US-India Homeland Security Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2013-2014 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT(%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 209143 0.005310639 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 775695 0.019696744 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1618569 0.041099322 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 482558 0.012253297 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 534260 0.013566134 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 776771 0.019724066 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 201424 0.005114635 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 6550 0.00016632 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 1417145 0.035984687 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 546688 0.01388171 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 154046 0.003911595 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 18771 0.00047664 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 69244 0.00175827 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 153965 0.003909538 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 65899 0.001673333 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 172484 0.00437978 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 67128 0.00170454 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410114 STATE TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) -

"Online" Application the Candidates Need to Logon to the Website and Click Opportunity Button and Proceed As Given Below

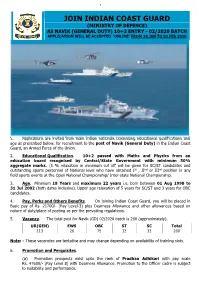

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2020 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 26 JAN TO 02 FEB 2020 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with Maths and Physics from an education board recognised by Central/State Government with minimum 50% aggregate marks. (5 % relaxation in minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports personnel of National level who have obtained Ist , IInd or IIIrd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Inter-state National Championship. 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. born between 01 Aug 1998 to 31 Jul 2002 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits. On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay of Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the prevailing regulations. 5. Vacancy. The total post for Navik (GD) 02/2020 batch is 260 (approximately). UR(GEN) EWS OBC ST SC Total 113 26 75 13 33 260 Note: - These vacancies are tentative and may change depending on availability of training slots. 6. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist upto the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. -

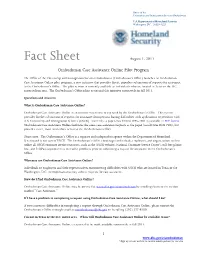

Ombudsman Case Assistance Online Pilot Program Fact Sheet

Office of the Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman U.S. Department of Homeland Security Washington, D.C. 20528-1225 Fact Sheet August 1, 2011 Ombudsman Case Assistance Online Pilot Program The Office of the Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman (Ombudsman’s Office) launches its Ombudsman Case Assistance Online pilot program, a new initiative that provides direct, paperless submission of requests for assistance to the Ombudsman’s Office. The pilot version is currently available to individuals who are located in Texas or the D.C. metropolitan area. The Ombudsman’s Office plans to expand this initiative nationwide in fall 2011. Questions and Answers: What is Ombudsman Case Assistance Online? Ombudsman Case Assistance Online is an Internet-based system operated by the Ombudsman’s Office. This system provides for the submission of requests for assistance from persons having difficulties with applications or petitions with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). Currently, a paper-based Form DHS-7001 is available in PDF format. Ombudsman Case Assistance Online facilitates the same case assistance requests as the paper-based Form DHS-7001, but provides easier, more immediate access to the Ombudsman’s Office. Please note: The Ombudsman’s Office is a separate and independent agency within the Department of Homeland Securityand is not part of USCIS. The Ombudsman’s Office encourages individuals, employers, and organizations to first utilize all USCIS customer service resources, such as the USCIS website, National Customer Service Center’s toll-free phone line, and InfoPass appointments to resolve problems prior to submitting a request for assistance to the Ombudsman’s Office. -

Fulfilling His Purpose Impact Beyond Graduation from the EDITOR G R a C E M a G a Z I N E Volume 29 | Number 2

The Quarterly Magazine of Grace College and Seminary Summer 2009 Fulfilling His Purpose Impact Beyond Graduation FROM THE EDITOR G r a c e M a G a z i n e Volume 29 | number 2 So, what are your plans? Published four times a year for alumni and friends of Grace College and Seminary. If graduates had a dollar for each time they were asked that question, it would i nstitutional Mission probably relieve a lot of job-hunting stress. And this year’s dismal job market only Grace is an evangelical Christian community of higher education which applies biblical adds to the uncertainty that graduates feel as they seek to find their place in the world values in strengthening character, sharpening beyond campus. competence, and preparing for service. P r e s i d e n t However, there is no shortage of information available on finding employment, Ronald E. Manahan, MDiv 70, ThM 77, ThD 82 choosing a career, or even fulfilling purpose in life. The Internet, bookstores, seminars, counselors—all provide resources to help launch a graduate into the working world. d irector of Marketin G a n d c o mm u n i c at i o n Joel Curry, MDiv 92 But as you glance through titles and topics, you begin to see a trend. Much of the information focuses on you. Statements such as, “The answers lie within you” or e d i t o r Judy Daniels, BA 72 “Create your purpose,” seem to be common. One source claims to help you find your e-mail: [email protected] purpose in life in 20 minutes. -

Project Division

MAGAL SECURITY SYSTEMS Focused Solutions for the World’s Security Needs Kobi Vinokur, CFO March 2020 1 / SAFE HARBOR/ Statements concerning Magal Security’s business outlook or future economic performance, product introductions and plans and objectives related thereto, and statements concerning assumptions made or expectations as to any future events, conditions, performance or other matters, are "forward-looking statements'' as that term is defined under U.S. federal securities laws. Forward-looking statements are subject to various risks, uncertainties and other factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from those stated in such statements. These risks, uncertainties and factors include, but are not limited to: the effect of global economic conditions in general and conditions affecting Magal Security’s industry and target markets in particular; shifts in supply and demand; market acceptance of new products and continuing products' demand; the impact of competitive products and pricing on Magal Security’s and its customers' products and markets; timely product and technology development/upgrades and the ability to manage changes in market conditions as needed; the integration of acquired companies, their products and operations into Magal Security’s business; and other factors detailed in Magal Security’s filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Magal Security assumes no obligation to update the information in this release. Estimated growth rates and other predictive statements represent Magal Security’s assumptions and expectations in light of currently available information. Estimated growth rates and other predictive statements, are based on industry trends, circumstances involving clients and other factors, and they involve risks, variables and uncertainties. -

Lower School Family Handbook

Lower School Family Handbook Table of Contents Mission and Vision 5 Grace School Belief Statements 5 Lower School Hours 5 Extended Care 5-6 Important School Numbers 6 Accreditation 6 Liability Insurance 6 Registration and Enrollment Requirements 6-7 Class Groupings 7 Daily Schedule 7 Program and Teaching Staff Qualifications 7 Supervision of Students 8 Attendance 8-9 Curriculum and Philosophy 9 Assessment 9-10 Homework 10-11 Student Organization 11 Grading 11-12 Promotion to the Next Grade 12-13 Parent Communication 13 Communication and Social Media Guidelines 13-15 Car Pool 15 Emergency Sheet 15-16 Health and Safety Regulations 16-17 Illness or Injury at School 17 Health Communication Procedures 17-20 Dress Code 20-25 Snack and Lunch 25 Parties and Celebrations 25 Lower School Handbook • 3 • Parent Volunteer and Involvement Opportunities 26 Discipline and Guidance 26-29 Special Accommodations for Children 30 Dismissal 30 Campus Security/Emergencies 30-32 Counseling Services 32 Grievance Procedure 32 Athletics . 35-42 Philosophy 35 Team Placement Guidelines 35 Playing Time Guidelines 36 Practice Schedules 36 General Guidelines 37-38 Responsibilites of a Grace School Athletic Parent 38 Responsibilities of a Grace School Athlete 38-39 Discipline Guidelines 39 Phases of Consequences 39 Specifics on Each Sport 40-42 Fall Season 40 Winter Season 40-41 Spring Season 41-42 Greater Houston Athletic Conference 42 • 4 • GRACE SCHOOL Mission and Vision The mission of Grace School is to provide a rigorous educational program that embraces the teachings -

Join Indian Coast Guard (Ministry of Defence) As Navik (General Duty) 10+2 Entry - 02/2018 Batch Application Will Be Accepted ‘Online’ from 24 Dec 17 to 02 Jan 18

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2018 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 24 DEC 17 TO 02 JAN 18 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age, as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with 50% marks aggregate in total and minimum 50% aggregate in Maths and Physics from an education board recognized by Central/State Government. (5 % relaxation in above minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports person of National level who have obtained 1st, 2nd or 3rd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Interstate National Championship. This relaxation will also be applicable to the wards of Coast Guard uniform personnel deceased while in service). 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. between 01 Aug 1996 to 31 Jul 2000 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits:- On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the regulation enforced time to time. 5. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist up to the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. 47600/- (Pay Level 8) with Dearness Allowance. -

Smart Border Management: Indian Coastal and Maritime Security

Contents Foreword p2/ Preface p3/ Overview p4/ Current initiatives p12/ Challenges and way forward p25/ International examples p28/Sources p32/ Glossary p36/ FICCI Security Department p38 Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security September 2017 www.pwc.in Dr Sanjaya Baru Secretary General Foreword 1 FICCI India’s long coastline presents a variety of security challenges including illegal landing of arms and explosives at isolated spots on the coast, infiltration/ex-filtration of anti-national elements, use of the sea and off shore islands for criminal activities, and smuggling of consumer and intermediate goods through sea routes. Absence of physical barriers on the coast and presence of vital industrial and defence installations near the coast also enhance the vulnerability of the coasts to illegal cross-border activities. In addition, the Indian Ocean Region is of strategic importance to India’s security. A substantial part of India’s external trade and energy supplies pass through this region. The security of India’s island territories, in particular, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, remains an important priority. Drug trafficking, sea-piracy and other clandestine activities such as gun running are emerging as new challenges to security management in the Indian Ocean region. FICCI believes that industry has the technological capability to implement border management solutions. The government could consider exploring integrated solutions provided by industry for strengthening coastal security of the country. The FICCI-PwC report on ‘Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security’ highlights the initiatives being taken by the Central and state governments to strengthen coastal security measures in the country. -

Government of India Ministry of Home Affairs Rajya Sabha

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS RAJYA SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO.*318 TO BE ANSWERED ON THE 17TH DECEMBER, 2014/AGRAHAYANA 26, 1936 (SAKA) STEPS TO AVOID ATTACKS LIKE 26/11 *318. SHRIMATI RAJANI PATIL: Will the Minister of HOME AFFAIRS be pleased to state the details of steps taken by Government to avoid attacks like 26/11 in the country by foreign elements, particularly keeping in view the threats being received from terrorist groups from foreign countries? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (SHRI HARIBHAI PARATHIBHAI CHAUDHARY) A Statement is laid on the Table of the House. ******* -2- STATEMENT REFERRED TO IN RAJYA SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO.*318 FOR 17.12.2014. Public Order and Police are State subjects. Thus, the primary responsibility to address these issues remains with the State Governments. However, the Central Government is of the firm belief that combating terrorism is a shared responsibility of the Central and the State Governments. In order to deal with the menace of extremism and terrorism, the Government of India has taken various measures which, inter-alia, include augmenting the strength of Central Armed Police Forces; establishment of NSG hubs at Chennai, Kolkata, Hyderabad and Mumbai; empowerment of DG, NSG to requisition aircraft for movement of NSG personnel in the event of any emergency; tighter immigration control; effective border management through round the clock surveillance & patrolling on the borders; establishment of observation posts, border fencing, flood lighting, deployment of modern and hi- tech surveillance equipment; upgradation of Intelligence setup; and coastal security by way of establishing marine police stations along the coastline. -

Threnody Amy Fitzgerald Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College English Honors Projects English Department 2012 Threnody Amy Fitzgerald Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Fitzgerald, Amy, "Threnody" (2012). English Honors Projects. Paper 21. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors/21 This Honors Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Threnody By Amy Fitzgerald English Department Honors Project, May 2012 Advisor: Peter Bognanni 1 Glossary of Words, Terms, and Institutions Commissie voor Oorlogspleegkinderen : Commission for War Foster Children; formed after World War II to relocate war orphans in the Netherlands, most of whom were Jewish (Dutch) Crèche : nursery (French origin) Fraulein : Miss (German) Hervormde Kweekschool : Reformed (religion) teacher’s training college Hollandsche Shouwberg : Dutch Theater Huppah : Jewish wedding canopy Kaddish : multipurpose Jewish prayer with several versions, including the Mourners’ Kaddish KP (full name Knokploeg): Assault Group, a Dutch resistance organization LO (full name Landelijke Organasatie voor Hulp aan Onderduikers): National Organization -

International Terrorism -- Sixth Committee

Please check against delivery STATEMENT BY SHRI ARON JAITLEY HONOURABLE MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT AND MEMBER OF THE INDIAN DELEGATION ON AGENDA ITEM 110 "MEASURES TO ELIMINATE INTERNATIONAL TERRORISM" ATTHE SIXTH COMMITTEE OF THE 68TH SESSION OF THE UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY New York 8 October 2013 Permanent Mission of India to the United Nations 235 East 43rd Street, New York, NY 10017 • Tel: (212) 490-9660 • Fax: (212) 490-9656 E-Mail: [email protected] • [email protected] Mr. Chairman, At the outset, I congratulate you for your election as the Chairperson of the Sixth Committee. I also congratulate other members of the Bureau on their election. I assure you of full cooperation and support of the Indian delegation during the proceedings of the Committee. I would also like to thank the Secretary-General for his report A/68/180 dated 23 July 2013 entitled "Measures to eliminate international terrorism". Mr. Chairman, The international community is continuously facing a grave challenge from terrorism. It is a scourge that undermines peace, democracy and freedom. It endangers the foundation of democratic societies. Terrorists are waging an asymmetric warfare against the international community, and are a major most threat to the international peace and security. India holds the firm view that no cause whatsoever or grievance could justify terrorism. India condemns terrorism in all its forms and manifestations, including those in which States are directly or indirectly involved, including the State-sponsored cross-border terrorism, and reiterates the call for the adoption of a holistic approach that ensures zero-tolerance towards terrorism. Mr. -

Water Sector Cybersecurity Brief for States

WATER SECTOR CYBERSECURITY BRIEF FOR STATES Introduction Implementing cybersecurity best practices is critical for water and wastewater utilities. Cyber-attacks are a growing threat to critical infrastructure sectors, including water and wastewater systems. Many critical infrastructure facilities have experienced cybersecurity incidents that led to the disruption of a business process or critical operation. Cyber Threats to Water and Wastewater Systems Cyber-attacks on water or wastewater utility business enterprise or process control systems can cause significant harm, such as: • Upset treatment and conveyance processes by opening and closing valves, overriding alarms or disabling pumps or other equipment; • Deface the utility’s website or compromise the email system; • Steal customers’ personal data or credit card information from the utility’s billing system; and • Install malicious programs like ransomware, which can disable business enterprise or process control operations. These attacks can: compromise the ability of water and wastewater utilities to provide clean and safe water to customers, erode customer confidence, and result in financial and legal liabilities. Benefits of a Cybersecurity Program The good news is that cybersecurity best practices can be very effective in eliminating the vulnerabilities that cyber-attacks exploit. Implementing a basic cybersecurity program can: • Ensure the integrity of process control systems; • Protect sensitive utility and customer information; • Reduce legal liabilities if customer or employee personal information is stolen; and • Maintain customer confidence. Challenges for Utilities in Starting a Cybersecurity Program Many water and wastewater utilities, particularly small systems, lack the resources for information technology (IT) and security specialists to assist them with starting a cybersecurity program. Utility personnel may believe that cyber-attacks do not present a risk to their systems or feel that they lack the technical capability to improve their cybersecurity.