Wines We Import

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CULLEN WINES Margaret River, Western Australia

CULLEN WINES Margaret River, Western Australia “Vanya Cullen spearheaded a movement to biodynamic viticulture. She feels the wines are more complete than before. Indeed, today, they are well-calibrated, precise and focused.” - Erik Asimov, New York Times, 2019 Vanya Cullen OWNER: The Cullen Family VINEYARD: Biodynamically farmed and dry-grown FOUNDED: 1971 by Kevin & Diana Cullen SOILS: Granite and gravelly sandy loam over lateritic subsoils WINEMAKER: Vanya Cullen VARIETIES Cullen Vineyards: Cabernet Sauvignon SIZE: 69 acres PLANTED: (28.0 acres), Chardonnay (18.4 acres), Sauvignon Blanc (13.6 acres), Merlot (3.2 acres), Semillon (2.8 acres), Pinot Noir HARVEST: End February to late April (2.3 acres), Cabernet Franc (1.0 acres). Mangan Vineyard: Petit Verdot (13.4 CLIMATE: Mediterranean acres), Sauvignon Blanc (11.9 acres), Semillon (9.8 acres), Merlot (7.6 acres), ANNUAL 45 inches Malbec (6.2 acres). RAINFALL: WEBSITE: www.cullenwines.com.au PerthPerth AUSTRALIA MARGARET RIVER MARGARET RIVER The Cullen vineyard, situated just two miles from the Indian Ocean PROFILE: A founding winery of Margaret River, Cullen Wines VITICULTURE: The Cullen vineyard is one of Margaret was established in 1971 by pioneering winemakers Kevin and River’s greatest viticultural sites. Carefully selected by Diana Cullen. In redefining the style of Australian Cabernet founders Kevin and Diana Cullen, the well-draining, gravelly Sauvignon produced in the 1970s, the fledgling estate soils are complemented by a maritime climate of warm, sun- caught the attention of the nation. Since then, an unrelenting filled days tempered by the surrounding Indian and Southern commitment to quality, integrity, and biodynamics has oceans. -

2020 Wine Enthusiast Buying Guide

BUYINGGUIDE MAY2020 THIS MONTH 2 NEW ZEALAND 25 CHILE 30 URUGUAY 33 OTHER SOUTH AMERICA 33 PORTUGAL 44 ALSACE 54 BORDEAUX 61 SOUTHERN FRANCE 71 TUSCANY 82 CALIFORNIA 113 WASHINGTON 116 SPIRITS 118 BEER Sunrise in the vineyard at Hawkes Bay, North Island, New Zealand FOR ADDITIONAL RATINGS AND REVIEWS, VISIT WINEMAG.COM/RATINGS STEVE FLEMING/GETTY IMAGES FLEMING/GETTY STEVE WINEMAG.COM | 1 BUYINGGUIDE the fruit and spice. While just starting to show some age, this remains an austere but laser-focused wine that requires patience, but should reward in spades with time in cellar. Drink 2021–2035. Wine Dogs Imports LLC. Cellar Selection. —C.P. NEW ZEALAND abv: 13.5% Price: $62 Explore the diversity of Kiwi reds Seresin 2014 Raupo Creek Single Vineyard Pinot Noir (Marlborough). This single-vine- auvignon Blanc may be New Zealand’s warmer North Island, in the clay-dominant 94 yard wine from well respected biodynamic producer calling card, but a slew of red wines add to soils of Auckland, but primarily in Hawke’s Seresin (which has recently been majorly down- the diversity this pair of sea swept islands Bay, where the variety has a nearly 200-year sized, so relish these older vintages while they’re has to offer. history. There are several mineral driven, mus- still here) from the clay slopes of Marlborough’s SWhen it comes to Kiwi reds, Pinot Noir is cular, laser-focused Syrahs from the unique Omaka Valley, is hard not to fall head over heels for. It fills the nose with a perfume of ripe cher- king. -

A7uzegz3tyoaeqzaim23 Jan 2020 Wine Menu. PRINT.Pdf

WINES BY THE GLASS SPARKLING Prosecco is style of wine as well as a recognized appellation Franciacorta, Italy’s answer to Champagne, was one of the country’s First wine regions to be recognized as D.O.C. Established in 1743 by Claude Moët WHITE The Cascina Maiolo farm was founded in 1710 Pinot Grigio is referred to as Pinot Gris in Alsace and the US This unoaked Chardonnay has fresh notes of apple and melon This fragrant wine has notes of acacia, peach, apricot, and citrus As homage to sister property, the caves at CADE Estate are carved in the shape of PlumpJack’s sheild Hand Crafted Cocktails Specialty Cocktails at Quality Italian have been created by Head Barman Bryan Schneider Conceived by two somms in the alley behind Spago Beverly Hills Grey Goose, St. Germain, Cucumber & Basil Angel’s Envy Bourbon, Peach Street Distillers Peach Brandy, Rosé Fresh Lemon & Barolo Float A smoke tree turns a smoky pink-purple shade from June to August Prosecco, Fresh-Pressed Grapefruit, Aperol & Pomegranate Molasses Bulliet Bourbon, Leopold Bros Aperitivo Maraschino & House Vermouth RED Espolon Blanco, Fresh Lime, Calabrian Chili-Infused Honey, This Noble Italian grape is known for its ripe fruit and white pepper notes Served Over A Tricolore Cube Vietti’s wine labels feature original artwork that reflect each vintage COCKTAILS ON DRAUGHT Each year the label depicts an endangered species of bird Vodka & Housemade Ginger Beer Cabernet, Merlot, and Syrah blend together to create aromas of ripe Sparkling Campari Negroni Poured From a Nitro Faucet berries and sweet spice HOUSE SPECIALS Tony Truchard got his start in the wine biz when his Army post was Hand crafted cocktails created by the Quality Italian Denver Bartenders moved to Napa after his wife was injured when she slipped on a grape A.D. -

Capricci Wine List 120117 Definitiva

CAPRICCI WINE LIST AT CAPRICCI YOU CAN CHOOSE FROM A LARGE SELECTION OF WINE TO SUIT YOUR TASTE, BELOW IS OUR WINE LIST FOCUSING ON THE MOST POPULAR WINES FROM THE SHELF AS WELL AS A SOME HAND SELECTED MORE PRESTIGIOUS WINES. IN THE LIST WE HAVE INCLUDED SOME PERSONAL RECOMMENDATIONS OF WINES TO DRINK BY THE BOTTLE HERE AT CAPRICCI. PLEASE DON'T HESITATE TO ASK OUR STAFF FOR ANY ADVICE OR INFORMATION ON THE WINES OR FOR SPECIAL TAKE AWAY PRICES. OUR NATURAL WINES Wines produced from Natural viticulture, as genuine expression of different Regions of the Italian territories, with a limited use of synthetic pesticides, insecticides, copper and sulfur. They are produced by spontaneous fermentation, without corrections or clarifications and bottled unfiltered and with the least possible amount or zero sulfites. ** The BUBBLES ** Prosecco Sottoriva Col Fondo, Malibran (Veneto)............................................................................................£36,00 Col Fondo, (Sur-lie) literally means "on the yeasts". This Prosecco has no added sulfites and it’s characterized by a fine perlage and intense and complex notes of ripe fruit, bread crust and yeasts. Prosecco Colfondo 2014, Casa Belfi, Albino Armani (Veneto) …………………………………………..…...£33,00 The naturalness of this wine is confirmed by the analyses with a zero residue of chemical products. It has a yellow colour, and a fine and persistent perlage. It shows floral and fruity accents, accompanied by notes of citrus, yeast and bread crust. It has a full body, perfectly balanced by a good acidity. ** The WHITES ** Vermentino Marittimo, 2015 Antonio Camillo (Tuscany)…………………………………………………......£29,00 Freshness is the main feature of this Tuscan wine, thanks to an acidity, which is unusual for a wine from this Region, the Maremma, on the lower part of the province of Grosseto. -

JR-Diffusion-Portfol

BRAND PORTFOLIO When you’re seeking earth’s natural chemistry, microbiology & true love for the fruit in one single wine, your best bet is to turn to small producers. These wine makers have the luxury to craft quality because they don’t cater to mass-market demands. And when you want to reach them, only independent wine merchants will roll up their sleeves to find them for you. When you live in a world overwhelmed by technology, there’s a constant search for simplicity & urge to go back to old, traditional ways. JR Diffusion is exactly that! Based in South of France, we handpick rising Artisan vine growers from surprising “terroirs”. We’re bringing you back the lost origins of French wines & the true meaning of what “terroir” stands for! From sustainable practices to humble farmers that follow early monks’ practices, we work with vine growers that dedicated their life to create wine masterpieces. Dreamers, agronomists, vintners... I spent times in vineyards across France and overseas to unearth “artists vignerons”. The raw experience that comes with soil under your nails is the most authentic knowledge. I have learned their way of growing vines, making wines and drinking `brut de cuve`. This portfolio is promoting years and years of vine growing tradition with the same philosophy; growing organic, biodynamic or natural berries. Why JR Diffusion? It’s wine simplicity. It’s an attitude. It’s harkening back to lost ways of living. It’s a philosophy. Yours & Ours. Sylvain Boutee Marcel Gisclard Vincent Rapin Lionel Faury Clos des Boutes Domaine -

Agreement Between the European Community and the United States of America on Trade in Wine

L 87/2 EN Official Journal of the European Union 24.3.2006 AGREEMENT between the European Community and the United States of America on trade in wine The EUROPEAN COMMUNITY, hereafter ‘the Community’, and The UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, hereafter ‘the United States’, hereafter referred to jointly as ‘the Parties’, RECOGNISING that the Parties desire to establish closer links in the wine sector, DETERMINED to foster the development of trade in wine within the framework of increased mutual understanding, RESOLVED to provide a harmonious environment for addressing wine trade issues between the Parties, HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS: TITLE I INITIAL PROVISIONS Article 1 Objectives The objectives of this Agreement are: (a) to facilitate trade in wine between the Parties and to improve cooperation in the development and enhance the transparency of regulations affecting such trade; (b) to lay the foundation, as the first phase, for broad agreement on trade in wine between the Parties; and (c) to provide a framework for continued negotiations in the wine sector. Article 2 Definitions For the purposes of this Agreement: (a) ‘wine-making practice’ means a process, treatment, technique or material used to produce wine; (b) ‘COLA’ means a Certificate of Label Approval or a Certificate of Exemption from Label Approval that results from an approved Application for and Certification/Exemption of Label/Bottle Approval, as required under US federal laws and regulations and issued by the US Government that includes a set of all labels approved to be firmly affixed to a bottle of wine; 24.3.2006 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 87/3 (c) ‘originating’ when used in conjunction with the name of one of the Parties in respect of wine imported into the territory of the other Party means the wine has been produced in accordance with either Party’s laws, regulations and requirements from grapes wholly obtained in the territory of the Party concerned; (d) ‘WTO Agreement’ means the Marrakesh Agreement establishing the World Trade Organisation, done on 15 April 1994. -

Natural, Organic & Biodynamic Wine

Natural, Organic & Biodynamic Wine “NATURAL” Wine: • General, broad reference to wines made in low-tech, non-interventionist style, e.g…. o Low or no use of chemicals in vineyard o Native yeasts used in fermentation o Low or no use of sulfur in winery o No chemical or technical “adjustments” to the final wine • Technically, zero regulations about what can/can’t be declared “natural” “ORGANIC” Wine: • Organic defined by USDA National Organic Program (NOP) as a product that uses no pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, sewage sludge, genetically modified organisms, or ionizing radiation • To be labeled as organic in US, must be inspected and approved by USDA • TTB, USDA and NOP labeling laws for wines sold in the US: o Organic: at least 95% organically produced ingredients and NO added sulfur allowed (or less than 10 ppm) o 100% Organic: 100% organically produced ingredients and NO added sulfur allowed (or less than 10 ppm) § Additional approved labeling: USDA Organic seal; “Certified Organic by ____” o Made from organic grapes: MUST note “contains sulfites” § Is it a problem if “made from organic grapes” can also include up to 30% non- organic grapes or “other ingredients”? § Is it a problem if many wines are made entirely organically yet with sulfur and so can’t be labeled organic when sold in US? § In the EU, wines with up to 100 ppm of sulfites can be labeled organic “BIODYNAMIC” Wine: • Biodynamic agriculture is a sustainable system proposed by Rudolf Steiner that involves using natural preparations in the field and following the lunar calendar for viticulture/vinification steps o Natural preparations are all organic, herb-, root- or animal-based products o Lunar calendar suggests fruit/flower/root/leaf days corresponding to certain tasks such as picking, pruning, racking, bottling • Many producers practice biodynamics but are not certified (expensive process) • Major certifying body is Demeter; certified wines can carry seal on their label All class outlines are copyright of Corkbuzz Wine Studio. -

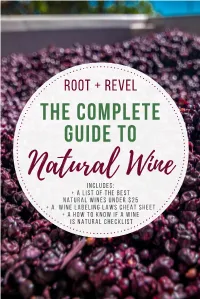

THE COMPLETE GUIDE to Natural Wine

ROOT + REVEL THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO Natural Wine INCLUDES: + A LIST OF The Best Natural Wines Under $25 + a Wine Labeling Laws CHEAT SHEET + a How To Know if a Wine Is Natural Checklist The Best Natural Wine Brands Under $25 Sokol Blosser 2014 Willamette Valley Pinot Gris, $19 Certified Organic, LEED Certified and Certified B Corp Brooks Wines, select Riesling + Pinot Noir, $20-$24 Certified Biodynamic Preston Farm & Winery 2015 Sauvignon Blanc, $22 Certified Biodynamic Honoro Vera Organic Monastrell, $8 Certified Biodynamic and Organic by both the EU and U.S. Art. Terra Organic, $15 Certified Organic Monte Bernardi 2014 Retromarcia Chianti Classico, $20 Certified Organic Badger Mountain NSA Riesling, Chardonnay, Merlot, and Cabernet Sauvignon, $12-$16 Certified Organic Domaine des Bacchantes 2014 Côtes du Rhône Rouge, $14 Part of a natural wine co-op that uses no external yeasts, no filtering, no fining and no enzymes. Annona Multepulciano d’Abruzzo ‘Modo Antico, $24 Made with native yeast, and without fining, filtration, or added sulfites Barmés Buecher 2014 Riesling Tradition, $20 Certified Biodynamic Pacific Rim Organic Riesling, $15 Certified Biodynamic and Organic © 2016 Root + Revel The Best Natural Wine Brands Under $25 Golan Heights Winery 2014 Yarden Chardonnay Odem, $22 Certified Organic; Native yeast is the only additive. Mahi Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc, $20 Certified Organic; Indigenous Yeast, Vegan Trader Joe's Noble Fin Pinot Noir, $4.99 Made with organic grapes; additives unknown Grgich Hills Estate Fume Blanc, $31 Certified -

Cantine Europa | Sibiliana Roceno Nero D'avola Sicilia

Sibiliana Roceno Nero d’Avola Sicilia DOC Historically, Nero d'Avola had a reputation in Italy for being hard to drink - with its Winemaker: Giacomo Spanò wild bramble and rustic tannins, it was often what they described as "spigaloso" or Generation: 3rd "edgy". In the past decade especially, that reputation has rapidly been changing thanks to wines like this one. Low in yield and high in quality, this unoaked Nero d'Avola from western Sicily showcases loads of Amarena cherry, tobacco, and round, balanced tannins, making it easy to advance to the next glass! Perfect with zesty pasta, roasted meats, and Napolitana-style pizza. WINEMAKER BIOGRAPHY Founded by a group of local farmers in 1962 in what is today the town of Petrosino, Cantine Europa is now one of the largest cooperatives of small growers in western Sicily. That established, all members are committed to sustainable farming (including picking by hand and dry-farming) and nearly all of the Cantine's offerings are DOC. ENOLOGIST Giacomo Spanò TASTING NOTES Color Ruby Nose Blackberry, blueberry, cherry, tobacco and vanilla Palate Amarena cherry and wild berries with a hint of black olive Finish Clean, medium VINEYARD & VINIFICATION Vineyard Location Sicilia DOC, Sicily Varietals List 100% Nero d'Avola Farming Practices Non-certified organic, with no chemicals used; dry-farmed; vegan; picked by hand Elevation 50-200 m Soils Argilla (clay) Maturation Summary Bottled for 3 months Alcohol 13.0 % Acidity 3.45 g/liter Residual Sugar 5 g/liter Annual Production 180,000 bottles REGION SICILY A Mediterranean crossroads and Italy’s largest autonomia, Sicily has been home to winemaking for some 6000 years. -

May 2017 Wine Club Write Up.Pages

HIGHLAND FINE WINE MAY 2017 HALF CASE - RED Tami’ Nero d’Avola Terre Siciliane - Sicily, Italy (Mixed/Red Club) $19.99 From young winemaker Arianna Occhipinti, one of Sicily’s rising stars, this rich, supple wine is a crowd favorite. Formerly a blending grape, Nero d’Avola has seen a well deserved renaissance over the last 20 years. Farmed almost exclusively in Sicily, Nero loves the heat and sunshine found in in the southwestern commune of Vittoria. Due to the highly active volcano Mount Etna, the soil in Sicily is considered the youngest in the world, producing a dark, mineral driven, dry red wine. Terra d’ Alter Alentejano Rosso - Alentejo, Portugal (Mixed/Red Club) $14.99 Alentjo is lacated south and east of Lisbon and is much better known for there historical production of wine corks from the indigenous cork trees in the region. The region has historically produced wines for local consumption but in the past decade much more wine has been imported from the region. This blend consists of grapes that are known, Aragonez (local name for Tempranillo) and Syrah, and grapes that are unkown and local like Trincadeira. The wine is pleasantly earthy with a dense red fruit flavor and and clean, dried herb feel on the finish. This is classic BBQ wine and will go with grilled meats and fish. Ronan by Clinet Bordeaux Rouge - Bordeaux, France (Mixed/Red Club) $13.99 Chateau Clinet is located in Pomerol and is well known for there velvety Merlot and Cabernet Franc blend. They have also recently begun a negociant business for larger production and have long standing contracts with growers that produce drinkable and outstanding Merlot wines for the price. -

Baldanza at the Post

Baldanza *ORGANIC Organic wines are produced using methods that do not involve modern synthetic inputs such as synthetic pesticides and chemical fertilizers, do not contain genetically modified organisms, and are processed using a minimum amount of authorized additives. Low amounts of added sulfites are generally acceptable. Due to the various food standards agencies throughout the world, there are many different guidelines and regulations that determine whether a wine can bear an organic seal in a particular country. **BIODYNAMIC Biodynamic viticulture is a method of organic farming that originated out of the work of Rudolf Steiner in 1920’s Europe. It considers the vines and the winery as a part of the larger environment, balancing the soil, plants, and animals in a self- nourishing, living system. Methods unique to biodynamic farming (not found in organic viticulture) include the use of an astronomical sowing and planting calendar. Very few additives are used in the grape-growing and winemaking. There are independent certification agencies for biodynamic products, most of which are members of Demeter International. N ATURAL There is no official definition or classification system for natural wines. Simply put, natural wine is just fermented grape juice. No added ingredients whatsoever. While you may not be able to taste the difference between an organic/biodynamic wine and its mass-produced equivalent, you must certainly will find natural wines to be unique in both nose and palate. COCKTAILS - 15 TANG-GARINE flor de cana rum, tangerine, -

Martorana | Organic Nero D'avola Sicilia

Organic Nero d’Avola Sicilia DOC Grown at altitude on a hill directly facing the Mediterranean, this deep, juicy, and vibrant wine takes Sicily’s main varietal to new heights! Although it’s unoaked, low yields and a longer maceration time lead to intense concentration and well- Winemaker: Giuseppe Martorana rounded tannins, allowing the considerable fruit to shine. Layers of cherry cordial, Generation: 2nd boysenberry jam (minus the sweetness), blueberry skin and blackberry seed all grace the palate. With this wine, Giuseppe’s 35 year-old vines have truly hit their stride! WINEMAKER BIOGRAPHY After a storied career in law enforcement, winemaker Giuseppe Martorana now produces small-batch Nero d'Avola with his youngest daughter, Giadda. They live and work on the sun-drenched coast of Agrigento - also home to countless Greek ruins - along Sicily's SW shore. ENOLOGIST Giuseppe Martorana TASTING NOTES Color Brilliant ruby-violet Nose Boysenberry, ripe round cherry, and slate Palate Cherry cordial and wild berry jam (without being sweet) Finish Juicy and vibrant VINEYARD & VINIFICATION Vineyard Location Sicilia DOC, Sicily Vineyard Size 20 ha Varietals List 100% Nero d’avola Farming Practices Organically farmed (EU certified), including dry-farmed; grapes picked by hand Elevation 250 m Soils Calcareous chalk-sandstone mix Maturation Summary Bottled for 3 months Alcohol 14.0 % Acidity 6.5 g/liter Residual Sugar 1.8 g/liter REGION SICILY A Mediterranean crossroads and Italy’s largest autonomia, Sicily has been home to winemaking for some 6000 years. In the 8th century BC, the Greeks brought more advanced viticultural techniques to the island, and a brisk trade with Phoenicians and Romans ultimately followed.