Coastal Security Paradox Abhijit Singh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Online" Application the Candidates Need to Logon to the Website and Click Opportunity Button and Proceed As Given Below

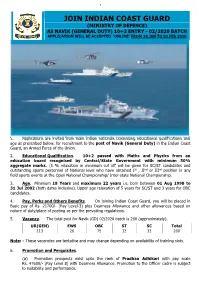

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2020 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 26 JAN TO 02 FEB 2020 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with Maths and Physics from an education board recognised by Central/State Government with minimum 50% aggregate marks. (5 % relaxation in minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports personnel of National level who have obtained Ist , IInd or IIIrd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Inter-state National Championship. 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. born between 01 Aug 1998 to 31 Jul 2002 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits. On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay of Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the prevailing regulations. 5. Vacancy. The total post for Navik (GD) 02/2020 batch is 260 (approximately). UR(GEN) EWS OBC ST SC Total 113 26 75 13 33 260 Note: - These vacancies are tentative and may change depending on availability of training slots. 6. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist upto the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. -

Join Indian Coast Guard (Ministry of Defence) As Navik (General Duty) 10+2 Entry - 02/2018 Batch Application Will Be Accepted ‘Online’ from 24 Dec 17 to 02 Jan 18

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2018 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 24 DEC 17 TO 02 JAN 18 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age, as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with 50% marks aggregate in total and minimum 50% aggregate in Maths and Physics from an education board recognized by Central/State Government. (5 % relaxation in above minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports person of National level who have obtained 1st, 2nd or 3rd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Interstate National Championship. This relaxation will also be applicable to the wards of Coast Guard uniform personnel deceased while in service). 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. between 01 Aug 1996 to 31 Jul 2000 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits:- On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the regulation enforced time to time. 5. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist up to the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. 47600/- (Pay Level 8) with Dearness Allowance. -

Smart Border Management: Indian Coastal and Maritime Security

Contents Foreword p2/ Preface p3/ Overview p4/ Current initiatives p12/ Challenges and way forward p25/ International examples p28/Sources p32/ Glossary p36/ FICCI Security Department p38 Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security September 2017 www.pwc.in Dr Sanjaya Baru Secretary General Foreword 1 FICCI India’s long coastline presents a variety of security challenges including illegal landing of arms and explosives at isolated spots on the coast, infiltration/ex-filtration of anti-national elements, use of the sea and off shore islands for criminal activities, and smuggling of consumer and intermediate goods through sea routes. Absence of physical barriers on the coast and presence of vital industrial and defence installations near the coast also enhance the vulnerability of the coasts to illegal cross-border activities. In addition, the Indian Ocean Region is of strategic importance to India’s security. A substantial part of India’s external trade and energy supplies pass through this region. The security of India’s island territories, in particular, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, remains an important priority. Drug trafficking, sea-piracy and other clandestine activities such as gun running are emerging as new challenges to security management in the Indian Ocean region. FICCI believes that industry has the technological capability to implement border management solutions. The government could consider exploring integrated solutions provided by industry for strengthening coastal security of the country. The FICCI-PwC report on ‘Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security’ highlights the initiatives being taken by the Central and state governments to strengthen coastal security measures in the country. -

Indian Coast Guard

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY), NAVIK(DOMESTIC BRANCH) AND YANTRIK 02/2021 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 05 JAN 2021 (1000 hrs) TO 19 Jan 2021 (1800 hrs) 1. Eligibility Conditions. Online applications are invited from MALE INDIAN CITIZENS possessing educational qualifications and age as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty), Navik (Domestic Branch) and Yantrik in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. (a) Navik (General Duty). 10+2 passed with Maths and Physics from an education board recognized by Council of Boards for School Education (COBSE). (b) Navik (Domestic Branch). 10th Class passed from an education board recognized by Council of Boards for School Education (COBSE). (c) Yantrik. 10th class passed from an education board recognized by Council of Boards for School Education (COBSE) and Diploma in Electrical/ Mechanical / Electronics and Telecommunication (Radio/Power) Engineering approved by All India Council of Technical Education (AICTE). Note: - Education Boards listed in COBSE website as on date of registration shall only be considered. 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years as follows: - (a) For Navik (GD) and Yantrik. Born between 01 Aug 1999 to 31 Jul 2003 (both dates inclusive). (b) For Navik (DB). Born between 01 Oct 1999 to 30 Sep 2003 (both dates inclusive). Note: -upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC (non-creamy) candidates is applicable only if posts are reserved for them. 2 4. Vacancy. The number of post for category wise recruitment are as follows: - Post UR(GEN) EWS OBC ST SC Total Navik(General Duty) 114 33 83 7 23 260 Navik (Domestic Branch) 22 6 8 3 11 50 Yantrik (Mechanical) 13 3 7 4 4 31 Yantrik (Electrical) 4 1 1 0 1 7 Yantrik (Electronics) 7 0 2 0 1 10 Note: (a) These vacancies are tentative and may change depending on availability of training slots. -

SP's NF 03-09 Resize.Indd

Principle Sponsor of C4I2 Summit in Taj Palace, New Delhi, 10-11 August ProcurementMinistry Process of Home elaborated Affairs Elements • Eventsʼ • Reference IDS Headquartersʼ - Special Insertrole in • Indiaʼs Homeland Security & IN THIS EDITION - ������������� AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION � ������������ 451964-2009 SP GUIDE PUBLICATIONS Initiatives announced by � WIDENING ����� US Secretary of State � ������ HORIZONS... Hillary Clinton to curb � ������� Somali-based maritime piracy. � ����������� 4 Page 14 2008 ������������������� ������������������� 2009 � ������ 2008 ������������������������������������������������������������������� 2009 The Indian Coast ����������������������������������������� Guard is a lean yet efficient and ��������������� visible force ����������������������� ������������������������ ����������������������������������������������� ��������������� who protect the SP's MYB 0809 CVR01.indd 1 4/20/09 3:20:57 PM nation’s interest in the maritime � � � � � � � ������� zones. Issue 3 200 9 ▸ V o l 4 N o 3 “Equipment and training alone will not boost 3Page 11 morale of the armed forces. The welfare of Rs 75.00 (INDIA-BASED BUYER ONLY) WWW.SPSNAVALFORCES.NET the armed forces deployed in far-flung remote areas, in deep sea submarines and dense for- est have to be protected. I will take personal interest to improve their service conditions.” —A.K. Antony on taking over as Defence Minister The last cou- ple of months have been very eventful in the South Asian region. Foremost was the elections in India wherein � �Indians � � � � � �spoke � in one voice SP’s Exclusive and voted for stability. The UPA has returned to power minus the handicap of the Left. A.K. Antony is back as Defence Minister, which should spell conti- nuity and speedier pace of modernisation. P.C. Chidambaram also made a comeback as Home Minister to fulfill his promise to implement certain security measures within 100 days. -

*Indigeneously Built Indian Coast Guard Ship 'Vigraha' Dedicated to the Nation* Defence Minister Shri Rajnath Singh Dedicat

*Indigeneously built Indian Coast Guard Ship 'Vigraha' dedicated to the Nation* Defence Minister Shri Rajnath Singh dedicated to the nation, the indigenously built Coast Guard Ship ‘Vigraha’ in Chennai today. Calling it one of the important steps towards “Atma Nirbhar Bharat”, he said the newly commissioned vessel is indigenous from its design conception to development. Raksha Mantri also highlighted that for the first time in the history of Indian defence, contracts for not one or two, but seven vessels have been signed with a private sector company. And more importantly, within seven years of signing this agreement in 2015, not only launch but also the commissioning of all these seven vessels has been completed today. Raksha Mantri recalled the Coast Guard’s role in extending help to neighbouring countries in line with the spirit of inclusiveness. He hailed the role of Coast Guard in providing pro-active help in saving Very large crude carrier MT 'New Diamond' last year, and the cargo ship MV 'X-Press Pearl'. Raksha Mantri also commended the efforts of Coast Guard for its assistance provided to Mauritius during the oil spill from the 'Wakashio' motor vessel. On the occasion he also lauded the efforts of Coast Guard towards realising the vision of SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region) envisaged by the Hon'ble Prime Minister with focus on spirit of friendship, openness, dialogue and co-existence with the neighbours with keen sense of duty as its core. The Ship will be based at Visakhapatnam and operate on India's Eastern Seaboard under the Operational and Administrative Control of the Commander, Coast Guard Region (East). -

Weekly Career Bulletin

Weekly Career Bulletin (Information related to Employment & Career) Published by the Model Career Centre, Agartala, Directorate of Employment Services & Manpower Planning, Govt. of Tripura VOL: II NO: 7 Agartala: 21st June- 26th June 2021 Date of Publication: 29-06-2021 TRIPURA RECRUITMENT For detailed information please visit NOTIFICATION https://joinindiancoastguard.cdac.in/assets/img/d ownloads/advertisenment.pdf TPSC has published notification regarding Mains Examination for recruitment to the post of Tripura Office of the Director General Assam Rifles, Forest Service Gr.-II under GA(P&T) Shillong – 793010, invites applications from Department.Govt. of Tripura . Provisional eligible sportspersons for recruitment of 131 vacant admission certificate will be available in TPSC posts of Rifleman / Riflewoman General Duty) online application portal www.tpscoline.in from 16th under Sports Quota Recruitment in Assam Rifles August, 2021. for the year 2021, Ministry of Home Affairs, For detailed information please visit Government of India. The Sport Disciplines are www.tpsc.tripura.gov.in Archery, Karate, Taekwondo, Judo, Equestrian, Fencing, Wushu, Football, Boxing, Sepak Takraw, Polo, Atheletics (40m, 3000M, 5000M) and Shooting (Pistol, Rifle). The last date for submission ALL INDIA RECRUITMENT of applications is 26th July 2021. NOTIFICATION For detailed information please visit Indian Coast Guard has published notification for https://www.assamrifles.gov.in/DOCS/RECRUIT the recruitment of 50 (Fifty) vacant posts of MENT/ADVERTIS.pdf Assistant Commandant General Duty, Tech (Engg / Elect) for 01-2022 Batch. Those Mazagon Dock Shipbuilders Ltd, Mumbai, has Candidates who are interested in the vacancy details given an employment notification for the & completed all eligibility criteria can read the recruitment of 1388 Non-Executive vacancies on Notification & Apply Online. -

The Coast Guard (Seniority and Promotion) Rules, 1987 CONTENTS

The Coast Guard (Seniority and Promotion) Rules, 1987 CONTENTS PART- I PRELIMINARY 1. Short title and commencement 2. Definitions PART – II SENIORITY AND PROMOTION RULES - OFFICERS 3. Basic date 4. Seniority of officers 5. Seniority of permanently absorbed officers, re-employed officers and directly recruited officers 6. Authority for promotion 7. Promotion rules 8. Officiating promotion 9. Local ranks 10. Qualifications for promotion 11. Refund of cost of training 12. Probation 13. Refusing promotion 14. Medical 15. Officers of lower medical categories 16. Erroneous promotion PART – III PROMOTION RULES - ENROLLED PERSONS 17. Basic Date 18. Seniority 19. Promotion rules 20. Qualifications for promotion 21. Authority for promotion 22. Leadership course 23. Probation 24. Reservation for unsuitability 25. Reversion 26. Limits of reversion 27. Authority for reversion 28. Procedure 29. Promotion after reversion 30. Promotion by Director-General 31. Inability of Enrolled Personnel to undergo Departmental examination due to exigency of service 32. Failure in basic courses 33. Number of chances in Departmental examination 34. Promotion after reduction in rank 35. Refusal to undergo Departmental examination 36. Refusing promotion 37. Medical 38. Erroneous promotion 39. Reference to rank and service 40. Removal of doubts ANNEXURE - 1 Qualifications for Promotion - Officers General Duty Branch (Law) ANNEXURE - 2 Qualifications for Promotion - Officers General Duty Branch ANNEXURE - 3 Qualifications for Promotion - Officers Technical (Engineering/Electrical) -

2021-08-28 L&T-Built Seventh OPV, ICGS Vigraha Commissioned Into the Indian Coast Guard

L&T-Built Seventh OPV, ICGS Vigraha Commissioned into the Indian Coast Guard Unprecedented Feat of Delivering of All 7 Ships Ahead of Schedule Chennai, August 28, 2021: L&T-built Offshore Patrol Vessel ICGS Vigraha was commissioned into the Indian Coast Guard (ICG) by Shri Rajnath Singh, Hon’ble Defence Minister of India at Chennai today, showcasing its commitment to ‘Aatmanirbhar Bharat’ by completing delivery of all seven OPVS ahead of contractual schedule. Shri M K Stalin, Hon’ble Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, General MM Naravane, PVSM, AVSM, SM, VSM, ADC, Chief of the Army Staff, Director General K Natarajan, PVSM, PTM, TM, Director General Indian Coast Guard, Mr JD Patil, Whole Time Director (Defence & Smart Technologies) and Member of the L&T Board and other dignitaries were present at the event. ICGS Vigraha is the last vessel in the series of seven Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs) built by L&T under a MoD contract signed in 2015. Seven OPVs programme bestowed many laurels to the Indian Shipbuilding Industry, including: • Delivery of all 7 OPVs ahead of contractual delivery schedule, including ‘First of Class’ OPV ‘ICGS Vikram’ • For the first time, entire design and construction of the OPV class of ships by an Indian private sector shipyard • Achieving the build period of mere 19.5 months, clearing all Sea Acceptance Trials in a single sea sortie for 5th OPV ‘ICGS Varad’ • Extensive use of Shipbuilding 4.0 tools with in-house developed IT systems for real time data capturing, analysis & decision making for effective project monitoring and control This was achieved during the tough conditions of COVID-19 pandemic by following COVID- appropriate behaviour among all workmen at our shipyards. -

1. the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union, Offers A

1. The Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union, offers a challenging career to young and dynamic Indian male/female candidates for various branches as an Assistant Commandant (Group ‘A’ Gazetted Officer) and invites ‘online’ application. 2. Branch and Eligibility. Indian citizens having following minimum qualifications are eligible to apply: SL ENTRY AGE GENDER EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION (a) GENERAL Born between 01 Jul Male (i) Candidates who have passed Bachelor’s DUTY 1995 to 30 Jun 1999 degree from any recognised university with st (Both dates minimum 60% marks in aggregate (i.e. 1 Semester to 8th Semester for BE/B.Tech inclusive). st (b) GENERAL Born between 01 Jul Female Course or 1 year to last year for Bachelor Degree candidates wherever applicable). DUTY (SSA) 1995 to 30 Jun 1999 (Both dates (ii) Mathematics and Physics as subjects up to inclusive). intermediate or class XIIth of 10+2+3 scheme of education or equivalent with 60% aggregate in Mathematics and Physics. (Candidates not in possession of Physics and Maths in 10+2(intermediate) or equivalent level are not eligible for General Duty (GD) and General Duty (SSA) (c) Commercial Born between 01 Jul Male/ Candidates holding current /valid Pilot Entry 1995 to 30 Jun 2001 Female Commercial Pilot Licence (CPL) issued/ (CPL) (SSA) (Both dates inclusive). validated by Director General of Civil Aviation (DGCA). Minimum educational qualification – XIIth pass (Physics and Mathematics)with 60% marks in aggregate. SL ENTRY AGE GENDER EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION (d) Technical Born between 01 Jul Male (i) Engineering degree with 60% marks in (Engineering 1995 to 30 Jun 1999 aggregate or Should have passed Sections A & Electrical) (Both dates inclusive). -

Military Studies: Para Military Forces: the Assam Rifles and Central Industrial Security Force- Flexiprep

9/22/2021 Military Studies: Para Military Forces: The Assam Rifles and Central Industrial Security Force- FlexiPrep FlexiPrep Military Studies: Para Military Forces: The Assam Rifles and Central Industrial Security Force (For CBSE, ICSE, IAS, NET, NRA 2022) Get unlimited access to the best preparation resource for CBSE/Class-6 : get questions, notes, tests, video lectures and more- for all subjects of CBSE/Class-6. Para Military Forces ©FlexiPrep. Report ©violations @https://tips.fbi.gov/ A paramilitary force is a semi-militarized force whose organizational structure, tactics, training, subculture, functions are similar to those of a professional military, but which is not included as part of a state՚s formal armed forces. Indian Paramilitary Forces refer to three organisations that assist the Indian Armed Forces closely and are led by officers of the Indian Army or Indian Navy. Earlier, the term ‘paramilitary’ forces were used for eight forces: 1. Assam Rifles 2. Special Frontier Force 3. Indian Coast Guard 4. Central Reserve Police Force 5. Border Security Force 6. Indo-Tibetan Border Police 7. Central Industrial Security Force 8. Sashastra Seema Bal. from 2011, they have been regrouped into two classes whereby the later five are called Central Armed Police Forces (CAPF) . The first three are the current paramilitary forces of India - Assam Rifles (part of Home Ministry) , Special Frontier Force (part of Cabinet Secretariat) and Indian Coast Guard (part of Ministry of Defense) . The Assam Rifles It is the oldest paramilitary force of India. the Assam Rifles and its predecessor units have served in a number of roles, conflicts and theatres including World War I where they served in Europe and the Middle East, and World War II where they served mainly in Burma. -

COMMISSIONING of ICGS ANNIE BESANT and AMRIT KAUR Indian

COMMISSIONING OF ICGS ANNIE BESANT AND AMRIT KAUR Indian Coast Guard Ship Annie Besant and Amrit Kaur, second and third in the series of five Fast Patrol Vessels were commissioned at Kolkata on 12 Jan 20 by Dr Ajay Kumar, Defence Secretary, Govt of India in the presence of Director General Krishnaswamy Natarajan, PTM, TM, Director General Indian Coast Guard, Rear Admiral VK Saxena, IN(Retd), CMD, M/s GRSE and other senior dignitaries of the Central and State Government. Indian Coast Guard Ship Annie Besant has been named in honour of Ms Annie Besant, an esteemed socialist and her eminent achievements towards the nation. Ms Annie Besant was a theosophist, women’s rights activist, writer, orator and supporter of Indian freedom. She was also a philanthropist and a prolific author who had written over three hundred books & pamphlets and contributed in foundation of Banaras Hindu University. In 1916, she established the Indian Home Rule League, of which she became President. The ship is being based at Chennai under the operational and administrative control of Commander, Coast Guard Region East. Indian Coast Guard Ship Amrit Kaur derives her name from Ms Raj Kumari Amrit Kaur who belonged to the ruling family of Kapurthala, Punjab. She took an active part in Salt Satyagraha and Quit India Movement. She served the Independent India as its first Health Minister. She worked towards upliftment of Harijan and progress of women. She was the founder member of All India Womens’ Conference and founder President of Indian Council for Child Welfare. The ship is being based at Haldia under the operational and administrative control of Commander, Coast Guard Region North East.