Pro-Woman Framing in the Pro-Life Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faden, Allie. “Abandoned Children and Surrogate Parental Figures.” Plaza: Dialogues in Language and Literature 5.2 (Summer 2015): 1-5

Faden, Allie. “Abandoned Children and Surrogate Parental Figures.” Plaza: Dialogues in Language and Literature 5.2 (Summer 2015): 1-5. PDF. Allie Faden Abandoned Children and Surrogate Parental Figures Abandonment, a common fear of children, has roots in literature due to a lengthy history of child abandonment in situations where parents feel the child would be better served away from its home. In our own culture, we see the literary roots of this motif as early as in Biblical writings, such as the story of Moses, continuing into the literature of today. In many instances children are abandoned not because they are unwanted, but out of parental hope that a life away from the natural parents will provide a “better” life for the child(ren). Societies have dealt with this concern in a multitude of ways over time, spanning from Church approval for poor parents to “donate” their child(ren) to the Church up to our modern system of criminalizing such actions (Burnstein 213-221, “Child Abandonment Law & Legal Definition”). During Puritan days, children were fostered out to other homes when a woman remarried after the death of her husband, and were often removed from the home if the parents failed to ensure access to education for the children (Mintz and Kellogg 4-17). Likewise, Scandinavian youths were frequently fostered to other families, either due to a lack of living children within a family, or to cement social bonds between people of varying social status (Short). In the British Isles, surrogate parentage was routine, involving child hostages, fostering to other families to cement social bonds, to deal with illegitimate births, or to encourage increased opportunities for children born to poor families (Slitt, Rossini, Nicholls and Mackey). -

A CASE for LEGAL ABORTION WATCH the Human Cost of Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Rights in Argentina

HUMAN RIGHTS A CASE FOR LEGAL ABORTION WATCH The Human Cost of Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Rights in Argentina A Case for Legal Abortion The Human Cost of Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Rights in Argentina Copyright © 2020 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-8462 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org AUGUST 2020 ISBN: 978-1-62313-8462 A Case for Legal Abortion The Human Cost of Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Rights in Argentina Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ........................................................................................................... 8 To the President of Argentina: ................................................................................................. -

Does Dental Fear in Children Predict Untreated Dental Caries? an Analytical Cross-Sectional Study

children Article Does Dental Fear in Children Predict Untreated Dental Caries? An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study Suman Panda 1 , Mir Faeq Ali Quadri 2,* , Imtinan H. Hadi 3, Rafaa M. Jably 3, Aisha M. Hamzi 3 and Mohammed A. Jafer 2 1 Division of Pediatric Dentistry, Department of Preventive Dental Sciences, Jazan University, Jazan 45142, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 2 Division of Dental Public Health, Department of Preventive Dental Sciences, Jazan University, Jazan 45142, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 3 Interns, College of Dentistry, Jazan University, Jazan 45142, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] (I.H.H.); [email protected] (R.M.J.); [email protected] (A.M.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Despite free health care services in Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of caries in children is substantially greater in comparison to other high-income countries. Dental fear in children may be an important issue that needs attention. Therefore, the aim was to investigate the role of dental fear in predicting untreated dental caries in schoolchildren. This analytical cross-sectional study included children aged 8–10 years residing in Saudi Arabia. Dental status via oral examinations was surveyed with the WHO standardized chart and the Children Fear Survey Schedule—Dental Subscale was used to score dental fear. Descriptive, binary, and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to report the findings at 5% statistical significance. Overall, there were 798 schoolchildren with an average fear score of 36. Nearly 70.4% reported fear of someone examining their mouth. About 76.9% had at least one carious tooth in their oral cavity. -

The Right to Remain Silent: Abortion and Compelled Physician Speech

Boston College Law Review Volume 62 Issue 6 Article 8 6-29-2021 The Right to Remain Silent: Abortion and Compelled Physician Speech J. Aidan Lang Boston College Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Health Law and Policy Commons, Litigation Commons, and the Medical Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation J. A. Lang, The Right to Remain Silent: Abortion and Compelled Physician Speech, 62 B.C. L. Rev. 2091 (2021), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol62/iss6/8 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RIGHT TO REMAIN SILENT: ABORTION AND COMPELLED PHYSICIAN SPEECH Abstract: Across the country, courts have confronted the question of whether laws requiring physicians to display ultrasound images of fetuses and describe the human features violate the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. On April 5, 2019, in EMW Women’s Surgical Center, P.S.C. v. Beshear, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit joined the Fifth Circuit and upheld Ken- tucky’s law, thus rejecting a physician’s free speech challenge. The Supreme Court declined to review this decision without providing an explanation. The Sixth Circuit became the third federal appellate court to rule on such regulations, often referred to as “ultrasound narration laws” or “display and describe laws,” and joined the Fifth Circuit in upholding such a law against a First Amendment challenge. -

Summary of Roe V. Wade and Other Key Abortion Cases

Summary of Roe v. Wade and Other Key Abortion Cases Roe v. Wade 410 U.S. 113 (1973) The central court decision that created current abortion law in the U.S. is Roe v. Wade. In this 1973 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that women had a constitutional right to abortion, and that this right was based on an implied right to personal privacy emanating from the Ninth and Fourteenth Amendments. In Roe v. Wade the Court said that a fetus is not a person but "potential life," and thus does not have constitutional rights of its own. The Court also set up a framework in which the woman's right to abortion and the state's right to protect potential life shift: during the first trimester of pregnancy, a woman's privacy right is strongest and the state may not regulate abortion for any reason; during the second trimester, the state may regulate abortion only to protect the health of the woman; during the third trimester, the state may regulate or prohibit abortion to promote its interest in the potential life of the fetus, except where abortion is necessary to preserve the woman's life or health. Doe v. Bolton 410 U.S. 179 (1973) Roe v. Wade was modified by another case decided the same day: Doe v. Bolton. In Doe v. Bolton the Court ruled that a woman's right to an abortion could not be limited by the state if abortion was sought for reasons of maternal health. The Court defined health as "all factors – physical, emotional, psychological, familial, and the woman's age – relevant to the well-being of the patient." This health exception expanded the right to abortion for any reason through all three trimesters of pregnancy. -

Children and Crime

© Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION 64340_ch01_5376.indd 20 7/27/09 3:36:37 PM © Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Nature and Extent of Delinquency 1 ection 1 introduces you to the problem of defining and measuring juvenile delinquency. Experts have struggled Sfor more than 100 years to define delinquency, yet it re- mains a complex problem that makes measurement even more difficult. CHAPTER 1 Chapter 1 reports on the status of children in American so- ciety. It also reviews past and present definitions of delinquency Defining Delinquency and defines legal definitions of delinquency that regulated the behavior of children in the American colonies, legal reforms inspired by the child-saving movement at the end of the nine- CHAPTER 2 teenth century, status offenses, and more recent changes in state and federal laws. Measuring Delinquency Chapter 2 examines the extent and nature of delinquency in an attempt to understand how much delinquency there is. Determining the amount and kind of delinquency acts that juve- niles commit, the characteristics of these acts, the neighborhoods these children live in, the kinds of social networks available, and the styles of lives they lead is vital to understanding where the problem of juvenile crime exists in U.S. society. Such knowl- edge also helps us to understand the problem more completely. Is delinquency only a problem of lower-class males who live in the inner city? Or does it also include females, middle-class children who attend quality schools, troubled children from good families, and “nice” children experimenting with drugs, alcohol, and sex? 64340_ch01_5376.indd 1 7/27/09 3:36:40 PM © Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. -

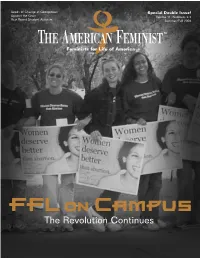

Summer-Fall 2004: FFL on Campus – the Revolution Continues

Seeds of Change at Georgetown Special Double Issue! Against the Grain Volume 11, Numbers 2-3 Year-Round Student Activism Summer/Fall 2004 Feminists for Life of America FFL on Campus The Revolution Continues ® “When a man steals to satisfy hunger, we may safely conclude that there is something wrong in society so when a woman destroys the life of her unborn child, it is an evidence that either by education or circumstances she has been greatly wronged.” Mattie Brinkerhoff, The Revolution, September 2, 1869 SUMMER - FALL 2004 CONTENTS ....... FFL on Campus The Revolution Continues 3 Revolution on Campus 28 The Feminist Case Against Abortion 2004 The history of FFL’s College Outreach Program Serrin Foster’s landmark speech updated 12 Seeds of Change at Georgetown 35 The Other Side How a fresh approach became an annual campus- Abortion advocates struggle to regain lost ground changing event 16 Year-Round Student Activism In Every Issue: A simple plan to transform your campus 38 Herstory 27 Voices of Women Who Mourn 20 Against the Grain 39 We Remember A day in the life of Serrin Foster The quarterly magazine of Feminists for Life of America Editor Cat Clark Editorial Board Nicole Callahan, Laura Ciampa, Elise Ehrhard, Valerie Meehan Schmalz, Maureen O’Connor, Molly Pannell Copy Editors Donna R. Foster, Linda Frommer, Melissa Hunter-Kilmer, Coleen MacKay Production Coordinator Cat Clark Creative Director Lisa Toscani Design/Layout Sally A. Winn Feminists for Life of America, 733 15th Street, NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20005; 202-737-3352; www.feministsforlife.org. President Serrin M. -

History of Legalization of Abortion in the United States of America in Political and Religious Context and Its Media Presentation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at University of West Bohemia Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce History of legalization of abortion in the United States of America in political and religious context and its media presentation Klára Čížková Plzeň 2017 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra románských jazyků Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor Cizí jazyky pro komerční praxi Kombinace angličtina – francouzština Bakalářská práce History of legalization of abortion in the United States of America in political and religious context and its media presentation Klára Čížková Vedoucí práce: Ing. BcA. Milan Kohout Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2017 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2017 ……………………… Na tomto místě bych ráda poděkovala vedoucímu bakalářské práce Ing. BcA. Milanu Kohoutovi za cenné rady a odbornou pomoc, které mi při zpracování poskytl. Dále bych ráda poděkovala svému partnerovi a své rodině za podporu a trpělivost. Plzeň, duben 2017 ……………………… Table of contents 1 Introduction........................................................................................................1 2 History of abortion.............................................................................................3 2.1 19th Century.......................................................................................................3 -

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: a Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov a Thesis

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: A Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science for honors Duke University Durham, North Carolina 2019 1 Note name change from National Front to National Rally in June 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to a number of people who were integral to my research and thesis-writing journey. I thank my advisor, Dr. Michael Munger, for his expertise and guidance. I am also very grateful to my two independent study advisors, Dr. Beth Holmgren from the Slavic and Eurasian Studies department and Dr. Michèle Longino from the Romance Studies department, for their continued support and guidance, especially in the first steps of my thesis-writing. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Heidi Madden for helping me navigate the research process and for spending a great deal of time talking through my thesis with me every step of the way, and to Dr. Richard Salsman, Dr. Genevieve Rousseliere, Dr. Anne Garréta, and Kristen Renberg for all of their advice and suggestions. None of the above, however, are responsible for the interpretations offered here, or any errors that remain. Thank you to the entire Duke Political Science department, including Suzanne Pierce and Liam Hysjulien, as well as the Duke Roman Studies department, including Kim Travlos, for their support and for providing me this opportunity in the first place. Finally, I am especially grateful to my Mom and Dad for inspiring me. Table of Contents 2 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………4 Part 1 …………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..5 Purpose ………………………………………………………………………………..13 Methodology and Terms ……………………………………………………………..16 Part 2 …………………………………………………………………………………………..18 The National Rally and Women ……………………………………………………..18 Marine Le Pen ………………………………………………………………………...26 Background ……………………………………………………………………26 Rise to Power and Takeover of National Rally ………………………….. -

1994Winter Vol3.Pdf

§ THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY IIVTER 1994 $3.95 ••* Jtg CANADA $4.50 a o THE 0 POLITICS 0 74470 78532 It adream: Is it an omen? _t Jit^ifciiTlity did everything they could to stop her from singing. Everything included threatening her, stalking her, slashing her and imprisoning her, on two continents. They wanted her to live as a traditional Berber woman. She had other plans. ADVENTURES IN AFROPEA 2: THE BEST OF Of silence HER BEST WORK. COMPILED BY DAVID BYRNE. On Luaka Bop Cassettes and Compact D.scs. Available in record stores, or direct by calling I. 800. 959. 4327 Ruth Frankenbera Larry Gross Lisa Bloom WHITE WOMEN, RACE MATTERS CONTESTED CLOSETS GENDER ON ICE The Social Construction of Whiteness The Politics and Ethics of Outing American Ideologies of Polar Expeditions "Frankenberg's impressive study of the "Combines a powerfully argued essay Bloom focuses on the conquest of the social geography of whiteness inaugu- with a comprehensive anthology of arti- North Pole as she reveals how popular rates a whole new, exciting, and neces- cles to create an invaluable document on print and visual media defined and sary direction in feminist studies: the 'outing.' Gross's fearless and fascinating shaped American national ideologies exploration of the categories of racial- book calls persuasively for ending a from the early twentieth century to the ized gender, and of genderized race in code of silence that has long served present. "Bloom's beautifully written the construction of white identity. ... An hyprocrisy and double-standard morality and incisively argued book works with a essential pedagogical and analytic text at the expense of truth." wealth of cultural artifacts and historical for 'the third Wave' of U.S. -

Interactions Between the Pro-Choice and Pro-Life Social Movements Outside the Abortion Clinic Sophie Deixel Vassar College

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2018 Whose body, whose choice: interactions between the pro-choice and pro-life social movements outside the abortion clinic Sophie Deixel Vassar College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Deixel, Sophie, "Whose body, whose choice: interactions between the pro-choice and pro-life social movements outside the abortion clinic" (2018). Senior Capstone Projects. 786. https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/786 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vassar College Whose Body, Whose Choice: Interactions Between the Pro-Choice and Pro-Life Social Movements Outside the Abortion Clinic A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Bachelor of Arts in Sociology By Sophie Deixel Thesis Advisors: Professor Bill Hoynes Professor Erendira Rueda May 2018 Deixel Whose Body Whose Choice: Interactions Between the Pro-Choice and Pro-Life Social Movements Outside the Abortion Clinic This project explores abortion discourse in the United States, looking specifically at the site of the abortion clinic as a space of interaction between the pro-choice and pro-life social movements. In order to access this space, I completed four months of participant observation in the fall of 2017 as a clinic escort at the Planned Parenthood clinic in Poughkeepsie, New York. I thus was able to witness (and participate in) firsthand the interactions between the clinic escorts and the anti-abortion protestors who picketed outside of the clinic each week. -

Family & Prolife News Briefs

Family & ProLife News Briefs October 2020 ProLifers Hopeful .... and Determined In the Culture In Public Policy 1. Many programs are expanding. For example, 1. Political party platforms are focusing more than 40 Days for Life is now active in hundreds of U.S. ever on life issues. The Libertarian platform states cities and is going on right now through Nov. 1st. life and abortion issues are strictly private matters. People stand vigil, praying outside of abortion The Democrat platform says “every woman should clinics. Also, the nationwide one-day Life Chain have access to ... safe and legal abortion.” The brings out thousands of people to give silent Republican platform states: “we assert the sanctity witness to our concern for a culture of life. And for of human life and ...the unborn child has a those who have taken part in an abortion, the fundamental right to life which cannot be infringed.” Church offers hope through Rachel’s Vineyard, a Respect life groups such as Priests for Life, & program of forgiveness and healing. the Susan B. Anthony List and others are seeking Another example: the Archdiocese of Miami’s election volunteers to get out the vote. Log onto Respect Life Ministry has been offering a monthly their websites if you might like to help. webinar as part of the U.S. Bishops theme of On Sept. 20th a full page ad in the NYTimes was "Walking with Moms: A Year of Service." Septem- signed by hundreds of Democrat leaders urging the ber’s webinar was How to Be a Pregnancy Center party to soften its stance towards abortion.