Old, Educated, and Politically Diverse: the Audience of Public Service News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I N H a L T S V E R Z E I C H N

SWR BETEILIGUNGSBERICHT 2018 Beteiligungsübersicht 2018 Südwestrundfunk 100% Tochtergesellschaften Beteiligungsgesellschaften ARD/ZDF Beteiligungen SWR Stiftungen 33,33% Schwetzinger SWR Festspiele 49,00% MFG Medien- und Filmgesellschaft 25,00% Verwertungsgesellschaft der Experimentalstudio des SWR e.V. gGmbH, Schwetzingen BaWü mbH, Stuttgart Film- u. Fernsehproduzenten mbH Baden-Baden 45,00% Digital Radio Südwest GmbH 14,60% ARD/ZDF-Medienakademie Stiftung Stuttgart gGmbH, Nürnberg Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv Frankfurt 16,67% Bavaria Film GmbH 11,43% IRT Institut für Rundfunk-Technik Stiftung München GmbH, München Hans-Bausch-Media-Preis 11,11% ARD-Werbung SALES & SERV. GmbH 11,11% Degeto Film GmbH Frankfurt München 0,88% AGF Videoforschung GmbH 8,38% ARTE Deutschland TV GmbH Frankfurt Baden-Baden Mitglied Haus des Dokumentarfilms 5,56% SportA Sportrechte- u. Marketing- Europ. Medienforum Stgt. e. V. agentur GmbH, München Stammkapital der Vereinsbeiträge 0,98% AGF Videoforschung GmbH Frankfurt Finanzverwaltung, Controlling, Steuerung und weitere Dienstleistungen durch die SWR Media Services GmbH SWR Media Services GmbH Stammdaten I. Name III. Rechtsform SWR Media Services GmbH GmbH Sitz Stuttgart IV. Stammkapital in Euro 3.100.000 II. Anschrift V. Unternehmenszweck Standort Stuttgart - die Produktion und der Vertrieb von Rundfunk- Straße Neckarstraße 230 sendungen, die Entwicklung, Produktion und PLZ 70190 Vermarktung von Werbeeinschaltungen, Ort Stuttgart - Onlineverwertungen, Telefon (07 11) 9 29 - 0 - die Beschaffung, Produktion und Verwertung -

Contribution of Public Service Media in Promoting Social Cohesion

COUNCIL CONSEIL OF EUROPE DE L’EUROPE Contribution of public service media in promoting social cohesion and integrating all communities and generations Implementation of Committee of Ministers Recommendation Rec (97) 21 on media and the promotion of a culture of tolerance Group of Specialists on Public Service Media in the Information Society (MC-S-PSM) H/Inf (2009) 5 Contribution of public service media in promoting social cohesion and integrating all communities and generations Implementation of Committee of Ministers’ Recommendation Rec (97) 21 on media and the promotion of a culture of tolerance Report prepared by the Group of Specialists on Public Service Media in the Information Society (MC-S-PSM), November 2008 Directorate General of Human Rights and Legal Affairs Council of Europe Strasbourg, June 2009 Édition française : La contribution des médias de service public à la promotion de la cohésion sociale et a l’intégration de toutes les communautés et générations Directorate General of Human Rights and Legal Affairs Council of Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex http://www.coe.int/ © Council of Europe 2009 Printed at the Council of Europe Contents Executive summary . .5 Introduction . .5 Key developments . .6 Workforce . 6 Requirements . .11 Content and services . 13 Conclusions, recommendations and proposals for further action . 18 Conclusions . .18 Recommendations and proposals for further action . .20 Appendix A. Recommendation No. R (97) 21 . 22 Recommendation No. R (97) 21 on Appendix to Recommendation No. R the media and the promotion of a (97) 21 . .22 culture of tolerance . .22 Appendix B. Questionnaire on public service media and the promotion of a culture of tolerance . -

Radio and Television Correspondents' Galleries

RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES* SENATE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–325, 224–6421 Director.—Michael Mastrian Deputy Director.—Jane Ruyle Senior Media Coordinator.—Michael Lawrence Media Coordinator.—Sara Robertson HOUSE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–321, 225–5214 Director.—Tina Tate Deputy Director.—Olga Ramirez Kornacki Assistant for Administrative Operations.—Gail Davis Assistant for Technical Operations.—Andy Elias Assistants: Gerald Rupert, Kimberly Oates EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES Joe Johns, NBC News, Chair Jerry Bodlander, Associated Press Radio Bob Fuss, CBS News Edward O’Keefe, ABC News Dave McConnell, WTOP Radio Richard Tillery, The Washington Bureau David Wellna, NPR News RULES GOVERNING RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES 1. Persons desiring admission to the Radio and Television Galleries of Congress shall make application to the Speaker, as required by Rule 34 of the House of Representatives, as amended, and to the Committee on Rules and Administration of the Senate, as required by Rule 33, as amended, for the regulation of Senate wing of the Capitol. Applicants shall state in writing the names of all radio stations, television stations, systems, or news-gathering organizations by which they are employed and what other occupation or employment they may have, if any. Applicants shall further declare that they are not engaged in the prosecution of claims or the promotion of legislation pending before Congress, the Departments, or the independent agencies, and that they will not become so employed without resigning from the galleries. They shall further declare that they are not employed in any legislative or executive department or independent agency of the Government, or by any foreign government or representative thereof; that they are not engaged in any lobbying activities; that they *Information is based on data furnished and edited by each respective gallery. -

An Film Partners, Zdf / Arte, Mam, Cnc, Medienboard Berlin Brandenburg Comme Des Cinemas, Nagoya Broadcasting Network and Twenty Twenty Vision

COMME DES CINEMAS, NAGOYA BROADCASTING NETWORK AND TWENTY TWENTY VISION AN FILM PARTNERS, ZDF / ARTE, MAM, CNC, MEDIENBOARD BERLIN BRANDENBURG COMME DES CINEMAS, NAGOYA BROADCASTING NETWORK AND TWENTY TWENTY VISION SYNOPSIS Sentaro runs a small bakery that serves dorayakis - pastries filled with sweet red bean paste(“an”) . When an old lady, Tokue, offers to help in the kitchen he reluctantly accepts. But Tokue proves to have magic in her hands when it comes to making “an”. Thanks to her secret recipe, the little business soon flourishes… And with time, Sentaro and Tokue will open their hearts to reveal old wounds. 113 minutes / Color / 2.35 / HD / 5.1 / 2015 DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT Cherry trees in full bloom remind us of death. I do not know of any other tree whose flowers blossom in such a spectacular way, only to have their petals scatter just as suddenly. Is this the reason behind our fascination for blossoming cherry trees? Is this why we are compelled to see a reflection of our own lives in them? Sentaro, Tokue and Wakana meet when the cherry trees are in full bloom. The trajectories of these three people are very different. And yet, their souls cross paths and meet one another in the same landscapes. Our society is not always predisposed to letting our dreams become reality. Sometimes, it swallows up our hopes. After learning that Tokue is infected with leprosy, the story pulls us into a quest for the very essence of what makes us human. As a director, I have the honour and pleasure of exploring different lives through cinema, as is the case with this film. -

Facts and Figures 2020 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020

Facts and Figures 2020 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020 Facts about ZDF ZDF (Zweites Deutsches Fern German channels PHOENIX and sehen) is Germany’s national KiKA, and the European chan public television. It is run as an nels 3sat and ARTE. independent nonprofit corpo ration under the authority of The corporation has a permanent the Länder, the sixteen states staff of 3,600 plus a similar number that constitute the Federal of freelancers. Since March 2012, Republic of Germany. ZDF has been headed by Direc torGeneral Thomas Bellut. He The nationwide channel ZDF was elected by the 60member has been broadcasting since governing body, the ZDF Tele 1st April 1963 and remains one vision Council, which represents of the country’s leading sources the interests of the general pub of information. Today, ZDF lic. Part of its role is to establish also operates the two thematic and monitor programme stand channels ZDFneo and ZDFinfo. ards. Responsibility for corporate In partnership with other pub guide lines and budget control lic media, ZDF jointly operates lies with the 14member ZDF the internetonly offer funk, the Administrative Council. ZDF’s head office in Mainz near Frankfurt on the Main with its studio complex including the digital news studio and facilities for live events. Seite 2 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020 Facts about ZDF ZDF is based in Mainz, but also ZDF offers fullrange generalist maintains permanent bureaus in programming with a mix of the 16 Länder capitals as well information, education, arts, as special editorial and production entertainment and sports. -

Increased Transparency and Efficiency in Public Service Broadcasting

Competition Policy Newsletter Increased transparency and efficiency in public service AID STATE broadcasting. Recent cases in Spain and Germany (1) Pedro Dias and Alexandra Antoniadis Introduction The annual contribution granted to RTVE was made dependent upon the adoption of measures Since the adoption of the Broadcasting Communi- to increase efficiency. The Spanish authorities cation in 200, the Commission followed a struc- commissioned a study on the financial situation tured and consistent approach in dealing with of RTVE which revealed that the — at the time numerous complaints lodged against the financ- — existing workforce exceeded what was neces- ing of public service broadcasters in Europe. It sary for the fulfilment of the public service tasks. reviewed in particular the existing financing Agreement could be reached between the Span- regimes and discussed with Member States meas- ish authorities, RTVE and trade unions on a sig- ures to ensure full compliance with the EU State nificant reduction of the workforce through early aid rules. The experience has been positive: Sev- retirement measures. The Spanish State decided to eral Member States have either already changed or finance these measures, thus alleviating RTVE of committed themselves to changing the financing costs it would normally have to bear. The savings rules for public service broadcasters to implement in terms of labour costs and consequently pub- fundamental principles of transparency and pro- lic service costs of RTVE exceeded the financial portionality (2). burden of the Spanish State due to the financing of the workforce reduction measures. The Com- The present article reviews the two most recent mission approved the aid under Article 86 (2) EC decisions in this field which are examples of Treaty, also considering the overall reduction of increased efficiency and transparency in public State aid to the public service broadcaster (). -

Towards an Aesthetic of the Migrant Self — the Film Le Clandestin by José Zeka Laplaine

MARIE–HÉLÈNE GUTBERLET ⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯ Towards an Aesthetic of the Migrant Self — The Film Le Clandestin by José Zeka Laplaine A BSTRACT: The representation of migrant arrivals in Europe is at the centre of this investigation of Zeka Laplaine’s short film Le Clandestin (1996). Placing the short film in the context of the African cinematographic traditions of earlier, more conventional, migrant narratives, the essay shows that the associative structure and the postmodern use of irony and magical realism in this short film question both our sense of familiarity and the promise of effortless transcultural communication. 1 OST FILMS (cinema and television productions) dealing with African migration, especially migration to Europe, are produced M and realized by European film and broadcasting companies. They reflect a specific attitude towards individuals and their situation and towards the issue of foreign presence on European soil. The portrayal and production of the African migrant in European media represents a complex field of poli- tically, socially, racially, and aesthetically relevant influences that would need to be analysed specifically. Awareness of these issues has spread beyond the academic field: everybody is more or less familiar with the images of African migrants, with the unease, the exaggerations, humiliations, and transformations taking place in the production of these images, and has learned to view against the grain and sometimes see behind the obvious. Another concern underlies the present essay: are there other ways of expressing and showing the arrival of © Transcultural Modernities: Narrating Africa in Europe, ed. Elisabeth Bekers, Sissy Helff & Daniela Merolla (Matatu 36; Amsterdam & New York NY: Editions Rodopi, 2009). -

European Public Service Broadcasting Online

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI, COMMUNICATIONS RESEARCH CENTRE (CRC) European Public Service Broadcasting Online Services and Regulation JockumHildén,M.Soc.Sci. 30November2013 ThisstudyiscommissionedbytheFinnishBroadcastingCompanyǡYle.Theresearch wascarriedoutfromAugusttoNovember2013. Table of Contents PublicServiceBroadcasters.......................................................................................1 ListofAbbreviations.....................................................................................................3 Foreword..........................................................................................................................4 Executivesummary.......................................................................................................5 ͳIntroduction...............................................................................................................11 ʹPre-evaluationofnewservices.............................................................................15 2.1TheCommission’sexantetest...................................................................................16 2.2Legalbasisofthepublicvaluetest...........................................................................18 2.3Institutionalresponsibility.........................................................................................24 2.4Themarketimpactassessment.................................................................................31 2.5Thequestionofnewservices.....................................................................................36 -

The Public Service Broadcasting Culture

The Series Published by the European Audiovisual Observatory What can you IRIS Special is a series of publications from the European Audiovisual Observatory that provides you comprehensive factual information coupled with in-depth analysis. The expect from themes chosen for IRIS Special are all topical issues in media law, which we explore for IRIS Special in you from a legal perspective. IRIS Special’s approach to its content is tri-dimensional, with overlap in some cases, depending on the theme. terms of content? It offers: 1. a detailed survey of relevant national legislation to facilitate comparison of the legal position in different countries, for example IRIS Special: Broadcasters’ Obligations to Invest in Cinematographic Production describes the rules applied by 34 European states; 2. identifi cation and analysis of highly relevant issues, covering legal developments and trends as well as suggested solutions: for example IRIS Special, Audiovisual Media Services without Frontiers – Implementing the Rules offers a forward-looking analysis that will continue to be relevant long after the adoption of the EC Directive; 3. an outline of the European or international legal context infl uencing the national legislation, for example IRIS Special: To Have or Not to Have – Must-carry Rules explains the European model and compares it with the American approach. What is the source Every edition of IRIS Special is produced by the European Audiovisual Observatory’s legal information department in cooperation with its partner organisations and an extensive The Public of the IRIS Special network of experts in media law. The themes are either discussed at invitation-only expertise? workshops or tackled by selected guest authors. -

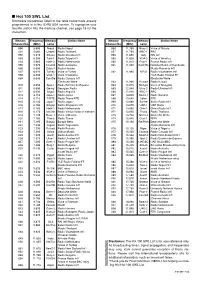

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

27.1. at 20:00 Helsinki Music Centre We Welcome Conrad Tao Sakari

27.1. at 20:00 Helsinki Music Centre We welcome Conrad Tao Sakari Oramo conductor Conrad Tao piano Lotta Emanuelsson presenter Andrew Norman: Suspend, a fantasy for piano and orchestra 1 Béla Bartók: Divertimento for String Orchestra 1. Allegro non troppo 2. Molto adagio 3. Allegro assai Conrad Tao – “shaping the future of classical music” “Excess. I find it to be for me like the four, and performed Mozart’s A-major pia- most vividly human aspect of musical no concerto at the age of eight. He was performance,” says pianist Conrad Tao (b. nine when the family moved to New York, 1994). And “excess” really is a good word where he nowadays lives. Beginning his to describe his superb technique, his pro- piano studies in Chicago, he continued at found interpretations and his emphasis on the Juilliard School, New York, and atten- the human aspect in general. ded Yale for composition. Tao has a wide repertoire ranging from Tao has had a manager ever since Bach to the music of today. He has also he was twelve. As a youngster, he also won recognition as a composer, and one learnt the violin, and several times in who, he says, views his keyboard perfor- 2008/2009 played both the E-minor vio- mances through the eyes of a composer. lin concerto and the first piano concerto His many talents and his ability to cross by Mendelssohn at one and the same con- traditional borders have indeed made him cert, but he soon gave up the violin. a notable influencer and a model for ot- Despite having all the hallmarks of a hers. -

Mediaset España Sets New Historical Record with 18,5 Million Unique Users in May

Madrid, 12th June, 2013 According to the monthly report of OJD MEDIASET ESPAÑA SETS NEW HISTORICAL RECORD WITH 18,5 MILLION UNIQUE USERS IN MAY • In one year, the media group has increased its traffic by 11.2% compared to May 2012. Telecinco.es has grown by 9.2%, and Cuatro.com 20.6% and Divinity.es has registered an excellent growth of 44.5% • Exceeding Grupo RTVE, by almost 1.8 million monthly unique users • Telecinco.es the third most watched national media in the overall ranking of digital media audited by OJD, surpassed only by Marca.com and Elmundo.es • In addition, Telecinco is a leading in social share in May and became the first channel to exceed 4 million comments a month Once again, Mediaset España sets new record Internet audience to record 18.5 million unique users in May, the month in which Telecinco.es and Divinity.es have also beaten their own record highs with 15.8 million and 1.5 million unique users, respectively, according to the audited report of OJD. In one year, the audiovisual group preferred by users has increased Internet traffic (monthly unique visitors) by 11.2% compared to May 2012. Per site, the growth was 9.2% for Telecinco.es, Cuatro.com 20.6% and an excellent 44.5% for Divinity.es. Mediaset España continues to be absolute leader in Internet among Spanish television operators, both monthly unique browsers (18,483,679 users) and daily traffic (1,487,468 users), ahead of its nearest competitor (*), RTVE Group, which includes all RTVE and RNE sites - by almost 1.8 million monthly unique browsers and 337 808 unique visitors per day.