The New Energy System in the Mexican Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Searching for a New Constitutional Model for East-Central Europe

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 1991 Searching for a New Constitutional Model for East-Central Europe Rett R. Ludwikowski The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Rett. R. Ludwikowski, Searching for a New Constitutional Model for East-Central Europe, 17 SYRACUSE J. INT’L L. & COM. 91 (1991). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEARCHING FOR A NEW CONSTITUTIONAL MODEL FOR EAST-CENTRAL EUROPE Rett R. Ludwikowski* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 92 II. CONSTITUTIONAL TRADITIONS: THE OVERVIEW ....... 93 A. Polish Constitutional Traditions .................... 93 1. The Constitution of May 3, 1791 ............... 94 2. Polish Constitutions in the Period of the Partitions ...................................... 96 3. Constitutions of the Restored Polish State After World War 1 (1918-1939) ...................... 100 B. Soviet Constitutions ................................ 102 1. Constitutional Legacy of Tsarist Russia ......... 102 2. The Soviet Revolutionary Constitution of 1918.. 104 3. The First Post-Revolutionary Constitution of 1924 ........................................... 107 4. The Stalin Constitution of 1936 ................ 109 5. The Post-Stalinist Constitution of 1977 ......... 112 C. Outline of the Constitutional History of Romania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary ............. 114 III. CONSTITUTIONAL LEGACY: CONFRONTATION OF EAST AND W EST ............................................ -

Declaration of the Vii Forum of the Parliamentary Front Against Hunger in Latin America and the Caribbean - Mexico City

DECLARATION OF THE VII FORUM OF THE PARLIAMENTARY FRONT AGAINST HUNGER IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN - MEXICO CITY We, Members of the Parliaments and members of the Latin America and the Caribbean Parliamentary Front against Hunger (PFH), with the valuable participation of parliamentarians from Africa and Europe, gathered in 1 Mexico City on November 9, 10 and 11, 2016, on the occasion of the 7th Forum of the Parliamentary Front against Hunger in Latin America and the Caribbean. CONSIDERING That the agenda of the States set the focus on the fight against hunger and malnutrition and on the food sovereignty of the nations, as it is stated in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and in its Goal 2 “End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture,” as well as in the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, which came into force on November 4th, 2016; also, considering that in the Latin America and the Caribbean parliaments, laws on food and nutrition security and sovereignty have been approved and are under discussion. That in the above-mentioned Agenda the legislative powers are crucial agents to end hunger and malnutrition, as it is reflected in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, when noting that the Members of the Parliaments perform a key role in the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) by “enacting legislation, approving budgets, and ensuring accountability”. That in the Special Declaration on the “Plan for Food Security, Nutrition and Hunger Eradication” of January 27, 2016, announced on the occasion of the IV Latin America and the Caribbean States Summit (CELAC) held in Quito, Ecuador, the Heads of State and Government of the region reaffirmed their commitment to the eradication of hunger and malnutrition, as an essential element in order to achieve sustainable development. -

Comparing Power— an Appraisal of Comparative Government and Politics AP Comparative and Politics Curriculum 2 Teachers 2019

Citizen U Presents: Comparing Power— An Appraisal of Comparative Government and Politics AP Comparative and Politics Curriculum 2 Teachers 2019 Big Ideas in AP Comparative Government and Politics* 1. POWER AND AUTHORITY (PAU)* 2. LEGITIMACY AND STABILTY (LEG)* 3. DEMOCRATIZATION (DEM)* 4. INTERNAL/EXTERNAL FORCES (IEF)* 5. METHODS of POLITICAL ANALYSIS (MPA)* Unit 1: Political Systems, Regimes, and Governments* MPA— Enduring Understanding: Empirical data is important in identifying and explaining political behavior of individuals and groups.* 1.1 Explain how political scientists construct knowledge and communicate inferences and explanations about political systems, institutional interactions, and behavior* Analysis of quantitative and qualitative information (including charts, tables, graphs, speeches, foundational documents, political cartoons, maps, and political commentaries) is a way to make comparisons between and inferences about course countries.* Analyzing empirical data using quantitative methods facilitates making comparisons among and inferences about course countries.* One practice of political scientists is to use empirical data to identify and explain political behavior of individuals and groups. Empirical data is information from observation or experimentation. By using empirical data, political scientists can construct knowledge and communicate inferences and explanations about political systems, institutional interactions, and behavior. Empirical data such as statistics from sources such as governmental reports, polls, -

CONSTI INGLES SEPT 2010.Pdf

First edition: August 2005 Second edition: November 2008 Third edition: March 2010 Fourth edition: August 2010 All rights reserved. © Mexican Supreme Court Av. José María Pino Suárez, No. 2 C.P. 06065, México, D.F. Printed in Mexico Translators: Dr. José Antonio Caballero Juárez and Lic. Laura Martín del Campo Steta. Translation updated by: Lic. Sergio Alonso Rodríguez Narváez and Estefanía Vela The update, edition, and design of this publication was made by the General Management of the Coordination on Compilation and Systematization of Theses of the Mexican Supreme Court. Mexican Supreme Court Justice Guillermo I. Ortiz Mayagoitia President First Chamber Justice José de Jesús Gudiño Pelayo President Justice José Ramón Cossío Díaz Justice Olga María Sánchez Cordero de García Villegas Justice Juan N. Silva Meza Justice Arturo Zaldívar Lelo de Larrea Second Chamber Justice Sergio Salvador Aguirre Anguiano President Justice Luis María Aguilar Morales Justice José Fernando Franco González Salas Justice Margarita Beatriz Luna Ramos Justice Sergio A. Valls Hernández Publications, Social Communication, Cultural Diffusion and Institutional Relations Committee Justice Guillermo I. Ortiz Mayagoitia Justice Sergio A. Valls Hernández Justice Arturo Zaldívar Lelo de Larrea Editorial Committee Mtro. Alfonso Oñate Laborde Technical Legal Secretary Mtra. Cielito Bolívar Galindo General Director of the Theses Compilation and Systematization Bureau Lic. Gustavo Addad Santiago General Director of Diffusion Judge Juan José Franco Luna General Director of the Houses of Juridical Culture and Historical Studies Dr. Salvador Cárdenas Gutiérrez Director of Historical Research CONTENT FOREWORD ................................... IX TITLE ONE CHAPTER ONE Fundamental rights ............................................1 CHAPTER TWO Mexican nationals ............................................ 95 CHAPTER THREE Aliens ................................................................ 99 CHAPTER FOUR Mexican citizens ............................................ -

Mexican Elections in 2018

Mexican elections in 2018: What to expect when you're expecting? . The upcoming electoral process of 2018 in Mexico is one of the September 15, 2017 geopolitical risks to the outlook www.banorte.com . We believe that it is still too early to call the electoral result www.ixe.com.mx @analisis_fundam . In fact, polls still show a high degree of indecision among the population Delia Paredes . We expect a tight race, albeit with a limited impact on the Executive Director of Economic Analysis markets [email protected] . This election is particularly important since it will be one of the first times many of the new laws enacted as part of 2014’s electoral reform will be carried out, although some will come into effect later: (1) Senators and Representatives elected in 2018 might be reelected; (2) Possibility of coalition governments and independent candidates; (3) Changes in the regime of political parties; (4) New provisions for the National Electoral Institute (INE); and (5) Provisions regarding popular consultations . There are mechanisms established in case of a contested election . In addition, at the end of this year there are also two important processes: (1) The transition of power in Banxico; and (2) 2018’s budget process Mexican elections in 2018 What to expect when you're expecting? The electoral process in Mexico is one of the geopolitical risks for the scenario of the coming year. After the delivery of the 2018 fiscal budget on September 8th, the 2018 electoral process will now be the center of attention with parties already taking some steps in this direction. -

The Value of TRUTH a Third of the Way

The value of TRUTH A third of the way MARCH 2021 THE VALUE OF TRUTH :: 1 https://www.elmundo.es/america/2013/01/08/mexico/1357679051html Is a non-profit, non governmental organization thats is structured by a Council built up of people with an outstanding track record, with high ethical and pro- fessional level, which have national and international recognition and with a firm commitment to democratic and freedom principles. The Council is structured with an Executive Committee, and Advisory Committee of Specialists and a Comunication Advisory Committee, and a Executive Director coordinates the operation of these three Committees. One of the main objectives is the collection of reliable and independent informa- tion on the key variables of our economic, political and sociocultural context in order to diagnose, with a good degree of certainty, the state where the country is located. Vital Signs intends to serve as a light to show the direction that Mexico is taking through the dissemination of quarterly reports, with a national and international scope, to alert society and the policy makers of the wide variety of problems that require special attention. Weak or absent pulse can have many causes and represents a medical emergency. The more frequent causes are the heart attack and the shock condition. Heart attack occurs when the heart stops beating. The shock condition occurs when the organism suffers a considerable deterioration, wich causes a weak pulse, fast heartbeat, shallow, breathing and loss of consciousness. It can be caused by different factors. Vital Signs weaken and you have to be constantly taking the pulse. -

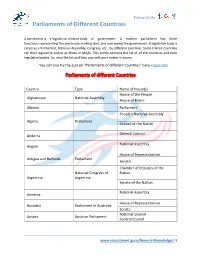

Parliaments of Different Countries

Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries A parliament is a legislative, elected body of government. A modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government. A legislative body is called as a Parliament, National Assembly, Congress, etc., by different countries. Some Islamic countries call their legislative bodies as Shora or Majlis. This article contains the list of all the countries and their legislative bodies. So, read the list and help yourself score better in exams. You can also try the quiz on “Parliaments of different Countries” here – Quiz Link Parliaments of different Countries Country Type Name of house(s) House of the People Afghanistan National Assembly House of Elders Albania Parliament People's National Assembly Algeria Parliament Council of the Nation General Council Andorra National Assembly Angola House of Representatives Antigua and Barbuda Parliament Senate Chamber of Deputies of the National Congress of Nation Argentina Argentina Senate of the Nation National Assembly Armenia House of Representatives Australia Parliament of Australia Senate National Council Austria Austrian Parliament Federal Council www.recruitment.guru/General-Knowledge/|1 Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries Azerbaijan National Assembly House of Assembly Bahamas, The Parliament Senate Council of Representatives Bahrain National Assembly Consultative Council National Parliament Bangladesh House of Assembly Barbados Parliament Senate House of Representatives National Assembly -

European Union Election Observation Mission Mexico 2006 FINAL REPORT

Final Report European Union Election Observation Mission Mexico 2006 FINAL REPORT This report was produced by the EU Election Observation Mission and presents the EU EOM’s findings on the 2006 Presidential and Parliamentary elections in Mexico. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the Commission. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. M E X I C O FINAL REPORT PRESIDENTIAL AND PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 2 July 2006 EUROPEAN UNION ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION 23 November 2006, Mexico City/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENT I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 II. INTRODUCTION 4 III. POLITICAL BACKGROUNG 5 A. Political Context 5 B. The Political Parties and Candidates 7 IV. LEGAL ISSUES 9 A. Political Organization of Mexico 9 B. Constitutional and Legal Framework 10 V. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION 11 A. Structure of the Election Administration 11 B. Performance of IFE 12 C. The General Council 13 VI. VOTER REGISTRATION 14 VII. REGISTRATION OF NATIONAL POLITICAL PARTIES 16 VIII. CANDIDATE REGISTRATION 17 IX. VOTING BY MEXICANS LIVING ABROAD 18 X. PARTICIPATION OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLE 19 XI. THE ‘CASILLAS ESPECIALES’ 20 XII. CIVIC AND VOTER EDUCATION 22 XIII. ELECTION CAMPAIGN 22 A. Campaign Environment and Conditions 22 B. Use of State Resources 23 C. Financing of Political Parties 25 D. Campaign Financing 26 XIV. PARTICIPATION OF CIVIL SOCIETY AND OBSERVATION 28 XV. MEDIA 29 A. Freedom of the Press 30 B. Legal Framework 31 C. -

Reform in Mexico 2014 Political-Electoral Reform in Mexico

2014 Political Electoral Reform in Mexico 2014 Political-Electoral Reform In Mexico Tribunal Electoral del Poder Judicial de la Federación Carlota Armero No.5000, Col. CTM Culhuacán, Delegción Coyoacán, C.P. 04480. México D.F. Teléfonos: 01(55) 5728-2300 / 01(55) 5484-5410 www.te.gob.mx Coordinación: Centro de Capacitación Electoral ISBN: En trámite Publicado en México 2014 POLITICAL-ELECTORAL REFORM IN MEXICO CONTENTS 1. System of government . 5 1.1 Coalition government . 5 1.2 Date of the Election Day and of taking office . 5 1.3 Ratification of the cabinet . 5 2. Reelection . 7 3. Electoral authorities . 8 3.1 General Council of INE . 8 3.2 Powers of INE. 8 3.3 Local electoral administrative authorities . 10 3.4 Electoral Tribunal of the Federal Judiciary . 11 3.5 Local electoral jurisdictional authorities . .12 4. Party system . 13 4.1 Loss of registration . 13 4.2 Coalitions . 13 4.3 Pre-campaigns . 14 4.4 Gender affirmative action . 15 4.5 Party ballot access . 15 4.6 Internal democracy and intraparty justice . .16 3 2014 Political-Electoral Reform in Mexico 5. Independent candidates . 18 5.1 Rights of the independent candidates . 19 5.2 Obligations of the independent candidates . 20 5.3 Financing and auditing of the independent candidates . 20 6. Financing and auditing . 22 6.1 Political party financing . 22 6.2 Campaign spending control . 23 6.3 Grounds for invalidity related to the financial aspects of the electoral process . 25 7. Participation in campaigns . 26 7.1 Political communication . .26 7.2 Grounds for invalidity related to media access . -

Download PDF Arrow Forward

SMART BORDER COALITION™ San Diego-Tijuana MID-YEAR PROGRESS REPORT-2016 www.smartbordercoalition.com A Wall That Divides Us. A Goal to Unite Us. SMART BORDER COALITION Members of the Board 2016 Malin Burnham/Jose Larroque, Co-Chairs Jose Galicot Gaston Luken Eduardo Acosta Ted Gildred III Matt Newsome Raymundo Arnaiz Dave Hester JC Thomas Lorenzo Berho Russ Jones Mary Walshok Malin Burnham Mohammad Karbasi Steve Williams Frank Carrillo Pradeep Khosla Honorary Rafael Carrillo Pablo Koziner Jorge Astiazaran James Clark Jorge Kuri Marcela Celorio Salomon Cohen Elias Laniado Greg Cox Alberto Coppel Jose Larroque Kevin Faulconer Jose Fimbres Jeff Light William Ostick “OPPORTUNITY COMES FROM A SEAMLESS INTERNATIONAL REGION WHERE ALL CITIZENS WORK TOGETHER FOR MUTUAL ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL PROGRESS” MID-YEAR PROGRESS REPORT 2016 Secure and efficient border crossings are the primary goal of the Coalition. The Coalition works with existing stakeholders in both the public and private sectors to coordinate regional border efficiency efforts not duplicate them. Aquí Empiezan Las Patrias/The Countries Begin Here—Where the Border Meets the Pacific WHY THE BORDER MATTERS The United States is both Mexico’s largest export and largest import market. Hundreds of thousands or people cross the shared 2000-mile border daily During the time we spend on an SBC Board of Directors luncheon, the United States and Mexico will have traded more than $60 million worth of goods and services. The daily United States trade total with is Mexico is more than $1.5 billion supporting jobs in both countries. –courtesy of Consul General Will Ostick SAN DIEGO/TIJUANA BORDER ACCOMPLISHMENTS 1. -

Elections in Mexico July 1 General Elections

Elections in Mexico July 1 General Elections Frequently Asked Questions Latin America and the Caribbean International Foundation for Electoral Systems 1850 K Street, NW | Fifth Floor | Washington, DC 20006 | www.IFES.org June 27, 2012 Table of Contents When are elections in Mexico? ..................................................................................................................... 1 When does the electoral process begin? ...................................................................................................... 1 Who will Mexicans elect in the 2012 federal elections? .............................................................................. 1 What is Mexico’s electoral system? .............................................................................................................. 2 Who is running for president? ...................................................................................................................... 2 How is election administration structured in Mexico? ................................................................................. 3 Who will vote? .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Can Mexicans who reside abroad vote in the elections? ............................................................................. 3 When are preliminary election results released? ......................................................................................... 4 When are -

The Separation of Powers in Mexico

Duquesne Law Review Volume 47 Number 4 Separation of Powers in the Article 6 Americas ... and Beyond: Symposium Issue 2009 The Separation of Powers in Mexico Jose Gamas Torruco Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jose G. Torruco, The Separation of Powers in Mexico, 47 Duq. L. Rev. 761 (2009). Available at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr/vol47/iss4/6 This Symposium Article is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Duquesne Law Review by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. The Separation of Powers in Mexico Josg Gamas Torruco* I. CONSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS .................................. 762 II. H ISTORY ......................................................................... 765 III. PRESIDENT-PARTY SYSTEM ........................................... 770 IV. THE "TRANSITION" ........................................................ 776 V. PRESIDENT-CONGRESS .................................................. 777 A . B alances............................................................. 777 1. Intervention by the Presidentin the Legislative Process ................................ 777 2. ExtraordinaryPowers to Legislate ................................................ 778 i. Suspension of Human Rights .... 778 ii. Export and Import Tariffs ......... 778 iii. Health Emergencies ................... 778 3. Duty to Inform....................................... 779 4. FinancialActs ......................................