D.A.R.U.G Project Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Community Protocols for Bankstown Area Multicultural Network

INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY PROTOCOLS FOR BAMN MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Practical protocols for working with the Indigenous Community of South West Sydney 1 Contents RESPECT, ACKNOWLEDGE, LISTEN Practical protocols for working with Indigenous communities in Western Sydney What are protocols? 1. Get To Know Your Indigenous Community Identity Diversity – Different rules for different community groups (there can sometimes be different groups within communities) 2. Consult Indigenous Reference Groups, Steering Committees and Boards 3. Get Permission The Local Community Elders Traditional Owners Ownership Copyright and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property 4. Communicate Language Koori Time Report back and stay in touch 5. Ethics and Morals Confidentiality Integrity and trust 6. Correct Procedures Respect What to call people Traditional Welcome or Welcome to Country Acknowledging Traditional Owners Paying People Indigenous involvement Cross Cultural Training 7. Indigenous Organisations and Western Sydney contacts Major Indigenous Organisations Local Aboriginal Land Councils Indigenous Corporations/Community Organisations Indigenous Council, Community and Arts workers 8. Keywords to Remember 9. Other Protocol Resource Documents 2 What Are Protocols? Protocols can be classified as a set of rules, regulations, processes, procedures, strategies, or guidelines. Protocols are simply the ways in which you work with people, and communicate and collaborate with them appropriately. They are a guide to assist you with ways in which you can work, communicate and collaborate with the Indigenous community of Western Sydney. A wealth of Indigenous protocols documentation already exists (see Section 9), but to date the practice of following them is not widespread. Protocols are also standards of behaviour, respect and knowledge that need to be adopted. You might even think of them as a code of manners to observe, rather than a set of rules to obey. -

Practical Protocols for Working with the Indigenous Community of Western Sydney

CCD_RAL_bk.qxd 15/7/03 3:04 PM Page 1 CCD_RAL_Final.qxd 15/7/03 3:06 PM Page 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was assisted by the Government of NSW through the and The Federal Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Researched and Written by This document is a project of the Angelina Hurley Indigenous Program of Indigenous Program Manager Community Cultural Development New Community Cultural Development NSW South Wales (CCDNSW) Draft Review and Copyright Section by © Community Cultural Development NSW Terri Janke Ltd, 2003 Principle Solicitor Terri Janke and Company Suite 8 54 Moore St. Design and Printing by Liverpool NSW 2170 MLC Powerhouse Design Studio PO Box 512 April 2003 Liverpool RC 1871 Ph: (02) 9821 2210 Cover Art Work Fax: (02) 9821 3460 ‘You Can’t Have Our Spirituality Without Web: www.ccdnsw.org Our Political Reality’ by Indigenous Artist Gordon Hookey Internal Art Work ‘Men’s Ceremony’ by Indigenous Artist Adam Hill CCD_RAL_Final.qxd 15/7/03 5:05 PM Page 2 Contents RESPECT, ACKNOWLEDGE, LISTEN: Practical protocols for working with the Indigenous Community of Western Sydney . .3 Who are Community Cultural Development New South Wales (CCDNSW)? What is ccd? . .3 What Are Protocols? . .3 1. Get To Know Your Indigenous Community . .4 Identity . .5 Diversity - Different Rules For Different Groups . .6 2. Consult . .6 Indigenous Reference Groups, Steering Committees and Boards . .7 3. Get Permission . .8 The Local Community . .8 Elders . .8 Traditional Owners . .8 Ownership . .9 Copyright And Indigenous Cultural And Intellectual Property . .9 4. Communicate . .10 Language . .10 Koori Time . -

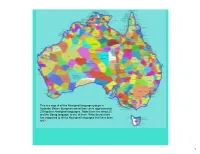

This Is a Map of All the Aboriginal Language Groups in Australia

This is a map of all the Aboriginal language groups in Australia. Before European arrival there were approximately 250 spoken Aboriginal languages. Today there are about 25, and the Darug language is one of them. What do you think has happened to all the Aboriginal languages that have been lost? 1 Do you speak my language? This lesson: Learning to speak some of the Darug language Aunty Val Aurisch Speaking at The Gully Culture Camp 2010 Picture soured 20 April 2011 from: http://www.livingcountry.com.au/gallery.cfm 2 Listen to me speak the Darug language Richard Green helps keep his language alive and strong by teaching it to students at Chifley College, Dunheved Campus and at Doonside Technical High School. Listen to Richard Green talk about his language in Darug (and English) by clicking on the picture of Richard. This will take you to to the William Dawes website where you can listen to an mp3 file. Richard Green Picture: Copyright 2009 The Hills Shire Council 3 Can you speak Darug language? Click the Darug name and drag it to the 'Word' column. Select the check button to find out how you went! Words sourced from Yarramundi Kids website on 20 April 2011: http://yarramundikids.tv/yarramundikids/howdoyousay.html 4 A shared historyA brief introduction to Lieutenant William Dawes Lieutenant William Dawes (1762-1836) was known as an officer of marines, scientist and administrator, yet it is his interest in studying the local Eora (Darug) people that tells the story of a shared history. Dawes developed a friendship with a young Darug girl who was about fifteen years old. -

Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal Ways of Being Into Teaching Practice in Australia

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2020 Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal ways of being into teaching practice in Australia Lisa Buxton The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Education Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Buxton, L. (2020). Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal ways of being into teaching practice in Australia (Doctor of Education). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/248 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal ways of being into teaching practice in Australia Lisa Maree Buxton MPhil, MA, GDip Secondary Ed, GDip Aboriginal Ed, BA. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Education School of Education Sydney Campus January, 2020 Acknowledgement of Country Protocols The protocol for introducing oneself to other Indigenous people is to provide information about one’s cultural location, so that connection can be made on political, cultural and social grounds and relations established. (Moreton-Robinson, 2000, pp. xv) I would like firstly to acknowledge with respect Country itself, as a knowledge holder, and the ancients and ancestors of the country in which this study was conducted, Gadigal, Bidjigal and Dharawal of Eora Country. -

Aboriginal Design Principles

WAGGA WAGGA SPECIAL ACTIVATION PRECINCT WIRADJURI COUNTRY ABORIGINAL DESIGN PRINCIPLES This document acknowledges the elders, past and present, of the Wiradjuri people as the traditional owners of Wagga Wagga and the lands knowledge. / Explorer Mitchell (1839) described “a beautiful plain; covered with shining verdure [lush green vegetation] and ornamented with trees… gave the country the appearance of an extensive park” Contents Document produced by Michael Hromek WSP Australia Pty Ltd. 01. Wiradjuri Country Descended from the Budawang tribe of the Yuin nation, Michael is currently working at WSP, doing a PhD in architecture People and Design and teaches it at the University of Technology Sydney in the Bachelor of Design in Architecture. [email protected] 02. Aboriginal Planning Principles Research by Sian Hromek (Yuin) Graphic design by Sandra Palmer, WSP 03. Project Site Application of Aboriginal Planning and Design Principles 04. Project Examples Examples of Indigenous planning and design applied to projects of similar scope 05. Indigenous participation strategy Engaging Community through co-design strategies Image above: Sennelier Watercolour - Light Yellow Ochre (254) Please note: In order to highlight the use of Aboriginal Design Principles, this document may contain examples from other Aboriginal Countries. 01 WIRADJURI COUNTRY - 1 - Indigenous specialist services When our Country is acknowledged and returned to us, Aboriginal design principles it completes our songline, makes us feel culturally proud, Indigenous led/ Indigenous people (designers, elders etc) and strengthens our identity and belonging. should be leading or co-leading the Indigenous elements in the design. Wurundjeri Elder, Annette Xiberras. Community involvement/ The local Indigenous community to be engaged in this process, can we use their patterns? Can they design patterns for the project? Appropriate use of Indigenous design/ All Indigenous Indigenous design statement design elements must be approved of by involved Indigenous people / community / elders. -

Working with Aboriginal People and Communities

Produced by Aboriginal Services Branch in consultation with the Aboriginal Reference Group NSW Department of Community Services 4-6 Cavill Avenue Ashfield NSW 2131 Phone (02) 9716 2222 February 2009 ISBN 1 74190 097 2 www.community.nsw.gov.au A number of NSW Department of As Aboriginal people are the Community Service (Community original inhabitants of NSW; and Services) regions as well as several as the NSW Government only has other government agencies have a specific charter of service to the created their own practice guides people of NSW, this document for working with Aboriginal people refers only to Aboriginal people. and communities. In developing References to Torres Strait Islander this practice resource, we have people will be specifically stated combined the best elements of where relevant. It is important existing practices to develop to remember that Aboriginal and a resource that provides a Torres Strait Islander cultures are consistent approach to working very different, with their own with Aboriginal people and unique histories, beliefs and values. communities.1 It is respectful to recognise their separate identities. Community The information and practice tips Services recognise that Torres contained in this document are Strait Islander people are among generalisations and do not reflect the First Nations of Australia the opinions of all Aboriginal and represent a part of our client people and communities in NSW. and staff base. The Department’s There may be exceptions to the Aboriginal programs and services information -

2007. Assessment of the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Values of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area

Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute’s Natural and Cultural Heritage Program Assessment of the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Values of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area A Report for the Department of Environment and Water Resources By Paul S.C. Taçon, Shaun Boree Hooper, Wayne Brennan, Graham King, Matthew Kelleher, Joan Domicelj, and John Merson 2007 © Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute & Griffith University Table of Contents Page 1. An Introduction to the Assessment Process. 3 2. The Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (GBMWHA) 5 3. The Landscape of Blue Mountains Rock Art. 11 4. Discussion and Significance of Newly Discovered Wollemi Sites 29 5. An Indigenous perspective on the GMBWHA Rock Art 33 6. Comparison of Rock Art in the Sydney Basin and the GBMWHA 37 7. Conclusions and Comparison of the GBMWHA to other regions 39 Appendix 1 Distribution of Aboriginal Heritage Sites within the GBMWHA 46 2 1. An Introduction to the Assessment Process This report is part of a larger series of reports in response to a proposal to place the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area on the National Heritage List. In the brief, Summaries of Indigenous heritage values for the Greater Blue Mountains Area nominated to the National Heritage List, it was required that the cultural heritage of the Greater Blue Mountains area be assessed in comparison to that of other regions as well as against each of the National Heritage List criteria (consultancy brief required output 4). More specifically, Section 324D of the Environment -

Aborigines in the Hills District the Cumberland Plain Aboriginal

Aborigines in the Hills District The Cumberland Plain Aboriginal people have been living in the Sydney region for at least 40,000 years.1 The people living in The Hills belonged to the Darug tribe of which there were a number of family groups or clans that were nomadic within a specific area. For example, the Burramattagal clan (burra - eels and fish, matta – place of fresh running water) occupied the Parramatta/North Rocks area of Hunts and Darling Mills Creeks; the Toongagal or Tuga clan (place of thick woods) lived in the Toongabbie Creek/Hawkesbury River catchment. These clans spoke the inland dialect of the Darug language.2 The Darug people were not confined only to The Hills area and spread out all over the Cumberland Plain. This area stretches from Windsor in the north to Picton in the south and into the inner west of Sydney. Most of Western Sydney was home to the Darug people and as such their traditions, culture and lifestyle is not unique to The Hills but represents Aborigines from a number of other local government areas as well. The Darug people of the Cumberland Plain usually camped within 100m of permanent water sources as a home base. There is evidence of camps further away than that however very few have been recorded as being further than 500m from water.3 Remains of both open camps and cave dwellings have been discovered in the Hills Shire, with charcoal drawings, shellfish middens, animal bones and stone flakes being discovered in caves. The rock dwellings found in the Darling Mills Creek area of West Pennant Hills date back almost 12,000 years.4 Culture and Diet Darug people travelled along the ridgelines (often the routes of present day roads) and followed creeks to sacred sites in the Hills District and elsewhere in Western Sydney for special ceremonies and gatherings. -

HSIE Assignment 3. Cultures Darug People of Sydney

HSIE Assignment 3. Cultures Darug People of Sydney. Rationale. The rationale of this Unit of Work is to have Stage 3 students achieve certain outcomes of the HSIE KLA. Those outcomes are concentrated in the Cultures strand of the syllabus but also in other strands. Specifically those outcomes are CCS3.1, CUS3.3, CUS3.4, ENS3.5 and ENS3.6. This unit of Work hopes to give students a thorough respect, appreciation and knowledge of the Darug people of Sydney and their culture at the time of the arrival of the First Fleet. It also wishes to place that time firmly in the context of change and continuity making reference to the present day Sydney. The culture, social systems and structures of mainly the Darugs, but also the First Fleet are presented and their interaction with the environment is a strong focus and perspective of the Unit of Work. The teaching and learning strategies are a strong mix of auditory, visual and written stimuli. The Unit of Work relies heavily on group work and role play. A series of background information is presented and the students are engaged by working together 'in role' to solve problems that the Darugs and British First Fleeters would have to face. After this engagement, historical information is supplied and the students asked to assess their group ideas with the realities of decisions made by the Darug and British. In this way students are engaged in a fun and expressive way, learning from eachother but also strongly understanding the material presented to them as it relates directly to their group role play. -

Social Context

Dreamtime Superhighway: an analysis of Sydney Basin rock art and prehistoric information exchange 3 SOCIAL conteXT While anthropology can help elucidate the complexity of cultural systems at particular points in time, archaeology can best document long-term processes of change (Layton 1992b:9) In the original thesis one chapter was dedicated to the ethnohistoric and early sources for the Sydney region and another to previous regional archaeological research. Since 1994, Valerie Attenbrow has published both her PhD thesis (1987, 2004) and the results of her Port Jackson Archaeological Project (Attenbrow 2002). More recent, extensive open area excavations on the Cumberland Plain done as cultural heritage management mitigations (e.g. JMcD CHM 2005a, 2005b, 2006) have also altered our understanding of the region’s prehistory. As Attenbrow’s Sydney’s Aboriginal Past (2002) deals extensively with ethnohistoric evidence from the First Fleet and early days of the colony the ethnohistoric and historic sources explored for this thesis have been condensed to provide the rudiments for the behavioral model developed for prehistoric Sydney rock art. The British First Fleet sailed through Sydney Heads on 26 January 1788. Within two years an epidemic of (probably) smallpox had reduced the local Aboriginal population significantly – in Farm Cove the group which was originally 35 people in size was reduced to just three people (Phillip 1791; Tench 1793; Collins 1798; Butlin 1983; Curson 1985; although see Campbell 2002). This epidemic immediately and irreparably changed the traditional social organisation of the region. The Aboriginal society around Port Jackson was not studied systematically, in the anthropological sense, by those who arrived on the First Fleet. -

Phillip and the Eora Governing Race Relations in the Colony of New South Wales

Phillip and the Eora Governing race relations in the colony of New South Wales Grace Karskens In the Botanic Gardens stands a grand monument to Arthur Phillip, the first governor of New South Wales. Erected 1897 for the Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, the elaborate fountain encapsulates late nineteenth century ideas about society and race. Phillip stands majestically at the top, while the Aboriginal people, depicted in bas relief panels, are right at the bottom. But this is not how Phillip acted towards Aboriginal people. In his own lifetime, he approached on the same ground, unarmed and open handed. He invited them into Sydney, built a house for them, shared meals with them at his own table.1 What was Governor Arthur Phillip's relationship with the Eora, and other Aboriginal people of the Sydney region?2 Historians and anthropologists have been exploring this question for some decades now. It is, of course, a loaded question. Phillip's policies, actions and responses have tended to be seen as a proxy for the Europeans in Australia as whole, just as his friend, the Wangal warrior Woolarawarre Bennelong, has for so long personified the fate of Aboriginal people since 1788.3 The relationship between Phillip and Bennelong has been read as representing not only settler-Aboriginal relations in those first four years but as the template for the following two centuries of cross-cultural relations. We are talking here about a grand narrative, driven in part by present-day moral conscience, and deep concerns about on-going issues of poverty, dysfunction and deprivation in many Aboriginal communities, about recognition of and restitution for past wrongs and about reconciliation between black and white Australians. -

Traditional Aboriginal Names BH Shire.Indd

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL PEOPLES NAMES FOR THE NATURAL REGIONS AND FEATURES IN THE HILLS SHIRE LOCAL STUDIES INFORMATION Darug Language Group Darug1 according to Arthur Capell in 19702, was the name of the Aboriginal Peoples language group for most of the Sydney region. The Darug language has been divided into two dialects according to location; coastal and inland - the border between these two dialects was first mentioned by diarist Watkin Tench in 1793 as being just to the west of Parramatta.3 In 1987 Jim Kohen published a dictionary for the Darug inland dialect that was based on words (not place names) recorded by: - 4 Collins, Hunter and Tench in the 1790s, John Rowley in 1878 and R.H. Mathews in 1903. It is likely that the boundary between the coastal clans and inland clans ran north along the Pennant Hills Road ridge, then west along Castle Hill Road and north towards Cattai Ridge Road, Glenorie and then west to the Hawkesbury. Clans were usually named after the place where people lived, or a totem they revered.5 Clans in The Hills Shire would have included the Tuga, Burramatta, Cattai, and Bidji. It seems that the majority probably spoke the inland dialect. Their use of different resources in The Hills Shire’s natural regions of river flats, ridge tops and valleys would have caused them to give these regions special names. Regional Names Reverend William Branwhite Clarke, while headmaster of The King’s School at Parramatta and Sunday preacher to the people of the Castle Hill and Dural areas, recorded in his diary entry for November 6 18406, nine traditional placenames given to him by Narguigui7, chief of South Creek: - Darug Geographic Area Comments & Possible Meaning of Place name 8 1.