The Midnight Rose and It’S Rather a Mysterious Plant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Childhood Professionals and Changing Families

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 289 609 PS 017 043 AUTHOR Weiss, Heather B. TITLE Early Childhood Professionals and Changing Families. PUB DATE 10 Apr 87 NOTE 22p.; Paper presented at the Meeting of the Anchorage Association for the Education of Young Children (Anchorage, AK, April 10, 1987). PUB TYPE Viewpoints (120) -- Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Child Caregivers; *Community Action; Early Childhood Education; *Family Programs; Parent Teacher Cooperation; *Preschool Teachers; *Program Implementation; *Public Policy IDENTIFIERS *Alaska; Research Results ABSTRACT Early childl-ood educators are advised to confront difficulties arising from Alaska's economic problems by establishing coalitions between families with young children and service providers, with the intention of creating new programs and maintaining existing family support and education programs. Evidence of the desirability of a wide range of family-provider partnerships is summarized in:(1) discussions of the appeal of such programs from the perspective of public policy; and (2) reports of findings from research and evaluation studies of program effectiveness and the role of social support in child rearing. Subsequent discussion describes desired features of such coalitions and specifies key principles that und.rlie them. Ihe concluding section of the presentation details a research-based plan which conference participants might (evelop to implement partnership programs on a pilot basis, (RH) *********************************************************************** -

WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, APRIL 2019 WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS, 1970–1982 A BRIEF WARNER BROS. / WEA HISTORY WIKIPEDIA TELLS US THAT... WEA’S ROOTS DATE BACK TO THE FOUNDING OF WARNER BROS. RECORDS IN 1958 AS A DIVISION OF WARNER BROS. PICTURES. IN 1963, WARNER BROS. RECORDS PURCHASED FRANK SINATRA’S REPRISE RECORDS. AFTER WARNER BROS. WAS SOLD TO SEVEN ARTS PRODUCTIONS IN 1967 (FORMING WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS), IT PURCHASED ATLANTIC RECORDS AS WELL AS ITS SUBSIDIARY ATCO RECORDS. IN 1969, THE WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS COMPANY WAS SOLD TO THE KINNEY NATIONAL COMPANY. KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL (LATER CHANGING ITS NAME TO WARNER COMMUNICATIONS) COMBINED THE OPERATIONS OF ALL OF ITS RECORD LABELS, AND KINNEY CEO STEVE ROSS LED THE GROUP THROUGH ITS MOST SUCCESSFUL PERIOD, UNTIL HIS DEATH IN 1994. IN 1969, ELEKTRA RECORDS BOSS JAC HOLZMAN APPROACHED ATLANTIC'S JERRY WEXLER TO SET UP A JOINT DISTRIBUTION NETWORK FOR WARNER, ELEKTRA, AND ATLANTIC. ATLANTIC RECORDS ALSO AGREED TO ASSIST WARNER BROS. IN ESTABLISHING OVERSEAS DIVISIONS, BUT RIVALRY WAS STILL A FACTOR —WHEN WARNER EXECUTIVE PHIL ROSE ARRIVED IN AUSTRALIA TO BEGIN SETTING UP AN AUSTRALIAN SUBSIDIARY, HE DISCOVERED THAT ONLY ONE WEEK EARLIER ATLANTIC HAD SIGNED A NEW FOUR-YEAR DISTRIBUTION DEAL WITH FESTIVAL RECORDS. IN MARCH 1972, KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL WAS RENAMED WEA MUSIC INTERNATIONAL. DURING THE 1970S, THE WARNER GROUP BUILT UP A COMMANDING POSITION IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY. IN 1970, IT BOUGHT ELEKTRA (FOUNDED BY HOLZMAN IN 1950) FOR $10 MILLION, ALONG WITH THE BUDGET CLASSICAL MUSIC LABEL NONESUCH RECORDS. -

Welcome, We Have Been Archiving This Data for Research and Preservation of These Early Discs. ALL MP3 Files Can Be Sent to You B

Welcome, To our MP3 archive section. These listings are recordings taken from early 78 & 45 rpm records. We have been archiving this data for research and preservation of these early discs. ALL MP3 files can be sent to you by email - $2.00 per song Scroll until you locate what you would like to have sent to you, via email. If you don't use Paypal you can send payment to us at: RECORDSMITH, 2803 IRISDALE AVE RICHMOND, VA 23228 Order by ARTIST & TITLE [email protected] S.O.S. Band - Finest, The 1983 S.O.S. Band - Just Be Good To Me 1984 S.O.S. Band - Just The Way You Like It 1980 S.O.S. Band - Take Your Time (Do It Right) 1983 S.O.S. Band - Tell Me If You Still Care 1999 S.O.S. Band with UWF All-Stars - Girls Night Out S.O.U.L. - On Top Of The World 1992 S.O.U.L. S.Y.S.T.E.M. with M. Visage - It's Gonna Be A Love. 1995 Saadiq, Raphael - Ask Of You 1999 Saadiq, Raphael with Q-Tip - Get Involved 1981 Sad Cafe - La-Di-Da 1979 Sad Cafe - Run Home Girl 1996 Sadat X - Hang 'Em High 1937 Saddle Tramps - Hot As I Am 1937 (Voc 3708) Saddler, Janice & Jammers - My Baby's Coming Home To Stay 1993 Sade - Kiss Of Life 1986 Sade - Never As Good As The First Time 1992 Sade - No Ordinary Love 1988 Sade - Paradise 1985 Sade - Smooth Operator 1985 Sade - Sweetest Taboo, The 1985 Sade - Your Love Is King Sadina - It Comes And Goes 1966 Sadler, Barry - A Team 1966 Sadler, Barry - Ballad Of The Green Berets 1960 Safaris - Girl With The Story In Her Eyes 1960 Safaris - Image Of A Girl 1963 Safaris - Kick Out 1988 Sa-Fire - Boy, I've Been Told 1989 Sa-Fire - Gonna Make it 1989 Sa-Fire - I Will Survive 1991 Sa-Fire - Made Up My Mind 1989 Sa-Fire - Thinking Of You 1983 Saga - Flyer, The 1982 Saga - On The Loose 1983 Saga - Wind Him Up 1994 Sagat - (Funk Dat) 1977 Sager, Carol Bayer - I'd Rather Leave While I'm In Love 1977 1981 Sager, Carol Bayer - Stronger Than Before 1977 Sager, Carol Bayer - You're Moving Out Today 1969 Sagittarius - In My Room 1967 Sagittarius - My World Fell Down 1969 Sagittarius (feat. -

Stephen Stills Discography Music

Stephen stills discography music Find Stephen Stills discography, albums and singles on AllMusic. and Crosby, Stills & Nash, two of pop music's most successful and enduring groups. Stephen Stills discography and songs: Music profile for Stephen Stills, born January 3, Albums include Super Session, Manassas, and Stephen Stills. Stephen Stills Has a Message for Donald Trump. Hear "Look Each Other In The Eye," a song that rails against Republican candidate Donald Trump's vanity and Stephen Stills Has a Message · Stephen Stills And Judy · Tour Dates · News. Ultimate Classic Rock counts down the best solo songs by Stephen Stills. Still, as you'll see in a list of Top 10 Stephen Stills Songs which steers .. From: 'Stephen Stills 2′ () . It's not “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” but it's as close as Stills gets without help from his .. The Most Inflluential Grunge Albums. List of the best Stephen Stills albums, including pictures of the album covers when av music The Best Stephen Stills Albums of All Time 3. 8 1. Stephen Stills 2 is listed (or ranked) 3 on the list The Best Stephen Super Session Stephen Stills, Mike Bloomfield, Al Kooper Just Roll Tape- April 26th, Stephen Stills. Church (part of someone) 4. Old times Music. "Love The One You're With" by Stephen Stills. Visit 's Stephen Stills Store to shop for Stephen Stills albums (CD, MP3, Vinyl), concert tickets, and other Stephen Stills-related products (DVDs, Books, T-shirts). Also explore Digital Music. Select the .. Stephen Stills 2. Stephen Stills . by Stephen Stills on Just Roll Tape - April 26th · Treetop Flyer. -

If I Say If: the Poems and Short Stories of Boris Vian

Welcome to the electronic edition of If I Say If: The Poems and Short Stories of Boris Vian. The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page. Click on this anytime to return to the contents. You can also add your own bookmarks. Each chapter heading in the contents table is clickable and will take you direct to the chapter. Return using the contents link in the bookmarks. The whole document is fully searchable. Enjoy. If I Say If The high-quality paperback edition is available for purchase online: https://shop.adelaide.edu.au/ CONTENTS Foreword ix Marc Lapprand Boris Vian: A Life in Paradox 1 Alistair Rolls, John West-Sooby and Jean Fornasiero Note on the Texts 13 Part I: The Poetry of Boris Vian 15 Translated by Maria Freij I wouldn’t wanna die 17 Why do I live 20 Life is like a tooth 21 There was a brass lamp 22 When the wind’s blowing through my skull 23 I’m no longer at ease 24 If I were a poet-o 25 I bought some bread, stale and all 26 There is sunshine in the street 27 A stark naked man was walking 28 My rapier hurts 29 They are breaking the world 30 Yet another 32 I should like 34 If I say if 35 If I Say If A poet 36 If poets weren’t such fools 37 It would be there, so heavy 39 There are those who have dear little trumpets 41 I want a life shaped like a fishbone 42 One day 43 Everything has been said a hundred times 44 I shall die of a cancer of the spine 45 Rereading Vian: A Poetics of Partial Disclosure 47 Alistair Rolls Part II: The Short Stories of Boris Vian 63 Translated by Peter Hodges Martin called… -

PREMIERE RADIO for WEEK ENDING April 3, 1971 15260 VENTURA BOULEVARD CYCLE 711 PROGRAM 14 of 13 SHERMAN OAKS, CALIFORNIA 91403 HOUR 1 (818) 377-5300 Page No

PREMIERE RADIO FOR WEEK ENDING April 3, 1971 15260 VENTURA BOULEVARD CYCLE 711 PROGRAM 14 OF 13 SHERMAN OAKS, CALIFORNIA 91403 HOUR 1 (818) 377-5300 Page No. 1 SCHEDULED ACTUAL RUNNING ELEMENT START TIME TIME TIME THEME AND OPENING OF HOUR 1 TALK UNIT #40. ASK ME NO QUESTIONS - B.B. KING 6:31 #39. IF - BREAD LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST LOCAL INSERT: C-1 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #38. BABY LET ME KISS YOU - KING FLOYD 2:29 LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST LOCAL INSERT: C-2 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #37. SIT YOURSELF DOWN - STEPHEN STILLS 5:43 EXTRA: BABY LOVE - SUPREMES LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST LOCAL INSERT: C-3 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #36. IF YOU COULD READ MY MIND - GORFON LIGHTFOOT 3:54 LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST LOCAL INSERT: C-4 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #35. WHERE DID THEY GO LORD - ELVIS PRESLEY 5:39 #34. DREAM BABY (HOW LONG MUST I DREAM) - GLEN CAMPBELL LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST LOCAL INSERT: C-5 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #33. STAY AWHILE - BELLS 6:24 #32. WE CAN WORK IT OUT - STEVIE WONDER LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST LOCAL INSERT: C-6 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #31. PUT YOUR HAND IN THE HAND - OCEAN 5:58 #30. MAMA'S PEARL - JACKSON 5 LOGO: HITS FROM COAST TO COAST LOCAL INSERT: C-6 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #29. SOUL POWER - JAMES BROWN 3:13 LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST LOCAL INSERT: C-7 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #28. -

Wishing on Dandelions a Novel

Wishing On Dandelions A novel By Mary E. DeMuth Mary E. DeMuth, Inc. P.O. Box 1503 Rockwall, TX 75087 Copyright 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without written permission from Mary E. DeMuth, Inc, P.O. Box 1503, Rockwall, TX 75087, www.marydemuth.com. Cover design Mary DeMuth Cover photo by Mary E. DeMuth This novel is a work of fiction. Any people, places or events that may resemble reality are simply coincidental. The book is entirely from the imagination of the author. Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture quotations in this publication are taken from the King James Version (KJV). Other version used: the New American Standard Bible (NASB), copyright The Lockman Foundation 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data DeMuth, Mary E., 1967- Watching the Tree Limbs / Mary E. DeMuth p. cm. Includes biographical references. ISBN-10: 0983436754 ISBN-13: 978-0-9834367-5-1 1. Girls—fiction, 2. Rape victims—fiction 1. Title To those who wish for healing . Acknowledgements atrick, it blesses me that you read my novels, even when you don’t read novels, Pand tell me how they move your heart. I love you. I couldn’t have written this book without the insight of my critique group, Life Sentence. Leslie and D’Ann, thank you for plowing through the first draft with me and offering valuable words of encouragement and clarity. I love our Wednesday phone calls. I only wish I could import you to France! Thank you, prayer team, for faithfully praying -

Gonzaga Bulletin

Only Runoff Fee Raise Fails, 464-321 GANGLE, TAYLOR IN RUNOFF Huckabee, Schweda, Vanairsdale Nab Posts PRESIDENT JNK* CLASS PRESIDENT Paul Ritchie 13© Vmce Heiberholt M5X George Hart 7$ FINANCIAL VICE PRESIDENT Al Dembac 139 JUNIOR CLASS VICE PRESIDENT David Tayloi MOX Dentin Van A.rsdale 530X Jane McNulty 111 Roie Gangie 236X Mike Gilmce 222 Anne Louise Paiheco 147X Mike Ba.ley 177 SENIOR CtASS PRESIDENT S Vi-OVORE CLASS PRESIDENT RRST VICE-PRESIDENT Ed Magan 49 John Timm 329 Bill OShaughnessv 151 Bill Jones 44 E.-l Delehanty 171X Ann Miles 87 Dennis Hone U6X Greg Huckaoee S1U SOPHOMOM VICE PRESIDENT SENIOR CLASS ViCE PRESIDENT Dan Hogan l$JX SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT M^k Bellas* 140X I'-.I o Mooie 151 Greg Hershoir 270 Peie Schweda 601X Runoff Today "Marge" Tonight Koaoffs for student body r«m t aldaroia'> "Margo and offic-ert are betflg beld today Me' opens tonight ID (ii'Bc from X a.m. to 4 p.m in the Hu-s.|| Theatre al X p m All Informal LouBge (Lower MM Hf oar dollar and ticket* COG). Let your student Gonzaga Bulletin •m being >..ld in Ad Hi and at (hf door tw Ion shin*lini> K u w r D m r D 1 represent GONZAGA UNIVERSITY SPOKANE WASHINGTON you-VOTF' Volume LXIl -No^be' 71-72 Spurs Tomorrow Night Arise Early Hawaiians Will Host The jangle of spurs and spiked headdresses distinguish the 30 new Spur electees, routed out of bed earl) Wednesday morning to begin their round of initiation activities Seventh Annual Luau The freshman girls chosen •!•> The Spokane KIKHII of the Cog will be transformed Saturdav next year s Spurs are Toni night into the Wonderful World ol Aloha for the Hawaiian Club s Valentine, Debbie Reynolds, seventh annual luau Paula Sullivan. -

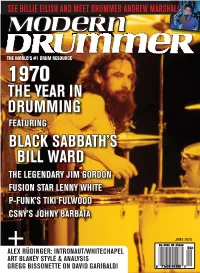

Black Sabbath's Bill Ward the Year in Drumming

SEE BILLIE EILISH AND MEET DRUMMER ANDREW MARSHALL! THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM RESOURCE 1970 THE YEAR IN DRUMMING FEATURING BLACK SABBATH’S BILL WARD THE LEGENDARY JIM GORDON FUSION STAR LENNY WHITE P-FUNK’S TIKI FULWOOD CSNY’S JOHNY BARBATA + JUNE 2020 ALEX RÜDINGER: INTRONAUT/WHITECHAPEL ART BLAKEY STYLE & ANALYSIS GREGG BISSONETTE ON DAVID GARIBALDI An Icon for an Icon. DW is proud to present the long-awaited Collector’s Series® Jim Keltner Icon Snare Drum. Precise, laser-cut wood inlays are meticulously applied over an all-maple 11-ply VLT shell. A collectible meets highly-playable instrument that will always endure. Legendary, timeless, iconic. To experience more, visit dwdrums.com. ©2019 DRUM WORKSHOP, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Volume 44 • Number 6 Cover photo by CONTENTS Galbraith/IconicPix/AtlasIcons.com 23 1970: THE YEAR IN DRUMMING As the turbulent ’60s faded in the rearview, new trends in music—jazz-fusion, sing- er-songwriter, funk-rock, heavy metal, blues-rock—began to form and capture listeners’ imaginations. This month we examine the work of fi ve drummers who were at the cutting edge of their respective corners of the musical universe, at the beginning of what many consider the greatest decade in music ever. 24 BLACK SABBATH’S BILL WARD 38 FUSION STAR LENNY WHITE 42 STUDIO AND TOURING GREAT JIM GORDON 46 PARLIAMENT-FUNKADELIC’S TIKI FULWOOD 48 WEST COAST POP JOURNEYMAN JOHNY BARBATA 8 THE PRETENDERS’ MARTIN CHAMBERS 10 METHOD BODY’S JOHN NIEKRASZ 14 UP & COMING: SLEATER-KINNEY’S 52 ALEX RÜDINGER 60 WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT… ANGIE BOYLAN The heavy-music phenom and YouTube WARREN STORM? Brooklyn indie band Freezing Cold star tours the U.S. -

Secondary Markets a Broad View of the Titles Many of Radio's Key Top 40 Stations Added to Their "Playlists" Last Week

New Additions To Radio Pia ylists Secondary Markets A broad view of the titles many of radio's key Top 40 stations added to their "Playlists" last week. WBBQ-Augusta, Ga. WKEY-Wichita, Kansas Another Day-Paul McCartney-Apple L. A. Goodbye-Ides Of March-WB Indian Reservation-Raiders-Columbia Sit Yourself Down-Stephen Stills-Atlantic Get In Over My Head-Badge--Exhibit Bad Times, Good Times-Book Of Matches- Going Going Gone-Storm-MGM 20 Century Fox Bo Weevil-Shocking Blue-Colossus WCLO-Columbus, Ohio Paradox-Lancewing-Mainstream Hot Pants-Salvage-Odax Put Your Hand In The Hand-Ocean-Kama WLOF-Orlando, Fla. Sutra Blue Money-Van Morrison-Warner Bros. The World Is Gonna Be Better-Friendship- Oye Como Va-Santana-Columbia Big Tree Hook And Ladder-Nancy Sinatra-Reprise Timothy-Buoys-Scepter Angel Baby-Dusk-Bell Pushbike-Mixtures-Sire Pick: Pass Me By-Hello People-Mediarts Tongue In Cheek-Sugarloaf-Liberty WLAV-Grand Rapids, Mich. Another/Oh Woman-Paul McCartney-Apple Another Day-Paul McCartney --Apple 18-Alice Cooper-WB Put Your Hand In The Hand--Ocean-Kama HIS WIFE'S PRODUCER-Photographed during a break at Abbey Road KIOA-Des Moines, Iowa Sutra Each Day Is A Lifetime-David Ruffin-Motown Studios in London at the current Ronnie Spector (former lead singer of the Love, Lines-Fifth Dimension-Bell All I Franklin-Atlantic Ronettes and Phil's wife) sessions are from left to right, Joe Marchini (Apple Timothy-Buoys-Scepter You're Need-Aretha No Love At All-B. J. Thomas-Scepter rep.) George Harrison, Ronnie Spector, Phil Spector (producer), Mal Evans Another Day-Paul McCartney-Apple (Apple rep.) and Klaus Voorman (bassist). -

Ftg01:1 Ixtos

Young Karen intro Bros. Warner London. Limited, Records Island by Licensed $0 ofiotr. & IxtoS ftG01:105 I I0 I 17, April CENTS FIVE TWENTY j971 9 No. 15 Volume 2 -- - RPM 17/4/71 RCA/Ampex not in SRL MCA adopts MAPL Irish Rovers set for Toront Sound Recording Licensing Ltd. "We are not now and never have On ret (SRL), subject of much trade been a member of the Sound Re- logo for identification Ontario/BC tours additic press lately, have suffered a cording Licences Limited. Be- televi: slight setback with the with- cause we are a member of the Allan Matthews, national pro- Decca recording unit, The Irish end up drawal of RCA from its ranks CRMA many people have assumed motion manager MCA Records, Rovers, signed in for a return dates and a statement of non -alignment we were in SRL which has re- reports that MCA (Canada) have engagement at Windsor's Club (28); F from Ampex of Canada Ltd. sulted in a great deal of con- adopted the use of RPM Weekly's Top Hat, April 5th, the day their School troversy. We trust this message MAPL logo for use on all future first half hour CBC-TV network in Veri There has been no official state - will clear up any misunderstand- Canadian recordings. show flashes across the nation. from RCA's Vice -President Bob ing that exists." After they complete their five day May da Cook, other than to confirm that The MAPL logo was created Senior RCA has withdrawn from SRL. solely for use as a programmer stay at the Windsor club they SRL was formed in 1969 by the will spend several days in Toronto Commu It is also understood that George assist and was designed for use (2); tip Harrison is no longer the presi- major record companies. -

THE SEVEN DEATHS of EVELYN HARDCASTLE to My Parents, Who Gave Me Everything and Asked for Nothing

THE SEVEN DEATHS OF EVELYN HARDCASTLE To my parents, who gave me everything and asked for nothing. My sister, first and fiercest of my readers from the bumblebees onwards. And my wife, whose love, encouragement, and reminders to look up from my keyboard once in a while, made this book so much more than I thought it could be. CONTENTS One: Day One Two Three Four Five Six Seven Eight Nine: Day Two Ten: Day Three Eleven: Day Four Twelve Thirteen: Day Two (continued) Fourteen: Day Four (continued) Fifteen Sixteen Seventeen Eighteen Nineteen Twenty Twenty-One: Day Two (continued) Twenty-Two: Day Five Twenty-Three Twenty-Four Twenty-Five Twenty-Six Twenty-Seven: Day Two (continued) Twenty-Eight: Day Five (continued) Twenty-Nine Thirty Thirty-One Thirty-Two: Day Six Thirty-Three: Day Two (continued) Thirty-Four: Day Six (continued) Thirty-Five Thirty-Six Thirty-Seven Thirty-Eight Thirty-Nine: Day Two (continued) Forty: Day Six (continued) Forty-One Forty-Two: Day Two (continued) Forty-Three: Day Seven Forty-Four Forty-Five Forty-Six Forty-Seven Forty-Eight Forty-Nine Fifty Fifty-One Fifty-Two: Day Three (continued) Fifty-Three: Day Eight Fifty-Four Fifty-Five Fifty-Six Fifty-Seven: Day Two (continued) Fifty-Eight: Day Eight (continued) Fifty-Nine Sixty Acknowledgements A Note on the Author You are cordially invited to Blackheath House for The Masquerade Introducing your hosts, the Hardcastle family Lord Peter Hardcastle & Lady Helena Hardcastle & Their son, Michael Hardcastle Their daughter, Evelyn Hardcastle -Notable Guests- Edward Dance, Christopher