Changing Places: Stories of Innovation and Tenacity in Five Birmingham Neighbourhoods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Midlands Police and Crime Commissioner Register of Gifts And

West Midlands Police and Crime Commissioner Register of Gifts and Hospitality - Police and Crime Commissioner and Deputy Police and Crime Commissioner Note: This register contains details of declarations made by the PCC and DPCC and includes details of offers of gifts and hospitality not accepted Name Name of person or organisation Details of Gift or hospitality Estimate of value Date offer received Comments Funeral for Don Jones partner to Cllr Diana refreshments offered after Bob Jones Holl-Allen funeral £10.00 23/11/2012 declined passed to office staff for Bob Jones Harmeet Singh Bhakna Punjabi News Indian Sweets £5.00 23/11/2012 consumption Bob Jones Asian Business Forum Samosas and pakoras offered £7.00 28/11/2012 refreshments consumed Bob Jones Home office PCC welcome Buffet lunch provided £7.00 03/12/2012 refreshments consumed Bob Jones APPG on Polcing meeting Buffett and wine offered £10.00 03/12/2012 buffet consumed, wine declined Bob Jones Connect Public Affairs lunch buffet offered £12.00 04/12/2012 Buffet consumed Annual Karate Awards presentation Bob Jones evening food and drink offered £12.00 07/12/2012 food and drink declined invite to Brisitsh Police Symphony Orchestra BPSO accepted but ticket unavailable on Yvonne Mosquito Steria sponsors Proms night special £21.00 08/12/2012 the evening Gavin Chapman and John Torrie - Steria Invite to supper at Hotel du Vin Yvonne Mosquito sponsors flollowing BPSO Proms £30.00 08/12/2012 declined Christmas lunch and drink offered. Small comemorative food consumed, Alcohol declined, Bob -

Birmingham Mental Health Recovery and Employment Service Prospectus - 2018

Birmingham Mental Health Recovery and Employment Service Prospectus - 2018 Hope - Control - Opportunity Birmingham Mental Health Recovery Service The Recovery Service offers recovery and wellbeing sessions to support mental, physical and emotional wellbeing in shared learning environments in the community. It will support people to identify and build on their own strengths and make sense of their experiences. This helps people take control, feel hopeful and become experts in their own wellbeing and recovery. Education and Shared Learning The Recovery Service provides an enablement approach to recovery, with an aim to empower people to live well through shared learning. As human beings we all experience our own personal recovery journeys and can benefit greatly from sharing and learning from each other in a safe and equal space. Co-production We aim for all courses to be developed and/or delivered in partnership with people who have lived experience (i.e. of mental health issues and/ or learning disabilities) or knowledge of caring for someone with these experiences. This model of shared learning allows for rich and diverse perspectives on living well with mental health or related issues. Eligibility This service shall be provided to service users who are: • Aged 18 years and above • Registered with a Birmingham GP for whom the commissioner is responsible for funding healthcare services • Residents of Birmingham registered with GP practices within Sandwell and West Birmingham CCG • Under the care of secondary mental health services or on the GP Serious Mental Illness register. Principles of Participation 1. Treat all service users and staff with compassion, dignity and respect and to not discriminate against or harass others at any time, respecting their rights, life choices, beliefs and opinions. -

Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Development Plan 2015 – 2031

Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Development Plan 2015 – 2031 Consultation Statement 1 Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Development Plan Consultation Statement This document is a record of the various stages and forms of consultation, statutory and non-statutory, which have been carried out during the making of the NDP, between 2011 and 2014. Contents Introduction, and summary of the three stages of consultation Page 3 Stage 1: initial consultation Page 5 Stage 2: consultation on draft proposals Page 22 Stage 3: pre-submission consultation Page 25 Appendix 1: Prince’s Foundation Workshop report Appendix 2: Reductions of the Stage 2 exhibition panels Appendix 3: Articles from The Heathan Appendix 4: Consultation Feedback Forms Appendix 5: Consultee List 2 1 Introduction 1.1 Balsall Heath, despite being among the UK’s 20% most deprived neighbourhoods, has a cohesive social structure, characterised by the existence of many social, religious, educational and business networks. These have been developed significantly over the past 30 years, largely by the efforts of local organisations such as Balsall Heath Forum and St Paul’s Community Trust. Many local people have been involved in constructive processes by which the social, environmental and economic conditions of Balsall Heath have been improved. People are used to being consulted, and this has been to the advantage of the NDP, which has used existing networks as a basis for the various stages of consultation. 1.2 Consultation processes have been consistent with the City Council’s policy Statement of Community Involvement (2008), which sets criteria and methods by which citizens are enabled and encouraged to be involved in planning issues. -

Harbury Road, Balsall Heath, Birmingham, West Midlands, B12 9NQ Asking Price £280,000

EPC C Harbury Road, Balsall Heath, Birmingham, West Midlands, B12 9NQ Asking Price £280,000 A modern four bedroom terraced property Located in Balsall Heath, close to Edgbaston cricket ground, Moseley Village and Cannon Hill Park. Public transport links into Birmingham City Centre and Selly Oak, (QE Hospital) are close by and local amenities are all within walking distance including a pharmacy. Perfect family home or investment opportunity as currently is let, great for someone looking for a property that has been recently built, and ready to move in to! It has two spacious reception rooms, a large kitchen with separate utility/laundry room and access into the garden. Upstairs over two floors are four double bedrooms, one with en suite shower room, one with en suite WC and a family shower room on the first floor. The property also benefits from a garage to the rear and a parking space, viewing is recommended to see the space available in this house. https://www.dixonsestateagents.co.uk Viewing arrangement by appointment 0121 449 6464 [email protected] Dixons, 95 Alcester Road, Moseley Interested parties should satisfy themselves, by inspection or otherwise as to the accuracy of the description given and any floor plans shown in these property details. All measurements, distances and areas listed are approximate. Fixtures, fittings and other items are NOT included unless specified in these details. Please note that any services, heating systems, or appliances have not been tested and no warranty can be given as to their working order. A member of Countrywide plc. Countrywide Estate Agents, trading as Dixons, registered office: Countrywide House, 88-103 Caldecotte Lake Drive, Caldecotte, Milton Keynes, MK7 8JT. -

Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Development Plan

Appendix 4 BALSALL HEATH NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN Basic Conditions Statement The accompanying draft Plan is submitted by a qualifying body The Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Development Plan (NDP) is submitted by the Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Planning Forum, which is a neighbourhood forum that meets the requirements of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended by the Localism Act) and has been designated as such by the local planning authority. Written confirmation of the designation by Birmingham City Council is included as an appendix. What is being proposed is a neighbourhood development plan The proposals in this NDP relate to planning matters (the use and development of land) and has been prepared in accordance with the statutory requirements and processes set out in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended by the Localism Act 2011) and the Neighbourhood Planning Regulations 2012. The proposed neighbourhood plan states the period for which it is to have effect It is confirmed that the plan specifies a time period for which it will be in force, namely 2014 to 2031, the latter being the time horizon for the draft Birmingham Development Plan (Local Plan/Core Strategy). The policies do not relate to excluded development The neighbourhood plan proposal does not deal with nationally significant infrastructure or any other matters set out in Section 61K of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. The proposed neighbourhood plan does not relate to more than one neighbourhood area and there are no other neighbourhood development plans in place within the neighbourhood area. The neighbourhood plan proposal relates to the Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Area – as approved by Birmingham City Council – and to no other area. -

4506 18 Draft Attachment 01.Pdf

West Midlands Police Freedom of Information POLICE STATIONS & BEAT OFFICES CLOSED SINCE APRIL 2010 DATE CURRENT CLOSED PROPERTY ADDRESS STATUS 20/05/2010 BORDESLEY GREEN POLICE STATION 280-282 Bordesley Green, Birmingham B9 5NA SOLD 20/5/10 27/07/2010 NORTHGATE BO 32 Northgate, Cradley Heath B64 6AU AGREEMENT TERMINATED 01/08/2010 BRAMFORD PRIMARY SCHOOL BO Park Road, Woodsetton, Dudley DY1 4JH AGREEMENT TERMINATED ST THOMAS'S COMMUNITY NETWORK 01/08/2010 Beechwood Road, Dudley DY2 7QA AGREEMENT TERMINATED BO 22/09/2010 WALKER ROAD BO 115 Walker Road, Blakenall, Walsall WS3 1DB AGREEMENT TERMINATED 23/09/2010 GREENFIELD CRESCENT BO 10 Greenfield Crescent, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 3AU AGREEMENT TERMINATED 26/10/2010 EVERDON ROAD BO 40 Everdon Road, Coventry CV6 4EF AGREEMENT TERMINATED 08/11/2010 MERRY HILL BO Unit U56B Upper Mall Phase 5, Merry Hill Centre, Dudley DY5 1QX AGREEMENT TERMINATED 03/02/2011 COURTAULDS BO 256 Foleshill Road, Great Heath, Coventry CV6 5AB AGREEMENT TERMINATED 25/02/2011 ASTON FIRE STATION NURSERY BO The Nursery Building, Ettington Road, Aston, Birmingham B6 6ED AGREEMENT TERMINATED 28/02/2011 BLANDFORD ROAD BO 125 Blandford Road, Quinton, Birmingham B32 2LT AGREEMENT TERMINATED 05/04/2011 LOZELLS ROAD BO 173A Lozells Road, Lozells, Birmingham B19 1RN AGREEMENT TERMINATED 30/06/2011 LANGLEY BO Albright & Wilson, Station Road, Langley, Oldbury B68 0NN AGREEMENT TERMINATED BILSTON POLICE STATION 10/08/2011 15 Mount Pleasant, Bilston WV14 7LJ SOLD 10/8/11 (old) HOLLYHEDGE HOUSE & MEWS 05/09/2011 2 Hollyhedge Road, -

Warding Arrangements for Legend Ladywood Ward

Newtown Warding Arrangements for Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Ward Legend Nechells Authority boundary Final recommendation North Edgbaston Ladywood Bordesley & Highgate Edgbaston 0 0.1 0.2 0.4 Balsall Heath West Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Bournville & Cotteridge Allens Cross Warding Arrangements for Longbridge & West Heath Ward Legend Frankley Great Park Northfield Authority boundary King's Norton North Final recommendation Longbridge & West Heath King's Norton South Rubery & Rednal 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Warding Arrangements for Lozells Ward Birchfield Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Aston Handsworth Lozells Soho & Jewellery Quarter Newtown 0 0.05 0.1 0.2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Tyseley & Hay Mills Warding Balsall Heath West Arrangements for Moseley Ward Edgbaston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Sparkhill Moseley Bournbrook & Selly Park Hall Green North Brandwood & King's Heath Stirchley Billesley 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Hall Green South Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Perry Barr Stockland Green Warding Pype Hayes Arrangements for Gravelly Hill Nechells Ward Aston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Bromford & Hodge Hill Lozells Ward End Nechells Newtown Alum Rock Glebe Farm & Tile Cross Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Heartlands Bordesley & Highgate 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Bordesley Green Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Handsworth Aston Warding Lozells Arrangements for Newtown Ward Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Newtown Nechells Soho & Jewellery Quarter 0 0.075 0.15 0.3 Ladywood Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database Ladywood right 2016. -

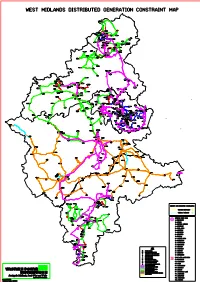

West Midlands Constraint Map-Default

WEST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP CONGLETON LEEK KNYPERSLEY PDX/ GOLDENHILL PKZ BANK WHITFIELD TALKE KIDSGROVE B.R. 132/25KV POP S/STN CHEDDLETON ENDON 15 YS BURSLEM CAULDON 13 CEMENT STAUNCH CELLARHEAD STANDBY F11 CAULDON NEWCASTLE FROGHALL TQ TR SCOT HAY STAGEFIELDS 132/ STAGEFIELDS MONEYSTONE QUARRY 33KV PV FARM PAE/ PPX/ PZE PXW KINGSLEY BRITISH INDUSTRIAL HEYWOOD SAND GRANGE HOLT POZ FARM BOOTHEN PDY/ PKY 14 9+10 STOKE CHEADLE C H P FORSBROOK PMZ PUW LONGTON SIMPLEX HILL PPW TEAN CHORLTON BEARSTONE P.S LOWER PTX NEWTON SOLAR FARM MEAFORD PCY 33KV C 132/ PPZ PDW PIW BARLASTON HOOKGATE PSX POY PEX PSX COTES HEATH PNZ MARKET DRAYTON PEZ ECCLESHALL PRIMARY HINSTOCK HIGH OFFLEY STAFFORD STAFFORD B.R. XT XT/ PFZ STAFFORD SOUTH GNOSALL PH NEWPORT BATTLEFIELD ERF GEN RUGELEY RUGELEY TOWN RUGELEY SWITCHING SITE HARLESCOTT SUNDORNE SOLAR FARM SPRING HORTONWOOD PDZ/ GARDENS PLX 1 TA DONNINGTON TB XBA SHERIFFHALES XU SHREWSBURY DOTHILL SANKEY SOLAR FARM ROWTON ROUSHILL TN TM 6 WEIR HILL LEATON TX WROCKWARDINE TV SOLAR LICHFIELD FARM SNEDSHILL HAYFORD KETLEY 5 SOLAR FARM CANNOCK BAYSTON PCD HILL BURNTWOOD FOUR ASHES PYD PAW FOUR ASHES E F W SHIFNAL BERRINGTON CONDOVER TU TS SOLAR FARM MADELEY MALEHURST ALBRIGHTON BUSHBURY D HALESFIELD BUSHBURY F1 IRONBRIDGE 11 PBX+PGW B-C 132/ PKE PITCHFORD SOLAR FARM I54 PUX/ YYD BUSINESS PARK PAN PBA BROSELEY LICHFIELD RD 18 GOODYEARS 132kV CABLE SEALING END COMPOUND 132kV/11kV WALSALL 9 S/STN RUSHALL PATTINGHAM WEDNESFIELD WILLENHALL PMX/ BR PKE PRY PRIESTWESTON LEEBOTWOOD WOLVERHAMPTON XW -

The VLI Is a Composite Index Based on a Range Of

OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership URN Date Issued CSP-SA-02 v3 11/02/2019 Customer/Issued To: Head of Community Safety, Birmingham Birmi ngham Community Safety Partnership Strategic Assessment 2019 The profile is produced and owned by West Midlands Police, and shared with our partners under statutory provisions to effectively prevent crime and disorder. The document is protectively marked at OFFICIAL but can be subject of disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 or Criminal Procedures and Investigations Act 1996. There should be no unauthorised disclosure of this document outside of an agreed readership without reference to the author or the Director of Intelligence for WMP. Crown copyright © and database rights (2019) Ordnance Survey West Midlands Police licence number 100022494 2019. Reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co. Ltd. © Crown Copyright 2019. All rights reserved. Licence number 100017302. 1 Page OFFICIAL OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership Contents Key Findings .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Reducing -

Food Banks / Clothes Banks

Food Banks / Clothes Banks Trussell Trust (Red Vouchers - If you do not know where to go to obtain a red Trussell Trust food voucher please contact either of the following telephone money / debt advice services. Citizens Advice Bureau 03444 771010. or. Birmingham Settlement Free Money Advice 0121 250 0765.) Voucher required Address Phone / E-mail Opening Central Foodbank 0121 236 2997 Fri 10am – 1.30pm Birmingham City Church Parade [email protected] B1 3QQ (parking B1 2RQ – please ensure you enter your vehicle registration on site before you leave the building to avoid a parking fine). Erdington Foodbank Six 07474 683927 Thurs 12.00 – 14.00 Ways Baptist Church Wood End Rd, Erdington [email protected] Birmingham B24 8AD George Road Baptist 07474 683927 Tues 12.00 – 14.00 Church George Road Erdington B23 7RZ [email protected] New Life Wesleyan 0121 507 0734 Thurs 13.00 – 15.00 Church Holyhead Rd, [email protected] Handsworth, Birmingham B21 0LA Sparkhill Foodbank 0121 708 1398 Thu 11.00 – 13.00 Balsall Heath Satellite [email protected] Balsall Heath Church Centre 100 Mary Street Balsall Heath Birmingham B12 9JU 1 Great Barr Foodbank St 0121 357 5399 Tues 12.00 – 14.00 Bernard's Church [email protected] Fri 12.00 – 14.00 Broome Ave, Birmingham B43 5AL Aston & Nechells 0121 359 0801 Mon 12 – 14.30 Foodbank St Matthews [email protected] Church 63 Wardlow Rd, Birmingham B7 4JH Aston & Nechells 0121 359 0801 Fri 12.30 – 14.30 Foodbank The Salvation Army Centre Gladstone [email protected] Street Aston Birmingham B6 7NY Non-Trussell Trust (No red voucher required) Address Phone / E-mail / Web-site Opening Birmingham City 0121 766 6603 (option 2) Mon – Fri 10am – Mission 2pm to speak to Puts you through to Wes – if someone is really in need, Wes The Clock Tower Wes will see about putting a food parcel together and deliver. -

Central Print and Bindery 10–12 Castle Road Birmingham Kings Norton Driving Maps B30 3ES Edgbaston Park

Kings Norton Business Centre Central Print and Bindery 10–12 Castle Road Birmingham Kings Norton driving maps B30 3ES Edgbaston Park Cotteridge University A38 A441 Canon Hill University of Park A4040 Birmingham WATFORD ROAD BRISTOL ROAD A441 PERSHORE ROAD A4040 Bournebrook A38 Selly Oak Selly Park Selly Oak Park Selly Oak A441 B4121 PERSHORE ROAD PERSHORE Selly Park MIDDLETON HALL ROAD OAK TREE LANE Selly Oak Hospital A441 Muntz Park Stirchley University of Kings Norton Castle Road Birmingham A4040 Bournville BRISTOL ROAD Station Road A38 LINDEN ROAD Dukes Road Cadbury Sovereign Road World Bournville Sovereign Road Park Bournville A441 Cotteridge ROAD PERSHORE Camp Lane Woodlands Park Park A4040 Melchett Road Dukes Road Cotteridge WATFORD ROAD Cotteridge Sovereign Road A4040 PERSHORE ROAD A441 WATFORD ROAD Prince Road MIDDLETON HALL ROAD B4121 B4121 Prince Road A441 A441 Melchett Road Kings Norton PERSHORE ROAD Kings Norton walking map A441 B4121 A441 PERSHORE ROAD PERSHORE Walking directions from Kings Norton station: MIDDLETON HALL ROAD Turn left out of the station and turn left again towards the Pershore Road. Turn left and make your way to the Crossing pedestrian crossing (approx 90 metres). Press the button and wait for green man before crossing over the road. Kings Norton Castle Road Turn right and walk down the road (approx 90 metres) until you see a walkway on your left. At the end of the walkway, Station Road take care to cross Sovereign Road and enter the car park Dukes Road entrance directly opposite (the entrance before Castle Sovereign Road Sovereign Road Road). We are the second large building on the left with a large black University of Birmingham sign above the reception entrance. -

Homes in Birmingham Soar 58% in a Decade

Classification: Public @HalifaxBankNews FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Not a Brum deal: homes in Birmingham soar 58% in a decade The average house price in Birmingham increased 58% since 2009 First-time buyers face costs of more than £32,000 to get on the ladder Halifax will host a series of first-time buyer events in Birmingham, demystifying the process of buying a home The average house price in Birmingham increased 14% faster over the last decade than the rest of the West Midlands, new research from Halifax can reveal. With a strong history of supporting home buyers and movers in Birmingham, Halifax has used its own data to look at how the market has developed over the past 10 years. House price landscape The average house price in the city currently sits at £219,355, an increase of 58% since 2009. In the same period, the average price of a house in the West Midlands has increased by 44%, and 48% across the UK. The average home for a first-time buyer costs £181,880 The average home for a homemover costs £285,664 The most expensive street in a Birmingham postcode is Rising Lane in Solihull, where the average house price is £1,908,000 Ladywood Road and Bracebridge Road, both in Sutton Coldfield, have an average house price in excess of £1.5m NHBC data shows over 13,800 new homes were built in the West Midlands in 2018. Mortgages Mortgage payments in Birmingham take up nearly a third (31%) of disposable earnings (Q4 2018) Mortgage freedom day, the day in which a homeowner could have paid off their mortgage for the year if all their income went to it, was the 22nd April 2019.