Temporal Dynamics of Woodpecker Predation on Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus Planipennis) in the Northeastern U.S.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poland: May 2015

Tropical Birding Trip Report Poland: May 2015 POLAND The Primeval Forests and Marshes of Eastern Europe May 22 – 31, 2015 Tour Leader: Scott Watson Report and Photos by Scott Watson Like a flying sapphire through the Polish marshes, the Bluethroat was a tour favorite. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-0514 [email protected] Page1 Tropical Birding Trip Report Poland: May 2015 Introduction Springtime in Eastern Europe is a magical place, with new foliage, wildflowers galore, breeding resident birds, and new arrivals from Africa. Poland in particular is beautiful this time of year, especially where we visited on this tour; the extensive Biebrza Marshes, and some of the last remaining old-growth forest left in Europe, the primeval forests of Bialowieski National Park, on the border with Belarus. Our tour this year was highly successfully, recording 168 species of birds along with 11 species of mammals. This includes all 10 possible Woodpecker species, many of which we found at their nest holes, using the best local knowledge possible. Local knowledge also got us on track with a nesting Boreal (Tengmalm’s) Owl, while a bit of effort yielded the tricky Eurasian Pygmy-Owl and the trickier Hazel Grouse. We also found 11 species of raptors on this tour, and we even timed it to the day that the technicolored European Bee-eaters arrived back to their breeding grounds. A magical evening was spent watching the display of the rare Great Snipe in the setting sun, with Common Snipe “winnowing” all around and the sounds of breeding Common Redshank and Black-tailed Godwits. -

We West Ham Park

FRIENDS of WEST HAM PARK WE h WEST HAM PARK 2011 Bird Survey Report The Friends of West Ham Park have completed another successful year of bird surveys and the highlight results are listed below. As would be expected, little has changed in the list of birds that can be seen in the Park, but this is the first year since surveys begun in 2006 that a Goldcrest has not been seen, and it is likely that the Park no longer has a breeding population. Sightings of Goldfinches have increased and the resident population of MistleThrush continues to thrive. Although not nesting in the Park in 2011, we have had regular visits from a family of Sparrowhawk and a small flock of Long Tail Tits has continued to delight. A single sighting of Waxwing earlier in the year is the new addition to the list, and the flock was large enough for that bird to make it into the top 20. In order of numbers taken from survey reports the top twenty 2011 bird list is as follows:- • Wood Pigeon (17.5%) • Feral Pigeon (11.9%) • Blackbird (9.3%) • Crow (8.6%) • Starling (8.5%) • Magpie (8.1%) • Blue Tit (5.4%) • Great Tit (4.7%) • Common Gull (4.2%) • Black Headed Gull (3.3%) • Robin (2.7%) • House Sparrow (2.3%) • Mistle Thrush (2.2%) • Pied Wagtail (1.8%) • Long Tail Tit (1.7%) • Waxwing (1.6%) • Redwing (1.2%) • Jay (1%) • Chaffinch (0.9%) • Goldfinch (0.6%) This list accounts for around 97% of all birds seen, but it is important to note that Wren, Song Thrush, Green Woodpecker, Great Spotted Woodpecker and at least a dozen other types of bird are also seen. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

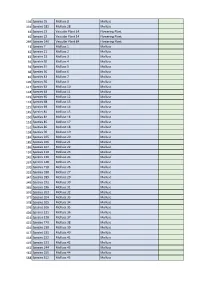

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Landbird Habitat Conservation Strategy – 2020 Revision

Upper Mississippi / Great Lakes Joint Venture Landbird Habitat Conservation Strategy – 2020 Revision Upper Mississippi / Great Lakes Joint Venture Landbird Habitat Conservation Strategy – 2020 Revision Joint Venture Landbird Committee Members: Kelly VanBeek, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Migratory Birds), Co-chair Chris Tonra, The Ohio State University, Co-chair Mohammed Al-Saffar, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Joint Venture) Dave Ewert, American Bird Conservancy Erin Gnass Giese, University of Wisconsin – Green Bay Allisyn-Marie Gillet, Indiana Dept. of Natural Resources Shawn Graff, American Bird Conservancy Jim Herkert, Illinois Audubon Sarah Kendrick, Missouri Dept. of Conservation Mark Nelson, U.S.D.A. Forest Service Katie O’Brien, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Migratory Birds) Greg Soulliere, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Joint Venture) Wayne Thogmartin, U.S. Geological Survey Mike Ward, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Tom Will, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Migratory Birds) Recommended citation: Soulliere, G. J., M. A. Al-Saffar, K. R. VanBeek, C. M. Tonra, M. D. Nelson, D. N. Ewert, T. Will, W. E. Thogmartin, K. E. O’Brien, S. W. Kendrick, A. M. Gillet, J. R. Herkert, E. E. Gnass Giese, M. P. Ward, and S. Graff. 2020. Upper Mississippi / Great Lakes Joint Venture Landbird Habitat Conservation Strategy – 2020 Revision. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bloomington, Minnesota, USA. Cover photo: Whip-poor-will, by Ian Sousa-Cole. TABLE OF CONTENTS STRATEGY SUMMARY ..................................................................................................1 -

Hairy Woodpecker Dryobates Villosus Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata the Hairy Woodpecker Averages Nine and One-Half Class: Aves Inches in Length

hairy woodpecker Dryobates villosus Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The hairy woodpecker averages nine and one-half Class: Aves inches in length. The feathers on its back, outer tail Order: Piciformes feathers, belly, stripes on its head and spots on its wings are white. The head, wing and tail feathers Family: Picidae are black. The male has a small, red patch on the ILLINOIS STATUS back of the head. Unlike the similar downy woodpecker, the hairy woodpecker has a large bill. common, native BEHAVIORS The hairy woodpecker is a common, permanent resident statewide. Nesting takes place from March through June. The nest cavity is dug five to 30 feet above the ground in a dead or live tree. Both sexes excavate the hole over a one- to three-week period. The female deposits three to six white eggs on a nest of wood chips. The male and female take turns incubating the eggs during the day, with only the male incubating at night for the duration of the 11- to 12-day incubation period. One brood is raised per year. The hairy woodpecker lives in woodlands, wooded areas in towns, swamps, orchards and city parks. Its call is a loud “peek.” This woodpecker eats insects, seeds and berries. adult at suet food ILLINOIS RANGE © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. -

Hylocichla Mustelina

Florida Field Naturalist 47(1):25-28, 2019. LICE AND MITES COLLECTED FROM A WOOD THRUSH (Hylocichla mustelina), A BLACK-AND-WHITE WARBLER (Mniotilta varia), A COMMON GRACKLE (Quiscalus quiscula), AND A NORTHERN MOCKINGBIRD (Mimus polyglottos) ON VACA KEY, FLORIDA LAWRENCE J. HRIBAR Florida Keys Mosquito Control District, 503 107th Street, Marathon, Florida 33050 Florida’s bird fauna is species-rich with over 500 species known from the state (Greenlaw et al. 2014). Yet little to nothing is known about the ectoparasite fauna of most species; what is known was summarized by Forrester and Spalding (2003). Since then few contributions have been made to our knowledge. This note reports ectoparasites removed from three birds found dead outside a building on Vaca Key in the City of Marathon, Monroe County, Florida (24.729984, -81.039438) and one bird killed by a moving vehicle also on Vaca Key. All birds were examined for ectoparasites and specimens were handled and prepared for study as in previous reports (Hribar and Miller 2011; Hribar 2013, 2014). Slide-mounted specimens were sent to specialists for identification. The Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina) was once much commoner than it is now; since 1966 its numbers have declined almost 2% per year (Sauer et al. 2012). It is rarely observed in the Florida Keys, and then only in the spring and autumn, during migration (USFWS 1994). Forrester and Spalding (2003) reported no records of ectoparasitic mites from this bird in Florida. An unidentified feather miteAnalges sp. (Analgidae) was recovered from a Wood Thrush in Tennessee (Reeves et al. 2007). -

The Generic Distinction of Pied Woodpeckers

THE GENERIC DISTINCTION OF PIED WOODPECKERS M. RALPH BROWNING, 170 JacksonCreek Drive, Jacksonville,Oregon 97530 ABSTRACT: The ten speciesof New World four-toedwoodpeckers (scalaris, nuttallii, pubescens, villosus, stricklandi, arizonae, borealis, albolarvatus, lignarius,and m ixtusand the two borealthree-toed species (arcticus and tridactylus), currentlycombined in the genusPicoides, differ, in additionto the numberof toes,in modificationsof the skull,ribs, the belly of the pubo-ischio-femoralismuscle, head plumage,and behavior. I recommendthat the genericname Dryobates be reinstituted for the New World four-toedwoodpeckers. There are three generalmorphological groups of pied woodpeckers,a groupof nine four-toedspecies of the New World, a groupof 22 four-toed speciesof the Old World, and a groupof two three-toedspecies straddling bothregions. ! referto thesegroups of piedwoodpeckers beyond as the New World,Old World,and three-toedgroups. The three-toedspecies have long beenin the genusPicoides Lac•p•de, 1799, but the four-toedgroups have been combinedat the genericlevel in differentways. All four-toedpied woodpeckerswere long includedin the genusDryobates Boie, 1826, later changed to Dendrocopos Koch, 1816 an earlier name (Voous 1947, A.O.U. 1947, Peters 1948). Despite the differencein number of toes, Dendrocoposwas combined with Picoidesbecause of generalsimilarities in anatomy (Delacour 1951, Short 1971a), plumage and behavior (Short 1974a), and vocalizations(Winkler and Short 1978). The A.O.U (1976) followedthis mergerof the genera.On the basisof skeletalcharacters Rea (1983) was skepticalof the merger,but he did not providedetails. On the otherhand, Ouellet(1977), concludingthat the two generadiffer in external morphologyand some behaviors and vocalizations, separated the Old World four-toedwoodpeckers in Dendrocoposand three-toedand New World four-toedwoodpeckers in Picoides.The A.O.U. -

Adult Red-Headed Woodpecker Interac- Tion with Bullsnake After Arboreal Nest Depredation

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The Prairie Naturalist Great Plains Natural Science Society 6-2017 ADULT RED-HEADED WOODPECKER INTERAC- TION WITH BULLSNAKE AFTER ARBOREAL NEST DEPREDATION Brittney J. Yohannes James L. Howitz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tpn Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Systems Biology Commons, and the Weed Science Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Natural Science Society at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Prairie Naturalist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Prairie Naturalist 49:23–25; 2017 ADULT RED-HEADED WOODPECKER INTERAC- 100 m away from the first observation. To our knowledge, TION WITH BULLSNAKE AFTER ARBOREAL this is the first documented observation of red-headed wood- NEST DEPREDATION—Nest success rates often are pecker nest depredation by any subspecies of gopher snake, higher among cavity nesting birds than those that nest in and the first documented case of an adult red-headed wood- open cups or on the ground (Martin and Li 1992, Wesołowski pecker actively defending its nest against snake predation. and Tomiłojć 2005). Among cavity nesting birds, woodpeck- On 10 June 2015, we were monitoring red-headed wood- ers have some of the highest rates of nest success (Johnson pecker nests at Cedar Creek Ecosystem Science Reserve in and Kermott 1994). A review of woodpecker nesting ecology East Bethel, MN with a nest cavity camera (IBWO.org, Little across species documented nest success ranging from 0.42 to Rock, Arkansas) and telescoping pole (Crain, Mound City, Il- 1.00 with a median of 0.80 (n = 84 populations), and that pre- linois). -

Southeast Arizona, USA 29Th December 2019 - 11Th January 2020

Southeast Arizona, USA 29th December 2019 - 11th January 2020 By Samuel Perfect Bird Taxonomy for this trip report follows the IOC World Bird List (v 9.2) Site info and abbreviations: Map of SE Arizona including codes for each site mentioned in the text Twin Hills Estates, Tucson (THE) 32.227400, -111.059838 The estate is by private access only. However, there is a trail (Painted Hills Trailhead) at 32.227668, - 111.038959 which offers much the same diversity in a less built up environment. The land in the surrounding area tends to be private with multiple “no trespassing” signs so much of the birding had to be confined to the road or trails. Nevertheless, the environment is largely left to nature and even the gardens incorporate the natural flora, most notably the saguaro cacti. The urban environment hosts Northern Mockingbird, Mourning Dove and House Finch in abundance whilst the trail and rural environments included desert specialities such as Cactus Wren, Phainopepla, Black-throated Sparrow and Gila Woodpecker. Saguaro National Park, Picture Rocks (SNP) 32.254136, -111.197316 Although we remained in the car for much of our visit as we completed the “Loop Drive” we did manage to soak in much of the scenery of the park set in the West Rincon Mountain District and the impressive extent of the cactus forest. Several smaller trails do border the main driving loop, so it was possible to explore further afield where we chose to stop. There is little evidence of human influence besides the roads and trails with the main exception being the visitor centre (see coordinates). -

The Woodcock Volume 3 Issue 3

The Woodcock Volume 3 issue 3 Welcome to ABC The Antioch Bird Club Team extends a hearty welcome to previous and new readers to this edition of The Woodcock! This is your one stop to find out all things Antioch Bird Club (ABC). Each month within its pages you will find ABC news and updates, previous event highlights, upcoming event descriptions, and new ways to get involved. Sometimes there will be special editions of this newsletter as well, such as the Global Big Year edition coming soon! Have a creative idea for an event, trip, or activity? We are always accepting suggestions just email an ABC team member or stop by our next meeting (4:15pm February 28th; Rm 231). We are excited to learn about our club members’ diverse passions, and we look forward to finding new ways to connect to each other through birds. As a supporter of ABC, you have made a statement for bird conservation locally and globally; thank you! ABC members leading a guided community bird walk at Horatio Colony Preserve in 2018. ABC News Meet the ABC Team ABC welcomes back Steven Lamonde and Rachel Yurchisin as ABC Coordinators for the spring semester. Steven is a third-year Con Bio student studying Golden-winged Warblers in Vermont, and Rachel is a second-year Con Bio student working on Liz Willey’s turtle conservation project. ABC brought on two new assistants this semester, Kim Snyder and Jessica Poulin! Kim is a first-year Con Bio student and has already brainstormed some exciting new ideas for ABC projects and events. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Rules

21282 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR United States and the Government of United States or U.S. territories as a Canada Amending the 1916 Convention result of recent taxonomic changes; Fish and Wildlife Service between the United Kingdom and the (8) Change the common (English) United States of America for the names of 43 species to conform to 50 CFR Part 10 Protection of Migratory Birds, Sen. accepted use; and (9) Change the scientific names of 135 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; Treaty Doc. 104–28 (December 14, FXMB 12320900000//201//FF09M29000] 1995); species to conform to accepted use. (2) Mexico: Convention between the The List of Migratory Birds (50 CFR RIN 1018–BC67 United States and Mexico for the 10.13) was last revised on November 1, Protection of Migratory Birds and Game 2013 (78 FR 65844). The amendments in General Provisions; Revised List of this rule were necessitated by nine Migratory Birds Mammals, February 7, 1936, 50 Stat. 1311 (T.S. No. 912), as amended by published supplements to the 7th (1998) AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Protocol with Mexico amending edition of the American Ornithologists’ Interior. Convention for Protection of Migratory Union (AOU, now recognized as the American Ornithological Society (AOS)) ACTION: Final rule. Birds and Game Mammals, Sen. Treaty Doc. 105–26 (May 5, 1997); Check-list of North American Birds (AOU 2011, AOU 2012, AOU 2013, SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and (3) Japan: Convention between the AOU 2014, AOU 2015, AOU 2016, AOS Wildlife Service (Service), revise the Government of the United States of 2017, AOS 2018, and AOS 2019) and List of Migratory Birds protected by the America and the Government of Japan the 2017 publication of the Clements Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) by for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Checklist of Birds of the World both adding and removing species. -

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species 02 05 Restore Canada Jay as the English name of Perisoreus canadensis 03 13 Recognize two genera in Stercorariidae 04 15 Split Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) into two species 05 19 Split Pseudobulweria from Pterodroma 06 25 Add Tadorna tadorna (Common Shelduck) to the Checklist 07 27 Add three species to the U.S. list 08 29 Change the English names of the two species of Gallinula that occur in our area 09 32 Change the English name of Leistes militaris to Red-breasted Meadowlark 10 35 Revise generic assignments of woodpeckers of the genus Picoides 11 39 Split the storm-petrels (Hydrobatidae) into two families 1 2018-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 280 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species Effect on NACC: This proposal would change the species circumscription of Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus by splitting it into four species. The form that occurs in the NACC area is nominate pacificus, so the current species account would remain unchanged except for the distributional statement and notes. Background: The Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus was until recently (e.g., Chantler 1999, 2000) considered to consist of four subspecies: pacificus, kanoi, cooki, and leuconyx. Nominate pacificus is highly migratory, breeding from Siberia south to northern China and Japan, and wintering in Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The other subspecies are either residents or short distance migrants: kanoi, which breeds from Taiwan west to SE Tibet and appears to winter as far south as southeast Asia.