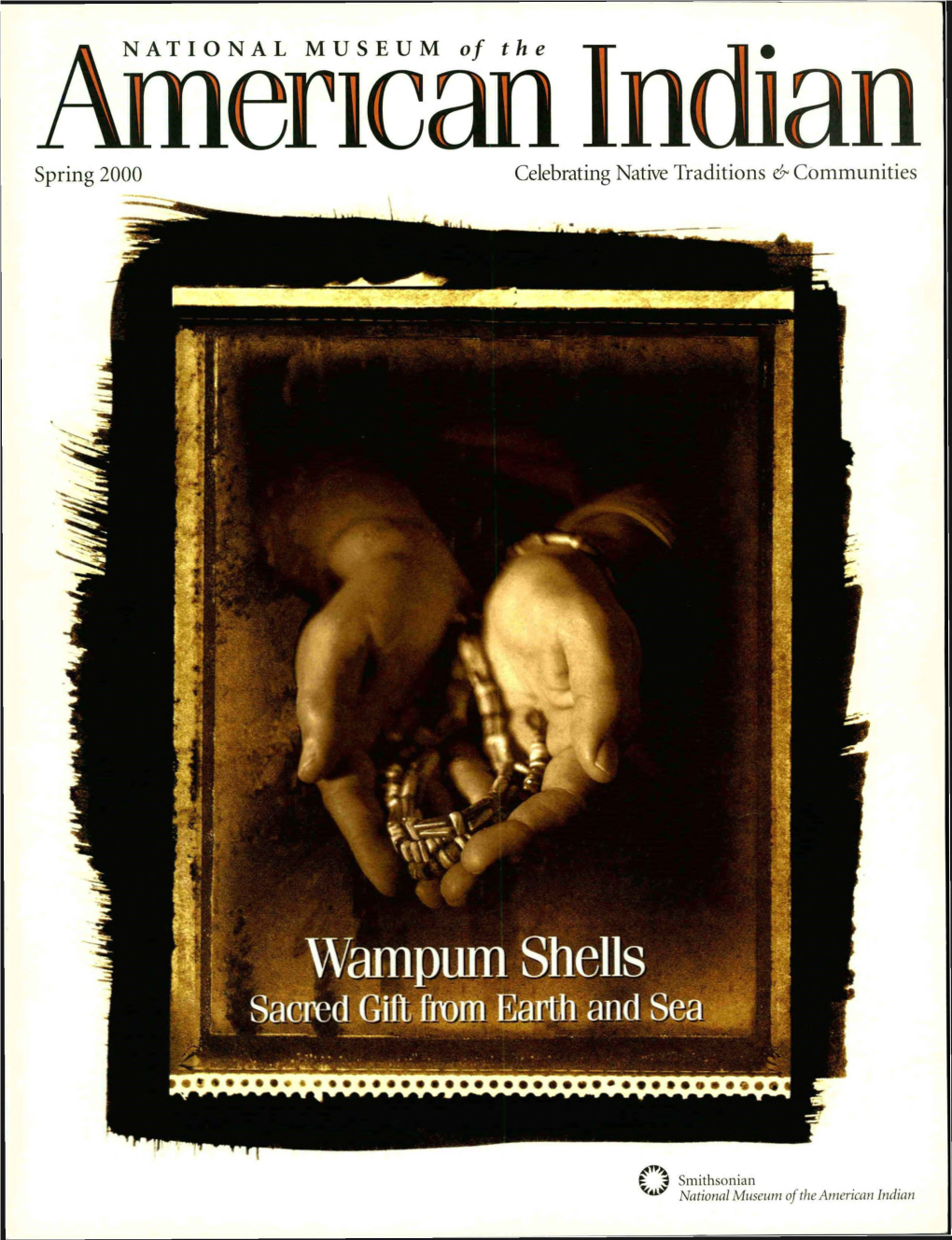

Spring 2000 Celebrating Native Traditions & Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOLLY $2.79 V a Ria B Le Equipment Report Their Sales Booming

PAGE TWENTY-EIGHT-MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD, MamhosUT. Conn Tliuis Ih- ‘>1 l'(7H TV Cuts Down on Shoplifting By L«‘RO^ IMM*K veillance purposes, inuch ol it in discount and con Olson said. I 1*1 liiiKiiiON \\ rilvr venience stores, drugstores, supermarkets and variety There are four basic types of equipment: exposed TV State Employees Pay NEW YORK (UPl) — Television surveillance in retail stores. cameras linked to monitors, satellite systems, Assassination Probe Plans For Glastonbury Heavy Schoolboy stores is starting to make a substantial dent in losses Charles D. Olson of Raleigh. N.C.. president ol "discreet" systems consisting of a mirrored globe con Expected to Continue Raises Uncertain Industrial Park Progresses Slate Here Tonight caused by shoplifting, employee pilferage and loafing by PhotoScan. said it is estimated that in recent years taining a concealed camera and mobile camera systems workers, an association of TV equipment dealers claims. shoplifting and employee thelt have siphoned oft 3 to 5 in which the camera can be moved along a carrier rail. Page 4- Page 5 Page 12 Page 13 The group is PhotoScan Associates. Inc., which is com percent of retail sales in such stores. Estimates from All the systems can be connected to video recorders. The posed of 44 dealers who design, install and sell or lease trade groups are a little lower. video recorder is being used increasingly because it WEEKEND SPECIAL such equipment. The dealers expect their sales of the surveillance ()rovides indisputable evidence for use in court. So successful is the equipment in curbing thelt losses equipment to grow faster than those ol the manulac- In addition to curbing shoplifting and pilferage, the TV that RCA. -

The Cambridge History of American Music - Edited by David Nicholls Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521454298 - The Cambridge History of American Music - Edited by David Nicholls Index More information Index AACM (Association for the Advancement of relationship with Africa 103–112, 114, Creative Musicians) 456–458, 463, 465 115–117, 120–121, 134, 295; stereotypes Abba 343, 368 166–167, 171 (see also minstrelsy); and Abbott, Emma 41 the West Indies 112–113, 115 Abdul, Paula 376 After the Ball 164, 183, 322, 327 Abrams, Muhal Richard 457 Agee, James 486 AC/DC 370 Ainsworth, Henry 35, 82–83 Acadians 151, 295 Ain’t Misbehavin’ 413 accessibility 158–159, 222 Aitken, John 67 accompaniment patterns 314, 321 Alabama (group) 376 accordion 150, 151, 283, 292, 301–302 Aladdin 333 acid house 386 Albert, Stephen 561–562 acid jazz 467 Alboni, Marietta 203 acid rock 347–348, 363 Alexander, James 76, 77 Acu◊, Roy 356 Alexander’s Ragtime Band 393–394 Adam, Adolphe 202 Alice Cooper 371 Adams, Abraham 92 All I Want Is a Room Somewhere 321 Adams, John (18th-century) 69, 186 All Quiet Along the Potomac Tonight 182 Adams, John (20th-century) 260, 557–558 Allen, Red 429 Adderley, Julian “Cannonball” 447 Allen, Richard 81, 120, 127 Addison, Joseph 70 Allen, Woody 532 Adgate, Andrew 66–67 Allman Brothers Band, the 369 Adler, Richard 341 alternative music 381–383 Adorno, Theodore 324 alternative rock 266, 347–348 advertising jingles 314, 336, 337 amateur music 189–190, 193; amateurs and Aerosmith 370 professionals performing together 66, AFM (American Federation of Musicians) 189, 216–217 349–350 ambient music 386 Africa, music in -

OCR Document

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 14, No. 5 (1992) Hail to the real ‘redskins’ All Indian team from Hominy, Okla. , took on all comers By Arthur Shoemaker Buried deep in the dusty files of the Hominy ( Okla. ) News is this account of a professional football game between the Avant Roughnecks and the Hominy Indians played in October 1924: “Johnnie Martin, former pitcher for the Guthrie team of the Oklahoma State League, entered the game in the fourth quarter. On the first play, Martin skirted right end for a gain of 20 yards. However, Hominy was penalized 15 yards for Martin having failed to report to the referee. On the next three plays, the backfield hit the line for a first down. With the ball on the 20-yard line, Martin again skirted right end for the winning touchdown.” This speedy, high-stepping halfback was none other than Pepper Martin, star third baseman of the St. Louis Cardinals’ “Gas House Gang” of the 1930s. Pepper became famous during the 1931 World Series when the brash young Cardinals beat the star- studded Philadelphia Athletics four games to three. Nowhere is Pepper more fondly remembered than in the land of the Osage. For all his fame as a baseball star, he’s best remembered as a spectacular hard-running halfback on Oklahoma’s most famous and most colorful professional football team, the Hominy Indians. It was here that Pepper was called the “Wild Horse of the Osage.” The football team was organized in late 1923 at a time when Hominy was riding the crest of the fantastic Osage oil boom. -

National Football League Franchise Transactions

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 4 (1982) The following article was originally published in PFRA's 1982 Annual and has long been out of print. Because of numerous requests, we reprint it here. Some small changes in wording have been made to reflect new information discovered since this article's original publication. NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE FRANCHISE TRANSACTIONS By Joe Horrigan The following is a chronological presentation of the franchise transactions of the National Football League from 1920 until 1949. The study begins with the first league organizational meeting held on August 20, 1920 and ends at the January 21, 1949 league meeting. The purpose of the study is to present the date when each N.F.L. franchise was granted, the various transactions that took place during its membership years, and the date at which it was no longer considered a league member. The study is presented in a yearly format with three sections for each year. The sections are: the Franchise and Team lists section, the Transaction Date section, and the Transaction Notes section. The Franchise and Team lists section lists the franchises and teams that were at some point during that year operating as league members. A comparison of the two lists will show that not all N.F.L. franchises fielded N.F.L. teams at all times. The Transaction Dates section provides the appropriate date at which a franchise transaction took place. Only those transactions that can be date-verified will be listed in this section. An asterisk preceding a franchise name in the Franchise list refers the reader to the Transaction Dates section for the appropriate information. -

Use of Native American Team Names in the Formative Era of American Sports, 1857-1933

BEFORE THE REDSKINS WERE THE REDSKINS: THE USE OF NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES IN THE FORMATIVE ERA OF AMERICAN SPORTS, 1857-1933 J. GORDON HYLTON* L INTRODUCTION 879 IL CURRENT SENTIMENT 881 III. A BRIEF HISTORY OF NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES 886 IV. THE FIRST USAGES OF NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES IN AMERICAN SPORT 890 A. NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES IN EARLY BASEBALL .... 891 B. NATIVE AMERICAN TEAMS NAMES IN EARLY PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL 894 C. NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES IN COLLEGE SPORT 900 V. CONCLUSION 901 I. INTRODUCTION The Native American team name and mascot controversy has dismpted the world of American sports for more than six decades. In the 1940s, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) began a campaign against a variety of negative and unfiattering stereotypes of Indians in American culture.' Over time, the campaign began to focus on the use of Native American team names—like Indians and Redskins—and mascots by college and professional sports teams.2 The NCAI's basic argument was that the use of such names, mascots, and logos was offensive and *J. Gordon Hylton is Professor of Law at Marquette University and Visiting Professor of Law at the University of Virginia. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and the University of Virginia Law School and holds a PhD in the History of American Civilization from Harvard. From 1997 to 1999, he was Director ofthe National Sports Law Institute and is the current Chair-Elect ofthe Association of American Law Schools Section on Law and Sport. 1. See Our History, NCAI, http://www.ncai.Org/Our-History.14.0.html (last visited Apr. -

2014 Panther Football

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Athletics Media Guides Athletics 2014 2014 Panther Football University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1992 Athletics, University of Northern Iowa Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/amg Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation University of Northern Iowa, "2014 Panther Football" (2014). Athletics Media Guides. 231. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/amg/231 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Athletics Media Guides by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2014 UNI FOOTBALL GENERAL FACTS 2014 SCHEDULE School .....................................University of Northern Iowa Date Opponent Site Time Founded ....................................................................... 1876 Enrollment ................................................................. 12,159 Aug. 30 Iowa Iowa City, Iowa 11 a.m. Nickname ...............................................................Panthers Sep. 6 OPEN Colors .................................................Purple and Old Gold Sep. 13 Hawai’i Honolulu, Hawai’i 11 p.m. Stadium ............................................................... UNI-Dome Sep. 20 Northern Colorado UNI-Dome 4 p.m. Capacity .................................................................... 16,324 Affiliation .........................................NCAA -

A NATIONAL MUSEUM of the Summer 2000 Celebrating Native

AmencanA NATIONAL MUSEUM of the Indiant ~ti • Summer 2000 Celebrating Native Traditions & Communities INDIAN JOURNALISM • THE JOHN WAYNE CLY STORY • COYOTE ON THE POWWOW TRAIL t 1 Smithsonian ^ National Museum of the American Indian DAVID S AIT Y JEWELRY 3s P I! t£ ' A A :% .p^i t* A LJ The largest and bestfôfltikfyi of Native American jewelry in the country, somçjmhem museum quality, featuring never-before-seen immrpieces of Hopi, Zuni and Navajo amsans. This collection has been featured in every major media including Vogue, Elle, Glamour, rr_ Harper’s Bazaar, Mirabella, •f Arnica, Mademoiselle, W V> Smithsonian Magazine, SHBSF - Th'NwYork N ± 1R6%V DIScbuNTDISCOUNT ^ WC ^ 450 Park Ave >XW\0 MEMBERS------------- AND television stations (bet. 56th/57th Sts) ' SUPPORTERS OF THE nationwide. 212.223.8125 NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE © CONTENTS Volume 1, Number 3, Summer 2000 10 Read\ tor Pa^JG One -MarkTrahantdescribeshowIndianjoumalistsHkeMattKelley, Kara Briggs, and Jodi Rave make a difference in today's newsrooms. Trahant says today's Native journalists build on the tradition of storytelling that began with Elias Boudinot, founder of the 19th century newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. 1 ^ WOVCn I hrOU^h Slone - Ben Winton describes how a man from Bolivia uses stone to connect with Seneca people in upstate New York. Stone has spiritual and utilitarian significance to indigeneous cultures across the Western Hemisphere. Roberto Ysais photographs Jose Montano and people from the Tonawanda Seneca Nation as they meet in upstate New York to build an apacheta, a Qulla cultural icon. 18 1 tie John Wayne Gly Story - John Wayne Cly's dream came true when he found his family after more than 40 years of separation. -

The Use of Native American Team Names in the Formative Era of American Sports, 1857-1933

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UND Scholarly Commons (University of North Dakota) North Dakota Law Review Volume 86 Number 4 Article 7 1-1-2010 Before the Redskins Were the Redskins: The Use of Native American Team Names in the Formative Era of American Sports, 1857-1933 J. Gordon Hylton Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hylton, J. Gordon (2010) "Before the Redskins Were the Redskins: The Use of Native American Team Names in the Formative Era of American Sports, 1857-1933," North Dakota Law Review: Vol. 86 : No. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://commons.und.edu/ndlr/vol86/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Dakota Law Review by an authorized editor of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEFORE THE REDSKINS WERE THE REDSKINS: THE USE OF NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES IN THE FORMATIVE ERA OF AMERICAN SPORTS, 1857-1933 J. GORDON HYLTON* I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 879 II. CURRENT SENTIMENT .......................................................... 881 III. A BRIEF HISTORY OF NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES ....................................................................................... 886 IV. THE FIRST USAGES OF NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES IN AMERICAN SPORT .............................................. 890 A. NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES IN EARLY BASEBALL .... 891 B. NATIVE AMERICAN TEAMS NAMES IN EARLY PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL ................................................... 894 C. NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES IN COLLEGE SPORT ....... 900 V. CONCLUSION .......................................................................... -

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org $4.00 TABLE OF CONTENTS Historical Background 03 Trails and Settlements 03 Shelters and Dwellings 04 Clothing and Dress 07 Arts and Crafts 08 Religions 09 Medicine 10 Agriculture, Hunting, and Fishing 11 The Fur Trade 12 Five Major Tribes of Ohio 13 Adapting Each Other’s Ways 16 Removal of the American Indian 18 Ohio Historical Society Indian Sites 20 Ohio Historical Marker Sites 20 Timeline 32 Glossary 36 The Ohio Historical Society 1982 Velma Avenue Columbus, OH 43211 2 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio HISTORICAL BACKGROUND In Ohio, the last of the prehistoric Indians, the Erie and the Fort Ancient people, were destroyed or driven away by the Iroquois about 1655. Some ethnologists believe the Shawnee descended from the Fort Ancient people. The Shawnees were wanderers, who lived in many places in the south. They became associated closely with the Delaware in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Able fighters, the Shawnees stubbornly resisted white pressures until the Treaty of Greene Ville in 1795. At the time of the arrival of the European explorers on the shores of the North American continent, the American Indians were living in a network of highly developed cultures. Each group lived in similar housing, wore similar clothing, ate similar food, and enjoyed similar tribal life. In the geographical northeastern part of North America, the principal American Indian tribes were: Abittibi, Abenaki, Algonquin, Beothuk, Cayuga, Chippewa, Delaware, Eastern Cree, Erie, Forest Potawatomi, Huron, Iroquois, Illinois, Kickapoo, Mohicans, Maliseet, Massachusetts, Menominee, Miami, Micmac, Mississauga, Mohawk, Montagnais, Munsee, Muskekowug, Nanticoke, Narragansett, Naskapi, Neutral, Nipissing, Ojibwa, Oneida, Onondaga, Ottawa, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Peoria, Pequot, Piankashaw, Prairie Potawatomi, Sauk-Fox, Seneca, Susquehanna, Swamp-Cree, Tuscarora, Winnebago, and Wyandot. -

Chapter Eight

CHAPTER EIGHT PRO FOOTBALL’S EARLY YEARS Then all of a sudden this team was playing to 6,000–8,000 people. I personally think that the Oorang Indians, the Canton Bulldogs, and the Massillon Tigers were three teams that probably introduced people to pro football. — Robert Whitman. Professional football got its start long after pro baseball, and for many years was largely ignored by the general public. Prior to 1915, when Jim Thorpe signed with the Canton Bulldogs, there was little money in the game. The players earned less than was paid, under the table, to some allegedly amateur players on success- ful college teams. Jim Thorpe, 1920s jim thorpe association Things changed when Thorpe entered the pro game. Jack Cusack, the manager of the Canton Bulldogs, recalled: “I hit the jackpot by signing the famous Jim Thorpe … some of my business ‘advisers’ frankly predicted that I was leading the Bulldogs into bankruptcy by paying Jim the enormous sum of $250 a game, but the deal paid off even beyond my greatest expectations. Jim was an attraction as well as a player. Whereas our paid attendance averaged about 1,200 before we took him on, we filled the Massil- lon and Canton parks for the next two games — 6,000 for the first and 8,000 for the second. All the fans wanted to see the big Indian in action. On the field, Jim was a fierce competitor, absolutely fearless. Off the field, he was a lovable fellow, big-hearted and with a good sense of humor.” Unlike Thorpe’s experience in professional baseball, he was fully utilized on the gridiron as a running back, kicker, and fierce defensive player. -

Tribute to Charlie Conerly

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 18, No. 6 (1996) TRIBUTE TO CHARLIE CONERLY By Jimmie G. Purvis Charlie Conerly, who was the starting quarterback of the New York Giants during most of the 1950s, died on February 13, 1996 at the age of 74. His death re-sulted from complications growing out of heart bypass surgery performed several months earlier. A steady signal caller, Conerly played in the NFL for fourteen years (1948-1961) and led the Giants to three divisional titles and one championshipship. In 1959 the graying, thirty- eight-year-old veteran was recognized as the MVP of the league and received the Jim Thorpe Trophy. Conerly had perhaps the finest season of his long and distinguished career. He completed 58 per cent of his passes for 1,706 yards and 14 touchdowns. Y.A. Tittle, acquired in a trade with the San Francisco 49ers, replaced the ex- Marine in 1961 and passed the Giants into the NFL title game against the Green Bay Packers. However, even in the twilight of his playing days Conerly still possessed the ability to come off the bench and rally the struggling New Yorkers to key victories over the Los Angeles Rams and Philadelphia Eagles. With those two valuable contributions, he brought to a close in a fitting fashion a lengthy run as a dependable performer whose greatest qualities were consistency and physical and mental toughness. Conerly came to the Giants in 1948 from the University of Mississippi where he had established himself as one of the top passers in the Southeastern Conference. -

2016 Gsc Football Record Book

2016 GSC FOOTBALL RECORD BOOK GSC Contact Information MAILING ADDRESS Gulf South Conference 2101 Providence Park; Suite 200 Birmingham, AL 35242 PHONE NUMBER -- FAX NUMBER (205) 991-9880 -- (205) 437-0505 GSC WEBSITE -- www.gscsports.org FACEBOOK -- The Gulf South Conference TWITTER -- @GulfSouth INSTAGRAM -- gscsports GSC Staff COMMISSIONER Matt Wilson E-mail: [email protected] CHAIR OF THE PRESIDENTS Dr. William LaForge, Delta State ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER/COMPLIANCE Andrea Anderson E-mail: [email protected] ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER/CHAMPIONSHIPS Michael Anderson E-mail: [email protected] Table of Contents GSC History Page ............................................................................................................................. 1 ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER/SPORTS INFO. GSC Football History .................................................................................................................. 2-46 GSC Annual Team and Individual Statistical Leaders ...................................................... 2-8 Nick Moeller GSC Annual Standings ................................................................................................... 9-13 E-mail: [email protected] GSC in the NCAA Division II Playoffs and Results ....................................................... 14-16 GSC-TV Game of the Week .............................................................................................. 17 DIRECTOR OF ENGAGEMENT All-Time All-GSC Teams ..............................................................................................