Captain Suvarat Magon, in Maritime Security Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admiral Sunil Lanba, Pvsm Avsm (Retd)

ADMIRAL SUNIL LANBA, PVSM AVSM (RETD) Admiral Sunil Lanba PVSM, AVSM (Retd) Former Chief of the Naval Staff, Indian Navy Chairman, NMF An alumnus of the National Defence Academy, Khadakwasla, the Defence Services Staff College, Wellington, the College of Defence Management, Secunderabad, and, the Royal College of Defence Studies, London, Admiral Sunil Lanba assumed command of the Indian Navy, as the 23rd Chief of the Naval Staff, on 31 May 16. He was appointed Chairman, Chiefs of Staff Committee on 31 December 2016. Admiral Lanba is a specialist in Navigation and Aircraft Direction and has served as the navigation and operations officer aboard several ships in both the Eastern and Western Fleets of the Indian Navy. He has nearly four decades of naval experience, which includes tenures at sea and ashore, the latter in various headquarters, operational and training establishments, as also tri-Service institutions. His sea tenures include the command of INS Kakinada, a specialised Mine Countermeasures Vessel, INS Himgiri, an indigenous Leander Class Frigate, INS Ranvijay, a Kashin Class Destroyer, and, INS Mumbai, an indigenous Delhi Class Destroyer. He has also been the Executive Officer of the aircraft carrier, INS Viraat and the Fleet Operations Officer of the Western Fleet. With multiple tenures on the training staff of India’s premier training establishments, Admiral Lanba has been deeply engaged with professional training, the shaping of India’s future leadership, and, the skilling of the officers of the Indian Armed Forces. On elevation to Flag rank, Admiral Lanba tenanted several significant assignments in the Navy. As the Chief of Staff of the Southern Naval Command, he was responsible for the transformation of the training methodology for the future Indian Navy. -

"Online" Application the Candidates Need to Logon to the Website and Click Opportunity Button and Proceed As Given Below

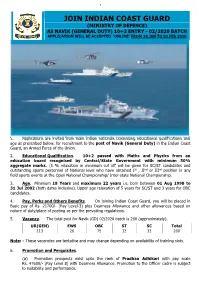

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2020 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 26 JAN TO 02 FEB 2020 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with Maths and Physics from an education board recognised by Central/State Government with minimum 50% aggregate marks. (5 % relaxation in minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports personnel of National level who have obtained Ist , IInd or IIIrd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Inter-state National Championship. 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. born between 01 Aug 1998 to 31 Jul 2002 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits. On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay of Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the prevailing regulations. 5. Vacancy. The total post for Navik (GD) 02/2020 batch is 260 (approximately). UR(GEN) EWS OBC ST SC Total 113 26 75 13 33 260 Note: - These vacancies are tentative and may change depending on availability of training slots. 6. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist upto the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. -

Securing India's Littorals “Keeping the Peace”, Ashish Pub, Delhi, 1989

Sanjay Badri-Maharaj Keedysville, MD, The Consortium Press, 2000. 15. K. Sandhu, “Arming Moves: Upgradation of Arms Likely” in India Today, March 31st, 1991, pp. 42. S. Ghosh Securing India's Littorals “Keeping the Peace”, Ashish Pub, Delhi, 1989. pp. 133-134. S. Gupta & G Thukral, “Punjab Police: Ribeiro's Challenge” in India Today, April 30, 1986, pp. 32. & 34. The .303 rifle is still widely used. 16. It would appear that storage in most Indian police stations consists of leaning the weapon against a wall if it is a V. Sakhuja* rifle or hanging it from a nail or hook from the wall if it is a pistol. 17. Somit Sen & Aneesh Pandis, “Police Strengthened against Underworld”, Times of India, October 8, 2001. 18. http://specials.rediff.com/news/2008/dec/10slid2-ultimately-it-was-the-havaldar-who-caught-the- terrorist.htm Threats to Littoral 19. It would appear that when being given special training by the army, policemen from armed police battalions in UP, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh were compelled to enhance their marksmanship skills to meet basic proficiency The term littoral has its origins in oceanographic literature and is described as standards. Unfortunately, the forces being trained, while destined to be quite competent, are tasked with anti- Naxal operations and not urban counter-terrorism. coastal or shore region. In geographic terms, it is understood as a space where sea meets the land. In 1954, Samuel Huntington argued that major battles on the high seas was a thing of the past and the 'new locale' of naval combat had shifted from the high seas to the coastal areas which are also referred to as 'rimland, the periphery, or the littoral.'1 Further, the littorals would be the new strategic space where 'decisive battles of the Cold War and of any future hot war will be fought'. -

Join Indian Coast Guard (Ministry of Defence) As Navik (General Duty) 10+2 Entry - 02/2018 Batch Application Will Be Accepted ‘Online’ from 24 Dec 17 to 02 Jan 18

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2018 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 24 DEC 17 TO 02 JAN 18 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age, as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with 50% marks aggregate in total and minimum 50% aggregate in Maths and Physics from an education board recognized by Central/State Government. (5 % relaxation in above minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports person of National level who have obtained 1st, 2nd or 3rd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Interstate National Championship. This relaxation will also be applicable to the wards of Coast Guard uniform personnel deceased while in service). 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. between 01 Aug 1996 to 31 Jul 2000 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits:- On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the regulation enforced time to time. 5. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist up to the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. 47600/- (Pay Level 8) with Dearness Allowance. -

Smart Border Management: Indian Coastal and Maritime Security

Contents Foreword p2/ Preface p3/ Overview p4/ Current initiatives p12/ Challenges and way forward p25/ International examples p28/Sources p32/ Glossary p36/ FICCI Security Department p38 Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security September 2017 www.pwc.in Dr Sanjaya Baru Secretary General Foreword 1 FICCI India’s long coastline presents a variety of security challenges including illegal landing of arms and explosives at isolated spots on the coast, infiltration/ex-filtration of anti-national elements, use of the sea and off shore islands for criminal activities, and smuggling of consumer and intermediate goods through sea routes. Absence of physical barriers on the coast and presence of vital industrial and defence installations near the coast also enhance the vulnerability of the coasts to illegal cross-border activities. In addition, the Indian Ocean Region is of strategic importance to India’s security. A substantial part of India’s external trade and energy supplies pass through this region. The security of India’s island territories, in particular, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, remains an important priority. Drug trafficking, sea-piracy and other clandestine activities such as gun running are emerging as new challenges to security management in the Indian Ocean region. FICCI believes that industry has the technological capability to implement border management solutions. The government could consider exploring integrated solutions provided by industry for strengthening coastal security of the country. The FICCI-PwC report on ‘Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security’ highlights the initiatives being taken by the Central and state governments to strengthen coastal security measures in the country. -

Unhcr Flash Update

UNHCR FLASH UPDATE LIBYA 21 - 27 April 2018 Highlights UNHCR is responding to the urgent humanitarian situation of around 800 Key figures: refugees and migrants who are detained in the Zwara detention centre (115 km west of Tripoli). On 25 April, UNHCR and its partner International 184,612 Libyans Medical Corps (IMC) visited the facility, provided medical assistance, and currently internally dispatched non-food items for 800 refugees and migrants in detention. UNHCR, 1 displaced (IDPs) MSF and DRC are conducting an anti-scabies campaign inside the detention 368,583 returned facility. Due to the fact that the coastal road between Zwara and Tripoli is too dangerous, in coordination with the authorities, UNHCR is exploring the IDPs (returns evacuation of all persons of concern (Eritreans, Somali and Sudanese) from registered in 2016 - Zwara to Tripoli by airplane, logistics and security permitting. March 2018)1 51,519 registered Population Movements refugees and asylum- As of 26 April 2018, 5,109 refugees and migrants were rescued/intercepted seekers in the State of by the Libyan Coast Guard (LCG). During the week, over 600 refugees and Libya2 migrants were disembarked in Tripoli (322 individuals), Zwara (111 individuals), Azzawya (82 individuals) and Al Khums (94 individuals). On the 22 April, a 9,361 persons arrived shipwreck took place near Sabratha (75 km west of Tripoli) causing the loss of in Italy by sea in 20183 at least 11 lives at sea. The remaining 82 survivors were disembarked in Azzawya. Humanitarian and medical assistance was provided by UNHCR and 451 monitoring visits its partner IMC at all disembarkation points where the most vulnerable cases to detention centres so were identified. -

Ins Vikrant) at Csl, Kochi – 12 Aug 13

ADDRESS BY CNS LAUNCH CEREMONY OF INDIGENOUS AIRCRAFT CARRIER I (INS VIKRANT) AT CSL, KOCHI – 12 AUG 13 1. Shri AK Antony, Hon’ble Raksha Mantri, Shri GK Vasan, Hon’ble Minister for Shipping, Hon’ble Members of Parliament, Hon’ble Members of Legislative Assembly & Council, Vice Admiral Shekhar Sinha, Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Western Naval Command, Vice Admiral Satish Soni, Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Southern Naval Command, Commodore K Subramaniam, Chairman & Managing Director, Cochin Shipyard Limited, Flag Officers, Board of Directors of CSL, the proud work force of CSL, distinguished guests, members of the media, ladies and gentlemen. 2. I would at the outset like to thank the Hon’ble Raksha Mantri and the Hon’ble Minister of Shipping for their presence at this momentous occasion, which is historic not only for the Navy, but for the entire nation. I would also like to compliment the Chairman & Managing Director of Cochin Shipyard and his team for making this occasion a reality. 3. The Navy has always been conscious that designing and building warships is a strategic core capability for any country. After the first indigenous warship INS Ajay was constructed in 1960, 2 the then Prime Minister Smt Indira Gandhi, launched our first indigenous frigate INS Nilgiri in 1968. Since then we have never looked back. 4. The next significant capability achieved was in-house designing. The ships of Godavari, Brahmaputra, Delhi and Shivalik, designed by naval design teams, exemplify this niche competence/ we also constructed two conventional submarines. The valuable exposure to the technical know-how of submarine construction has helped us embark on an indigenous 30 year submarine building programme. -

SP's NF 03-09 Resize.Indd

Principle Sponsor of C4I2 Summit in Taj Palace, New Delhi, 10-11 August ProcurementMinistry Process of Home elaborated Affairs Elements • Eventsʼ • Reference IDS Headquartersʼ - Special Insertrole in • Indiaʼs Homeland Security & IN THIS EDITION - ������������� AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION � ������������ 451964-2009 SP GUIDE PUBLICATIONS Initiatives announced by � WIDENING ����� US Secretary of State � ������ HORIZONS... Hillary Clinton to curb � ������� Somali-based maritime piracy. � ����������� 4 Page 14 2008 ������������������� ������������������� 2009 � ������ 2008 ������������������������������������������������������������������� 2009 The Indian Coast ����������������������������������������� Guard is a lean yet efficient and ��������������� visible force ����������������������� ������������������������ ����������������������������������������������� ��������������� who protect the SP's MYB 0809 CVR01.indd 1 4/20/09 3:20:57 PM nation’s interest in the maritime � � � � � � � ������� zones. Issue 3 200 9 ▸ V o l 4 N o 3 “Equipment and training alone will not boost 3Page 11 morale of the armed forces. The welfare of Rs 75.00 (INDIA-BASED BUYER ONLY) WWW.SPSNAVALFORCES.NET the armed forces deployed in far-flung remote areas, in deep sea submarines and dense for- est have to be protected. I will take personal interest to improve their service conditions.” —A.K. Antony on taking over as Defence Minister The last cou- ple of months have been very eventful in the South Asian region. Foremost was the elections in India wherein � �Indians � � � � � �spoke � in one voice SP’s Exclusive and voted for stability. The UPA has returned to power minus the handicap of the Left. A.K. Antony is back as Defence Minister, which should spell conti- nuity and speedier pace of modernisation. P.C. Chidambaram also made a comeback as Home Minister to fulfill his promise to implement certain security measures within 100 days. -

(Defence Wing) Govenjnt of India New Vice Chief Of

PRESS INFOREATION BUREAU (DEFENCE WING) GOVENJNT OF INDIA NEW VICE CHIEF OF NAVY FLAG OFFICER COJ'INANDING—IN_CHIEF, sOVTHERN NAVAL CONMAND AND DEPUTY CHIEF OF NAVY ANNOUNCED New Delhi Agrahayana 07, 19109 November 28, 1987 Vice Admiral GN Hiranandani presently Flag Officer Commanding—in—Chief, Southern Naval Command (FOC—in—C, SNC) has been appointed as Vice Chief of Naval Staff. He will take over from Vice Admiral JG Nadkarni, the CNS Designate, who will assume the ofice of Chief of the Naval Staff on November Oth in the rank of Admiral. Vice Admiral L. Ramdas presently Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff has been appointed FOC—in—C, SNC. Vice Admiral RP Sawhney, presently Controller Warship Production and Acquisition at Naval Headnuarters, has been appointed as Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff. Vice Admiral GM Hiranandani -was commissioned in 1952 and received his initial training in the United Kingdom and later graduated from the Staff College, Greenwich (U.K.). In 1 971 he served as the Fleet Operations Officer, Western Fleet. His notable - commands at sea include that of the first Kashin class destroyer, INS Rajput which he commissioned in 1980. On promotion to flag rank he was appointed Chief of Staff, Western Naval Command and later Deputy Chief of Naval Staff in the rank of Vice Admiral. He is a recipient of the Param Vishst Seva Medal, Ati Vishist Seva, Medal and Nao Sena Medal. .1,2 -2-- Vice Admiral L. Ramdas was commissioned in 1953 and received his initial trai lug in the U.K.. A communication Specialist, he has held a number of importanf commands a't sea, which inolde Command of the Eastern Fleet, the aircraft carrier INS Vikrant and a modern patrol vessel squadron. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Refugee Policies from 1933 Until Today: Challenges and Responsibilities

Refugee Policies from 1933 until Today: Challenges and Responsibilities ihra_4_fahnen.indd 1 12.02.2018 15:59:41 IHRA series, vol. 4 ihra_4_fahnen.indd 2 12.02.2018 15:59:41 International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (Ed.) Refugee Policies from 1933 until Today: Challenges and Responsibilities Edited by Steven T. Katz and Juliane Wetzel ihra_4_fahnen.indd 3 12.02.2018 15:59:42 With warm thanks to Toby Axelrod for her thorough and thoughtful proofreading of this publication, to the Ambassador Liviu-Petru Zăpirțan and sta of the Romanian Embassy to the Holy See—particularly Adina Lowin—without whom the conference would not have been possible, and to Katya Andrusz, Communications Coordinator at the Director’s Oce of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. ISBN: 978-3-86331-392-0 © 2018 Metropol Verlag + IHRA Ansbacher Straße 70 10777 Berlin www.metropol-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten Druck: buchdruckerei.de, Berlin ihra_4_fahnen.indd 4 12.02.2018 15:59:42 Content Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust ........................................... 9 About the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) .................................................... 11 Preface .................................................... 13 Steven T. Katz, Advisor to the IHRA (2010–2017) Foreword The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, the Holy See and the International Conference on Refugee Policies ... 23 omas Michael Baier/Veerle Vanden Daelen Opening Remarks ......................................... 31 Mihnea Constantinescu, IHRA Chair 2016 Opening Remarks ......................................... 35 Paul R. Gallagher Keynote Refugee Policies: Challenges and Responsibilities ........... 41 Silvano M. Tomasi FROM THE 1930s TO 1945 Wolf Kaiser Introduction ............................................... 49 Susanne Heim The Attitude of the US and Europe to the Jewish Refugees from Nazi Germany ....................................... -

Unhcr Position on the Designations of Libya As a Safe Third Country and As a Place of Safety for the Purpose of Disembarkation Following Rescue at Sea

UNHCR POSITION ON THE DESIGNATIONS OF LIBYA AS A SAFE THIRD COUNTRY AND AS A PLACE OF SAFETY FOR THE PURPOSE OF DISEMBARKATION FOLLOWING RESCUE AT SEA UNHCR POSITION ON THE DESIGNATIONS OF LIBYA AS A SAFE THIRD COUNTRY AND AS A PLACE OF SAFETY FOR THE PURPOSE OF DISEMBARKATION FOLLOWING RESCUE AT SEA September 2020 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Situation of Foreign Nationals (Including Asylum-Seekers, Refugees and Migrants)................................... 3 Humanitarian Situation ................................................................................................................................. 11 International Protection Needs of Foreign Nationals Departing from/through Libya .................................. 16 Libya as a Country of Asylum ...................................................................................................................... 16 Designation of Libya as Safe Third Country ................................................................................................ 16 Designation of Libya as a Place of Safety for the Purpose of Disembarkation following Rescue at Sea ... 17 Introduction 1. This position supersedes and replaces UNHCR’s guidance on foreign nationals in Libya contained in the Position on Returns to Libya – Update II of September 2018; however, UNHCR guidance in relation to Libyan nationals and habitual residents as provided in the September