“Swamp Cedars” of Spring Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Description and Correlation of Geologic Units, Cross

Plate 2 UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Utah Geological Survey Bulletin 135 a division of Hydrogeologic Studies and Groundwater Monitoring in Snake Valley and Utah Department of Natural Resources Adjacent Hydrographic Areas, West-Central Utah and East-Central Nevada DESCRIPTION OF GEOLOGIC UNITS SOURCES USED FOR MAP COMPILATION UNIT CORRELATION AND UNIT CORRELATION HYDROGEOLOGIC Alluvial deposits – Sand, silt, clay and gravel; variable thickness; Holocene. Qal MDs Lower Mississippian and Upper Devonian sedimentary rocks, undivided – Best, M.G., Toth, M.I., Kowallis, B.J., Willis, J.B., and Best, V.C., 1989, GEOLOGIC UNITS UNITS Shale; consists primarily of the Pilot Shale; thickness about 850 feet in Geologic map of the Northern White Rock Mountains-Hamlin Valley area, Confining Playa deposits – Silt, clay, and evaporites; deposited along the floor of active Utah, 300–400 feet in Nevada. Aquifers Qp Beaver County, Utah, and Lincoln County, Nevada: U.S. Geological Survey Units playa systems; variable thickness; Pleistocene through Holocene. Map I-1881, 1 pl., scale 1:50,000. D Devonian sedimentary rocks, undivided – Limestone, dolomite, shale, and Holocene Qal Qsm Qp Qea Qafy Spring and wetland related deposits – Clay, silt, and sand; variable thickness; sandstone; includes the Guilmette Formation, Simonson and Sevy Fritz, W.H., 1968, Geologic map and sections of the southern Cherry Creek and Qsm Quaternary Holocene. Dolomite, and portions of the Pilot Shale in Utah; thickness about 4400– northern Egan Ranges, White Pine County, Nevada: Nevada Bureau of QTcs 4700 feet in Utah, 2100–4350 feet in Nevada. Mines Map 35, scale 1:62,500. Pleistocene Qls Qlm Qlg Qgt Qafo QTs QTfs Qea Eolian deposits – Sand and silt; deposited along valley floor margins, includes Hintze, L.H., 1963, Geologic map of Utah southwest quarter, Utah Sate Land active and vegetated dunes; variable thickness; Pleistocene through S Silurian sedimentary rocks, undivided – Dolomite; consists primarily of the Board, scale 1:250,000. -

The Origin and Evolution of the Southern Snake Range Decollement, East Central Nevada Allen J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Dayton University of Dayton eCommons Geology Faculty Publications Department of Geology 2-1993 The Origin and Evolution of the Southern Snake Range Decollement, East Central Nevada Allen J. McGrew University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/geo_fac_pub Part of the Geology Commons, Geomorphology Commons, Geophysics and Seismology Commons, Glaciology Commons, Hydrology Commons, Other Environmental Sciences Commons, Paleontology Commons, Sedimentology Commons, Soil Science Commons, Stratigraphy Commons, and the Tectonics and Structure Commons eCommons Citation McGrew, Allen J., "The Origin and Evolution of the Southern Snake Range Decollement, East Central Nevada" (1993). Geology Faculty Publications. 29. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/geo_fac_pub/29 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Geology at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. TECTONICS, VOL. 12, NO. 1, PAGES 21-34, FEBRUARY 1993 THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF INTRODUCTION THE SOUTHERN SNAKE RANGE The origin,kinematic significance and geometrical evolu- DECOLLEMENT, EAST CENTRAL tion of shallowlyinclined normal fault systemsare NEVADA fundamentalissues in extensionaltectonics. Regionally extensivefaults that juxtapose nonmetamorphic sedimentary Allen J. McGrew1 rocksin theirhanging walls againstplastically deformed Departmentof Geology,Stanford University, Stanford, crystallinerocks in their footwallscommand special California attentionbecause they offer rare opportunitiesto characterize kinematiclinkages between contrasting structural levels. Thesefaults, commonly known as detachmentfaults, are the Abstract.Regional and local stratigraphic, metamorphic, subjectsof muchcontroversy. -

AND SCHELL CREEK DIVISIONS of the James O. Klemmedson

An Inventory of Bristlecone Pine in the Snake, Mount Moriah, Ward Mountain, and Schell Creek Divisions of the Humboldt National Forest Authors Klemmedson, James O.; Beasley, R. Scott Publisher Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 02/10/2021 17:39:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/302516 Report AN INVENTORY OF BRISTLECONE PINE IN THE SNAKE, MOUNT MORIAH, WARD MOUNTAIN, AND SCHELL CREEK DIVISIONS OF THE HUMBOLDT NATIONAL FOREST Prepared by James O. Klemmedson and R. Scott Beasley* Submitted to REGIONAL FORESTER, U.S. FOREST SERVICE OGDEN, UTAH in accordance with a COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT between the FOREST SERVICE and LABORATORY OF TREE-RING RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA for A JOINT INVENTORY AND DENDROCHRONOLOGICAL STUDY OF BRISTLECONE PINE * Department of Watershed Management, University of Arizona INTRODUCTION Bristlecone pine, Pinus aristata Engeim., is a species which inhabits high altitudes of the mountainous southwestern United States. It occurs from the Front Range of Colorado through Utah, northern New Mexico and Arizona to the White Mountains of California along the Nevada border in the west. Bristlecone pine commonly occurs in small open groves on arid slopes, but it also grows in association with limber and ponderosa pines, white fir, Douglas - fir, and Engelmann spruce, generally above the 8000 -foot level. This tree has little economic value as a timber species, but does provide a protective and beautifying cover to the landscape. A newly -acquired interst in bristlecone pine stems from the discovery that these trees reach tremendous ages. -

High-Elevation Five Needle Pine Cone Collections in California and Nevada

High-elevation white pine cone collections from the Great Basin of Nevada, California, & Utah on National Forest, Bureau of Land Management, National Park, and State lands, 2009 – 2013. Collected 40-50 cones/tree. 2009 (all on NFS land): 3 sites # trees Schell Creek Range, Cave Mtn., NV Pinus longaeva 100 Spring Mtns., Lee Canyon, NV Pinus longaeva 100 White Mtns., Boundary Peak, NV Pinus longaeva 100 2010 (all on NFS land except as noted): 7 sites Carson Range, Mt. Rose, NV Pinus albicaulis 23 Hawkins Peak, CA Pinus albicaulis 26 Luther Creek, CA Pinus lambertiana 15 Monitor Pass, CA Pinus lambertiana 25 Pine Forest Range, NV [BLM] Pinus albicaulis 20 Sweetwater Mtns., NV Pinus albicaulis 20 Wassuk Range, Corey Pk., NV [BLM] Pinus albicaulis 25 2011 (all on NFS land except as noted): 13 sites Fish Creek Range, NV [BLM] Pinus flexilis 25 Fish Creek Range, NV [BLM] Pinus longaeva 25 Grant Range, NV Pinus flexilis 25 Highland Range, NV [BLM] Pinus longaeva 25 Independence Mtns., NV Pinus albicaulis 17 Jarbidge Mtns., NV Pinus albicaulis 25 Pequop Mtns., NV [BLM] Pinus longaeva 25 Ruby Mtns., Lamoille Canyon, NV Pinus albicaulis 25 Ruby Mtns., Lamoille Canyon, NV Pinus flexilis 20 Schell Creek Range, Cave Mtn., NV Pinus flexilis 25 Sweetwater Mtns., NV Pinus flexilis 25 White Pine Range, Mt. Hamilton, NV Pinus flexilis 25 White Pine Range, Mt. Hamilton, NV Pinus longaeva 25 2012 (all on NFS land except as noted): 9 sites Black Mountain, Inyo NF, CA Pinus longaeva 23 Carson Range, LTBMU, NV Pinus albicaulis 25 Egan Range, Toiyabe NF, NV Pinus longaeva 25 Emma Lake, Toiyabe NF, CA Pinus albicaulis 25 Happy Valley, Fishlake NF, UT Pinus longaeva 25 Inyo Mtns., Tamarack Canyon, CA Pinus longaeva 25 Leavitt Lake, Toiyabe NF, CA Pinus albicaulis 25 Mt. -

Monsoon Passage Fact Sheet

Monsoon Passage Fact Sheet Safe haven stepping stones from the Mojave Desert to the Northern Great Basin East Pass a few years after a fire in the Clover Mountains of the southern Great Basin looking down into the Mojave’s Tule Desert © Louis Provencher/TNC Monsoon Passage The connected mountain ranges and wet valley bottoms of this natural highway provide desert tortoises, bighorn sheep, Cooper’s hawk, mule deer and other species escape routes from growing climate impacts, allowing them to find new homes where they can thrive. The region's name comes from being at the western edge of the summer monsoons that provide needed eastern-facing moisture to buffer rising temperatures and a pathway for species moving north. Imagine populations of raptors, small carnivores, small mammals, mule deer, bighorn sheep, passerine birds, insects, and plant species pushed northward or up and around mountains by warming temperatures and changes in precipitation patterns. Non-migratory species flow from the hot Mojave Desert ecoregion to the cooler Columbia Plateau ecoregion passing through the entirety of the Great Basin ecoregion is not easily guaranteed. There are less than five corridors of passably connected mountains ranges and wet valley bottoms that fully allow species movement within a viable thermal environment that may be viewed as steppingstones of safe havens. The Nevada Chapter is proposing one such thermal corridor in eastern Nevada titled Monsoon Passage. The corridor follows the Nevada-Utah border and is mostly in Nevada. For those familiar -

Structural Geology of the Confusion Range, West-Central Utah

Structural Geology of the Confusion Range, West-Central Utah GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 971 Structural Geology of the Confusion Range, West-Central Utah By Richard K. Hose GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 971 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1977 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR THOMAS S. KLEPPE, Strrtlory GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Dirator Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Hose, Richard Kenneth, 1920- Structural geology of the Confusion Range, west-central Utah. (Geological Survey Professional Paper 971) Bibliography: p. 9. Supt. of Docs. no.: I 19.16:971 1. Geology-Utah-Confusion Range. I. Title. II. Series: United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 971. QE170.C59H67 551.8'09792'45 76-608301 For ~ale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office \Vashington, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-02923-5 CONTENTS Page 1\bstract ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 1 Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Structural history ______________________________________________________________________ 1 Late Mesozoic to early Cenozoic orogeny ------------------------------------------------ 3 Structures within the structural trough ------------------------------------------------ 3 Low-angle faults ________________________________________ -------------------------- 3 Evidence for the higher decollement ------------------------------------------------ 4 Evidence -

Spring Valley (Updated 2014)

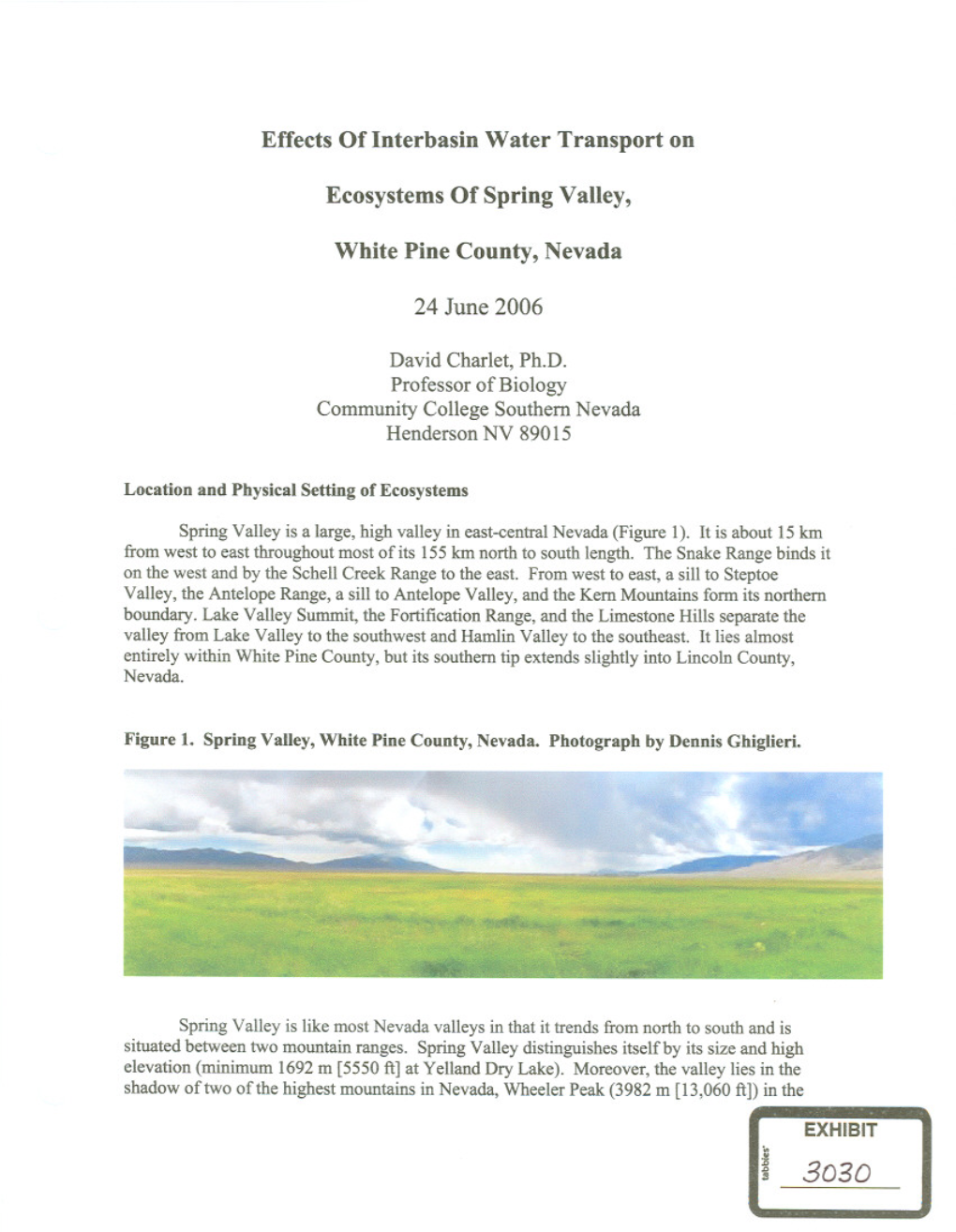

Site Description Spring Valley (updated 2014) Geologic setting: Spring Valley is located approximately 40 km towards the east of Ely, Nevada between the Schell Creek Range on its western boundary and the Snake Mountain Range on its eastern boundary. The Snake Range is a north trending mountain range and extends approximately 150 km and is a classic example of a Cenozoic metamorphic core complex. The core complex is underlain by late Precambrian to Permian strata that were deposited on the western continental margin of North America (Gans and Miller, 1999). The Schell Creek Range has been a source of mineral bearing lodes in mining districts northeast of Ely, Nevada since 1870 and the rocks consists of Precambrian quartzite and phyllite cropping out on the eastern portion of the mountain range (Tingley and Castor, 1991). Geothermal features: D Henriod Ranch: At least two water wells in northern Spring Valley are reported to have temperatures somewhat higher than expected. The 183-m-deep flowing Lawrence Henroid well, in Sec. 31, T23N, R66E, has a temperature of 31.6°C. The nearby Hans L. Anderson well is also artesian, 317 m deep, and has a temperature of 26°C (Great Basin Groundwater Geochemical Database). The Cedars: The Cedars wells are located approximately 65 km towards the southeast of Ely, Nevada, and have a temperature of 23.5°C (Great Basin Groundwater Geochemical Database). Leasing information: N/A Bibliography: Gans, P.B., Miller, E.L., and Lee, J., 1999, Geologic map of the Spring Mountain quadrangle, Nevada and Utah: Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology Field Studies Map 18, scale 1:24,000 Great Basin Groundwater Geochemical Database, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology: <http://www.nbmg.unr.edu/Geothermal/GeochemDatabase.html>. -

Mineral Resources of the Marble Canyon Wilderness Study Area, White Pine County, Nevada, and Millard County, Utah

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) Depository) 1990 Mineral Resources of the Marble Canyon Wilderness Study Area, White Pine County, Nevada, and Millard County, Utah United States Geological Survey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Recommended Citation United States Geological Survey, "Mineral Resources of the Marble Canyon Wilderness Study Area, White Pine County, Nevada, and Millard County, Utah" (1990). All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository). Paper 221. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs/221 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS u.s. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Bureau of Land Ma:l8gement Wilderness Study Area The Fe<!=! Land Policy and Management Act (Publio Law 94-579, October 21, 1976) requires MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE MARBLE CANYON the U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Bureau of Mines to conduct mineral surveys on ccnain WlLDERNEf,s STUDY AREA, WHITE PINE COUNTY, NEVADA, AND MILLARD COUNTY, UTAH areas to determine !he rninerrJ values. if any, that may be prcsenL Results must be made By availabl. to the public and be submincd to the President and the Congress. This report presents Michael F. Digglesl• Gary A. -

Bristlecone Wilderness Area

µ Bristlecone Wilderness Area 0 672000 673000 674000 675000 676000 677000 678000 679000 680000 681000 682000 683000 684000 685000 686000 687000 688000 0 0 8 7 3 4 0 0 0 7 7 3 4 0 0 0 6 7 3 4 0 0 0 5 7 3 4 0 0 0 4 7 3 4 0 0 0 3 7 3 4 0 0 0 2 7 3 4 0 0 0 1 7 3 4 0 0 0 0 7 3 4 0 0 0 9 6 3 4 0 0 0 8 6 3 4 0 0 0 7 6 3 4 0 0 0 6 6 3 4 0 0 0 5 6 3 4 0 0 0 4 6 3 4 0 0 0 3 6 3 4 0 0 0 2 6 3 4 0 0 0 1 6 3 4 0 0 0 0 6 3 4 0 0 0 9 5 3 4 0 0 0 8 5 3 4 0 0 0 7 5 3 4 1:24,000 Maps Legend Steptoe Ranch ¤£93 Wilderness Area McGill McGill 0 0.5 1 2 Lusetti Canyon Miles 490 50 1:65,000 ¤£ No Warranty is made by the Bureau of Land Ely BLM Field Office Management as to the accuracy, reliability, Ely For more information call: Ruth or completeness of these data for individual (775) 289-1800 1:100,000 Maps: use or aggregate use with other data. Ely & Kern Mountains January 2007 Sheet BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT ELY FIELD OFFICE (Tel: 775-289-1800) HC Box 33500, Ely, Nevada 89301-9408 Bristlecone Wilderness Area 14,095 acres Elevation: 7,380 – 9,859 feet Location The Bristlecone Wilderness Area is located in central White Pine County, approximately 5 miles due west of McGill, Nevada, or about 10 miles north of Ely, Nevada. -

Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act of 1998, As Amended

Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act of 1998, as Amended Capital Improvements - Project Summary Round 17 Project Name: Bristlecone Recreation Area and Summit Trailhead Reconstruction Round: 17 Tab #: 1 County: White Pine Location: The project area is in the Great Basin National Park, in east central Nevada, near Baker Nevada, at the terminus of the Wheeler Peak Scenic Drive. The trailhead and is at 9,886 feet and trail continues up to Stella Lake, at 10,420 feet. Nominating Agency/Entity: NPS Funding Requested: $2,371,575 Project Description: The Bristlecone Recreation Area at 9,886 feet in Great Basin National Park was constructed almost 50 years ago and has seen minimal changes or upgrades over the life of the project. Great Basin proposes to: convert the underutilized amphitheater into a day-use picnic area; upgrade the trailhead and improve signage, wayside exhibits, and kiosks; reconstruct the parking area to improve accessability; reconstruct theSummit Peak Trail System and trailhead; reconstruct the water line to comply with Nevada State Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) requirements; the half mile Accessible Island Forest Nature Trail will be upgraded. This proposal corrects a variety of impacts to natural resources due to increased visitation and engages visitors protecting the resources of the area. SNPLMA, Capital Improvements Wednesday, September 20, 2017 Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act of 1998, as Amended Capital Improvements - Project Summary Round 17 Project Name: Cold Spring Restoration and UCS Trail Construction Round: 17 Tab #: 2 County: Nye Location: The project is in the Upper Carson Slough (UCS) of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Nye County, Nevada. -

Lincoln County Public Lands Policy Plan

The Lincoln County Public Lands Policy Plan 2010 Amended 2015 2010 Lincoln County Public Lands Policy Plan; as amended 2015 Table of Contents Page I. PLAN BACKGROUND…………………………………………………………...... 4 Location………………………………………………………………………… 4 II. PLAN PURPOSE………………………………………………………………….. 8 III. PROCESS………………………………………………………………………… 10 IV. ENVIRONMENT………………………………………………………………… 11 Climate……….……………………………………………………………....... 11 Geologic and Geographic Features…..……………………………........ 11 Hydrology and Groundwater Resources……………………………… 12 Vegetation…………………………………………………………………..... 14 Land Uses........................................................................................ 17 Transportation System.................................................................... 17 Agricultural and Natural Resources................................................. 17 Wildlife………………………………………………………………………..... 18 V. CULTURE AND HISTORY……………………………………………………..... 19 Prehistoric Settlement..................................................................... 19 Historic Settlement.......................................................................... 19 Contemporary Settlement............................................................... 20 Recreation…………………………………………………………………..... 21 Fiscal and Economic Conditions…………………..……………………... 24 VI. POLICIES………………………………………………………………………..... 25 1. Plan Implementation, Agency Coordination and Local Voice… 25 2. Management of Public Lands………………..……………………….. 28 3. Federal Land Transactions...………………………………………….. 29 4. Agriculture and Livestock -

Rock Aquifer System, White Pine County, Nevada, and Adjacent Areas in Nevada and Utah

Prepared in cooperation with the Bureau of Land Management Water-Level Surface Maps of the Carbonate-Rock and Basin-Fill Aquifers in the Basin and Range Carbonate- Rock Aquifer System, White Pine County, Nevada, and Adjacent Areas in Nevada and Utah Scientific Investigations Report 2007–5089 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Water-Level Surface Maps of the Carbonate- Rock and Basin-Fill Aquifers in the Basin and Range Carbonate-Rock Aquifer System, White Pine County, Nevada, and Adjacent Areas in Nevada and Utah By J.W. Wilson Prepared in cooperation with the Bureau of Land Management Scientific Investigations Report 2007-5089 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Wilson, J.W., 2007, Water-level surface maps of the carbonate-rock and basin-fill aquifers in the Basin and Range carbonate-rock aquifer system, White Pine County, Nevada, and adjacent areas in Nevada and Utah: U.S.