidute1,4 Ceará (UFC), Fortaleza, CE, Brasil 2 Núcleo de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento de Medicamentos (NPDM), Departamento de Medicina, Faculdade de Medicina, SUMMARY Universidade Federal do Ceará Insulin autoimmune syndrome (IAS, Hirata’s disease) is a rare hypoglycemic disorder characterized (UFC), Fortaleza, CE, Brasil 3 Faculdade de Medicina, by spontaneous hypoglycemia associated with extremely high circulating insulin levels and positive Universidade de Fortaleza anti-insulin antibody results. Thus far, most cases have been reported in Asian countries, notably (Unifor), Fortaleza, CE, Brasil Japan, with few cases reported in western countries. As a possible cause, it is associated with the 4 Núcleo de Pesquisa e use of drugs containing sulfhydryl radicals, such as captopril. This report refers to a 63-year-old Desenvolvimento de Medicamentos female Brazilian patient with a history of postprandial hypoglycemia. After extensive investigation (NPDM), Faculdade de Medicina, and exclusion of other causes, her hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia was considered to have likely Departamento de Fisiologia e Farmacologia, Universidade Federal been induced by captopril. Most cases of IAS are self-limiting. However, dietary management, do Ceará (UFC), Fortaleza, CE, Brasil corticosteroids, plasmapheresis, and rituximab have already been used to treat patients with IAS. In our case, after discontinuation of captopril, an initial decrease in insulin autoantibody levels was Correspondence to: observed followed by improvement in episodes of hypoglycemia. -

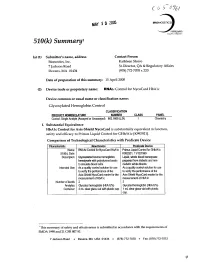

510(K) Summary

MAY 1 Z005 ,ERos 510(k) Summary, (a) (1) Submitter's name, address Contact Person Bionostics, Inc. Kathleen Storro 7 Jackson Road Sr.Director, QA & Regulatory Affairs Devens, MA 01434 (978) 772-7070 x 220 Date of preparation of this summary: 15 April 2005 (2) Device trade or proprietary name: RNAic Control for NycoCard HbAlc Device common or usual name or classification name: Glycosylated Hemoglobin Control CLASSIFICATION PRODUCT NOMENCLATURE NUMBER CLASS PANEL Control, Single Analyte (Assayed or Unassayed) 862.1660 (JJX) I Chemistry I. Substantial Equivalence HbAlc Control for Axis-Shield NycoCard is substantially equivalent in function, safety and efficacy to Primus Liquid Control for GHb/Alc [K9929211. Comparison of Technological Characteristics with Predicate Device Characteristic New Device Predicate Device Name: RNAIc Control for NycoCard HbAlc Primus Liquid Control for GHb/Alc 510(k), Date: K992921, 11/12/1999 Description: Glycosolated bovine hemoglobin Liquid, whole blood hemolysate hemolysate with polystyrene beads prepared from diabetic and non- to simulate blood cells. diabetic whole bloods. Intended Use: As a quality control solution for use As a quality control solution for use to verify the performance of the to verify the performance of the Axis-Shield NycoCard reader for the Axis-Shield NycoCard reader for the measurement of HbAlc measurement of HbAlc Number of levels: 2 2 Analytes: Glycated hemoglobin (HbAlc%) Glycated hemoglobin (HbAlc%) Container: 3 mL clear glass vial with plastic cap 1 mL clear glass vial with plastic cap 'This summary of safety and effectiveness is submitted in accordance with the requirements of SMDA 1990 and 21 CFR 807.92. 7 Jackson Road · Devens, MA USA 01434 · (978) 772-7070 * Fax: (978) 772-7072 q9 Characteristic New Device Predicate Device Semology Testing of No serology testing is necessary.