Advanced Foreign Language Learning: a Challengeto College Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS MARCH 1, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 18 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] What’s Up With Strait Talk With Songwriter Dean Dillon Bryan’s ‘Down’ >page 4 As He Awaits His Hall Of Fame Induction Academy Of Country Life-changing moments are not always obvious at the time minutes,” says Dillon. “I was in shock. My life is racing through Music Awards they occur. my mind, you know? And finally, I said something stupid, like, Raise Diversity So it’s easy to understand how songwriter Dean Dillon (“Ten- ‘Well, I’ve given my life to country music.’ She goes, ‘Well, we >page 10 nessee Whiskey,” “The Chair”) missed the 40th anniversary know you have, and we’re just proud to tell you that you’re going of a turning point in his career in February. He and songwriter to be inducted next fall.’ ” Frank Dycus (“I Don’t Need Your Rockin’ Chair,” “Marina Del The pandemic screwed up those plans. Dillon couldn’t even Rey”) were sitting on the front porch at Dycus’ share his good fortune until August — “I was tired FGL, Lambert, Clark home/office on Music Row when producer Blake of keeping that a secret,” he says — and he’s still Get Musical Help Mevis (Keith Whitley, Vern Gosdin) pulled over waiting, likely until this fall, to enter the hall >page 11 at the curb and asked if they had any material. along with Marty Stuart and Hank Williams Jr. He was about to record a new kid and needed Joining with Bocephus is apropos: Dillon used some songs. -

Measuring Attitudes and Their Implications for Language Education: a Critical Assessment" (Stephen J

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 367 161 FL 021 883 AUTHOR Sadtono, Eugenius, Ed. TITLE Language Acquisition and the Second/Foreign Language Classroom. Anthology Series 28. INSTITUTION Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (Singapore). Regional Language Centre. REPORT NO RELC-P-393-91 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 225p.; Selected papers from the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO) Regional Language Centre (Singapore, 1991). For individual papers, see FL 021 884-889, FL 021 891, ED 337 047, and ED 338 037. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020' Collected Works Serials (022) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRI?TORS *Attitude Measures; Classroom Techniques; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; High Schools; Interaction; Journal Writing; Language Attitudes; *Language Research; *Learning Theories; Oral Language; *Personality Traits; Research Methodology; Research Needs; *Second Language Instruction; Second Language Learning; Student Characteristics; Student Motivation; Student Role; Teacher Education; Theory Practice Relationship ABSTRACT A selection of papers on second language learning includes: "Second Language Acquisition Research in the Language Classroom" (David Nunan); "A Place for Second Language Acquisition in Teacher Development and in Teacher Education Programmes" (Rod Bolitho); "Dimensions in the Acquisition of Oral Language" (Martin Bygate, Don Porter); "The Learner's Effort in the Language Classroom" (N. S. Prabhu); "Diary Studies of Classroom Language Learning: The Doubting Game and the Believing Game" (Kathleen M. Bailey); "Personality and Second-Language Learning: Theory, Research and Practice" (Roger Griffiths); "The Contribution of SLA Theories and Research to Teaching Language" (Andrew S. Cohen, Diane Larsen-Freeman, Elaine Tarone); "The Matched-Guise Technique for Measuring Attitudes and Their Implications for Language Education: A Critical Assessment" (Stephen J. -

William Stanley Lighted a Town and Powered an Industry

William Stanley Lighted a Town and Powered an Industry by Bernard A. Drew and Gerard Chapman preface by Samuel Sass Berkshire History Fall 1985 Vol. VI No. 1 Published by the Berkshire County Historical Society Pittsfield Massachusetts Preface: At a meeting of engineers in New York a half century ago, a paper was read which contained the following description of a historic event in the development of electrical technology: For the setting we have a small town among the snow-clad New England Hills. There a young man, in fragile health, is attacking single-handed the control of a mysterious form of energy, incalculable in its characteristics, and potentially so deadly that great experts among his contemporaries condemned attempts to use it. With rare courage he laid his plans, with little therapy or precedent to guide him; with persistent experimental skill he deduced the needed knowledge when mathematics failed; with resourcefulness that even lead him to local photographers to requisition their stock of tin-type plates (for the magnetic circuit of his transformer), successfully met the lack of suitable materials, and with intensive devotion and sustained effort, despite poor health, he brought his undertaking, in an almost unbelievably short time, to triumphant success. This triumphant success occurred in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, in 1886, and the young man in fragile health was William Stanley. A century ago he demonstrated the feasibility of transforming to a higher level the generated alternating current voltage, for transmission at a distance, and reducing it at the consumer end to a usable level. One hears or reads on occasion that Stanley “invented” the transformer. -

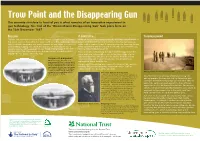

Trow Point and the Disappearing Gun the Concrete Structure in Front of You Is What Remains of an Innovative Experiment in Gun Technology

Trow Point and the Disappearing Gun The concrete structure in front of you is what remains of an innovative experiment in gun technology. The trial of the ‘Hiram Maxim Disappearing Gun’ took place here on the 16th December 1887. Big guns A novel idea... Training ground The late 19th century was an era of huge change in warfare and weaponry Although the gun fired without problem, the water-and-air-pressure that would continue through to the major world wars. Gun technology moved powered raising and lowering mechanism was too slow and was from unreliable, dangerous and erratic cannons to long range, accurate and never used in combat. It took 8 hours to pressurise the pump before quick loading weapons. The ‘Mark IV 6 inch breech loading gun’ was a it was operational and in very cold weather the water would freeze, powerful example of the scale of change. It had a firing range of 30,000ft making it impossible to fire at all! (9000m), twice that of previous guns, and was capable of punching holes There were other attempts to develop retractable mounts but they through the iron armour of enemy ships. never went into widespread service. As the firing range of guns improved there was little need to hide soldiers from the enemy Now you see it...now you don’t! when reloading and it wasn’t long before attack from the air What was unique about this gun replaced the threat from the sea. emplacement at Trow Point was that it trialled a mounting system that would The gun and its mounting was removed, leaving just this concrete allow the Mark IV 6” gun to be raised and lowered. -

Walker County Qualified Voter's List

WALKER COUNTY VOTER’S LIST Jasper Ala. Tues., Feb. 9, 2016 — Page 1 Walker County Qualified Voter’s List Humphrey, Danny Lee Usrey, Chase L STATE OF ALABAMA Ilarraza, Brittany Rebecca Vines, Rachel Sanders WALKER COUNTY Jackson, Angela R Waddell, Belinda Gail Reece James, Teddy R Waid, Vickie Griffin James, Jered Ray Waid, James Tyler Jean, Donald Duane Wakefield, Linda Rose I, Rick Allison, Judge of Probate in and for said State and County, certify that the following Jett, Nicholas Cody Walker, Denzal Devonta names have registered to vote as shown by the list submitted to my office by the Walker County Jett, Angela Brooke Warren, Billy Barry Johnson, Erik Landon Warren, Gwindola Board of Registrars on February 4, 2016, and will constitute the official voting list for the Presi- Johnson,Iii Ralph Edward Warren, Brandi Michelle Johnston, Dennis Ray Warren, Billy Michael dential Preference Primary Election and Statewide Primary Election to be held on Tuesday, Joiner, Crystal Marie Warren, Teresa Rose March 1, 2016. If your name was inadvertently omitted from this list, you have until 4:00 pm on Jones, Ricky R Watkins, Sarah Naomi Justice, Janet C Watts, Annie Mae Friday, February 12, 2016, to have your name added to the list at the Board of Registrar’s Office Justice, Timothy D Webb, Lowanda in the Walker County Courthouse. Kempf, Joann Frost White, Albert J Kennedy, Raymond Joseph Whited, Roger A Key, Teresia Ann Whitehead, Michael Reihee Kimbrough, Connie Carlton Whitley, Alvin Morgan Kizziah, Terry J Whitley, Cindy K Given under my hand and seal of office this 4th day of February 2016. -

Sir Hiram S. Maxim Collection

Sir Hiram S. Maxim Collection 2001 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Sir Hiram S. Maxim Collection NASM.1989.0031 Collection Overview Repository: National Air and Space Museum Archives Title: Sir Hiram S. Maxim Collection Identifier: NASM.1989.0031 Date: 1890-1916 (bulk 1890-1894, 1912) Extent: 1.09 Cubic feet ((1 records center box)) Creator: Maxim, Hiram H. Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Hiram H. Maxim, gift, 1989, 1989-0031, NASM Restrictions No restrictions on access Conditions Governing Use Material is subject to Smithsonian Terms of Use. Should you wish to use NASM material in any medium, please submit an Application -

Historic Amusement Parks and Fairground Rides Introductions to Heritage Assets Summary

Historic Amusement Parks and Fairground Rides Introductions to Heritage Assets Summary Historic England’s Introductions to Heritage Assets (IHAs) are accessible, authoritative, illustrated summaries of what we know about specific types of archaeological site, building, landscape or marine asset. Typically they deal with subjects which lack such a summary. This can either be where the literature is dauntingly voluminous, or alternatively where little has been written. Most often it is the latter, and many IHAs bring understanding of site or building types which are neglected or little understood. Many of these are what might be thought of as ‘new heritage’, that is they date from after the Second World War. With origins that can be traced to annual fairs and 18th-century pleasure grounds, and much influenced by America’s Coney Island amusement park of the 1890s, England has one of the finest amusement park and fairground ride heritages in the world. A surprising amount survives today. The most notable site is Blackpool Pleasure Beach, in Lancashire, which has an unrivalled heritage of pre-1939 fairground rides. Other early survivals in England include scenic railways at Margate and Great Yarmouth, and water splash rides in parks at Kettering, Kingston-upon-Hull and Scarborough that date from the 1920s. This guidance note has been written by Allan Brodie and edited by Paul Stamper. It is one is of several guidance documents that can be accessed HistoricEngland.org.uk/listing/selection-criteria/listing-selection/ihas-buildings/ Published by Historic England June 2015. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. HistoricEngland.org.uk/listing/ Front cover A modern aerial photograph of Blackpool Pleasure Beach showing the complex landscape that evolved during the 20th century. -

The History of Sir Hiram Maxim

The History of Sir Hiram Maxim On a small hill overlooking Dexter's Lake Wasookeag on a June day in 1890, a gathering of townspeople watched history in the making as bullets whizzed into the lake waters at a rate of 666 per minute. The small-town quiet was shattered as the gun swayed back and forth to show how a fast-moving army could be cut down in minutes. From that location, about 10 miles from his Sangerville home, Sir Hiram Maxim's gun entered the battlefields of the Russo- Japanese War and later World War I, World War II, and even the battlefields of Korea and Vietnam. As a boy, Hiram Maxim lived at Brockway Mills, located off Silvers Mills Road. Born on the fifth of February, 1840 in a less than modest home - on a small knoll overlooking a stream, he tended sheep throughout the summer months. Legend has it, as a young lad he and his brother Hudson stood atop a large boulder outside their home and with raised arms pledged to themselves that someday they would become famous. Both men achieved fame and garnered themselves a place in the history books. Hiram's only schooling was what he gleaned from five years of learning in a one-room Sangerville schoolhouse. At the age of 14, he was apprenticed to Daniel Sweat, an East Corinth carriage maker who had recently returned to Sangerville. Hiram went to work for Mr. Sweat in Abbott and it was there that he perfected his first invention - an automatic mousetrap that soon rid the Abbot grist mill of mice. -

Lourdes Ortega Curriculum Vitae

Lourdes Ortega Curriculum Vitae Updated: August 2019 Department of Linguistics 1437 37th Street NW Box 571051 Poulton Hall 250 Georgetown University Washington, DC 20057-1051 Department of Linguistics Fax (202) 687-6174 E-mail: [email protected] Webpage: https://sites.google.com/a/georgetown.edu/lourdes-ortega/ EDUCATION 2000 Ph.D. in Second Language Acquisition. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Department of Second Language Studies, USA. 1995 M.A. in English as a Second Language. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Department of Second Language Studies, USA. 1993 R.S.A. Dip., Diploma for Overseas Teachers of English. Cambridge University/UCLES, UK. 1987 Licenciatura in Spanish Philology. University of Cádiz, Spain. EMPLOYMENT since 2012 Professor, Georgetown University, Department of Linguistics. 2004-2012 Professor (2010-2012), Associate Professor (2006-2010), Assistant Professor (2004-2006), University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Department of Second Language Studies. 2002-2004 Assistant Professor (tenure-track), Northern Arizona University, Department of English. 2000-2002 Assistant Professor (tenure-track). Georgia State University, Department of Applied Linguistics and ESL. 1999-2000 Visiting Instructor of Applied Linguistics, Georgetown University, Department of Linguistics. 1994-1998 Research and Teaching Graduate Assistant, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, College of Languages, Linguistics, and Literature. 1987-1993 Instructor of Spanish, Instituto Cervantes of Athens, Greece. FELLOWSHIPS 2018: Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, Advanced Research Collaborative (ARC). August through December, 2018. 2010: External Senior Research Fellow at the Freiburg Institute of Advanced Studies (FRIAS), University of Freiburg. One-semester residential fellowship at FRIAS to carry out project titled Pathways to multicompetence: Applying usage-based and constructionist theories to the study of interlanguage development. -

BAAL News 93

News Number 93 Winter 2009 British Association for Applied Linguistics Registered charity no. 264800 Promoting understanding of language in use. http://www.baal.org.uk THE BRITISH ASSOCIATION FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS Membership Individual Membership is open to anyone qualified or active in applied linguistics. Applied linguists who are not normally resident in Great Britain or Northern Ireland are welcome to join, although they will normally be expected to join their local AILA affiliate in addition to BAAL. Associate Membership is available to publishing houses and to other appropriate bodies at the discretion of the Executive Committee. Institution membership entitles up to three people to be full members of BAAL. Chair (2006-2009) Susan Hunston Department of English University of Birmingham Birmingham B15 2TT email: [email protected] Membership Secretary (2007-2010) Lynn Erler Department of Education University of Oxford 15 Norham Gardens Oxford OX2 6PY [email protected] Membership administration Jeanie Taylor, Administrator c/o Dovetail Management Consultancy PO Box 6688 London SE15 3WB email: [email protected] Editorial Dear all, Welcome to the Autumn/Winter 2009 issue of BAALNews. As always, the Autumn/Winter issue of the BAAL Newsletter is a feature-packed one; so much so, in fact that I will not even try to summarise everything contained within these pages. Instead, I would simply like to draw your attention to the fact that this issue contains the inaugural report of incoming BAAL chair Guy Cook. Guy begins by rightly praising his predecessor, Susan Hunston, for the energy and commitment that she brought to her role, and for her many and various achievements as chair for the period 2006 – 2009. -

Foreign-Language Grammar Instruction Via the Mother Tongue

Paradowski, Michał B. (2007) In: Boers, Frank, Jeroen Darquennes, & Rita Temmerman (eds) Multilingualism and Applied Comparative Linguistics, Vol. 1: Comparative Considerations in Second and Foreign Language Instruction. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press. CHAPTER EIGHT FOREIGN-LANGUAGE GRAMMAR INSTRUCTION VIA THE MOTHER TONGUE MICHAL B. PARADOWSKI Ang hindî marunong lumingón sa pinanggalingan ay hindî makararatíng sa paroroonan [He who does not look back to where he came from will not reach where he is headed] —ancient Tagalog proverb Introduction The overwhelming majority of EFL language course books and grammar reference materials on the market provide English-language explanations and totally ignore the relations holding between the students’ mother tongue (L1) and the target language (TL). Such books are moulded along a generic approach in the sense that they are supposed to cater to the 1 learners’ needs irrespective of their L1. And yet, it is received wisdom that the learner’s L1 has a strong influence on learning another. On the one hand, features of the L1 intrude into learners’ interlanguage (IL). There is ample evidence that particular transfer errors occur in whole populations sharing the same L1, and that certain L1-influenced structures get fossilised in the learners’ IL (Ellis 1994, 337f.). On the other hand, the influence can be advantageous in the sense that language transfer can be turned into a learning strategy when the learner relies on existing knowledge to facilitate new learning. Turning L1 transfer into a strategy, however, requires consciousness-raising, since only those “rules” and structures that the learner is aware of can consciously be transferred (e.g. -

American and German Machine Guns Used in WWI

John Frederick Andrews Novels of the Great War American and German Machine Guns Used in WWI The machine gun changed the face of warfare in WWI. The devastating effects of well-emplaced machine guns against infantry and cavalry became brutally evident in the 1st World War. It changed infantry tactics forever. The US Marines and Army had several machine guns available during the war. This brief will discuss crew-served machine guns only. Man-portable automatic rifles are discussed in another article. The Lewis gun is mentioned here for completeness. The Marine 1st Machine Gun Battalion, commanded by Maj. Edward Cole trained with the Lewis gun before shipping overseas. The gun had been used by the British with good effect. Cole’s men trained with at the Lewis facility in New York. At that point, the plan was for each company to have an eight-gun machine gun platoon. A critical shortage in the aviation community stripped the Marines of their Lewis guns before they shipped to France. The Lewis Gun weighed 28 pounds and was chambered in the .303 British, .30.06 Springfield, and 7.92x57 mm Mauser. They were fed by a top-mounted magazine that could hold 47 or 96 rounds. Rate of fire was 500-600 rounds per minute with a muzzle velocity of 2,440 feet per second and an effective range of 880 yards and a maximum of 3,500 yards. The infantry model is shown below. John Frederick Andrews Novels of the Great War When the Lewis guns were taken away, the Hotchkiss Model 1914 was issued in its place.