A Chilling of Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Public Eye, Fall 2002

TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL PublicEyeRESEARCH ASSOCIATES FALL 2002 • Volume XVI, No. 3 The Right Family Values The Christian Right’s “Defense of Marriage:” unpopular beliefs. Despite the First Amendment’s prohi- Democratic Rhetoric, Antidemocratic Politics bition against the establishment of religion by government, Christian conservatives By R. Claire Snyder cans oppose. While conservative Americans and their supporters often insist that Amer- are free to practice their beliefs and live their ica is really a “Christian nation.” They Introduction1 personal lives however they choose, the argue that the American founders believed government of the United States cannot he United States was founded as a that democratic political institutions would legitimately let those beliefs violate the “liberal democracy,” in which a secu- only work if grounded in religious mores T human rights of others in society. Similarly, lar government acts to protect the civil within civil society, emphasizing a comment it cannot generate public policy supporting rights and liberties of individuals rather made by John Adams: “Our Constitution a particular religious worldview or deny legal than imposing a particular vision of the was made only for a moral and religious peo- equality to certain groups of citizens. “good life” on its citizens. Equality before ple. It is wholly inadequate to the govern- the law constitutes one of the most funda- ment of any other.”9 William Bennett has mental principles of liberal democracy, as Liberal Democracy or Christian Nation? contributed greatly to this right-wing proj- does freedom from State-imposed religion. ect of revisionist historiography with the iberal political theory constitutes the These principles, enshrined in our found- publication of Our Sacred Honor: Words of ing documents, have become an almost Lmost important founding tradition of 5 Advice from the Founders, a volume that cat- universally accepted norm in U.S. -

A Humble Protest a Literary Generation's Quest for The

A HUMBLE PROTEST A LITERARY GENERATION’S QUEST FOR THE HEROIC SELF, 1917 – 1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason A. Powell, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Conn, Adviser Professor Paula Baker Professor David Steigerwald _____________________ Adviser Professor George Cotkin History Graduate Program Copyright by Jason Powell 2008 ABSTRACT Through the life and works of novelist John Dos Passos this project reexamines the inter-war cultural phenomenon that we call the Lost Generation. The Great War had destroyed traditional models of heroism for twenties intellectuals such as Ernest Hemingway, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos, compelling them to create a new understanding of what I call the “heroic self.” Through a modernist, experience based, epistemology these writers deemed that the relationship between the heroic individual and the world consisted of a dialectical tension between irony and romance. The ironic interpretation, the view that the world is an antagonistic force out to suppress individual vitality, drove these intellectuals to adopt the Freudian conception of heroism as a revolt against social oppression. The Lost Generation rebelled against these pernicious forces which they believed existed in the forms of militarism, patriotism, progressivism, and absolutism. The -

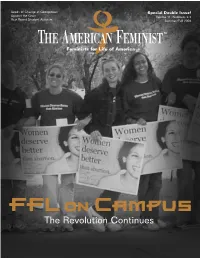

Summer-Fall 2004: FFL on Campus – the Revolution Continues

Seeds of Change at Georgetown Special Double Issue! Against the Grain Volume 11, Numbers 2-3 Year-Round Student Activism Summer/Fall 2004 Feminists for Life of America FFL on Campus The Revolution Continues ® “When a man steals to satisfy hunger, we may safely conclude that there is something wrong in society so when a woman destroys the life of her unborn child, it is an evidence that either by education or circumstances she has been greatly wronged.” Mattie Brinkerhoff, The Revolution, September 2, 1869 SUMMER - FALL 2004 CONTENTS ....... FFL on Campus The Revolution Continues 3 Revolution on Campus 28 The Feminist Case Against Abortion 2004 The history of FFL’s College Outreach Program Serrin Foster’s landmark speech updated 12 Seeds of Change at Georgetown 35 The Other Side How a fresh approach became an annual campus- Abortion advocates struggle to regain lost ground changing event 16 Year-Round Student Activism In Every Issue: A simple plan to transform your campus 38 Herstory 27 Voices of Women Who Mourn 20 Against the Grain 39 We Remember A day in the life of Serrin Foster The quarterly magazine of Feminists for Life of America Editor Cat Clark Editorial Board Nicole Callahan, Laura Ciampa, Elise Ehrhard, Valerie Meehan Schmalz, Maureen O’Connor, Molly Pannell Copy Editors Donna R. Foster, Linda Frommer, Melissa Hunter-Kilmer, Coleen MacKay Production Coordinator Cat Clark Creative Director Lisa Toscani Design/Layout Sally A. Winn Feminists for Life of America, 733 15th Street, NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20005; 202-737-3352; www.feministsforlife.org. President Serrin M. -

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: a Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov a Thesis

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: A Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science for honors Duke University Durham, North Carolina 2019 1 Note name change from National Front to National Rally in June 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to a number of people who were integral to my research and thesis-writing journey. I thank my advisor, Dr. Michael Munger, for his expertise and guidance. I am also very grateful to my two independent study advisors, Dr. Beth Holmgren from the Slavic and Eurasian Studies department and Dr. Michèle Longino from the Romance Studies department, for their continued support and guidance, especially in the first steps of my thesis-writing. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Heidi Madden for helping me navigate the research process and for spending a great deal of time talking through my thesis with me every step of the way, and to Dr. Richard Salsman, Dr. Genevieve Rousseliere, Dr. Anne Garréta, and Kristen Renberg for all of their advice and suggestions. None of the above, however, are responsible for the interpretations offered here, or any errors that remain. Thank you to the entire Duke Political Science department, including Suzanne Pierce and Liam Hysjulien, as well as the Duke Roman Studies department, including Kim Travlos, for their support and for providing me this opportunity in the first place. Finally, I am especially grateful to my Mom and Dad for inspiring me. Table of Contents 2 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………4 Part 1 …………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..5 Purpose ………………………………………………………………………………..13 Methodology and Terms ……………………………………………………………..16 Part 2 …………………………………………………………………………………………..18 The National Rally and Women ……………………………………………………..18 Marine Le Pen ………………………………………………………………………...26 Background ……………………………………………………………………26 Rise to Power and Takeover of National Rally ………………………….. -

A Feminist Epistemological Framework: Preventing Knowledge Distortions in Scientific Inquiry

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2019 A Feminist Epistemological Framework: Preventing Knowledge Distortions in Scientific Inquiry Karina Bucciarelli Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses Part of the Epistemology Commons, Feminist Philosophy Commons, and the Philosophy of Science Commons Recommended Citation Bucciarelli, Karina, "A Feminist Epistemological Framework: Preventing Knowledge Distortions in Scientific Inquiry" (2019). Scripps Senior Theses. 1365. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1365 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FEMINIST EPISTEMOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK: PREVENTING KNOWLEDGE DISTORTIONS IN SCIENTIFIC INQUIRY by KARINA MARTINS BUCCIARELLI SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR SUSAN CASTAGNETTO PROFESSOR RIMA BASU APRIL 26, 2019 Bucciarelli 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank my wonderful family for supporting me every step of the way. Mamãe e Papai, obrigada pelo amor e carinho, mil telefonemas, conversas e risadas. Obrigada por não só proporcionar essa educação incrível, mas também me dar um exemplo de como viver. Rafa, thanks for the jokes, the editing help and the spontaneous phone calls. Bela, thank you for the endless time you give to me, for your patience and for your support (even through WhatsApp audios). To my dear friends, thank you for the late study nights, the wild dance parties, the laughs and the endless support. -

Human-Computer Insurrection

Human-Computer Insurrection Notes on an Anarchist HCI Os Keyes∗ Josephine Hoy∗ Margaret Drouhard∗ University of Washington University of Washington University of Washington Seattle, WA, USA Seattle, WA, USA Seattle, WA, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 2019), May 4–9, 2019, Glasgow, Scotland, UK. ACM, New York, NY, The HCIcommunity has worked to expand and improve our USA, 13 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300569 consideration of the societal implications of our work and our corresponding responsibilities. Despite this increased 1 INTRODUCTION engagement, HCI continues to lack an explicitly articulated "You are ultimately—consciously or uncon- politic, which we argue re-inscribes and amplifies systemic sciously—salesmen for a delusive ballet in oppression. In this paper, we set out an explicit political vi- the ideas of democracy, equal opportunity sion of an HCI grounded in emancipatory autonomy—an an- and free enterprise among people who haven’t archist HCI, aimed at dismantling all oppressive systems by the possibility of profiting from these." [74] mandating suspicion of and a reckoning with imbalanced The last few decades have seen HCI take a turn to exam- distributions of power. We outline some of the principles ine the societal implications of our work: who is included and accountability mechanisms that constitute an anarchist [10, 68, 71, 79], what values it promotes or embodies [56, 57, HCI. We offer a potential framework for radically reorient- 129], and how we respond (or do not) to social shifts [93]. ing the field towards creating prefigurative counterpower—systems While this is politically-motivated work, HCI has tended to and spaces that exemplify the world we wish to see, as we avoid making our politics explicit [15, 89]. -

In the Decade Immediately Following the Second World War, Many Of

‘A Central Issue of Our Time’: Academic Freedom in Postwar American Thought A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Julian Tzara Nemeth August 2007 2 This thesis titled ‘A Central Issue of Our Time’: Academic Freedom in Postwar American Thought by JULIAN TZARA NEMETH has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Kevin Mattson Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract NEMETH, JULIAN TZARA., M.A, August 2007, History ‘A Central Issue of Our Time’: Academic Freedom in Postwar American Thought (108 pp.) Director of Thesis: Kevin Mattson In the early years of the Cold War, more than one hundred American academics lost their jobs because university administrators suspected them of Communist Party membership. How did intellectuals respond to this crisis? Referring to contemporary books, articles, organizational statements, and correspondence, I argue that disputes over academic freedom helped shatter a tenuous liberal consensus, unite conservatives, and challenge defenses of professorial liberty among academia’s largest professional organization, the American Association of University Professors. Specifically, I show how Sidney Hook and Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s dispute over academic freedom was representative of larger quarrels among liberals over McCarthyism. Conversely, I demonstrate that conservatives such as William Buckley Jr. and Russell Kirk overcame serious differences on academic freedom to present a united front against liberalism, in and outside of the academy. Finally, I show the difficulty an organization such as the AAUP encounters when defending professional values in a democratic society. -

Bradley Impact Fund

FROM THE DESK OF GABE CONGER BY THE NUMBERS Dear Friends, This month, nearly 1.9 million students will graduate with a bachelor’s degree. What will they take away from their college experience? Many will earn a STEM degree or gain experience through internships. Leadership and technology skills will be enhanced. Yet, too few will have greater respect for vigorous public dialogue and diversity of viewpoints. The pressure to conform to the political correctness so pervasive on America’s college campuses is a barrier to young Americans learning and valuing the principles of free speech and freedom of thought. These principles CLASS1.9M OF 2019 were essential to the founding of our nation, and they are just as essential today. BACHELOR'S DEGREES With such extensive uniformity of opinion, the "informed citizenry" of today is not what our founding fathers pictured. Our theme for this issue is the intersection of the power of ideas, education, and informed citizens. Robert P. George, Princeton University professor and Bradley Foundation Board Member, shares his perspective as a conservative academic 10:1 engaged with young Americans at the threshold of their independence. We’re DEMOCRAT also pleased to announce the 2019 Bradley Prizes winners, whose work has PROFESSORS steadfastly advanced an informed citizenry. The Grant Recipient Spotlight will OUTNUMBER help you create your summer reading list; and in The Future is Now, we share REPUBLICAN Lincoln Network co-founder Aaron Ginn’s ideas for collaboration of like-minded technologists using their Silicon Valley skills to advance liberty and viewpoint diversity. Free thought and free speech are under fire in our society. -

Greenp Eace.Org /Kochindustries

greenpeace.org/kochindustries Greenpeace is an independent campaigning organization that acts to expose global environmental problems and achieve solutions that are essential to a green and peaceful future. Published March 2010 by Greenpeace USA 702 H Street NW Suite 300 Washington, DC 20001 Tel/ 202.462.1177 Fax/ 202.462.4507 Printed on 100% PCW recycled paper book design by andrew fournier page 2 Table of Contents: Executive Summary pg. 6–8 Case Studies: How does Koch Industries Influence the Climate Debate? pg. 9–13 1. The Koch-funded “ClimateGate” Echo Chamber 2. Polar Bear Junk Science 3. The “Spanish Study” on Green Jobs 4. The “Danish Study” on Wind Power 5. Koch Organizations Instrumental in Dissemination of ACCF/NAM Claims What is Koch Industries? pg. 14–16 Company History and Background Record of Environmental Crimes and Violations The Koch Brothers pg. 17–18 Koch Climate Opposition Funding pg. 19–20 The Koch Web Sources of Data for Koch Foundation Grants The Foundations Claude R. Lambe Foundation Charles G. Koch Foundation David H. Koch Foundation Koch Foundations and Climate Denial pg. 21–28 Lobbying and Political Spending pg. 29–32 Federal Direct Lobbying Koch PAC Family and Individual Political Contributions Key Individuals in the Koch Web pg. 33 Sources pg. 34–43 Endnotes page 3 © illustration by Andrew Fournier/Greenpeace Mercatus Center Fraser Institute Americans for Prosperity Institute for Energy Research Institute for Humane Studies Frontiers of Freedom National Center for Policy Analysis Heritage Foundation American -

CHELSEA RECORD Thursday, March 4, 2021

YOUR HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER SINCE 1890 VOLUME 120, No. 49 THURSDAY, MARCH 4, 2021 35 CENTS APPRECIATION Long-time School Committee member Liz McBride dies at 100 By Cary Shuman Mrs. Elizabeth “Liz” McBride, who served on the Chelsea School Com- mittee for many years and was a member of the Chelsea Kiwanis Club, died on March 1. She was 100 years old. McBride was a beloved public figure and attended numerous events hosted by local organizations and Elizabeth “Liz” McBride. was warmly welcomed by all. She had incredible en- Looking out over Chelsea from the height of the clocks on the City Hall Tower, one can see Boston and beyond. The vista ergy and spread her good- from the tower is incredible, and this rare view is courtesy of the full restoration of the tower that has started and should will efforts throughout the be completed by June. dren, and passionate about community. bicycle safety – she was a Mrs. McBride was a pi- great woman and we will Officials begin restoration of City Hall Tower, dome oneer in the local Kiwanis miss her terribly.” Club, becoming its first Ramirez said the mem- By Seth Daniel righting the clock and become expensive and here, we’ve re-done that female member. Kiwanis bers will be paying trib- even applying a new lay- disruptive. The tower sits roof four times. That was President Sylvia Ramirez ute to Mrs. McBride at While a lot of Chelsea er of gilding to the Hall’s right above the Council’s the driving force of this lauded Mrs. -

The Proud Decades America in War and Peace, 1941-1960 1St Edition Download Free

THE PROUD DECADES AMERICA IN WAR AND PEACE, 1941-1960 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE John P Diggins | 9780393956566 | | | | | The Rise And Fall Of The American Left Diggins's interests ranged from the foundations of the United States to the postmodern world. Return to Book Page. Peter rated it it was amazing Jul 28, He was the author of more than a dozen books and thirty articles on widely varied subjects on American intellectual history. He earned a fellowship award from the Guggenheim Fellowship inbecame a resident scholar of the Rockefeller Foundation inand was nominated for the National book Award for History. To ask other readers questions about Ronald Reaganplease sign up. That was contrary to Diggins's personal experience of Reagan "standing for tear gas and police" [4] most likely in reference of the s Berkeley protests. Even if Reagan, like so many others, did The Proud Decades America in War and Peace fully envision exactly how communism would fall, he ended the cold war by creating what Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher insisted was the "essential trust" that would be necessary to allow the peaceful exit of the Soviet Union from history. Published February 17th by W. An obituary reported that Diggins "was "critical of the anticapitalist Left for seeing in the abolition of property an end to oppression" but also "critical of the antigovernment Right for seeing in the elimination of political 1941-1960 1st edition the end of tyranny and the restoration of liberty. Ask Seller a Question. Kristin-Leigh rated it did not like it Oct 02, Community Reviews. -

The Foundation of Feminist Research and Its Distinction from Traditional Research Joanne Ardovini-Brooker, Ph.D

Home | Business|Career | Workplace | Community | Money | International Advancing Women In Leadership Feminist Epistemology: The Foundation of Feminist Research and its Distinction from Traditional Research Joanne Ardovini-Brooker, Ph.D. ARDOVINI-BROOKER, SPRING, 2002 ...feminist epistemologies are the golden keys that unlock the door to feminist research. Once the door is unlocked, a better understanding of the distinctive nature of feminist research can occur. There are many questions surrounding feminist research. The most common question is: “What makes feminist research distinctive from traditional research within the Social Sciences?” In trying to answer this question, we need to examine feminist epistemology and the intertwining nature of epistemology, methodology (theory and analysis of how research should proceed), and methods (techniques for gathering data) utilized by feminist researchers. Feminist epistemology in contrast to traditional epistemologies is the foundation on which feminist methodology is built. In turn, the research that develops from this methodology differs greatly from research that develops from traditional methodology and epistemology. Therefore, I argue that one must have a general understanding of feminist epistemology and methodology before one can understand what makes this type of research unique. Such a foundation will assist us in our exploration of the realm of feminist research, while illuminating the differences between feminist and traditional research. An Introduction to Feminist Epistemology Epistemology is the study of knowledge and how it is that people come to know what they know (Johnson, 1995, p. 97). Originating from philosophy, epistemology comes to us from a number of disciplines, i.e.: sociology, psychology, political science, education, and women’s studies (Duran, 1991, p.