The Shifting Focus in the Abortion Debate: Does the Humanity of the Unborn Matter Anymore?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

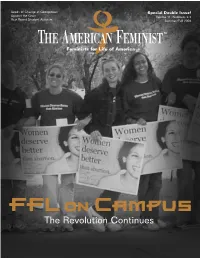

Summer-Fall 2004: FFL on Campus – the Revolution Continues

Seeds of Change at Georgetown Special Double Issue! Against the Grain Volume 11, Numbers 2-3 Year-Round Student Activism Summer/Fall 2004 Feminists for Life of America FFL on Campus The Revolution Continues ® “When a man steals to satisfy hunger, we may safely conclude that there is something wrong in society so when a woman destroys the life of her unborn child, it is an evidence that either by education or circumstances she has been greatly wronged.” Mattie Brinkerhoff, The Revolution, September 2, 1869 SUMMER - FALL 2004 CONTENTS ....... FFL on Campus The Revolution Continues 3 Revolution on Campus 28 The Feminist Case Against Abortion 2004 The history of FFL’s College Outreach Program Serrin Foster’s landmark speech updated 12 Seeds of Change at Georgetown 35 The Other Side How a fresh approach became an annual campus- Abortion advocates struggle to regain lost ground changing event 16 Year-Round Student Activism In Every Issue: A simple plan to transform your campus 38 Herstory 27 Voices of Women Who Mourn 20 Against the Grain 39 We Remember A day in the life of Serrin Foster The quarterly magazine of Feminists for Life of America Editor Cat Clark Editorial Board Nicole Callahan, Laura Ciampa, Elise Ehrhard, Valerie Meehan Schmalz, Maureen O’Connor, Molly Pannell Copy Editors Donna R. Foster, Linda Frommer, Melissa Hunter-Kilmer, Coleen MacKay Production Coordinator Cat Clark Creative Director Lisa Toscani Design/Layout Sally A. Winn Feminists for Life of America, 733 15th Street, NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20005; 202-737-3352; www.feministsforlife.org. President Serrin M. -

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: a Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov a Thesis

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: A Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science for honors Duke University Durham, North Carolina 2019 1 Note name change from National Front to National Rally in June 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to a number of people who were integral to my research and thesis-writing journey. I thank my advisor, Dr. Michael Munger, for his expertise and guidance. I am also very grateful to my two independent study advisors, Dr. Beth Holmgren from the Slavic and Eurasian Studies department and Dr. Michèle Longino from the Romance Studies department, for their continued support and guidance, especially in the first steps of my thesis-writing. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Heidi Madden for helping me navigate the research process and for spending a great deal of time talking through my thesis with me every step of the way, and to Dr. Richard Salsman, Dr. Genevieve Rousseliere, Dr. Anne Garréta, and Kristen Renberg for all of their advice and suggestions. None of the above, however, are responsible for the interpretations offered here, or any errors that remain. Thank you to the entire Duke Political Science department, including Suzanne Pierce and Liam Hysjulien, as well as the Duke Roman Studies department, including Kim Travlos, for their support and for providing me this opportunity in the first place. Finally, I am especially grateful to my Mom and Dad for inspiring me. Table of Contents 2 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………4 Part 1 …………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..5 Purpose ………………………………………………………………………………..13 Methodology and Terms ……………………………………………………………..16 Part 2 …………………………………………………………………………………………..18 The National Rally and Women ……………………………………………………..18 Marine Le Pen ………………………………………………………………………...26 Background ……………………………………………………………………26 Rise to Power and Takeover of National Rally ………………………….. -

Introducing Women's and Gender Studies: a Collection of Teaching

Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Teaching Resources Collection 1 Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Collection of Teaching Resources Edited by Elizabeth M. Curtis Fall 2007 Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Teaching Resources Collection 2 Copyright National Women's Studies Association 2007 Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Teaching Resources Collection 3 Table of Contents Introduction……………………..………………………………………………………..6 Lessons for Pre-K-12 Students……………………………...…………………….9 “I am the Hero of My Life Story” Art Project Kesa Kivel………………………………………………………….……..10 Undergraduate Introductory Women’s and Gender Studies Courses…….…15 Lecture Courses Introduction to Women’s Studies Jennifer Cognard-Black………………………………………………………….……..16 Introduction to Women’s Studies Maria Bevacqua……………………………………………………………………………23 Introduction to Women’s Studies Vivian May……………………………………………………………………………………34 Introduction to Women’s Studies Jeanette E. Riley……………………………………………………………………………...47 Perspectives on Women’s Studies Ann Burnett……………………………………………………………………………..55 Seminar Courses Introduction to Women’s Studies Lynda McBride………………………..62 Introduction to Women’s Studies Jocelyn Stitt…………………………….75 Introduction to Women’s Studies Srimati Basu……………………………………………………………...…………………86 Introduction to Women’s Studies Susanne Beechey……………………………………...…………………………………..92 Introduction to Women’s Studies Risa C. Whitson……………………105 Women: Images and Ideas Angela J. LaGrotteria…………………………………………………………………………118 The Dynamics of Race, Sex, and Class Rama Lohani Chase…………………………………………………………………………128 -

View / Open Strait Oregon 0171A 12876.Pdf

OCCUPYING A THIRD PLACE: PRO-LIFE FEMINISM, LEGIBLE POLITICS, AND THE EDGE OF WOMEN’S LIBERATION by LAURA STRAIT A DISSERTATION Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2020 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Laura Strait Title: Occupying a Third Place: Pro-Life Feminism, Legible Politics, and the Edge of Women's Liberation This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the School of Journalism and Communication by: Gretchen Soderlund Chairperson Carol Stabile Core Member Biswarup Sen Core Member Michael Allan Institutional Representative and Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2020 ii © 2020 Laura E Strait This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Laura Strait Doctor of Philosophy School of Journalism and Communication September 2020 Title: Occupying a Third Place: Pro-Life Feminism, Legible Politics, and the Edge of Women's Liberation This dissertation reads pro-life feminism as a break from traditional public perceptions of feminist thought. Through a variety of methodological analyses, it engages three case studies to answer (1) How does pro-life feminism persist as a movement and idea? And (2) What does the existence of pro-life feminists mean for the discursive boundaries of pro-choice feminism? This project included archival research on major feminist, anti-feminist, and pro-life feminist organizations, as well as long-form interviews with founding members of the pro-life feminist organizations. -

Representations of Feminism And

“The Bitch,” “The Ditz,” and the Male Heroes: Representations of Feminism and Postfeminism in Campaign 2008 by Dana Schowalter A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. Jane Jorgenson, Ph.D. Rachel Dubrofsky, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 17, 2009 Keywords: presidential coverage, women politicians, news media, politics, 2008 presidential election © Copyright 2009, Dana Schowalter To all the women who strive to be strong and independent, and especially to Helen Marie Schowalter, who encouraged me to do so. Acknowledgements First, and foremost, I would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Bell for her unending guidance, encouragement, and helpful comments, all of which have shaped this thesis into its current form. Without her, this project may never have been realized, and I cannot say enough about the ways she has helped me grow as a person, a writer, and a researcher. I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Rachel Dubrofsky and Dr. Jane Jorgenson, for their intellectual guidance and support throughout my career at the University of South Florida. Both encouraged me to continue my research on this topic by helping me focus on my passion for feminism and politics and not my frustration with the current system. I would also like to extend a special thank you to my family, who has been an unending source of love and support throughout this process. Though we may not always see eye to eye in our political discussions, your willingness to support me anyway in all my crazy ideas has made all the difference. -

A Chilling of Discourse

Saint Louis University Law Journal Volume 50 Number 2 A Tribute to the Honorable Michael A. Article 13 Wolff (Winter 2006) 2006 A Chilling of Discourse David Barnhizer Cleveland State University, Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David Barnhizer, A Chilling of Discourse, 50 St. Louis U. L.J. (2006). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj/vol50/iss2/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW A CHILLING OF DISCOURSE DAVID BARNHIZER* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 362 II. MULTICULTURALISM AND FRAGMENTATION ....................................... 365 III. LOSS OF OBJECTIVITY AND INTELLECTUAL INTEGRITY ....................... 370 IV. THE EFFECTS OF CHILLING ON THE INTEGRITY OF THE SCHOLAR .............................................................................................. 381 V. CHALLENGING “SOFT” REPRESSION ..................................................... 386 VI. CHILLING OF DISCOURSE THROUGH CONTROL OF ALLOWABLE SPEECH ............................................................................ 391 VII. CHILLING THROUGH INTOLERANCE AND THE SCHOLARSHIP OF RAGE ....................................................................... -

Abortion, Teen Pregnancy, and Feminism: Finding Women-Centric Solutions for Reproductive Justice

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-2016 Abortion, Teen Pregnancy, and Feminism: Finding Women-Centric Solutions for Reproductive Justice Jessica Faunce Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons Recommended Citation Faunce, Jessica, "Abortion, Teen Pregnancy, and Feminism: Finding Women-Centric Solutions for Reproductive Justice" (2016). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 983. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/983 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abortion, Teen Pregnancy, and Feminism: Finding Women-Centric Solutions for Reproductive Justice © Jessica Faunce, April 18, 2016 1 Abstract This two-part project seeks to understand, discuss, and address issues surrounding some of the most contentious debates in the United States: unplanned pregnancy and abortion. The first part of the project looks at the pro-life feminist movement’s agenda and ideals through comprehensive interviews with nine self-proclaimed pro-life feminists. The goal of this research is to gain an understanding of a women-centric opposition to abortion and to reflect on possible solutions that would benefit women and gain support from both pro-life and pro-choice advocates. Taking into account the information gathered through qualitative research on pro-life feminism, the second part of this project takes on the issue of teenage pregnancy in Onondaga County. -

Bystander Intervention: What If You Witnessed Some Form of Violence? What Would You Do? What Could You Do?

Many Voices Spring 2009 A newsletter of the University of St. Thomas Luann Dummer Center for Women, the University Committee on Women, and the Women’s Studies Program Women’s History Month Lecture WHY FEMINISM STILL MATTERS SUSAN FALUDI Tuesday, March 3, 2009 7 p.m. OEC Auditorium Reception/book signing following lecture A compelling voice in American feminism, writer Susan Faludi is one of the most astute chroniclers of the changing roles and expectations of men and women. After winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1991 as an investigative reporter for The Wall Street Journal, Faludi “set off firecrackers across the political landscape” (Time) with her groundbreaking book Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women. An eloquent examination of the issues facing women today, the book was an international best-seller and winner of the 1991 National Book Critics Circle Award. Considered a “groundbreaker” in terms of redefining gender perceptions, Susan’s thought provoking presentations challenge modern stereotypes and force people to re-evaluate their views and convictions in order to better understand and relate within the social structures of a modern society. Bystander Intervention: What if you witnessed some form of violence? What would you do? What could you do? A crucial element in the prevention of sexual violence is may be hanging out with a group of friends when one of them bystander intervention. We believe it is the responsibility of starts telling jokes about sexual assault, which may make you all people to intervene in situations where sexual violence may uncomfortable. You could intervene by talking about a occur and in situations where sexual violence is being different topic to draw the attention away from the jokes, or condoned. -

Amicus Brief

No. 19-1392 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- THOMAS E. DOBBS, STATE HEALTH OFFICER OF THE MISSISSIPPI DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, et al., Petitioners, v. JACKSON WOMEN’S HEALTH ORGANIZATION, et al., Respondents. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE FOR CONCERNED WOMEN FOR AMERICA IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- MARIO DIAZ Counsel of Record CONCERNED WOMEN FOR AMERICA 1000 N. Payne St. Alexandria, VA 22314 (202) 488-7000 [email protected] ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................. ii STATEMENT OF INTEREST ............................. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .............................. 2 ARGUMENT ........................................................ 4 I. Mississippi Should Be Free To Make Rea- sonable Determinations About Abortion Policy That Place A Higher Value On The Life Of Mothers And Their Unborn Chil- dren ............................................................ 4 II. -

Pro-Woman Framing in the Pro-Life Movement

Fighting for Life: Pro-Woman Framing in the Pro-life Movement Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alexa J. Trumpy Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Andrew Martin, Advisor Vincent Roscigno Liana Sayer Copyrighted by Alexa J. Trumpy 2011 Abstract How do marginal actors change hearts and minds? Social movement scholars have long recognized that institutional outsiders target a range of potential allies to press their agenda. While much of the movement research historically privileged formal political activities in explaining social change, understanding the way actors draw upon culture and identity to garner wider support for a variety of social, political, and economic causes has become increasingly important. Ultimately, research that incorporates political process theories with the seemingly dichotomous notions of cultural and collective identity is especially valuable. To better understand how movement actors achieve broad change, I draw on recent attempts to examine how change occurs in fields. I argue it is necessary to examine how a field’s structural and cultural components, as well as the more individual actions, resources, rhetoric, and ideologies of relevant actors, interact to affect field change or maintain stasis. This research does so through an analysis of the current debate over abortion in America, arguably the most viciously divisive religious, moral, political, and legal issue since slavery. Over the past four decades, the American abortion debate has been glibly characterized as fight between the rights of two groups: women and fetuses, with pro-choice groups championing the rights of the former and pro-life groups the latter. -

Activism 2000

Advocating for Women and Children Volume 7, Number 1 Women Who Died From Abortions Spring 2000 $5.00 Our Feminist History ACTIVISM2000 Feminists for Life proudly continues 200 years of pro-life feminism. SPRING 2000contents 3 Our Vision for a Better World 14 Real Power: Women and Philanthropy Woman-controlled dollars can accelerate institutional and Feminists for Life seeks basic human rights for all people. social change for the benefit of women and children. 18 Empower FFL The support of members is crucial as FFL continues to grow. 4 Live the Legacy Discover some of the ways you can show your support of Remembering all that our feminist foremothers achieved. women and children. 6 Activism 2000 20 E-Activism Pro-life feminists can help ensure that the next millennium FFL members can harness the power of the Internet to reach will be a springtime of hope through the development of millions with a message of hope and empowerment. sound public policy and promotion of change that benefits women and children in the workplace, at schools and at home. 22 The American Feminist: Providing a Voice The American Feminist fills a gap left by many feminist 8 Women and Men Making a Difference magazines. FFL activists put their talents to work in a variety of grassroots and advocacy areas—from campus student activism to program and policy implementation. 10 Supporting Women and Children in the Workplace In Every Issue: FFL members take on social ills that affect our nearest 23 College Outreach Program friends, families, neighbors and co-workers. FFL President Serrin Foster visits Washington University, University of California-Berkeley and University of Notre Dame. -

The Feminist Case Against Abortion,” Foster Redefines the Ideograph Of

REDEFINING <CHOICE>: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF “THE FEMINIST CASE AGAINST ABORTION” Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in Communication By Katie Bentley UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio August, 2013 REDEFINING <CHOICE>: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF “THE FEMINIST CASE AGAINST ABORTION” Name: Bentley, Katie Lynne Sparks APPROVED BY: Joseph Valenzano, III, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor Teri Thompson, Ph.D. Committee Member Jee Hee Han, Ph.D. Committee Member ii ABSTRACT REDEFINING <CHOICE>: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF “THE FEMINIST CASE AGAINST ABORTION” Name: Bentley, Katie Lynne Sparks University of Dayton Advisor: Joseph Valenzano, III In “The Feminist Case Against Abortion,” Foster redefines the ideograph of <choice> in a way that is both pro-woman and pro-life. She supports her definition with genetic and analogical arguments from the past. Her focus on <choice> makes her speech a unique voice in the larger abortion debate and avoids the stalemate caused by opposing sides that function under totally different value systems. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...iii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………1 Context ……………………………………………………………………………3 Text ……………………………………………………………………………...10 Methods ………………………………………………………………………….12 Conclusion and Outline of Chapters …………………………………………….13 CHAPTER 2: A BRIEF HISTORY OF ABORTION IN AMERICA ………………….14 Act I: Doctors, Feminists, and Abortion in Early America……………………...16