Porsche Twin-Cam 6-Cylinder Engine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Porsche Collection Phillip Island Classic PORSCHES GREATEST HITS PLAY AGAIN by Michael Browning

The Formula 1 Porsche displayed an interesting disc brake design and pioneering cooling fan placed horizontally above its air-cooled boxer engine. Dan Gurney won the 1962 GP of France and the Solitude Race. Thereafter the firm withdrew from Grand Prix racing. The Porsche Collection Phillip Island Classic PORSCHES GREATEST HITS PLAY AGAIN By Michael Browning Rouen, France July 8th 1962: It might have been a German car with an American driver, but the big French crowd But that was not the end of Porsche’s 1969 was on its feet applauding as the sleek race glory, for by the end of the year the silver Porsche with Dan Gurney driving 908 had brought the marque its first World took the chequered flag, giving the famous Championship of Makes, with notable wins sports car maker’s new naturally-aspirated at Brands Hatch, the Nurburgring and eight cylinder 1.5 litre F1 car its first Grand Watkins Glen. Prix win in only its fourth start. The Type 550 Spyder, first shown to the public in 1953 with a flat, tubular frame and four-cylinder, four- camshaft engine, opened the era of thoroughbred sports cars at Porsche. In the hands of enthusiastic factory and private sports car drivers and with ongoing development, the 550 Spyder continued to offer competitive advantage until 1957. With this vehicle Hans Hermann won the 1500 cc category of the 3388 km-long Race “Carrera Panamericana” in Mexico 1954. And it was hardly a hollow victory, with The following year, Porsche did it all again, the Porsche a lap clear of such luminaries this time finishing 1st, 2nd, 4th and 5th in as Tony Maggs’ and Jim Clark’s Lotuses, the Targa Florio with its evolutionary 908/03 Graham Hill’s BRM. -

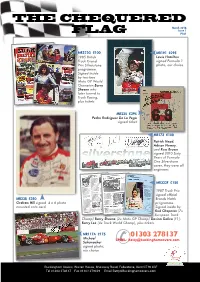

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

Targa Florio Winner in the Porsche 908

Gerhard Mitter – Targa Florio winner in the Porsche 908 Gerhard Mitter was one of the greatest racing drivers Germany has ever produced. A Porsche works driver who took three European Hill Climb Championship titles, he suffered a fatal accident shortly before his planned move to Formula One. In the 1960s, the European Hill Climb Championship was one of the premier competitions in motor sport. The most successful driver of the era was Gerhard Mitter, who had been recruited to the Porsche works team to replace the late Edgar Barth. Mitter emulated Barth in taking three European Hill Climb Championship titles and even surpassed the achievements of his predecessor by winning them in consecutive years. In 1966, 1967 and 1968, he triumphed against rival entries from Ferrari, BMW and Abarth – and successfully fended off his ambitious teammate Rolf Stommelen in the latter two seasons. The cars that took him to these victories were primarily the Porsche 906 Carrera 6 and various versions of the Porsche 910. With his ability to focus all his energy and concentration on a period of a few short minutes, Mitter became one of the most dominant racers in the mountains. In 1969, Mitter was among the drivers who entered into Porsche legend by steering the company to its first ever title in the International Championship for Makes. He went on to record his greatest victory in the May of that year, taking first place at the Targa Florio – part of the World Sportscar Championship – with Udo Schütz in the Porsche 908. Within the large works team, Gerhard Mitter was the first point of contact for the engineering team around Peter Falk. -

STARTERLISTE 1963 DEUTSCHE FORMEL-JUNIOR-MEISTERSCHAFT Nr

STARTERLISTE 1963 DEUTSCHE FORMEL-JUNIOR-MEISTERSCHAFT Nr. Nation Fahrer Bewerber Fahrzeug Team Motor 1 BEL Paul Deetens Belgian Racing Team Cooper T59 Belgian Racing Team BMC 1 GER "Franz Müller" „Franz Müller“ Lola Mk5A Roman Dirschl Ford 1 GER Kurt Ahrens sen. Kurt Ahrens sen. Lotus 27/27-J-25 Kurt Ahrens sen. Ford 1 GER Richard Weber Richard Weber Lotus 18 Richard Weber DKW 1 GER Kurt Ahrens jun. Kurt Ahrens jun. Cooper T67/FJ-2-63 Kurt Ahrens jun. Ford 1 GBR David Prophet David Prophet Brabham BT6/FJ-5-63 David Prophet Ford 1 GBR Peter Arundell Ron Harris - Team Lotus Lotus 27/27-JM-32 Ron Harris Racing Ford 2 BEL Jean-Claude Franck Belgian Racing Team Cooper T67/FJ-5-63 Belgian Racing Team Ford 2 GER Adolf Lang Adolf Lang Cooper T56 Adolf Lang Ford 2 GER Kurt Ahrens jun. Kurt Ahrens jun. Cooper T67/FJ-2-63 Kurt Ahrens jun. Ford 2 GER Ludwig Fischer Ludwig Fischer De Sanctis/0004 Ludwig Fischer Fiat 2 GER Gerhard Mitter Autohaus Mitter Lotus 22/22-J-31 Autohaus Mitter DKW 2 BEL Paul Deetens Belgian Racing Team Cooper T59 Belgian Racing Team BMC 2 GER Bastel Fischer Bastel Fischer Cooper T59/FJ-16-62 Bastel Fischer Ford 2 GBR John Hine Ron Harris - Team Lotus Lotus 27 Ron Harris Racing Ford 3 BEL André Liekens Belgian Racing Team Cooper T52/FJ-7-60 Belgian Racing Team BMC 3 GER Richard Weber Richard Weber Lotus 18 Richard Weber DKW 3 GER Gerhard Mitter Gerhard Mitter Lotus 22/22-J-31 Autohaus Mitter DKW 3 GER Hendrick Fleischmann Karl Schumacher Lotus 18 Karl Schumacher Ford 3 GER Adolf Körber Karl Schumacher Lotus 18 Karl Schumacher -

Where Legends Are Made Ten Particularly Memorable Moments of the Nürburgring

newsroom History Jun 26, 2017 Where Legends Are Made Ten particularly memorable moments of the Nürburgring. It’s both revered and demonized. The Nürburgring elicits strong reactions like no other racetrack in the world. Opened on June 18, 1927, the track will turn ninety in just a few weeks. 1927 Date: July 17, 1927 Winner: Otto Merz Car: Mercedes-Benz Type S Distance: Eighteen laps of 28.265 kilometers (Nordschleife and Südschleife; north and south loops) Winner’s average speed: 101.8 km/h Ferdinand Porsche’s act of will 1936 Date: July 26, 1936 Winner: Bernd Rosemeyer Car: Auto Union Type C Distance: Twenty-two laps of 22.810 km (Nordschleife) Winner’s average speed: 131.6 km/h Page 1 of 5 Wonder car with sixteen cylinders 1956 Date: May 27, 1956 Winners (class S 1.5-liter): Wolfgang Graf Berghe von Trips Umberto Maglioli Car: Porsche 550 A Spyder Distance: Forty-four laps of 22.810 kilometers (Nordschleife) Average speed of overall winners: 129.8 km/h Victory for the ages 1967 Date: May 28, 1967 Winners: Udo Schütz Joe Buzzetta Car: Porsche 910 Distance: Forty-four laps of 22.810 km (Nordschleife) Winners’ average speed: 145.5 km/h One thousand kilometers forever 1970 Date: May 31, 1970 Winners: Vic Elford Kurt Ahrens Car: Porsche 908/03 Spyder Distance: Forty-four laps of 22.810 km (Nordschleife) Winners’ average speed: 165 km/h Porsche wins the championship title 1983 Date: May 28, 1983 (training), May 29, 1983 (race) Winners: Jochen Mass / Jacky Ickx Page 2 of 5 Car: Porsche 956 C Lap record: Stefan Bellof (6:11.13 min.) Distance: -

News 3/09 Porsche Club News 2/09 Porsche Club News 3/09

July 2009 Porsche Club News 3/09 Porsche Club News 2/09 Porsche Club News 3/09 Editorial Dear Porsche Club Presidents, Dear Porsche Club Members, Once again, a number of interesting and • have a driver's seat typical of a sports exciting months have passed by: Anyone car, but also a luxury interior in who has been keeping up with the press premium quality and with segment- recently could easily come to the conclu- specific equipment features. sion that Porsche has lost focus on what’s important – namely its products. Let me But it’s precisely these challenges that assure you that this is not the case and evoke the greatest drive in Porsche engi- that we are working hard at being able to neers. Technical innovations such as us- bring you exciting and aesthetic vehicles ing Porsche Doppelkupplung (PDK), well in the future as well. known in the sports cars, in combination with a start/stop system or the new In times such as these, the positives are Porsche Active Suspension Management all the more important – and the intro- (PASM), adaptive air suspension, have duction of the Panamera most certainly provided answers to these questions – counts as one of these. Although the answers that are not simply a lazy com- vehicle has only just been presented, we promise, but define what is technically have already received extremely encour- possible. And a few weeks ago we were aging feedback worldwide. once again able to demonstrate that the Wolfgang Dürheimer, Member of Panamera is a thoroughbred Porsche, de- the Executive Board for Research There’s nothing better for a development spite the comfort requirements, when I and Development team than when an idea that they have had the unique opportunity to drive the in- spent years developing, refining and troductory lap at the Hockenheimring 24-hour event after an absorbing race. -

The New 911 GT3 – Limits Pushed

01.13 · News Porsche Porsche 01.13 © Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG, 2013 The models featured in this publication are approved for road use in Germany. Some items of equipment are available as extra-cost options only. The availability of models and options may vary from market to market due to News local restrictions and regulations. For information on standard and optional equipment, please consult your Porsche Centre. All information in respect of construction, features, design, performance, dimensions, weight, fuel consumption and running costs is correct at the time of publication. Porsche reserves the right to alter specifications and other product information without prior notice. Colours may differ from those illustrated. Errors and omissions excepted. All text, images and other information in this publication are copyright Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing from Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG. The new 911 GT3 – limits pushed. Porsche, the Porsche Crest, 911, Carrera, PDK, PCM, PSM, PDLS, Spyder, Tequipment, Tiptronic and other marks are registered trademarks of Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG, Porscheplatz 1, 70435 Stuttgart, Germany. 1) The data presented here was recorded using the Euro 5 test procedure (715/2007/EC, 692/2008/EC, 566/2011/EC and ECE-R 101) and the NEDC (New European Driving Cycle). The respective figures were not recorded on individual vehicles and do not constitute part of the offer. This data is provided solely for the purposes of comparison between the respective models. -

September/October 2011 DER GASSER RTR Officers Election for 2012 — Table of Contents — Features

September/October 2011 DER GASSER RTR OFFICERS ELECTION FOR 2012 — Table of Contents — Features Fall is fast approaching and this is a reminder that our election meeting Riesentöter donates to International is coming up in October (date TBA). Our Bylaws provide that a nominating Motor Racing Research Center ..................... 4 committee (consisting of the President and the three most recent Past- Porsche Repeats Again - Wins J.D. Power Presidents who are still members) recommend nominees for each elected and Associates’ APEAL Study for the Seventh Consecutive Year ..............................4 office. Graham Knight, Tom Zaffarano and Brian Minkin recommend: Rennsport Reunion IV Update ........................ 5 President—Joe Asher A Used 911 in Perspective..............................6 Vice President—Rita Hancock Paradise Found . In the Fingerlakes! ............8 Secretary—Ann Marie von Esse Riesentöter’s Watkins Glen Event a Resounding Success ....................................10 Treasurer—Chris Barone Porsche Rennsport Reunion IV Attracts Membership Chair—Paula Gavin Famous Men and Machines ..........................12 Success Story: 15 Years of The Porsche Technical Chair—Larry Herman Mid-Engine Model Line .................................14 Social Chair—Wendy Walton Back to the Future – Prof. Ferdinand Porsche Created The First Functional Hybrid Car ........15 Autocross Chair—At Large Porsche Cars North America Launches Webmaster—Todd Little Silent Seller Mobile Tag Program for Porsche Dealerships ...............................16 Goodie Store Proprietor —Francine Knochenhauer Track Chair—Paul Walsack Departments Der Gasser Editor—At Large Upcoming Social Events ...............................18 If you would like to nominate a Club member for one of these offices, you Marktplatz .................................................. 19 may do so at the Member Meeting in September. Look for details to follow on the Web site and e-mail blasts. -

Karl E. Ludvigsen Papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26

Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Miles Collier Collections Page 1 of 203 Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Title: Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Creator: Ludvigsen, Karl E. Call Number: Archival Collection 26 Quantity: 931 cubic feet (514 flat archival boxes, 98 clamshell boxes, 29 filing cabinets, 18 record center cartons, 15 glass plate boxes, 8 oversize boxes). Abstract: The Karl E. Ludvigsen papers 1905-2011 contain his extensive research files, photographs, and prints on a wide variety of automotive topics. The papers reflect the complexity and breadth of Ludvigsen’s work as an author, researcher, and consultant. Approximately 70,000 of his photographic negatives have been digitized and are available on the Revs Digital Library. Thousands of undigitized prints in several series are also available but the copyright of the prints is unclear for many of the images. Ludvigsen’s research files are divided into two series: Subjects and Marques, each focusing on technical aspects, and were clipped or copied from newspapers, trade publications, and manufacturer’s literature, but there are occasional blueprints and photographs. Some of the files include Ludvigsen’s consulting research and the records of his Ludvigsen Library. Scope and Content Note: The Karl E. Ludvigsen papers are organized into eight series. The series largely reflects Ludvigsen’s original filing structure for paper and photographic materials. Series 1. Subject Files [11 filing cabinets and 18 record center cartons] The Subject Files contain documents compiled by Ludvigsen on a wide variety of automotive topics, and are in general alphabetical order. -

Press Release 3 June 2020

Press release 3 June 2020 On the anniversary weekend of 13/14 June in the Porsche Museum: the winning car 917 KH Porsche achieved the first overall victory at Le Mans 50 years ago Stuttgart, Germany. A total of 19 overall victories, countless class successes and incredible emotions have linked Porsche with the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the world's largest and most traditional motorsport event, for more than six decades. On 14 June 1970, Porsche achieved its first overall victory there with the 580 hp 917 KH sports car. 50 years later, on the weekend of June 13 and 14, 2020, the Porsche Museum will present the original winning car in its exhibition. Ever since Porsche participated in this endurance classic for the first time in 1951 and took an immediate class victory with the 356 SL, this race has become indispensable for the sports car manufacturer. But it was a long way to the first big triumph. Until the late 1960s, Porsche skilfully played the role of underdog and successfully concentrated on the smaller displacement classes. So Porsche initiated a change in strategy in the late 1960s. In 1969 Porsche was only 75 metres or a good second short of victory in the closest Le Mans finish in history. But already in the preparation phase for the 1970 race much of what had been learned in the years before was incorporated: Gerard Larrousse and Willy Kauhsen in the Martini Porsche 917 LH, followed by Rudi Lins and Helmut Marko in the Porsche 908/02 took second and third places respectively, making it a triumph for Porsche. -

Press Release September 27, 2018

Press Release September 27, 2018 Clubsport race car with 700 hp at the anniversary of 70 Years of Porsche Sports Cars World premiere: Exclusive new edition of the Porsche 935 Stuttgart. Porsche has unveiled the new 935 on the occasion of the historic “Rennsport Reunion” motorsport event at Laguna Seca Raceway in California. The 515 kW (700 hp) racer featuring a body reminiscent of the legendary Porsche 935/78 will be produced in a limited number of 77 units. “This spectacular car is a birthday present from Porsche Motorsport to fans all over the world,” says Dr Frank-Steffen Walliser, Vice President Motorsport and GT Cars. “Because the car isn’t homologated, engineers and designers didn’t have to follow the usual rules and thus had freedom in the development.” The race car’s technology for clubsport events and private training on racetracks is based on the 911 GT2 RS high-performance sports car. Like its historic predecessor, most of the body has been replaced or supplemented by carbon-fibre composite parts (CFRP). With its streamlined extended rear, the 935 reaches a length of 4.87 metres. The width of the exclusive clubsport racer measures 2.03 metres. The spectacular aerodynamics is a completely new development and pays tribute to the Porsche 935/78 Le Mans race car, which fans dubbed “Moby Dick” due to its elon- gated shape, massive fairings and white base colour. The distinctive wheel arch air vents on the front fairings, which also feature on the GT3 Porsche 911 GT3 R customer vehicle, increase downforce at the front axle. -

Porsche Zentrum Baden-Baden

Porsche TimesAusgabe November/Dezember 2006 Porsche Zentrum Baden-Baden Vor 50 Jahren: Targa Florio Eventreport I: Kundenausfahrt Eventreport II: Porsche Golf Turnier 2006 Der Porsche 917 / 30 Spyder Skydriving. Chronik: Ferdinand Porsche Porsche Approved Die neuen Modelle Geschenkideen zu Weihnachten 911 Targa 4. Seite 2 Porsche Times · Ausgabe November/Dezember 2006 Inhalt Neues Porsche Museum. PZ Baden-Baden Special Seite 2 Neues Porsche Museum. Seite 3 Porsche Cayenne Sieg bei der Transsyberia. Neues Antriebszentrum in Weissach. PZ Baden-Baden Eventreport Seite 4 Vor 50 Jahren: erster Gesamtsieg für Porsche bei der Targa Florio. Das spektakulärste Bauprojekt der Neues von Porsche Porsche AG, das neue Porsche Museum Seite 5 Skydriving. Die neuen Modelle 911 Targa 4. am Stammsitz in Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen nimmt zügig Gestalt an. Auf einer Nutz- Seite 6 Das einzigartige Dachkonzept. fläche von rund 21.000 Quadratmetern Seite 7 Permanenter Allradantrieb und mehr. wird hier das gesamte Wissen zum Seite 8 Die exzellente Sicherheitsausstattung. Thema Porsche gebündelt. So wird das neue Museum in verschiedenen Themen- PZ Baden-Baden Angebot bereichen die historische und zeitgenössi- sche Geschichte und Philosophie des Seite 9 Eventreport I: Kundenausfahrt mit 53 Porsche. Unternehmens zeigen. Hauptthema wird Seite 10/11 Eventreport II: Porsche Golfturnier 2006. die Produktchronologie sein, wobei Individuelle Kundenbetreuung ist unser oberstes Gebot. gleichzeitig am Konzept des „rollenden Seite 12 Der Porsche 917/30 Spyder. Museums“ festgehalten wird. „Wir werden die 80 Fahrzeuge im neuen Museum Seite 13/14/15 Chronik: Ferdinand Porsche (1875 – 1951). regelmäßig mit anderen Renn- und Sport- Seite 16 Porsche Approved. wagen aus unserem Fundus austauschen“ Seite 17 Neues Porsche Motorsportzentrum Weissach.