Lewis Latimer: the Shadow Behind the Light Bulb Garrett R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Stanley Lighted a Town and Powered an Industry

William Stanley Lighted a Town and Powered an Industry by Bernard A. Drew and Gerard Chapman preface by Samuel Sass Berkshire History Fall 1985 Vol. VI No. 1 Published by the Berkshire County Historical Society Pittsfield Massachusetts Preface: At a meeting of engineers in New York a half century ago, a paper was read which contained the following description of a historic event in the development of electrical technology: For the setting we have a small town among the snow-clad New England Hills. There a young man, in fragile health, is attacking single-handed the control of a mysterious form of energy, incalculable in its characteristics, and potentially so deadly that great experts among his contemporaries condemned attempts to use it. With rare courage he laid his plans, with little therapy or precedent to guide him; with persistent experimental skill he deduced the needed knowledge when mathematics failed; with resourcefulness that even lead him to local photographers to requisition their stock of tin-type plates (for the magnetic circuit of his transformer), successfully met the lack of suitable materials, and with intensive devotion and sustained effort, despite poor health, he brought his undertaking, in an almost unbelievably short time, to triumphant success. This triumphant success occurred in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, in 1886, and the young man in fragile health was William Stanley. A century ago he demonstrated the feasibility of transforming to a higher level the generated alternating current voltage, for transmission at a distance, and reducing it at the consumer end to a usable level. One hears or reads on occasion that Stanley “invented” the transformer. -

Trow Point and the Disappearing Gun the Concrete Structure in Front of You Is What Remains of an Innovative Experiment in Gun Technology

Trow Point and the Disappearing Gun The concrete structure in front of you is what remains of an innovative experiment in gun technology. The trial of the ‘Hiram Maxim Disappearing Gun’ took place here on the 16th December 1887. Big guns A novel idea... Training ground The late 19th century was an era of huge change in warfare and weaponry Although the gun fired without problem, the water-and-air-pressure that would continue through to the major world wars. Gun technology moved powered raising and lowering mechanism was too slow and was from unreliable, dangerous and erratic cannons to long range, accurate and never used in combat. It took 8 hours to pressurise the pump before quick loading weapons. The ‘Mark IV 6 inch breech loading gun’ was a it was operational and in very cold weather the water would freeze, powerful example of the scale of change. It had a firing range of 30,000ft making it impossible to fire at all! (9000m), twice that of previous guns, and was capable of punching holes There were other attempts to develop retractable mounts but they through the iron armour of enemy ships. never went into widespread service. As the firing range of guns improved there was little need to hide soldiers from the enemy Now you see it...now you don’t! when reloading and it wasn’t long before attack from the air What was unique about this gun replaced the threat from the sea. emplacement at Trow Point was that it trialled a mounting system that would The gun and its mounting was removed, leaving just this concrete allow the Mark IV 6” gun to be raised and lowered. -

Sir Hiram S. Maxim Collection

Sir Hiram S. Maxim Collection 2001 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Sir Hiram S. Maxim Collection NASM.1989.0031 Collection Overview Repository: National Air and Space Museum Archives Title: Sir Hiram S. Maxim Collection Identifier: NASM.1989.0031 Date: 1890-1916 (bulk 1890-1894, 1912) Extent: 1.09 Cubic feet ((1 records center box)) Creator: Maxim, Hiram H. Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Hiram H. Maxim, gift, 1989, 1989-0031, NASM Restrictions No restrictions on access Conditions Governing Use Material is subject to Smithsonian Terms of Use. Should you wish to use NASM material in any medium, please submit an Application -

Historic Amusement Parks and Fairground Rides Introductions to Heritage Assets Summary

Historic Amusement Parks and Fairground Rides Introductions to Heritage Assets Summary Historic England’s Introductions to Heritage Assets (IHAs) are accessible, authoritative, illustrated summaries of what we know about specific types of archaeological site, building, landscape or marine asset. Typically they deal with subjects which lack such a summary. This can either be where the literature is dauntingly voluminous, or alternatively where little has been written. Most often it is the latter, and many IHAs bring understanding of site or building types which are neglected or little understood. Many of these are what might be thought of as ‘new heritage’, that is they date from after the Second World War. With origins that can be traced to annual fairs and 18th-century pleasure grounds, and much influenced by America’s Coney Island amusement park of the 1890s, England has one of the finest amusement park and fairground ride heritages in the world. A surprising amount survives today. The most notable site is Blackpool Pleasure Beach, in Lancashire, which has an unrivalled heritage of pre-1939 fairground rides. Other early survivals in England include scenic railways at Margate and Great Yarmouth, and water splash rides in parks at Kettering, Kingston-upon-Hull and Scarborough that date from the 1920s. This guidance note has been written by Allan Brodie and edited by Paul Stamper. It is one is of several guidance documents that can be accessed HistoricEngland.org.uk/listing/selection-criteria/listing-selection/ihas-buildings/ Published by Historic England June 2015. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. HistoricEngland.org.uk/listing/ Front cover A modern aerial photograph of Blackpool Pleasure Beach showing the complex landscape that evolved during the 20th century. -

The History of Sir Hiram Maxim

The History of Sir Hiram Maxim On a small hill overlooking Dexter's Lake Wasookeag on a June day in 1890, a gathering of townspeople watched history in the making as bullets whizzed into the lake waters at a rate of 666 per minute. The small-town quiet was shattered as the gun swayed back and forth to show how a fast-moving army could be cut down in minutes. From that location, about 10 miles from his Sangerville home, Sir Hiram Maxim's gun entered the battlefields of the Russo- Japanese War and later World War I, World War II, and even the battlefields of Korea and Vietnam. As a boy, Hiram Maxim lived at Brockway Mills, located off Silvers Mills Road. Born on the fifth of February, 1840 in a less than modest home - on a small knoll overlooking a stream, he tended sheep throughout the summer months. Legend has it, as a young lad he and his brother Hudson stood atop a large boulder outside their home and with raised arms pledged to themselves that someday they would become famous. Both men achieved fame and garnered themselves a place in the history books. Hiram's only schooling was what he gleaned from five years of learning in a one-room Sangerville schoolhouse. At the age of 14, he was apprenticed to Daniel Sweat, an East Corinth carriage maker who had recently returned to Sangerville. Hiram went to work for Mr. Sweat in Abbott and it was there that he perfected his first invention - an automatic mousetrap that soon rid the Abbot grist mill of mice. -

American and German Machine Guns Used in WWI

John Frederick Andrews Novels of the Great War American and German Machine Guns Used in WWI The machine gun changed the face of warfare in WWI. The devastating effects of well-emplaced machine guns against infantry and cavalry became brutally evident in the 1st World War. It changed infantry tactics forever. The US Marines and Army had several machine guns available during the war. This brief will discuss crew-served machine guns only. Man-portable automatic rifles are discussed in another article. The Lewis gun is mentioned here for completeness. The Marine 1st Machine Gun Battalion, commanded by Maj. Edward Cole trained with the Lewis gun before shipping overseas. The gun had been used by the British with good effect. Cole’s men trained with at the Lewis facility in New York. At that point, the plan was for each company to have an eight-gun machine gun platoon. A critical shortage in the aviation community stripped the Marines of their Lewis guns before they shipped to France. The Lewis Gun weighed 28 pounds and was chambered in the .303 British, .30.06 Springfield, and 7.92x57 mm Mauser. They were fed by a top-mounted magazine that could hold 47 or 96 rounds. Rate of fire was 500-600 rounds per minute with a muzzle velocity of 2,440 feet per second and an effective range of 880 yards and a maximum of 3,500 yards. The infantry model is shown below. John Frederick Andrews Novels of the Great War When the Lewis guns were taken away, the Hotchkiss Model 1914 was issued in its place. -

Zaharoff the Armaments King

ZAHAROFF THE ARMAMENTS KING by Robert Neumann TRANSLATED BY R. T. CLARK READERS' UNION LIMITED GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD "Zaharoff the Armaments King" was first published in England in 1935 and a new impression followed in 1936. Robert Neumann has, for Readers' Union edition (1938), brought his Zaharoff "legend" up to date and revised various parts of the text. To Readers' Union edition has been added a portrait of Zaharoff. ZAHAROFF POINT This edition, for Readers' Union members only, is possible by co-operative reader demand and by the sacrifice of ordinary profit margins by all concerned. Such conditions cannot apply under the normal hazards of book production and distribution. Reader commentaries on Zaharoff the Armaments King will be found in July 1938 issue of Readers' News given free with this volume. Membership of Readers' Union can be made at any booksellers' shop. MADE 1938 IN GREAT BRITAIN. PRINTED BY C. TINLING AND CO., LTD., LIVERPOOL, LONDON AND PRESCOT, FOR READERS' UNION LTD. REGISTERED OFFICES: CHANDOS PLACE BY CHARING CROSS, LONDON, ENGLAND. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE THE DIFFICULTIES OF A BIOGRAPHER 9 1. ON THE TRACK OF A YOUNG MAN FROM THE EAST 19 A Piece of Universal History-A Piece of Family History-The Child is Father of the Man-The Case of Haim Sahar of Wilkomir-Sir Basil Casanova-The Detective at Work-The First Conquest of Athens n. DEAD MEN OVERTURE 79 The Duel with Mr. Maxim-A Stay in Russia Cherchez la femme-Clouds over South America -In the Prime of Life-a portrait-Maxims for Budding Armament Kings-The Duel with a Gentleman from Le Creusot-The Noise of Battle-In the Paris Press-Spring Interlude, 191 4 Ill. -

Mechanical Pleasures: the Appeal of British Amusement Parks 1900-1914

1 Chapter XX Mechanical Pleasures: The Appeal of British Amusement Parks, 1900–1914 Josephine Kane In April 1908, the World’s Fair published an account of progress at the White City exhibition ground, which was nearing completion at London’s Shepherd’s Bush.1 Under the creative control of famed impresario Imre Kiralfy, a series of grand pavilions and landscaped grounds were underway, complete with what would become London’s first purpose-built amusement park.2 The amusements at White City had been conceived as a light-hearted sideline for visitors to the inaugural Franco–British Exhibition, but proved just as popular as the main exhibits. The spectacular rides towered over the whole site and were reproduced in countless postcards and souvenirs. Descriptions of the ‘mechanical marvels’ at the amusement park dominated coverage in the national press. The Times reported on the long queues for a turn on the Flip Flap – a gigantic steel ride which carried passengers back and forth in a 200-foot arch – and of the endless line of cars crawling to the top of the Spiral Railway before ‘roaring and rattling, round and round to the bottom’ (Figure XX.1).3 The Franco–British Exhibition was visited by 8 million people, but it was the amusement park which captured the public imagination and made a lasting impression.4 1 The World’s Fair is a national amusement trade newspaper, published weekly from June 1904. Providing news and commentary about the industry, it was read by fairground and amusement park operators across England, who used its pages to buy or sell rides and equipment, to advertise jobs or services and to let or request concessions pitches. -

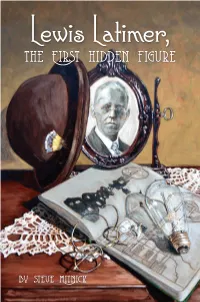

Lewis Latimer, the First Hidden Figure

Lewis Latimer, the First hidden figure by steve Mitnick Lewis Latimer, the First hidden figure Also by Steve Mitnick Lines Down How We Pay, Use, Value Grid Electricity Amid the Storm Lewis Latimer, The First Hidden Figure By Steve Mitnick Public Utilities Fortnightly Lines Up, Inc. Arlington, Virginia © 2021 Lines Up, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. The digital version of this publication may be freely shared in its full and final format. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020947176 Author: Steve Mitnick Editor: Lori Burkhart Assistant Editor: Angela Hawkinson Production: Mike Eacott Cover Design: Paul Kjellander Illustrations: Dennis Auth For information, contact: Lines Up, Inc. 3033 Wilson Blvd Suite 700 Arlington, VA 22201 First Printing, October 2020 V. 1.02 ISBN 978-1-7360142-0-2 Printed in the United States of America. To my boyhood heroes Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson, Elston Howard and Al Downing The cover painting entitled “Hidden in Bright Light,” is by Paul Kjellander, the President of the Idaho Public Utilities Commission and President of the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners, commonly referred to by its acronym NARUC. Table of Contents A Word of Inspiration by David Owens ................................ ix Sponsoring this Book and the PUF Latimer Scholarship Fund ............... xii Acknowledgements .............................................. xviii Note to Readers .................................................. xix Foreword ...................................................... xxiv Introduction ...................................................... 1 Chapter 1. The First Hidden Figure .............................. 7 First, and Alone .......................................... -

Advanced Foreign Language Learning: a Challengeto College Programs

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 482 772 FL 027 917 AUTHOR Byrnes, Heidi, Ed.; Maxim, Hiram H., Ed. TITLE Advanced Foreign Language Learning: A Challengeto College Programs. Issues in Language Program Direction. ISBN ISBN-141300040-1 PUB DATE 2004-00-00 NOTE 219p.; Prepared by the American Association of University Supervisors, Coordinators, and Directors of ForeignLanguage Programs. AVAILABLE FROM Heinle, 25 Thomson Place, Boston, MA 02210. Tel: 800-730-2214 (Toll Free); Fax: 800-730-2215 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.heinle.com. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Advanced Students; Business Communication; College Students; Curriculum Design; Graduate Study; *Heritage Education; Higher Education; *Language Proficiency; Language Styles; Literacy; Second Language Instruction; Second Language Learning; Spanish; Study Abroad; *Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS Heritage Language ABSTRACT This book includes the following chapters: "Literacy and Advanced Foreign Language Learning: Rethinking he Curriculum" (RichardG. Kern); "A Template for Advanced Learner Tasks: Staging Genre Reading and Cultural Literacy Through the Precis" (Janet Swaffar); "Fostering Advanced L2 Literacy: A Genre-Based, Cognitive Approach" (Heidi Byrnes, Katherine A. Sprang); "Heritage Language Speakers and Upper-Division Language Instruction: Findings from a Spanish Linguistics Program" (Daniel J. Villa); "heritage Speakers' Potential for High-Level language Proficiency "(Olga Kagan, Dillon, Kathleen); "Study Abroad for Advanced Foreign Language Majors: Optimal Duration for Developing Complete Structures" (Casilde A. Isabelli); "'What's Business Got to Do with It?': The Unexplored Potential of Business Language Courses for Advanced Foreign Language Learning" (Astrid Weigert); "Fostering Advanced-Level language Abilities in Foreign Language Graduate Programs: Applications of Genre Theory" (Cori Crane, Olga Liamkina, Marianna Ryshina-Pankova); and "Expanding Visions for Collegiate Advanced Foreign Language Learning" (Hiram H. -

Hudson Maxim Photographs 1996.312

Hudson Maxim photographs 1996.312 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Hudson Maxim photographs 1996.312 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Organization of the Collection ...................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ...................................................................................................................................... -

“Whatever Happens, We Have Got, the Maxim, and They Have Not”: the Conspicuous Absence of Machine Guns in British Imperialist Imagery

43 THE CONSPICUOUS ABSENCE OF MACHINE GUNS “Whatever happens, we have got, the Maxim, and they have not”: The Conspicuous Absence of Machine Guns in British Imperialist Imagery by Ramey Mize “At frst, before fring, one felt a little gun shy. I well remember the Instructor say- ing, ‘It can’t hurt you, the bullets will come out the other end.’”1 –P. G. Ackrell In 1893 in Southern Africa, British colonial police slaughtered 1,500 Ndebele warriors, losing only four of their own men in the process.2 This astronomi- cal, almost unfathomable victory was earned not through superior strength, courage, or strategic skill, but because the British were armed with fve machine guns and the Ndebele were not.3 The invention and development of the machine gun by engineers such as Richard Gatling, William Gard- ner, and Hiram Maxim proved vital in the colonization and subjugation of Africa; although Zulu, Dervish, Herero, Ndebele, and Boer forces vastly outnumbered British settlers, all were rendered helpless in the face of the machine gun’s phenomenal frepower.4 These brutal imperial campaigns were subsequently met with a “mountain of print and pictures” in order to satiate the interests of an eager British public.5 Few artists contributed as prolifcally as Richard Caton Woodville, Jr. to the wealth of war imagery that colored the widely circulated illustrated newspapers.6 A self-professed “spe- cial war artist” of the 1880s and 1890s, albeit one who had never personally experienced battle,7 Woodville submitted thousands of drawings to a wide variety