A Discourse of Legitimacy Critiquing the Culture Agenda in Finnish Public Broadcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio and Television Correspondents' Galleries

RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES* SENATE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–325, 224–6421 Director.—Michael Mastrian Deputy Director.—Jane Ruyle Senior Media Coordinator.—Michael Lawrence Media Coordinator.—Sara Robertson HOUSE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–321, 225–5214 Director.—Tina Tate Deputy Director.—Olga Ramirez Kornacki Assistant for Administrative Operations.—Gail Davis Assistant for Technical Operations.—Andy Elias Assistants: Gerald Rupert, Kimberly Oates EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES Joe Johns, NBC News, Chair Jerry Bodlander, Associated Press Radio Bob Fuss, CBS News Edward O’Keefe, ABC News Dave McConnell, WTOP Radio Richard Tillery, The Washington Bureau David Wellna, NPR News RULES GOVERNING RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES 1. Persons desiring admission to the Radio and Television Galleries of Congress shall make application to the Speaker, as required by Rule 34 of the House of Representatives, as amended, and to the Committee on Rules and Administration of the Senate, as required by Rule 33, as amended, for the regulation of Senate wing of the Capitol. Applicants shall state in writing the names of all radio stations, television stations, systems, or news-gathering organizations by which they are employed and what other occupation or employment they may have, if any. Applicants shall further declare that they are not engaged in the prosecution of claims or the promotion of legislation pending before Congress, the Departments, or the independent agencies, and that they will not become so employed without resigning from the galleries. They shall further declare that they are not employed in any legislative or executive department or independent agency of the Government, or by any foreign government or representative thereof; that they are not engaged in any lobbying activities; that they *Information is based on data furnished and edited by each respective gallery. -

European Public Service Broadcasting Online

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI, COMMUNICATIONS RESEARCH CENTRE (CRC) European Public Service Broadcasting Online Services and Regulation JockumHildén,M.Soc.Sci. 30November2013 ThisstudyiscommissionedbytheFinnishBroadcastingCompanyǡYle.Theresearch wascarriedoutfromAugusttoNovember2013. Table of Contents PublicServiceBroadcasters.......................................................................................1 ListofAbbreviations.....................................................................................................3 Foreword..........................................................................................................................4 Executivesummary.......................................................................................................5 ͳIntroduction...............................................................................................................11 ʹPre-evaluationofnewservices.............................................................................15 2.1TheCommission’sexantetest...................................................................................16 2.2Legalbasisofthepublicvaluetest...........................................................................18 2.3Institutionalresponsibility.........................................................................................24 2.4Themarketimpactassessment.................................................................................31 2.5Thequestionofnewservices.....................................................................................36 -

The Public Service Broadcasting Culture

The Series Published by the European Audiovisual Observatory What can you IRIS Special is a series of publications from the European Audiovisual Observatory that provides you comprehensive factual information coupled with in-depth analysis. The expect from themes chosen for IRIS Special are all topical issues in media law, which we explore for IRIS Special in you from a legal perspective. IRIS Special’s approach to its content is tri-dimensional, with overlap in some cases, depending on the theme. terms of content? It offers: 1. a detailed survey of relevant national legislation to facilitate comparison of the legal position in different countries, for example IRIS Special: Broadcasters’ Obligations to Invest in Cinematographic Production describes the rules applied by 34 European states; 2. identifi cation and analysis of highly relevant issues, covering legal developments and trends as well as suggested solutions: for example IRIS Special, Audiovisual Media Services without Frontiers – Implementing the Rules offers a forward-looking analysis that will continue to be relevant long after the adoption of the EC Directive; 3. an outline of the European or international legal context infl uencing the national legislation, for example IRIS Special: To Have or Not to Have – Must-carry Rules explains the European model and compares it with the American approach. What is the source Every edition of IRIS Special is produced by the European Audiovisual Observatory’s legal information department in cooperation with its partner organisations and an extensive The Public of the IRIS Special network of experts in media law. The themes are either discussed at invitation-only expertise? workshops or tackled by selected guest authors. -

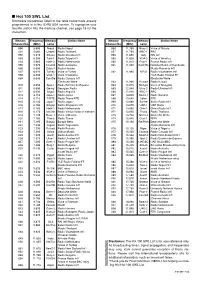

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

27.1. at 20:00 Helsinki Music Centre We Welcome Conrad Tao Sakari

27.1. at 20:00 Helsinki Music Centre We welcome Conrad Tao Sakari Oramo conductor Conrad Tao piano Lotta Emanuelsson presenter Andrew Norman: Suspend, a fantasy for piano and orchestra 1 Béla Bartók: Divertimento for String Orchestra 1. Allegro non troppo 2. Molto adagio 3. Allegro assai Conrad Tao – “shaping the future of classical music” “Excess. I find it to be for me like the four, and performed Mozart’s A-major pia- most vividly human aspect of musical no concerto at the age of eight. He was performance,” says pianist Conrad Tao (b. nine when the family moved to New York, 1994). And “excess” really is a good word where he nowadays lives. Beginning his to describe his superb technique, his pro- piano studies in Chicago, he continued at found interpretations and his emphasis on the Juilliard School, New York, and atten- the human aspect in general. ded Yale for composition. Tao has a wide repertoire ranging from Tao has had a manager ever since Bach to the music of today. He has also he was twelve. As a youngster, he also won recognition as a composer, and one learnt the violin, and several times in who, he says, views his keyboard perfor- 2008/2009 played both the E-minor vio- mances through the eyes of a composer. lin concerto and the first piano concerto His many talents and his ability to cross by Mendelssohn at one and the same con- traditional borders have indeed made him cert, but he soon gave up the violin. a notable influencer and a model for ot- Despite having all the hallmarks of a hers. -

Eurodoc Executive Meeting – an Exclusive Meeting Platform for Documentary Executives and Commissioning Editors

EURODOC EXECUTIVE MEETING – AN EXCLUSIVE MEETING PLATFORM FOR DOCUMENTARY EXECUTIVES AND COMMISSIONING EDITORS Tuesday, 2nd of October 2018 Geneva, Eurodoc for Executives CHANGE IN PUBLIC SERVICE PLATFORM CURATING – MORE THAN ALGORHYTHM ? With Jeroen Depraetere, Head of Television and Future, EBU Curation and algorithms as ways of enhancing our service are definitely something public service should take up (have taken up…), but it seems to be developing very slowly almost everywhere. The news of the planned "Alliance" of France Televisions, ZDF and RAI, or the planned joint streaming service of BBC, Channel4 and ITV make it very clear that also the European public service media have understood that the media landscape will be dominated by big international or global players. The survival for documentary programs and smaller players in this landscape will require co-operation and high quality of not only the content but also the service. We may find ourselves having to create and defend a position not within one national public service broadcaster but a conglomerate of many. LUNCH for Executives only 2.30 PM – 5 PM WELCOME & INTRODUCTION INPUT by Jeroen Depraetere, Head of Television and Future, European Broadcasting Union EBU, Geneva, introducing to the « Alliance » of France Télévision, ZDF and RAI and other public initiatives followed by a discussion INTERNATIONAL CASE STUDYS by our participants from the different services such as ARTE, SRF, HBO etc. THE EURODOC EXECUTIVE’S MEETING Since 2013, Eurodoc also offers an exclusive opportunity to meet amongst Documentary Executives and Commissioning Editors only. This exclusive meeting always takes place on the first day of the Eurodoc session and is curated by Anita Hugi (SRF) for Eurodoc. -

Preserving TV & Broadcast Archives

PreservingPreserving TVTV && BroadcastBroadcast ArchivesArchives JuneJune 20022002 AdrianAdrian WilliamsWilliams SizeSize ofof thethe ArchiveArchive • The BBC has one of the largest multi-media archives in the world • 1.75 million items of film and videotape • 800,000 radio recordings • 3 million photographs • 1.2 million commercial recordings • 4 million items of sheet music • 22.5 million newspaper cuttings • 600,000 document files • 20,000 rolls of microfilm • 500,000 phonetic pronunciations UsageUsage ofof FormatsFormats 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2” Quad Videotape 1” C Format Videotape U-MATIC Videotape BETA Reversal Film Eastman & B/W Film Acetate Magnetic Sound Track TV Progs Sound - Shellac & Vinyl Discs Preservation of the Archives – total estimated spend £60M Formats at Film Sound 1” C U-Matic Reversal Eastman & 2” Quad B/W Film Risk Track Film (Ekta) Phases 1 & 2 Phases 1 & Phase 1 Phase 1 Vinyl BetaSP £1.4M 2 £1.17M £390K Sept 1998- £1.5M Sept Sept Oct 99 Sept 1998- 1998- 1998- Completed! Dec99 Dec99 Dec99 Interim: Jan 2000 £120K £260K £20K £7M £1.8M 3-yr Funding from May 2000 £6M £2M £2M Total Investment £6M £7M £16M £5M £3M £2M £9M £10M Preservation of the Archives – total estimated spend £60M Formats at Film Sound 1” C U-Matic Reversal Eastman & 2” Quad B/W Film Risk Track Film (Ekta) Vinyl BetaSP Project completed by Mar 2003 From £1M £3M April 2003 £9M £1.3M £9M From April 2006 £10M Total Investment £6M £7M £16M £5M £3M £2M £9M £10M PREPARATION & RESEARCH Offline editing Internet ARCHIVE MANIPU- RE-USE LATION CAPTURE IDEA -

Mapping Digital Media:Finland

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: FINLAND Mapping Digital Media: Finland A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Sampsa Saikkonen and Paula Häkämies EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Stewart Chisholm, associate director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 5 January 2014 Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 11 Economic Indicators ......................................................................................................................... 13 1. Media Consumption: Th e Digital Factor .................................................................................. -

Selection Spring/Summer 2018 Ars E Y

ars e y 25 Selection Spring/Summer 2018 ars e y Selection Spring/Summer 2018 25 .. 2 .. ars e y Selection Spring/Summer 2018 25 Highlight — Preschool KiKANiNCHEN Animation 26 x 1’ + 10 x 3’ Preschool Rating hit KiKANiNCHEN is a successful, multimedia preschool programme on KiKA, the public service children’s channel run by ARD / ZDF in Germany. It is tailored to the development and needs of our youngest newcomers to media. The darling of every child is Kikaninchen, an animated 3D figure that accompanies the children throughout the program. Its grown-up friends Anni, Christian and Jule, who have great ideas, know stories and provide motivation, are always by the rabbit’s side. The popular bite-sized adventures and stories have been specifically developed for children aged between three and six, and take place in a 2D world of paper snippets. These appealing aesthetics for children as well as the catchy songs provide a high level of audiovisual recognition value. KiKANiNCHEN is a trusted brand and also well-known for outstanding merchandising products in Germany. As seen on: KiKA Produced by: Studio.TV.Film Web: www.kikaninchen.de Preschool School of Roars Animation 52 x 7’ Preschool Rating hit Multiple language versions available School of Roars … Where monsters go to growl and grow! Going to school for the first time is one of the biggest things you’ll do in your life. You’re away from home, fitting in with routines and learning so many new things … whilst also getting along with a class full of new friends. -

RTÉ's Saorview Wholesale Access Reference Offer

RAIDIÓ TEILIFÍS ÉIREANN WHOLESALE ACCESS REFERENCE OFFER UTV IRELAND LIMITED MARKET B – DTT MULTIPLEXING SERVICES AGREEMENT SUBJECT TO CONTRACT/CONTRACT DENIED The following document is RTÉ’s “wholesale access reference offer” (“WARO”) published pursuant to ComReg’s Decision Notice D11/13. This document does not constitute an offer capable of acceptance or a template contract intended to act as a first draft for negotiations. It is a reference document so that third parties seeking wholesale access to DTT multiplexing services (“Market B”) can gain an overview and understanding of the form of agreement they will be required to enter. It is RTÉ’s intention that the majority of its wholesale broadcasting services agreements would be in substantially the same format as this reference document. However individual negotiations may lead to amendments for particular applicants on a case by case basis. For example agreements requiring the roll out of additional network infrastructure or concerns RTÉ may have in relation to the credit worthiness of a particular client may require the satisfaction of certain specific pre-conditions prior to entering into the agreement or the inclusion of any number of provisions within the agreement or its Appendices. The services covered by this WARO are strictly limited to those services necessary to comply with ComReg’s Decision Notice D11/13. This document must be read with the relevant RTÉ Saorview Wholesale Access Reference Offer Appendix B document published on the RTÉ.ie website. RTÉ SAORVIEW – Wholesale Access Reference Offer Page 1 of 61 March 2019 CHANGE CONTROL First published: 26 November 2013 Revised: 4th February, 2014:- Revised: 2nd March, 2014:- Revised: 30th April, 2015:- Revised: 23rd March 2017:- Page 34 symbol changes from Ú to Ω Revised Jan 2019: - Update for the 5 year model starting 1st April 2019 RTÉ SAORVIEW – Wholesale Access Reference Offer Page 2 of 61 March 2019 TABLE OF CONTENT 1 INTERPRETATION................................................................................................................. -

Digital Radio Summit 2020 Event Summary

DIGITAL RADIO SUMMIT 2020 EVENT SUMMARY EBU, Geneva – 12 February 2020 Presentations and videos: https://tech.ebu.ch/drs2020 Disclaimer: This report is intended as a quick overview of the event. Before quoting any of the speakers we recommend that you refer to the original presentation and check with the speakers themselves. KEYNOTE SESSION / A BROADER VIEW Welcome to the Digital Radio Summit The future of in car listening: Antonio Arcidiacono (EBU) opportunities and choices Eleanor Van Heyningen, Asha Knight (BBC) Radio is one area where public service media lead the market. Live Roughly a third of all radio listening is in the car, representing 13% of all content remains a strong differentiator – nothing will replace it. And the time spent with BBC by UK audiences. Since 2012 there’s been a 17% ability to deliver news as it happens in real time is the other big growth in UK in-car radio listening, but there’s still no audio at all 50% of differentiator. the time, so there’s a big opportunity. There are DAB radios in 95% of new cars, so the preconditions are good. But there are three main drivers for We are evolving towards a future that will include broadcast for live change: young people tend to use a tethered device in the car; the content and events; unicast for personalized, one-to-one experiences; and connected car is here; and Big Tech wants to play a bigger role. multicast, using local storage in receiver devices, for push content. The smartphone will be a unifying device that knits together the various BBC sees Radioplayer, which it part-owns, as the best route to protecting different platforms and listening contexts. -

Drama Directory 2014

2014 UPDATE CONTENTS Acknowlegements ..................................................... 2 Latvia .......................................................................... 122 Introduction ................................................................. 3 Lithuania ................................................................... 125 Luxembourg ............................................................ 131 Austria .......................................................................... 4 Malta .......................................................................... 133 Belgium ...................................................................... 10 Netherlands ............................................................. 135 Bulgaria ....................................................................... 21 Norway ..................................................................... 145 Cyprus ......................................................................... 26 Poland ........................................................................ 151 Czech Republic ......................................................... 31 Portugal .................................................................... 157 Denmark .................................................................... 36 Romania ................................................................... 160 Estonia ........................................................................ 42 Slovakia ...................................................................