The Oorang Indians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCR Document

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 14, No. 5 (1992) Hail to the real ‘redskins’ All Indian team from Hominy, Okla. , took on all comers By Arthur Shoemaker Buried deep in the dusty files of the Hominy ( Okla. ) News is this account of a professional football game between the Avant Roughnecks and the Hominy Indians played in October 1924: “Johnnie Martin, former pitcher for the Guthrie team of the Oklahoma State League, entered the game in the fourth quarter. On the first play, Martin skirted right end for a gain of 20 yards. However, Hominy was penalized 15 yards for Martin having failed to report to the referee. On the next three plays, the backfield hit the line for a first down. With the ball on the 20-yard line, Martin again skirted right end for the winning touchdown.” This speedy, high-stepping halfback was none other than Pepper Martin, star third baseman of the St. Louis Cardinals’ “Gas House Gang” of the 1930s. Pepper became famous during the 1931 World Series when the brash young Cardinals beat the star- studded Philadelphia Athletics four games to three. Nowhere is Pepper more fondly remembered than in the land of the Osage. For all his fame as a baseball star, he’s best remembered as a spectacular hard-running halfback on Oklahoma’s most famous and most colorful professional football team, the Hominy Indians. It was here that Pepper was called the “Wild Horse of the Osage.” The football team was organized in late 1923 at a time when Hominy was riding the crest of the fantastic Osage oil boom. -

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 7, No. 5 (1985) THE 1920s ALL-PROS IN RETROSPECT By Bob Carroll Arguments over who was the best tackle – quarterback – placekicker – water boy – will never cease. Nor should they. They're half the fun. But those that try to rank a player in the 1980s against one from the 1940s border on the absurd. Different conditions produce different results. The game is different in 1985 from that played even in 1970. Nevertheless, you'd think we could reach some kind of agreement as to the best players of a given decade. Well, you'd also think we could conquer the common cold. Conditions change quite a bit even in a ten-year span. Pro football grew up a lot in the 1920s. All things considered, it's probably safe to say the quality of play was better in 1929 than in 1920, but don't bet the mortgage. The most-widely published attempt to identify the best players of the 1920s was that chosen by the Pro Football Hall of Fame Selection Committee in celebration of the NFL's first 50 years. They selected the following 18-man roster: E: Guy Chamberlin C: George Trafton Lavie Dilweg B: Jim Conzelman George Halas Paddy Driscoll T: Ed Healey Red Grange Wilbur Henry Joe Guyon Cal Hubbard Curly Lambeau Steve Owen Ernie Nevers G: Hunk Anderson Jim Thorpe Walt Kiesling Mike Michalske Three things about this roster are striking. First, the selectors leaned heavily on men already enshrined in the Hall of Fame. There's logic to that, of course, but the scary part is that it looks like they didn't do much original research. -

Eagles' Team Travel

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2019-2020 EDITIOn PHILADELPHIA EAGLES Team History The Eagles have been a Philadelphia institution since their beginning in 1933 when a syndicate headed by the late Bert Bell and Lud Wray purchased the former Frankford Yellowjackets franchise for $2,500. In 1941, a unique swap took place between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh that saw the clubs trade home cities with Alexis Thompson becoming the Eagles owner. In 1943, the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh franchises combined for one season due to the manpower shortage created by World War II. The team was called both Phil-Pitt and the Steagles. Greasy Neale of the Eagles and Walt Kiesling of the Steelers were co-coaches and the team finished 5-4-1. Counting the 1943 season, Neale coached the Eagles for 10 seasons and he led them to their first significant successes in the NFL. Paced by such future Pro Football Hall of Fame members as running back Steve Van Buren, center-linebacker Alex Wojciechowicz, end Pete Pihos and beginning in 1949, center-linebacker Chuck Bednarik, the Eagles dominated the league for six seasons. They finished second in the NFL Eastern division in 1944, 1945 and 1946, won the division title in 1947 and then scored successive shutout victories in the 1948 and 1949 championship games. A rash of injuries ended Philadelphia’s era of domination and, by 1958, the Eagles had fallen to last place in their division. That year, however, saw the start of a rebuilding program by a new coach, Buck Shaw, and the addition of quarterback Norm Van Brocklin in a trade with the Los Angeles Rams. -

National Football League Franchise Transactions

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 4 (1982) The following article was originally published in PFRA's 1982 Annual and has long been out of print. Because of numerous requests, we reprint it here. Some small changes in wording have been made to reflect new information discovered since this article's original publication. NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE FRANCHISE TRANSACTIONS By Joe Horrigan The following is a chronological presentation of the franchise transactions of the National Football League from 1920 until 1949. The study begins with the first league organizational meeting held on August 20, 1920 and ends at the January 21, 1949 league meeting. The purpose of the study is to present the date when each N.F.L. franchise was granted, the various transactions that took place during its membership years, and the date at which it was no longer considered a league member. The study is presented in a yearly format with three sections for each year. The sections are: the Franchise and Team lists section, the Transaction Date section, and the Transaction Notes section. The Franchise and Team lists section lists the franchises and teams that were at some point during that year operating as league members. A comparison of the two lists will show that not all N.F.L. franchises fielded N.F.L. teams at all times. The Transaction Dates section provides the appropriate date at which a franchise transaction took place. Only those transactions that can be date-verified will be listed in this section. An asterisk preceding a franchise name in the Franchise list refers the reader to the Transaction Dates section for the appropriate information. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

1920 Akron Pros Ken Crippen

Building a Champion: 1920 Akron Pros Ken Crippen BUILDING A CHAMPION: 1920 AKRON PROS By Ken Crippen It’s time to dig deep into the archives to talk about the first National Football League (NFL) champion. In fact, the 1920 Akron Pros were champions before the NFL was called the NFL. In 1920, the American Professional Football Association was formed and started play. Currently, fourteen teams are included in the league standings, but it is unclear as to how many were official members of the Association. Different from today’s game, the champion was not determined on the field, but during a vote at a league meeting. Championship games did not start until 1932. Also, there were no set schedules. Teams could extend their season in order to try and gain wins to influence voting the following spring. These late-season games were usually against lesser opponents in order to pad their win totals. To discuss the Akron Pros, we must first travel back to the century’s first decade. Starting in 1908 as the semi-pro Akron Indians, the team immediately took the city championship and stayed as consistently one of the best teams in the area. In 1912, “Peggy” Parratt was brought in to coach the team. George Watson “Peggy” Parratt was a three-time All-Ohio football player for Case Western University. While in college, he played professionally for the 1905 Shelby Blues under the name “Jimmy Murphy,” in order to preserve his amateur status. It only lasted a few weeks until local reporters discovered that it was Parratt on the field for the Blues. -

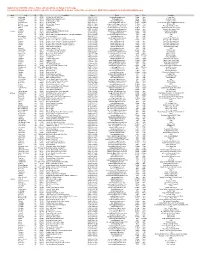

PHR Local Website Update 4-25-08

Updated as of 4/25/08 - Dates, Times and Locations are Subject to Change For more information or to confirm a specific local competition, please contact the Local Host or MLB PHR Headquarters at [email protected] State City ST Zip Local Host Phone Email Date Time Location Alaska Anchorage AK 99508 Mt View Boys & Girls Club (907) 297-5416 [email protected] 22-Apr 4pm Lions Park Anchorage AK 99516 Alaska Quakes Baseball Club (907) 344-2832 [email protected] 3-May Noon Kosinski Fields Cordova AK 99574 Cordova Little League (907) 424-3147 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Volunteer Park Delta Junction AK 99737 Delta Baseball (907) 895-9878 [email protected] 6-May 4:30pm Delta Junction City Park HS Baseball Field Eielson AK 99702 Eielson Youth Program (907) 377-1069 [email protected] 17-May 11am Eielson AFB Elmendorf AFB AK 99506 3 SVS/SVYY (907) 868-4781 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Elmendorf Air Force Base Nikiski AK 99635 NPRSA 907-776-8800x29 [email protected] 10-May 10am Nikiski North Star Elementary Seward AK 99664 Seward Parks & Rec (907) 224-4054 [email protected] 10-May 1pm Seward Little League Field Alabama Anniston AL 36201 Wellborn Baseball Softball for Youth (256) 283-0585 [email protected] 5-Apr 10am Wellborn Sportsplex Atmore AL 36052 Atmore Area YMCA (251) 368-9622 [email protected] 12-Apr 11am Atmore Area YMCA Atmore AL 36502 Atmore Babe Ruth Baseball/Atmore Cal Ripken Baseball (251) 368-4644 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD Birmingham AL 35211 AG Gaston -

An Examination of the Effects of Financing Structure on Football Facility Design and Surrounding Real Estate Development

Field$ of Dream$: An Examination of the Effects of Financing Structure on Football Facility Design and Surrounding Real Estate Development by Aubrey E. Cannuscio B.S., Business Administration, 1991 University of New Hampshire Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1997 @1997 Aubrey E. Cannuscio All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Departme of-Urban Studies and Planning August 1, 1997 Certified by: Timothy Riddiough A sistant Professor of Real Estate Finance Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: William C. Wheaton Chairman, Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development a'p) Field$ of Dream$: An Examination of the Effects of Financing Structure on Football Facility Design and Surrounding Real Estate Development by Aubrey E. Cannuscio Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on August 1, 1997 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development ABSTRACT The development of sports facilities comprises a large percentage of municipal investment in infrastructure and real estate. This thesis will analyze, both quantitatively and qualitatively, all football stadiums constructed in the past ten years and how their design, financing and siting impact the surrounding real estate market. The early chapters of this thesis cover general trends and issues in financing, design and development of sports facilities. -

BUFFALO BILLS Team History

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2020-2021 EDITIOn QUARTERBACK JIM KELLY - hall of fame class of 2002 BUFFALO BILLS Team History The Buffalo Bills began their pro football life as the seventh team to be admitted into the new American Football League. The franchise was awarded to Ralph C. Wilson on October 28, 1959. Since that time, the Bills have experienced extended periods of both championship dominance and second-division frustration. The Bills’ first brush with success came in their fourth season in 1963 when they tied for the AFL Eastern division crown but lost to the Boston Patriots in a playoff. In 1964 and 1965 however, they not only won their division but defeated the San Diego Chargers each year for the AFL championship. Head Coach Lou Saban, who was named AFL Coach of the Year each year, departed after the 1965 season. Buffalo lost to the Kansas City Chiefs in the 1966 AFL title game and, in doing so, just missed playing in the first Super Bowl. Then the Bills sank to the depths, winning only 13 games while losing 55 and tying two in the next five seasons. Saban returned in 1972, utilized the Bills’ superstar running back, O. J. Simpson, to the fullest extent and made the Bills competitive once again. That period was highlighted by the 2,003-yard rushing record set by Simpson in 1973. But Saban departed in mid-season 1976 and the Bills again sank into the second division until a new coach, Chuck Knox, brought them an AFC Eastern division title in 1980. -

Ben Lee Boynton:The Purple Streak

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 25, No. 3 (2003) Ben Lee Boynton:The Purple Streak by Jeffrey Miller The 1924 season was one of transition for Buffalo’s pro football team. The All-Americans, as the team had been known since its founding in 1920, had been very successful in its four year history, finishing within one game of the league championship in both the 1920 and 1921 seasons. But successive 5-4 campaigns and declining attendance had convinced owner Frank McNeil that it was time to get out of the football business. McNeil sold the franchise to a group led by local businessman Warren D. Patterson and Tommy Hughitt, the team’s player/coach, for $50,000. The new ownership changed the name of the team to Bisons, and committed themselves signing big name players in an effort to improve performance both on the field and at the box office. The biggest transaction of the off-season was the signing of “the Purple Streak,” former Williams College star quarterback Benny Lee Boynton. Boynton, a multiple All America selection at Williams, began his pro career with the Rochester Jeffersons in 1921. His signing with the Bisons in 1924 gave the Buffalo team its first legitimate star since Elmer Oliphant donned an orange and black sweater three years earlier. Born Benjamin Lee Boynton on December 6, 1898 in Waco, Texas, to Charles and Laura Boynton, Ben Lee learned his love of football at an early age. He entered Waco High School in 1912, and the next year began a string of three consecutive seasons and Waco’s starting quarterback. -

2017 National College Football Awards Association Master Calendar

2017 National College Football 9/20/2017 1:58:08 PM Awards Association Master Calendar Award ...................................................Watch List Semifinalists Finalists Winner Banquet/Presentation Bednarik Award .................................July 10 Oct. 30 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] March 9, 2018 (Atlantic City, N.J.) Biletnikoff Award ...............................July 18 Nov. 13 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Feb. 10, 2018 (Tallahassee, Fla.) Bronko Nagurski Trophy ...................July 13 Nov. 16 Dec. 4 Dec. 4 (Charlotte) Broyles Award .................................... Nov. 21 Nov. 27 Dec. 5 [RCS] Dec. 5 (Little Rock, Ark.) Butkus Award .....................................July 17 Oct. 30 Nov. 20 Dec. 5 Dec. 5 (Winner’s Campus) Davey O’Brien Award ........................July 19 Nov. 7 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Feb. 19, 2018 (Fort Worth) Disney Sports Spirit Award .............. Dec. 7 [THDA] Dec. 7 (Atlanta) Doak Walker Award ..........................July 20 Nov. 15 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Feb. 16, 2018 (Dallas) Eddie Robinson Award ...................... Dec. 5 Dec. 14 Jan. 6, 2018 (Atlanta) Gene Stallings Award ....................... May 2018 (Dallas) George Munger Award ..................... Nov. 16 Dec. 11 Dec. 27 March 9, 2018 (Atlantic City, N.J.) Heisman Trophy .................................. Dec. 4 Dec. 9 [ESPN] Dec. 10 (New York) John Mackey Award .........................July 11 Nov. 14 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [RCS] TBA Lou Groza Award ................................July 12 Nov. 2 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Dec. 4 (West Palm Beach, Fla.) Maxwell Award .................................July 10 Oct. 30 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] March 9, 2018 (Atlantic City, N.J.) Outland Trophy ....................................July 13 Nov. 15 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Jan. 10, 2018 (Omaha) Paul Hornung Award .........................July 17 Nov. 9 Dec. 6 TBA (Louisville) Paycom Jim Thorpe Award ..............July 14 Oct. -

NFL 1926 in Theory & Practice

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 24, No. 3 (2002) One division, no playoffs, no championship game. Was there ANY organization to pro football before 1933? Forget the official history for a moment, put on your leather thinking cap, and consider the possibilities of NFL 1926 in Theory and Practice By Mark L. Ford 1926 and 2001 The year 1926 makes an interesting study. For one thing, it was 75 years earlier than the just completed season. More importantly, 1926, like 2001, saw thirty-one pro football teams in competition. The NFL had a record 22 clubs, and Red Grange’s manager had organized the new 9 team American Football League. Besides the Chicago Bears, Green Bay Packers and New York Giants, and the Cardinals (who would not move from Chicago until 1959), there were other team names that would be familiar today – Buccaneers (Los Angeles), Lions (Brooklyn), Cowboys (Kansas City) and Panthers (Detroit). The AFL created rivals in major cities, with American League Yankees to match the National League Giants, a pre-NBA Chicago Bulls to match the Bears, Philadelphia Quakers against the Philly-suburb Frankford Yellowjackets, a Brooklyn rival formed around the two of the Four Horsemen turned pro, and another “Los Angeles” team. The official summary of 1926 might look chaotic and unorganized – 22 teams grouped in one division in a hodgepodge of large cities and small towns, and is summarized as “Frankford, Chicago Bears, Pottsville, Kansas City, Green Bay, Los Angeles, New York, Duluth, Buffalo, Chicago Cardinals, Providence, Detroit, Hartford, Brooklyn, Milwaukee, Akron, Dayton, Racine, Columbus, Canton, Hammond, Louisville”.