Addressing Women's Poverty in Birmingham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warding Arrangements for Legend Ladywood Ward

Newtown Warding Arrangements for Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Ward Legend Nechells Authority boundary Final recommendation North Edgbaston Ladywood Bordesley & Highgate Edgbaston 0 0.1 0.2 0.4 Balsall Heath West Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Bournville & Cotteridge Allens Cross Warding Arrangements for Longbridge & West Heath Ward Legend Frankley Great Park Northfield Authority boundary King's Norton North Final recommendation Longbridge & West Heath King's Norton South Rubery & Rednal 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Warding Arrangements for Lozells Ward Birchfield Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Aston Handsworth Lozells Soho & Jewellery Quarter Newtown 0 0.05 0.1 0.2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Tyseley & Hay Mills Warding Balsall Heath West Arrangements for Moseley Ward Edgbaston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Sparkhill Moseley Bournbrook & Selly Park Hall Green North Brandwood & King's Heath Stirchley Billesley 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Hall Green South Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Perry Barr Stockland Green Warding Pype Hayes Arrangements for Gravelly Hill Nechells Ward Aston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Bromford & Hodge Hill Lozells Ward End Nechells Newtown Alum Rock Glebe Farm & Tile Cross Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Heartlands Bordesley & Highgate 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Bordesley Green Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Handsworth Aston Warding Lozells Arrangements for Newtown Ward Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Newtown Nechells Soho & Jewellery Quarter 0 0.075 0.15 0.3 Ladywood Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database Ladywood right 2016. -

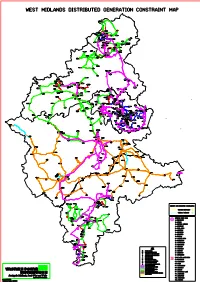

West Midlands Constraint Map-Default

WEST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP CONGLETON LEEK KNYPERSLEY PDX/ GOLDENHILL PKZ BANK WHITFIELD TALKE KIDSGROVE B.R. 132/25KV POP S/STN CHEDDLETON ENDON 15 YS BURSLEM CAULDON 13 CEMENT STAUNCH CELLARHEAD STANDBY F11 CAULDON NEWCASTLE FROGHALL TQ TR SCOT HAY STAGEFIELDS 132/ STAGEFIELDS MONEYSTONE QUARRY 33KV PV FARM PAE/ PPX/ PZE PXW KINGSLEY BRITISH INDUSTRIAL HEYWOOD SAND GRANGE HOLT POZ FARM BOOTHEN PDY/ PKY 14 9+10 STOKE CHEADLE C H P FORSBROOK PMZ PUW LONGTON SIMPLEX HILL PPW TEAN CHORLTON BEARSTONE P.S LOWER PTX NEWTON SOLAR FARM MEAFORD PCY 33KV C 132/ PPZ PDW PIW BARLASTON HOOKGATE PSX POY PEX PSX COTES HEATH PNZ MARKET DRAYTON PEZ ECCLESHALL PRIMARY HINSTOCK HIGH OFFLEY STAFFORD STAFFORD B.R. XT XT/ PFZ STAFFORD SOUTH GNOSALL PH NEWPORT BATTLEFIELD ERF GEN RUGELEY RUGELEY TOWN RUGELEY SWITCHING SITE HARLESCOTT SUNDORNE SOLAR FARM SPRING HORTONWOOD PDZ/ GARDENS PLX 1 TA DONNINGTON TB XBA SHERIFFHALES XU SHREWSBURY DOTHILL SANKEY SOLAR FARM ROWTON ROUSHILL TN TM 6 WEIR HILL LEATON TX WROCKWARDINE TV SOLAR LICHFIELD FARM SNEDSHILL HAYFORD KETLEY 5 SOLAR FARM CANNOCK BAYSTON PCD HILL BURNTWOOD FOUR ASHES PYD PAW FOUR ASHES E F W SHIFNAL BERRINGTON CONDOVER TU TS SOLAR FARM MADELEY MALEHURST ALBRIGHTON BUSHBURY D HALESFIELD BUSHBURY F1 IRONBRIDGE 11 PBX+PGW B-C 132/ PKE PITCHFORD SOLAR FARM I54 PUX/ YYD BUSINESS PARK PAN PBA BROSELEY LICHFIELD RD 18 GOODYEARS 132kV CABLE SEALING END COMPOUND 132kV/11kV WALSALL 9 S/STN RUSHALL PATTINGHAM WEDNESFIELD WILLENHALL PMX/ BR PKE PRY PRIESTWESTON LEEBOTWOOD WOLVERHAMPTON XW -

Homes in Birmingham Soar 58% in a Decade

Classification: Public @HalifaxBankNews FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Not a Brum deal: homes in Birmingham soar 58% in a decade The average house price in Birmingham increased 58% since 2009 First-time buyers face costs of more than £32,000 to get on the ladder Halifax will host a series of first-time buyer events in Birmingham, demystifying the process of buying a home The average house price in Birmingham increased 14% faster over the last decade than the rest of the West Midlands, new research from Halifax can reveal. With a strong history of supporting home buyers and movers in Birmingham, Halifax has used its own data to look at how the market has developed over the past 10 years. House price landscape The average house price in the city currently sits at £219,355, an increase of 58% since 2009. In the same period, the average price of a house in the West Midlands has increased by 44%, and 48% across the UK. The average home for a first-time buyer costs £181,880 The average home for a homemover costs £285,664 The most expensive street in a Birmingham postcode is Rising Lane in Solihull, where the average house price is £1,908,000 Ladywood Road and Bracebridge Road, both in Sutton Coldfield, have an average house price in excess of £1.5m NHBC data shows over 13,800 new homes were built in the West Midlands in 2018. Mortgages Mortgage payments in Birmingham take up nearly a third (31%) of disposable earnings (Q4 2018) Mortgage freedom day, the day in which a homeowner could have paid off their mortgage for the year if all their income went to it, was the 22nd April 2019. -

APPENDIX 1 Wards Where FPN's Are Issued Constituency Ward Apr May

APPENDIX 1 Wards where FPN's are issued Constituency Ward Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Total Edgbaston Bartley Green 0 0 0 0 Edgbaston 0 0 0 0 Harborne 0 0 0 0 Quinton 0 0 0 0 Erdington Erdington 0 1 0 1 Kingstanding 0 1 0 1 Stockland Green 0 0 2 2 Tyburn 0 1 1 2 Hall Green Hall Green 0 1 0 1 Moseley And Kings Heath 2 0 0 2 Sparkbrook 0 1 1 2 Springfield 0 0 0 0 Hodge Hill Bordesley Green 0 0 0 0 Hodge Hill 0 0 0 0 Shard End 1 4 0 5 Washwood Heath 1 0 0 1 Ladywood Aston 0 2 0 2 Ladywood 459 436 256 1,151 Nechells 5 3 0 8 Soho 5 1 0 6 Northfield Kings Norton 0 0 3 3 Longbridge 0 1 0 1 Northfield 2 0 0 2 Weoley 2 0 0 2 Perry Barr Handsworth Wood 0 0 1 1 Lozells And East Handsworth 0 1 1 2 Oscott 0 2 0 2 Perry Barr 1 0 1 2 Selly Oak Billesley 1 1 0 2 Bournville 0 0 1 1 Brandwood 0 0 0 0 Selly Oak 0 0 1 1 Sutton Coldfield Sutton Four Oaks 0 0 0 0 Sutton New Hall 0 0 0 0 Sutton Trinity 0 0 0 0 Sutton Vesey 0 0 0 0 Yardley Acocks Green 6 6 1 13 Sheldon 0 1 0 1 South Yardley 1 2 1 4 Stechford And Yardley North 1 0 0 1 Total 487 465 270 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1,222 APPENDIX 2 WARD OF PERSON RECEIVING FIXED PENALTY NOTICES BY CONSTITUENCY/WARD It is not possible to provide this information currently and will be provided in the coming weeks Constituency Ward Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Total Edgbaston BARTLEY GREEN 0 EDGBASTON 0 HARBORNE 0 QUINTON 0 Erdington ERDINGTON 0 KINGSTANDING 0 STOCKLAND GREEN 0 TYBURN 0 Hall Green HALL GREEN 0 MOSELEY AND KINGS HEATH 0 SPARKBROOK 0 SPRINGFIELD 0 Hodge Hill BORDESLEY GREEN -

Birmingham City Council Report of the Acting Service Director Regulation and Enforcement to the Licensing and Public Protection

BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL REPORT OF THE ACTING SERVICE DIRECTOR REGULATION AND ENFORCEMENT TO THE LICENSING AND PUBLIC PROTECTION COMMITTEE 10 APRIL 2019 ALL WARDS PROSECUTIONS AND CAUTIONS – FEBRUARY 2019 1. Summary 1.1 This report summarises the outcome of legal proceedings taken by Regulation and Enforcement during the month of February 2019. 2. Recommendation 2.1 That the report be noted. Contact Officer: Chris Neville, Acting Service Director Regulation and Enforcement Telephone: 0121 303 6111 E-Mail: [email protected] 1 3. Results 3.1 During the month of February 2019 the following cases were heard at Birmingham Magistrates Court, unless otherwise stated: ▪ Three Licensing cases were finalised resulting in fines of £320. 12 penalty points were issued and prosecution costs of £700 were awarded. No simple cautions were administered as set out in Appendix 1. ▪ 52 Environmental Health cases resulted in fines of £43,776. Prosecution costs of £16,270 were awarded. No simple cautions were administered as set out in Appendix 2. ▪ One Trading Standards case was finalised resulting in a fine of £1,800 and prosecution costs of £4,072 were awarded. A Forfeiture Order was granted in respect of 52 seized goods. No simple cautions were administered as set out in Appendix 3. ▪ Appendix 4 lists cases finalised by district in February 2019 and cases finalised by district April – February 2019. ▪ Appendix 5 lists the enforcement activity undertaken by the Waste Enforcement Team in April 2018 - January 2019. 4. Consultation 4.1 The Enforcement Policy that underpins the work identified in this report is approved by your Committee. -

Newtown, Oscott, Perry Barr, Soho, Oldbury

Equality and Diversity Strategy ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH C5206 GUJARATI Translation 1A ùf PYf #e `eQf WhMf¶\ R¶ÀPe]fHÌ T ]epFh ^A¶ef, Pef Ao¶Ue A¶[l YR¶R¶ Yfb]]e YeKf¶ #pCyfú C5206Wef\h ^Af¶ Pf]h A¶ef$ ½Zz¡PþTf #alò #eUf\e Kf¶z\þVeüT TpW[ U[ VeüT A¶[]e z]þTpPhFrench A¶[ef .................... TranslationC5206 1A BENGALI SiTranslation vous ne 1Apouvez pas lire le document ci-joint, veuillez demander Translation 1B C5206àIf youquelqu'un can not read qui the parle attached anglais document, d'appeler please get ce someone numéro who pour speaks obtenir EnglishPolish deto ring l’aidethis number ………………………… for help ………………………… ùf PYf #e `eQf WhMf¶\ R¶ÀPe]fHÌ T ]epFh ^A¶ef, Pef Ao¶Ue A¶[l YR¶R¶ Yfb]]e YeKf¶ #pCyfú TranslationåKAeM^Wef\h ^Af¶ svzuË Pf]h 1B1A A¶ef$ kAgj-pñAif^ ½Zz¡PþTf &U[ ÁpiM^ HÌOe]f\e pxew^ Kf¶z\þVeüT Mo pArel^, TpW[ U[ áMugòh VeüT A¶[]e ker^ z]þTpPhsAhAezù^r A¶[ef. jMù éver^jI blew^ pAer^M åmM kAõek^ if^ey^ ............................... -

North Edgbaston Ward Meeting Notes

NORTH EDGBASTON WARD MEETING NOTES WARD: North Edgbaston DATE:28 February 2019 VENUE: City Road Methodist Church, City Road START/FINISH TIMES: 7pm to 9.10pm COUNCILLOR Carl Rice NOs OF ATTENDEES: 70+ OFFICERS IN ATTENDANCE: APOLOGY – Councillor Sharon Thompson Sergeant Sandu, West Midlands Police Matt Smith, Private Rented Sector Team Craig Rowbottom, Development Planning Manager Pat Whyte, Community Support & Development Officer Kay Thomas, Community Governance Manager MATTERS DISCUSSED AT THE MEETING: 1. Police Update Sergeant Sandhu gave the following update; − Burglary, robbery & vehicle crime were local priorities − Queen Elizabeth Hospital and Birmingham University were within the Edgbaston team area and adversely affected figures − Information regarding Operation Park Safe provided − Residents asked to sign up to WMNow and encourage neighbours In response to residents questions, Sergeant Sandhu made the following comments; − Street Watch members to ask Sgt Lawless regarding the availability of personal alarms − The police did work with groups such as the Princes Trust and with schools. Sgt Sandhu undertook to investigate work in Summerfield Park and working with another agency to target those young people who would not engage with the police. − Procedure for arresting prostitutes explained – 3 street cautions had to be served in a 3 month period before an arrest could be FINAL, ND-C, ver 3 made. The police worked with the NHS outreach teams to help tackle the problem. Residents urged to provide information via 101 or the web chat. − Sgt Sandhu undertook to report back to the appropriate teams on issues raised regarding anti-social behaviour around the Reservoir − With regard bail hostels on Portland Road/Hagley Road there was only one authorised bail hostel in Edgbaston and it was well managed. -

Ladywood District Profile 2013 DRAFT

Ladywood District Profile 2013 DRAFT For more information: Richard Browne Partnership Manager Birmingham City Council Challenge Unit [email protected] Ladywood District Profile 2013 Contents Contents.........................................................................................................................................................2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................3 Background to the District.............................................................................................................................4 Resident Priorities..........................................................................................................................................5 SECTION 1: Who Lives Here?.........................................................................................................................6 SECTION 2: A Fair City: Tacking Deprivation and inequality and improving life chances ...........................10 Deprivation Profile...................................................................................................................................10 Child Poverty Profile ................................................................................................................................11 Fuel Poverty Profile..................................................................................................................................12 -

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 11 October 2018

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 11 October 2018 I submit for your consideration the attached reports for the North West team. Recommendation Report No. Application No / Location / Proposal Approve – Conditions 9 2018/06216/PA 5 Ferrers Close Sutton Coldfield Birmingham B75 6NG Erection of first floor extension to existing bungalow including increase in roof height, single storey side and rear extensions and first floor side dormer window Approve – Conditions 10 2018/01827/PA 134-138 Birmingham Road Sutton Coldfield Birmingham B72 1LY Demolition of existing buildings and erection of a care facility (Use Class C2) comprising 64-bed care home with associated car parking, access, landscaping and engineering works Approve – Conditions 11 2018/05477/PA 278 Birmingham Road Sutton Coldfield Birmingham B72 1DP Demolition of existing property and erection of 2no. detached dwellinghouses. Approve – Conditions 12 2018/06164/PA Coach House Building on land north-west of 1 Heather Court Gardens Sutton Coldfield Birmingham B74 2ST Conversion of detached coach house building to form a separate self-contained dwelling, provision of access route and removal of single storey block at rear to enlarge courtyard garden space. Page 1 of 1 Corporate Director, Economy Committee Date: 11/10/2018 Application Number: 2018/06216/PA Accepted: 27/07/2018 Application Type: Householder Target Date: 21/09/2018 Ward: Sutton Roughley 5 Ferrers Close, Sutton Coldfield, Birmingham, B75 6NG Erection of first floor extension to existing bungalow including increase in roof height, single storey side and rear extensions and first floor side dormer window Applicant: Mr D Hulson 5 Ferrers Close, Sutton Coldfield, Birmingham, B75 6NG Agent: Ben Parsons Design Limited 15 Moor Hall Drive, Sutton Coldfield, Birmingham, B75 6LP Recommendation Approve subject to Conditions 1. -

Making Ends Meet in Birmingham: Assessing the Impact of the Living Wage and Welfare Reform

Making ends meet in Birmingham: assessing the impact of the living wage and welfare reform Matt Padley and Laura Valadez Centre for Research in Social Policy Loughborough University with the Oxford Centre for Social Inclusion July 2015 © Loughborough University Published by the Centre for Research in Social Policy Loughborough University Leicestershire LE11 3TU ISBN 978 0946831 45 6 All rights reserved. Reproduction of this report by photocopying or electronic means for non-commercial purposes is permitted. Otherwise, no part of this report may be reproduced, adapted, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise without the prior written permission of Loughborough University. Contents Executive summary ...................................................................................... 3 1 Introduction .......................................................................................... 6 2 Austerity, welfare reform and the changing labour market: the UK context .................................................................................................. 8 2.1 The impact of austerity ....................................................................... 9 2.2 Welfare reform ................................................................................. 10 2.3 Changes in the labour market .......................................................... 11 3 The Birmingham context ...................................................................... 13 3.1 A city of -

Mapping of Race and Poverty in Birmingham

MAPPING OF RACE AND POVERTY IN BIRMINGHAM Alessio Cangiano – ESRC Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS, University of Oxford) II Table of contents Executive Summary p. 1 1. Introduction p. 3 2. Population characteristics and demographic dynamics p. 3 3. Geographical patterns of deprivation across the city p. 5 4. Socio-economic outcomes of different ethnic groups at ward level p. 7 4.1. Access to and outcomes in the labour market p. 7 4.2. Social and health conditions p. 9 4.3. Housing p.10 5. Public spending for benefits, services and infrastructures p.11 5.1. Benefit recipients p.11 5.2. Strategic planning p.11 6. Summary and discussion p.13 6.1. Data gaps p.13 6.2. Deprivation across Birmingham wards p.14 6.3. Deprivation across ethnic groups p.14 6.4. Relationship between poverty and ethnicity p.15 6.5. Consequences of demographic trends p.15 6.6. Impact of benefits and local government’s spending p.16 References p.17 III List of figures Figure 1 – Population by ethnic group, Birmingham mid-2004 (%) p.18 Figure 2.1 – Population change, Birmingham 2001-2004 (thousand) p.18 Figure 2.2 – Population change, Birmingham 2001-2004 (Index number, 2001=100) p.19 Figure 3 – Foreign-born population by ethnic group, Birmingham 2001 (%) p.19 Figure 4 – Age pyramids of the main ethnic groups in Birmingham, 2001 (%) p.20 Figure 5 – Distribution of the major ethnic groups across Birmingham wards, 2001 (absolute numbers) p.25 Figure 6 – Population by ethnic group in selected Birmingham wards, 2001 (%) p.27 Figure 7 – Indices of Deprivation, -

Ladywood District Jobs and Skills Plan 2015 Overview of Ladywood District1

Ladywood Jobs and Skills Plan Ladywood District Jobs and Skills Plan 2015 Overview of Ladywood District1 Ladywood District covers the majority of the city centre, along with inner city areas to the north and east. It is composed of 4 wards – Aston, Ladywood, Nechells and Soho. Much of the district experiences some very challenging conditions in terms of labour market status, with very high levels of unemployment. But this contrasts with the city centre area – the east of Ladywood ward, and the south-west of Nechells ward – where unemployment and deprivation levels are low. Ladywood has a younger age profile to the city centre with a higher proportion of under 40s and fewer over 45s. Overall the proportion of working age adults (70%) is well above the city average (64%). The proportion rises to 84% in Ladywood ward, but is close to the city average in the other 3 wards. There are 23,828 residents aged 18-24 equating to 19% of the population, compared to 12 % for Birmingham, driven at least in part by large numbers of students. The ethnic profile of the working age population in the district differs to that of the city, with a much lower proportion of white working age residents (32%) compared to the city average (59%). But this masks ward variations, with the proportion only 15% in Aston, 23% in Soho and 31% in Nechells wards, but much closer to the city average at 52% in Ladywood ward. Overall, the largest non-white groups are Pakistani (13%) and Black Caribbean (9%). The Pakistani group forms 20% of the population in Aston and 16% in Nechells and Soho wards ,but only 3% in Ladywood ward.