Making Ends Meet in Birmingham: Assessing the Impact of the Living Wage and Welfare Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calling Curious People in Bartley Green, Edgbaston, Harborne, North Edgbaston and Quinton

PRESS RELEASE NOVEMBER 24 2020 CALLING CURIOUS PEOPLE IN BARTLEY GREEN, EDGBASTON, HARBORNE, NORTH EDGBASTON AND QUINTON We at Artscoop (a network of local artists dedicated to arts with social purposes) are tickled pink to announce that we’ve got funding from Birmingham City Council to find out how ‘home art’ made by people living in SW Birmingham could feature in the Culture Programme of the 2022 Birmingham Commonwealth Games. By ‘home art’, we mean all those joyfully creative things that people make or do for themselves, their friends, families or work mates. Think whacky signs or banners, decorated gardens, inventions made in sheds, NHS rainbows, knitted oddities, floral shrines at accident spots, fancy dress, or ingenious scarecrows, There are hundreds of other unpredictable ways people celebrate who they are, where they live or work, and what they believe in…..or they just do it for fun. Home art definitely isn’t part of the ‘art world’: galleries and other arts institutions usually dismiss it, and it’s ignored by so-called experts. No matter, we’re asking people themselves to help us discover good examples in SW Birmingham. Between now and the end of January, send us photographs of what you think is home art and we’ll pay you for the ones we select to go in our on-line gallery. And that’s only the start – before Easter, we’ll be asking people how they think we can put on a show for 2022. If this interests you as a way of showing the world that Birmingham people are creative in their own special ways, get in touch at [email protected]. -

Evaluation of the Sheffield System for Identifying Children at Risk from Unexpected Death in Infancy

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.53.8.649 on 1 August 1978. Downloaded from Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1978, 53, 649-652 Evaluation of the Sheffield system for identifying children at risk from unexpected death in infancy Results from Birmingham and Newcastle upon Tyne J. R. OAKLEY, C. J. TAVARE, AND A. N. STANTON From the DHSS Multicentre Postneonatal Study, University of Sheffield SUMMARY The 'at birth' system which is used in Sheffield to identify children likely to die un- expectedly in infancy, was tested retrospectively in Birmingham (83 cases) and in Newcastle upon Tyne (56 cases). The discrimination between cases and age-matched controls was poor in both cities. Analysis of the 8 factors used in the system showed that only 2 maintained significant case/ control differences in Birmingham and Newcastle. Further investigation showed that other factors from maternity records showed significant case/control differences in these cities. Although the system used in Sheffield would not be of use in a prospective prevention programme in either Newcastle or Birmingham, the possibility of evolving an 'at risk' system which might apply more widely is discussed. copyright. A system for identifying, early in life, children likely as have those who presented to hospital in a mori- to die unexpectedly in infancy has been evolved in bund state. Sheffield (Carpenter et al., 1977). Numerical weight- A living control was chosen for each case by ings of 8 factors taken from obstetric and perinatal taking the next live birth surviving from the same records allows nearly 60% of subsequent deaths to maternity hospital as the index, whose parents were be identified in approximately 15 % ofthe population, living within the same city boundaries as the index but the system may not be valid outside Sheffield. -

Birmingham Mental Health Recovery and Employment Service Prospectus - 2018

Birmingham Mental Health Recovery and Employment Service Prospectus - 2018 Hope - Control - Opportunity Birmingham Mental Health Recovery Service The Recovery Service offers recovery and wellbeing sessions to support mental, physical and emotional wellbeing in shared learning environments in the community. It will support people to identify and build on their own strengths and make sense of their experiences. This helps people take control, feel hopeful and become experts in their own wellbeing and recovery. Education and Shared Learning The Recovery Service provides an enablement approach to recovery, with an aim to empower people to live well through shared learning. As human beings we all experience our own personal recovery journeys and can benefit greatly from sharing and learning from each other in a safe and equal space. Co-production We aim for all courses to be developed and/or delivered in partnership with people who have lived experience (i.e. of mental health issues and/ or learning disabilities) or knowledge of caring for someone with these experiences. This model of shared learning allows for rich and diverse perspectives on living well with mental health or related issues. Eligibility This service shall be provided to service users who are: • Aged 18 years and above • Registered with a Birmingham GP for whom the commissioner is responsible for funding healthcare services • Residents of Birmingham registered with GP practices within Sandwell and West Birmingham CCG • Under the care of secondary mental health services or on the GP Serious Mental Illness register. Principles of Participation 1. Treat all service users and staff with compassion, dignity and respect and to not discriminate against or harass others at any time, respecting their rights, life choices, beliefs and opinions. -

Cardiff Leeds London Manchester Newcastle Upon Tyne K24/40C

K24/40c DPP Planning Barnett House 53 Fountain Street Manchester M2 2AN t 0161 247 8555 info@dppukltd www.dppukltd.com Mr Michael J Hetherington C/O Tina Kelly, Programme Officer C/O Development Management Telford & Wrekin Council PO Box 457 Wellington Civic Offices Telford TF2 2FH ViaViaVia emailemailemail onlyonlyonly Ref: 2341ma/L006m Date: 6 Mar 2017 Dear Sir Telford & Wrekin Local Plan 201120112011-2011---20312031 Examination Response to Council Paper K24/40a on behalf of Tesni Properties Ltd (ID 929966) This letter provides comments on the above Paper submitted by the Council in response to your question what methodology it used at the Stage Three ‘Strategic Fit’ site selection to move from 314 potential housing sites to its preferred 24 sites / 17 allocations. Paper K24/40a and Appendices 1 and 2 provides new evidence in the form of the ‘planning assessment’ on the ten Strategic Fit criteria and scoring for 99 of the 314 assessed sites. The Paper cross-references Papers/Evidence in J8/TWC and B2b as demonstration of its full detailed methodology. It is noted that within these documents other parts of the evidence base are further referenced, of most significance the Integrated (Sustainability) Appraisal Report 2015 (D4b) and its Update 2016 (A3a). Summary and conclusions The following points are expanded upon below, drawn from a review of the Paper and the implications for the preparation of the Plan. 1.EvEvEvidence Evidence of prepre----determinationdetermination in the ‘methodology’‘methodology’. By far the most serious and significant facet of the evidence is how it shows potential for pre-determination of the selected sites, and that the Stage Three exercise was not conducted transparently or to a consistent methodology. -

The List of Pharmacies Registered to Sell Ppcs on Our Behalf Is Sorted Alphabetically in Postcode Order

The list of pharmacies registered to sell PPCs on our behalf is sorted alphabetically in postcode order. 0 NAME PREMISES ADDRESS 1 PREMISES ADDRESS 2 PREMISES ADDRESS 3 PREMISES ADDRESS 4 LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, EVERARD CLOSE ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 2QU BOOTS UK LIMITED 9 ST PETERS STREET ST.ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3DH FREEMAN GRIEVES LTD 111-113 ST PETERS STREET ST.ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3ET LLOYDS PHARMACY PARKBURY HOUSE ST PETER ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3HD IMED PHARMACY 67 HATFIELD ROAD ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 4JE LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, BARNET ROAD LONDON COLNEY ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL2 1AB LLOYDS PHARMACY 17 RUSSELL AVENUE ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL3 5ES CROWN PHAMRACY 65 HIGH STREET REDBOURN ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL3 7LW MANOR PHARMACY (WHEATHAMPSTEAD) LTD 2 HIGH STREET WHEATHAMPSTEAD HERTFORDSHIRE AL4 8AA BOOTS UK LIMITED 23-25 HIGH STREET HARPENDEN HERTFORDSHIRE AL5 2RU LLOYDS PHARMACY 40 HIGH STREET WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL6 9EQ LLOYDS PHARMACY 84 HALDENS WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 1DD BOOTS UK LIMITED 65 MOORS WALK WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 2BQ BOOTS UK LIMITED 31 COLE GREEN LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3PP PEARTREE PHARMACY 110 PEARTREE LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3UJ BOOTS UK LIMITED 126 PEARTREE LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3XY BOOTS UK LIMITED 31 THE HOWARD CENTRE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL8 6HA LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, CHURCH ROAD WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL8 6SA LLOYDS PHARMACY 9 SHOPLANDS WELWYN GARDEN -

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet Member for Education Skills and Culture, Jointly with the Director of Education &

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet Member for Education Skills and Culture, jointly with the Director of Education & Skills Date: 14 June 2019 Subject: PROPOSAL TO TRANSFER OSCOTT MANOR SCHOOL TO A NEW SITE Report of: Interim Assistant Director for Education and Early Years Relevant Cabinet Councillor Jayne Francis, Education Skills and Culture Member: Relevant O &S Chair(s): Councillor Kath Scott, Education & Children’s Social Care Report author: Jaswinder Didially Head of Service, Education Infrastructure; Telephone No: 0121 303 8847 E-mail address: [email protected] Are specific wards affected? ☒ Yes ☐ No – All wards affected If yes, name(s) of ward(s): Oscott and Stockland Green are the wards most likely to be affected but pupils travel from across the city to access this specialist provision. Is this a key decision? ☐ Yes ☒ No If relevant, add Forward Plan Reference: Is the decision eligible for call-in? ☒ Yes ☐ No Does the report contain confidential or exempt information? ☐ Yes ☒ No If relevant, provide exempt information paragraph number or reason if confidential : 1 Executive Summary 1.1 To seek the determination of a statutory proposal: • To Transfer Oscott Manor School from Old Oscott Hill, Birmingham B44 9SP to Reservoir Road, Erdington, Birmingham B23 6DE with effect from 1 November 2021. Page 1 of 7 2 Recommendations That the Cabinet Member for Education, Skills and Culture jointly with the Director for Education & Skills; 2.1 Approve, having taken into account the statutory guidance, the statutory proposal to transfer Oscott Manor School to a new site. 3 Background 3.1 Oscott Manor School is a community special school situated in the Oscott ward in the Perry Barr district of the City. -

Historical and Contemporary Archaeologies of Social Housing: Changing Experiences of the Modern and New, 1870 to Present

Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Emma Dwyer School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester 2014 Thesis abstract: Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Emma Dwyer This thesis has used building recording techniques, documentary research and oral history testimonies to explore how concepts of the modern and new between the 1870s and 1930s shaped the urban built environment, through the study of a particular kind of infrastructure that was developed to meet the needs of expanding cities at this time – social (or municipal) housing – and how social housing was perceived and experienced as a new kind of built environment, by planners, architects, local government and residents. This thesis also addressed how the concepts and priorities of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and the decisions made by those in authority regarding the form of social housing, continue to shape the urban built environment and impact on the lived experience of social housing today. In order to address this, two research questions were devised: How can changing attitudes and responses to the nature of modern life between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries be seen in the built environment, specifically in the form and use of social housing? Can contradictions between these earlier notions of the modern and new, and our own be seen in the responses of official authority and residents to the built environment? The research questions were applied to three case study areas, three housing estates constructed between 1910 and 1932 in Birmingham, London and Liverpool. -

Warding Arrangements for Legend Ladywood Ward

Newtown Warding Arrangements for Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Ward Legend Nechells Authority boundary Final recommendation North Edgbaston Ladywood Bordesley & Highgate Edgbaston 0 0.1 0.2 0.4 Balsall Heath West Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Bournville & Cotteridge Allens Cross Warding Arrangements for Longbridge & West Heath Ward Legend Frankley Great Park Northfield Authority boundary King's Norton North Final recommendation Longbridge & West Heath King's Norton South Rubery & Rednal 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Warding Arrangements for Lozells Ward Birchfield Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Aston Handsworth Lozells Soho & Jewellery Quarter Newtown 0 0.05 0.1 0.2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Tyseley & Hay Mills Warding Balsall Heath West Arrangements for Moseley Ward Edgbaston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Sparkhill Moseley Bournbrook & Selly Park Hall Green North Brandwood & King's Heath Stirchley Billesley 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Hall Green South Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Perry Barr Stockland Green Warding Pype Hayes Arrangements for Gravelly Hill Nechells Ward Aston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Bromford & Hodge Hill Lozells Ward End Nechells Newtown Alum Rock Glebe Farm & Tile Cross Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Heartlands Bordesley & Highgate 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Bordesley Green Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Handsworth Aston Warding Lozells Arrangements for Newtown Ward Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Newtown Nechells Soho & Jewellery Quarter 0 0.075 0.15 0.3 Ladywood Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database Ladywood right 2016. -

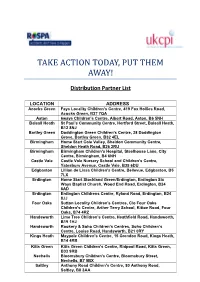

Take Action Today, Put Them Away!

TAKE ACTION TODAY, PUT THEM AWAY! Distribution Partner List LOCATION ADDRESS Acocks Green Fays Locality Children’s Centre, 419 Fox Hollies Road, Acocks Green, B27 7QA Aston 6ways Children’s Centre, Albert Road, Aston, B6 5NH Balsall Heath St Paul’s Community Centre, Hertford Street, Balsall Heath, B12 8NJ Bartley Green Doddington Green Children's Centre, 28 Doddington Grove, Bartley Green, B32 4EL Birmingham Home Start Cole Valley, Sheldon Community Centre, Sheldon Heath Road, B26 2RU Birmingham Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Steelhouse Lane, City Centre, Birmingham, B4 6NH Castle Vale Castle Vale Nursery School and Children’s Centre, Yatesbury Avenue, Castle Vale, B35 6DU Edgbaston Lillian de Lissa Children's Centre, Bellevue, Edgbaston, B5 7LX Erdington Home Start Stockland Green/Erdington, Erdington Six Ways Baptist Church, Wood End Road, Erdington, B24 8AD Erdington Erdington Childrens Centre, Ryland Road, Erdington, B24 8JJ Four Oaks Sutton Locality Children's Centres, C/o Four Oaks Children’s Centre, Arther Terry School, Kittoe Road, Four Oaks, B74 4RZ Handsworth Lime Tree Children’s Centre, Heathfield Road, Handsworth, B19 1HJ Handsworth Rookery & Soho Children’s Centres, Soho Children’s Centre, Louise Road, Handsworth, B21 0RY Kings Heath Maypole Children’s Centre, 15 Grendon Road, Kings Heath, B14 4RB Kitts Green Kitts Green Children’s Centre, Ridpool Road, Kitts Green, B33 9RB Nechells Bloomsbury Children's Centre, Bloomsbury Street, Nechells, B7 5BX Saltley Anthony Road Children’s Centre, 80 Anthony Road, Saltley, B8 3AA Small Heath Waverley Children’s Centre, 311 Yardley Green Road, Small Heath, B9 5QA Solihull Solihull A&E, 1st Floor, 3 The Green, Stratford road, Shirley B90 4LA Stechford Bordesley Green East Nursery & Children's Centre, 358 Bordesley Green East, Stechford, B33 8QB Sutton Home-Start Sutton Coldfield, United Reformed Church, B27 Coldfield 36A West Heath Longbridge Locality Children's Centres, 49 Merrishaw Road, West Heath, B31 3SL Wolverhampton Bushbury Triangle Children's Centre, Stanley Road, Bushbury, Wolverhampton, WV10 9EL . -

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet 14Th May 2019

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet 14th May 2019 Subject: Houses in Multiple Occupation Article 4 Direction Report of: Director, Inclusive Growth Relevant Cabinet Councillor Ian Ward, Leader of the Council Members: Councillor Sharon Thompson, Cabinet Member for Homes and Neighbourhoods Councillor John Cotton, Cabinet Member for Social Inclusion, Community Safety and Equalities Relevant O &S Chair(s): Councillor Penny Holbrook, Housing & Neighbourhoods Report author: Uyen-Phan Han, Planning Policy Manager, Telephone No: 0121 303 2765 Email Address: [email protected] Are specific wards affected? ☒ Yes ☐ No If yes, name(s) of ward(s): All wards Is this a key decision? ☒ Yes ☐ No If relevant, add Forward Plan Reference: 006417/2019 Is the decision eligible for call-in? ☒ Yes ☐ No Does the report contain confidential or exempt information? ☐ Yes ☒ No 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Cabinet approval is sought to authorise the making of a city-wide direction under Article 4 of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 2015. This will remove permitted development rights for the change of use of dwelling houses (C3 Use Class) to houses in multiple occupation (C4 Use Class) that can accommodate up to 6 people. 1.2 Cabinet approval is also sought to authorise the cancellation of the Selly Oak, Harborne and Edgbaston Article 4 Direction made under Article 4(1) of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 1995. This is to avoid duplication as the city-wide Article 4 Direction will cover these areas. Page 1 of 8 2 Recommendations 2.1 That Cabinet authorises the Director, Inclusive Growth to prepare a non- immediate Article 4 direction which will be applied to the City Council’s administrative area to remove permitted development rights for the change of use of dwelling houses (C3 use) to small houses in multiple occupation (C4 use). -

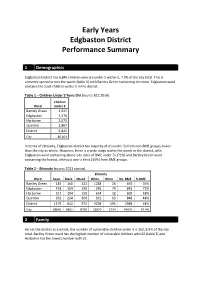

Early Years Edgbaston District Performance Summary

Early Years Edgbaston District Performance Summary 1 Demographics Edgbaston District has 6,845 children who are under 5 within it, 7.9% of the city total. This is unevenly spread across the wards (table 1) with Bartley Green containing the most. Edgbaston ward contains the least children under 5 in the district. Table 1 – Children Under 5 Years Old (source BCC 2016) Children Ward Under 5 Bartley Green 1,927 Edgbaston 1,376 Harborne 1,675 Quinton 1,867 District 6,845 City 86,601 In terms of ethnicity, Edgbaston district has majority of it’s under 5s from non-BME groups, lower than the city as whole. However, there is a wide range within the wards in the district, with Edgbaston ward containing above city rates of BME under 5s (71%) and Bartley Green ward containing the lowest, with just over a third (35%) from BME groups. Table 2 – Ethnicity (source 2011 census) Ethnicity Ward Asian Black Mixed White Other No. BME % BME Bartley Green 183 160 323 1288 26 692 35% Edgbaston 418 154 199 345 74 845 71% Harborne 317 104 150 654 32 603 48% Quinton 261 224 300 921 63 848 48% District 1179 642 972 3208 195 2988 48% City 28846 8661 8790 32870 2734 49031 59.9% 2 Family Across the district as a whole, the number of vulnerable children under 5 is 162, 8.9% of the city total. Bartley Green ward has the highest number of vulnerable children with 62 (table 3) and Harborne has the lowest number with 21. In terms of vulnerable children Edgbaston district has above city rates for vulnerable children who are under 5 years old. -

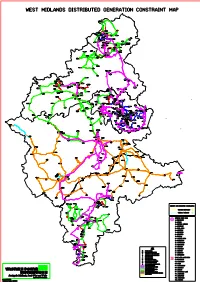

West Midlands Constraint Map-Default

WEST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP CONGLETON LEEK KNYPERSLEY PDX/ GOLDENHILL PKZ BANK WHITFIELD TALKE KIDSGROVE B.R. 132/25KV POP S/STN CHEDDLETON ENDON 15 YS BURSLEM CAULDON 13 CEMENT STAUNCH CELLARHEAD STANDBY F11 CAULDON NEWCASTLE FROGHALL TQ TR SCOT HAY STAGEFIELDS 132/ STAGEFIELDS MONEYSTONE QUARRY 33KV PV FARM PAE/ PPX/ PZE PXW KINGSLEY BRITISH INDUSTRIAL HEYWOOD SAND GRANGE HOLT POZ FARM BOOTHEN PDY/ PKY 14 9+10 STOKE CHEADLE C H P FORSBROOK PMZ PUW LONGTON SIMPLEX HILL PPW TEAN CHORLTON BEARSTONE P.S LOWER PTX NEWTON SOLAR FARM MEAFORD PCY 33KV C 132/ PPZ PDW PIW BARLASTON HOOKGATE PSX POY PEX PSX COTES HEATH PNZ MARKET DRAYTON PEZ ECCLESHALL PRIMARY HINSTOCK HIGH OFFLEY STAFFORD STAFFORD B.R. XT XT/ PFZ STAFFORD SOUTH GNOSALL PH NEWPORT BATTLEFIELD ERF GEN RUGELEY RUGELEY TOWN RUGELEY SWITCHING SITE HARLESCOTT SUNDORNE SOLAR FARM SPRING HORTONWOOD PDZ/ GARDENS PLX 1 TA DONNINGTON TB XBA SHERIFFHALES XU SHREWSBURY DOTHILL SANKEY SOLAR FARM ROWTON ROUSHILL TN TM 6 WEIR HILL LEATON TX WROCKWARDINE TV SOLAR LICHFIELD FARM SNEDSHILL HAYFORD KETLEY 5 SOLAR FARM CANNOCK BAYSTON PCD HILL BURNTWOOD FOUR ASHES PYD PAW FOUR ASHES E F W SHIFNAL BERRINGTON CONDOVER TU TS SOLAR FARM MADELEY MALEHURST ALBRIGHTON BUSHBURY D HALESFIELD BUSHBURY F1 IRONBRIDGE 11 PBX+PGW B-C 132/ PKE PITCHFORD SOLAR FARM I54 PUX/ YYD BUSINESS PARK PAN PBA BROSELEY LICHFIELD RD 18 GOODYEARS 132kV CABLE SEALING END COMPOUND 132kV/11kV WALSALL 9 S/STN RUSHALL PATTINGHAM WEDNESFIELD WILLENHALL PMX/ BR PKE PRY PRIESTWESTON LEEBOTWOOD WOLVERHAMPTON XW