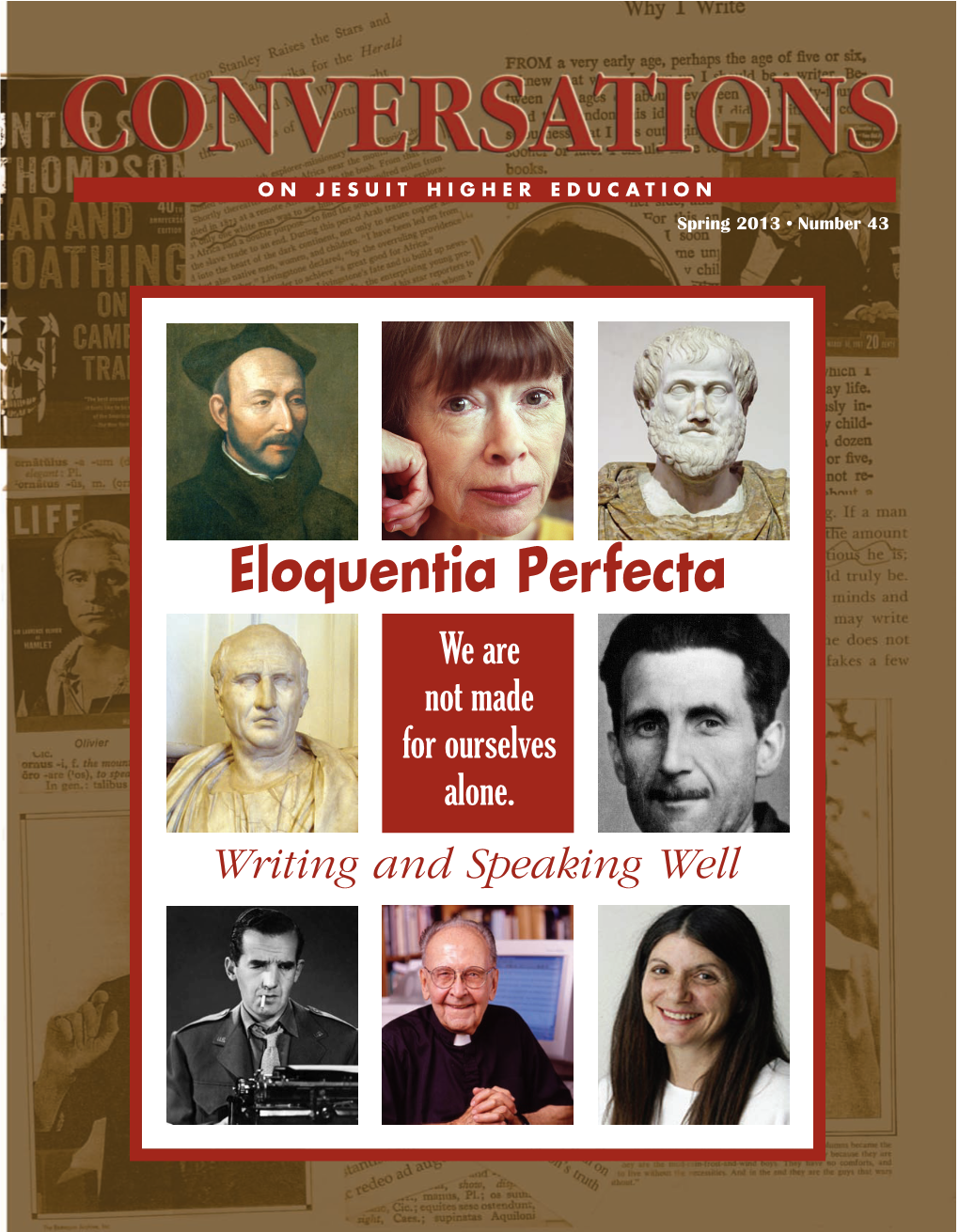

Conversations Eloquentia Perfecta.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Catalog for 2021-2022

Saint Ignatius High School 2021-2022 Course Catalog T ABLE OF CONTENTS I. Curriculum Overview II. General Information III. Typical Progressions IV. Course Registration Info V. Course Catalog: English Fine Arts Health/Physical Education History Languages Mathematics Science Theology 1 C URRICULUM OVERVIEW (return to Table of Contents) “A Saint Ignatius education does not exist to make you better than others; it exists to make you better for others.” This quote from our beloved friend Mr. Jim Skerl ‘74 sums up everything we do at Saint Ignatius High School. As a Jesuit high school, we strive not only to meet the standards of the Ohio Department of Education or even the standards of the many excellent colleges and universities that we send our students to after their four years with us. We strive to educate the whole person, mind, body and soul, and to point that education towards the service of God’s people. We strive to teach our students to be “Men for Others”. The curriculum outlined in these pages is the primary way we form our students and is the only way that every single one of our students is guaranteed to experience. There are, of course, many wonderful extracurricular opportunities but it is our academic curriculum that binds us together as Ignatius men forever. It is the daily experience that each one of our students has during his four years here. As such, we treat each component of this curriculum with respect knowing that it all contributes to the formation of the graduate at graduation as a man who is open to growth, intellectually competent, religious, loving, and committed to doing justice. -

Quintilian and the Jesuit Ratio Studiorum

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1939 Quintilian and the Jesuit Ratio Studiorum Joseph Robert Koch Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Koch, Joseph Robert, "Quintilian and the Jesuit Ratio Studiorum" (1939). Master's Theses. 471. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/471 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1939 Joseph Robert Koch ~' ------------------------------------------------. QUINTILIAN AND THE JESUIT RATIO STUDIORUM J by ., Joseph Robert Koch, S.J. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Loyola University. 1939 21- TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I Introduction 1 Chapter II Quintilian's Influence on 11 the Renaissance Educators Chapter III Quintilian's Ideal Orator 19 and the Jesuit Eloquentia Perfecta J " Chapter IV The Prelection 28 Chapter V Composition and Imitation 40 Chapter VI Enru.lation 57 Chapter VII Conclusion 69 A' ~J VITA AUCTORIS Joseph Robert Koch, S.J. was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, April 13, 1913. After receiving his elementary education at the Ursuline Academy he entered St. Xavier' High School, CinCinnati, in September, 1926. He grad uated from St. Xavier in June, 1930 and entered the Society of Jesus at Milford, Ohio, in August of th' " same year. -

Course Catalog

Saint Ignatius High School 2020-2021 Course Catalog T ABLE OF CONTENTS I. Curriculum Overview II. General Information III. Typical Progressions IV. Course Registration Info V. Course Catalog: English Fine Arts Health/Physical Education History Languages Mathematics Science Theology 1 C URRICULUM OVERVIEW (return to Table of Contents) “A Saint Ignatius education does not exist to make you better than others; it exists to make you better for others.” This quote from our beloved friend Mr. Jim Skerl ‘74 sums up everything we do at Saint Ignatius High School. As a Jesuit high school, we strive not only to meet the standards of the Ohio Department of Education or even the standards of the many excellent colleges and universities that we send our students to after their four years with us. We strive to educate the whole person, mind, body and soul, and to point that education towards the service of God’s people. We strive to teach our students to be “Men for Others”. The curriculum outlined in these pages is the primary way we form our students and is the only way that every single one of our students is guaranteed to experience. There are, of course, many wonderful extracurricular opportunities but it is our academic curriculum that binds us together as Ignatius men forever. It is the daily experience that each one of our students has during his four years here. As such, we treat each component of this curriculum with respect knowing that it all contributes to the formation of the graduate at graduation as a man who is open to growth, intellectually competent, religious, loving, and committed to doing justice. -

A Freirean-Jesuit Perspective

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Masters Essays Master's Theses and Essays Spring 2020 REIMAGINING REFLECTION IN FIRST-YEAR COMPOSITION: A FREIREAN-JESUIT PERSPECTIVE Adrianna Deptula Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons REIMAGINING REFLECTION IN FIRST-YEAR COMPOSITION: A FREIREAN-JESUIT PERSPECTIVE An Essay Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies College of Arts & Sciences of John Carroll University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Adrianna Deptula 2020 INTRODUCTION The ubiquitous bell tower at John Carroll University looms over every building, asserting itself from almost every spot on campus. Often associated with the school’s Jesuit heritage, the tower traditionally appears in prospective student brochures, alumni letters, public photography, and student shirts that are bought in the bookstore. One semester while teaching directly under the tower, in the only classroom on the third floor of the Administration Building, my class and I began every lesson after the bell marked the hour with its permeating chimes. The clock’s regular chiming informs the campus community of the time but also draws faculty, students, and staff together to recognize and center themselves within the present moment: an important skill that lies at the center of Jesuit education. At John Carroll University whose mission is to transform students into ethical and well-informed scholars who commit themselves to the common good, I began thinking about how I could further foster these Ignatian values and the subsequent focus on reflection in my composition course, EN 125, Seminar on Academic Writing. -

Georgetown at Two Hundred: Faculty Reflections on the University's Future

GEORGETOWN AT Two HUNDRED Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown GEORGETOWN AT Two HUNDRED Faculty Reflections on the University's Future William C. McFadden, Editor Georgetown University Press WASHINGTON, D.C. Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown Copyright © 1990 by Georgetown University Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Georgetown at two hundred : faculty reflections on the university's future / William C. McFadden, editor. p. cm. ISBN 0-87840-502-X. — ISBN 0-87840-503-8 (pbk.) 1. Georgetown University—History. 2. Georgetown University— Planning. I. McFadden, William C, 1930- LD1961.G52G45 1990 378.753—dc20 90-32745 CIP Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown FOR THE GEORGETOWN FAMILY — STUDENTS, FACULTY, ADMINISTRATORS, STAFF, ALUMNI, AND BENEFACTORS, LET US PRAY TO THE LORD. Daily offertory prayer of Brian A. McGrath, SJ. (1913-88) Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown Contents Foreword ix Introduction xi Past as Prologue R. EMMETT CURRAN, S J. Georgetown's Self-Image at Its Centenary 1 The Catholic Identity MONIKA K. HELLWIG Post-Vatican II Ecclesiology: New Context for a Catholic University 19 R. BRUCE DOUGLASS The Academic Revolution and the Idea of a Catholic University 39 WILLIAM V. O'BRIEN Georgetown and the Church's Teaching on International Relations 57 Georgetown's Curriculum DOROTHY M. BROWN Learning, Faith, Freedom, and Building a Curriculum: Two Hundred Years and Counting 79 JOHN B. -

706 Cinthia Gannett and John C. Brereton, Eds. This Collection Of

706 Book Reviews Cinthia Gannett and John C. Brereton, eds. Traditions of Eloquence: The Jesuits and Modern Rhetorical Studies. New York: Ford- ham University Press, 2016. Pp. xx + 444. Hb, $125. Pb, $45. This collection of thoughtful essays on the role of rhetoric in Jesuit colleges and universities from their origins to the present arises from the editors’ inter- est in rhetorical traditions and from current conversations among Jesuits and their collaborators on pedagogy, educational renewal, and the order’s efforts to update the historical missions and ministries of the Society of Jesus. From the sixteenth century until roughly the mid-twentieth century the required study of rhetoric in Jesuit schools aimed at that singular endowment of the well edu- cated individual—eloquentia perfecta, that harmonious union of eloquence and wisdom, “that blend of verbal facility and ethical action” (39). This work reviews the privileged status rhetoric once enjoyed but has since lost, and as- sesses the relevance and place of rhetoric in Jesuit education today. Divided in three parts, these twenty-five essays (with foreword, preface, and introduction) examine the Jesuit rhetorical tradition in Europe and parts of North America before the suppression of the Society of Jesus (1773) and from its restoration (1814) to the present. They probe critically the curricula of some Jesuit universities today for surviving elements of that tradition, whether in various pedagogical methods, in courses on rhetoric, in writing centers and programs for writing and speaking across the curriculum. The essays make the reader aware that the idea of eloquentia perfecta in today’s academic milieu is not one grasped easily by many non-Jesuit faculty, nor one that all faculty have been eager to embrace. -

Of Many Things

THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY MAY 16, 2011 $3.50 OF MANY THINGS PUBLISHED BY JESUITS OF THE UNITED STATES hortly before the beatification humanity. The saints would be the first of John Paul II, there was con - to admit this. Sanctity does not mean EDITOR IN CHIEF Drew Christiansen, S.J. sternation in some circles about perfection. So can his supporters admit Sthe perceived rush to canonize him. that John Paul was human and made EDITORIAL DEPARTMENT The Vatican’s Congregation for the mistakes? And can critics forgive MANAGING EDITOR Causes of Saints had waived the nor - him the errors he made? Robert C. Collins, S.J. mal five-year waiting period before Second, you do not have to agree EDITORIAL DIRECTOR beginning the proceedings. There were with everything a saint did to admire Karen Sue Smith also concerns raised, in light of what him (or her). One of my favorite saints ONLINE EDITOR have been seen as his failings as pope, is Thomas More, the 16th-century Maurice Timothy Reidy about whether he deserved to be so English martyr, known to most people CULTURE EDITOR honored. from the play and film “A Man for All James Martin, S.J. As for the rush, I am in favor of Seasons.” But I do not agree—to put it LITERARY EDITOR every candidate being subject to the mildly—with the burning of heretics, Patricia A. Kossmann same careful process of examination. It which More approved. POETRY EDITOR is unfair to favor someone because he The Vatican noted that Pope James S. -

Final Core Proposal

Final Core Proposal core <[email protected]> Fri 1/31/2020 7:24 PM 1 attachments (825 KB) Final CORE Proposal 1.31.2020.pdf Dear Members of the SLU Community, On behalf of the University Undergraduate Core Committee, I am happy to submit to you the final iteration of our University Core Proposal. The first iteration of this curriculum, released on October 1st, 2019, was the result of over four years of dedicated, university-wide collaboration and consultation. Since then, the UUCC has been reviewing the official responses from all Colleges and Schools that deliver undergraduate programs. In addition to this final University Core Proposal document, the UUCC will also provide detailed College and School-specific responses to questions and requests. The UUCC will hold two open fora to present this final version and answer questions from the SLU community. These will be held as follows: Open Fora South Campus - Monday, 2/10 from 12:00 - 1:00 in Allied Health #1043 Open Fora North Campus - Wednesday, 2/12 from 4:00 - 5:00 in Morrissey Hall #0600 We ask that all SLU Colleges and Schools vote on adoption of this new University Core curriculum no later than March 20th, 2020. Collegially, Ellen Crowell Director of the University Core Associate Professor of English Saint Louis University [email protected] PROPOSAL: UNIVERSITY CORE Proposal: University Core Submitted to the SLU community (St. Louis and Madrid) by the University Undergraduate Core Committee (UUCC) January 31, 2020 One University :: One Core The University Core at Saint Louis University prepares all students to be intellectually flexible, creative, and reflective critical thinkers in the spirit of the Catholic, Jesuit tradition. -

Good Rhetoric from the Classical to the Jesuits; Or on Αγαθός Λόγος Andrew J

The Criterion Volume 2018 | Issue 1 Article 8 5-6-2018 Good Rhetoric from the Classical to the Jesuits; or On αγαθός λόγος Andrew J. Wells College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/criterion Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Wells, Andrew J. (2018) "Good Rhetoric from the Classical to the Jesuits; or On αγαθός λόγος," The Criterion: Vol. 2018 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/criterion/vol2018/iss1/8 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The rC iterion by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. Good Rhetoric from the Classical to the Jesuits; or, On ἀγαθός λόγος A number of Greek philosophers attempted to assess rhetoric in hopes of understanding the difference between ἀγαθός λόγος "good speech" and κακός λόγος "bad speech." Today, I draw upon a few Greek philosophers to further pursue the question of how to classify rhetoric as ἀγαθός. As a student at the College of the Holy Cross, I am also aware of the long-standing tradition in Jesuit education concerning the pursuit of Eloquentia Perfecta. While understanding Eloquentia Perfecta, I hope to unlock the dichotomy between " ἀγαθός" and " κακός" rhetoric by analyzing separate schools of thought from Ancient Greek Philosophy and then applying their analysis to the Jesuit tradition. Socrates, who believed good rhetoric accesses truth and virtue, and Gorgias, who believed good rhetoric accesses the intended audience as a result of an effective rhetorician, are my main two classical rhetoricians. -

Philosophy 1

Philosophy 1 • Writing sample (5 - 20 pages, submitted electronically, via the online PHILOSOPHY application) • Three letters of recommendation (submitted directly by referees via For more than 150 years, Fordham’s philosophy department has trained the online application) students and teachers in the Jesuit tradition. As part of that tradition, • Official GRE scores (should be sent directly by the testing service our program is grounded in a strong understanding of the history of to the Office of Graduate Admissions, Fordham University, Graduate philosophy from the ancient world to the contemporary. School of Arts and Sciences – Code #2259). Fordham highly values philosophical pluralism. Our faculty represent • English Profiency - International applicants whose native language diverse schools and perspectives, and students enjoy an uncommonly is not English are required to complete and submit to GSAS prior well-rounded philosophical education. All graduate students take courses to matriculation their official scores from the Test of English spanning the history of philosophy, including contemporary philosophy. as a Foreign Language (TOEFL). GSAS will also consider a student’s International English Language Testing System (IELTS) Fordham’s philosophy department is renowned for its strengths in —Cambridge English Proficiency Level language testing results. Continental philosophy, Epistemology, Ethics, Medieval Philosophy, Competitive applicants will have earned TOEFL scores above 100 Metaphysics, and Philosophy of Religion. and/or an IELTS score of 7.5 or higher. The Jesuit tradition emphasizes eloquentia perfecta, effective and The department may prescribe additional coursework for students whose clear writing and speaking. Fordham’s philosophy graduate students backgrounds are deficient, in which case the time limit for completion of are therefore strongly encouraged to publish and present their original coursework will be extended. -

Cinthia Gannett and John C. Brereton (Eds.)

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), Book Review 338–340 1932–8036/2017BKR0009 Cinthia Gannett and John C. Brereton (Eds.), Traditions of Eloquence: The Jesuits and Modern Rhetorical Studies, New York, NY: Fordham University Press, 2016, 487 pp., $125.00 (hardcover), $45.00 (paperback). Reviewed by Thomas A. Discenna Oakland University, USA In the aftermath of what was perhaps the least eloquent election in U.S. history, it is difficult not to read to this collection of essays without a certain longing, bordering on nostalgia, for the eloquentia perfecta that was so cherished and propagated in Jesuit higher education. Traditions of Eloquence: The Jesuits and Modern Rhetorical Studies is divided into three sections that trace the origins, dissemination and impact, and future prospects of the “classical ideal of the good person writing and speaking skillfully for the public good” (p. 165). The essays that compose this volume are primarily intended for scholars and teachers in the composition tradition of rhetorical studies and will mainly be of interest to specialists in this area. However, this work may also prove useful to historians and theorists of higher education, especially in the critical study of higher education, as many of the themes that emerge in its 26 essays speak profoundly to contemporary problems plaguing the modern university. Moreover, as alluded to in the opening of this review, there are also sociocultural and political implications embedded in these works that reflect many of the pressing issues of our current age. The Jesuits, it is claimed here, administered the first system of higher education in the world, with a professed goal of bringing education to people remote from the centers of power both geographically and by economic circumstances. -

Conversations

ON JESUIT HIGHER EDUCATION Fall 2013 • Number 44 Justice in Jesuit Higher Education Art and Justice • Follow the Money • Talking Back FALL 2013 NUMBER 44 Members of the National Seminar on ON JESUIT HIGHER EDUCATION Jesuit Higher Education Laurie Ann Britt-Smith University of Detroit Mercy Lisa Sowle Cahill Justice in Jesuit Higher Education Boston College Susanne E. Foster Marquette University Features Patrick J. Howell, S.J. Seattle University 2 Higher Education, Justice, and the Church, Margaret Farley Steven Mailloux 6 The Issue of Same-sex Marriage, Ennio Mastroianni Loyola Marymount University 8 Heterosexism: An Ethical Challenge, Patrick Hornbeck Diana Owen Georgetown University 10 Accompaniment, Service, and Advocacy, David Hollenbach, S.J. Stephen C. Rowntree, S.J. Loyola University New Orleans Follow the Money Alison Russell Xavier University 13 Just Employment and Investment Policies, Josh Daly Edward W. Schmidt, S.J. 14 Financial Aid: Need Based or Merit Based? Jeff von Arx, S.J. Institute of Jesuit Sources Sherilyn G.F. Smith Le Moyne College Art and Justice education William E. Stempsey, S.J. College of the Holy Cross 16 Justice by Design, Mary Beth Akre 17 Speaking of Justice, Greg Grobis Conversations is published by the 18 Amplifying the Diminished Voice, Dan Pitera National Seminar on Jesuit Higher Education, which is jointly spon - 19 Community through Art and Design, Janden Richards and Wanda Sullivan sored by the Jesuit Conference Board and the Board of the Association of Jesuit Colleges and 22 Undocumented Students, Rick Ryscavage, S.J. Universities. The opinions stated herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the JC or the AJCU.